Apr 20, 2017 | News

Nepali authorities should immediately take effective steps to enforce the landmark Kavre district court murder verdict for the 2004 torture and killing of teenage Maina Sunuwar, the ICJ, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch said today.

On 16 April 2017, the Kavre district court sentenced three army officers to life imprisonment for the murder of Maina Sunuwar, a 15-year-old girl (photo) who was tortured in army custody and died as a result in February 2004.

Maina’s killing took place during the decade-long armed conflict between the Maoists and government forces that ended in 2006.

A court martial in 2005 found that Maina had died in army custody, convicted the three officers of torture and murder, but only sentenced the three perpetrators to six months’ imprisonment for minor offences, and promptly released them on grounds that they had already served the six months while confined to army barracks during the period of investigation.

“These convictions are an important development in Nepal’s slow-paced justice system’s ability to deal with grave conflict-era human rights abuses,” said Sam Zarifi, the ICJ’s Secretary General.

“What we need now is for the government to demonstrate its commitment to the rule of law and enforce them,” he added.

The trial before the Kavre district court took place in the absence of any of the four accused, despite repeated court summonses, including an arrest warrant, to notify them of the charges and compel them to appear in court.

The three accused army officers who were convicted of Maina Sunuwar’s murder, Bobi Khatri, Amit Pun and Sunil Adhikari, are no longer in the army and are believed to have fled abroad after the court martial proceedings.

The fourth accused, who was acquitted, Major Niranjan Basnet, is still in the army and was repatriated to Nepal from a UN peacekeeping assignment in Chad in 2009 due to the indictment against him.

Maina Sunuwar’s case has become emblematic of the shortcomings in Nepal’s justice system that have repeatedly frustrated efforts of Nepali conflict victims to secure justice for wartime abuses.

Maina Sunuwar’s mother first filed a report with the police in November 2005.

Since then, there have been numerous procedural and political hurdles, and a lack of cooperation by the military as it sought to protect its own.

An arrest warrant issued in 2008 was never enforced by Nepali authorities, with the police telling the court they were unable to trace them.

“Maina Sunuwar’s case was a true test case for the Nepal criminal justice system, but the government has a habit of simply ignoring court orders,” said Brad Adams, Asia director of Human Rights Watch. “This is the first sign of hope for victims after more than ten years since the end of the conflict—and now we need to see all those convicted of murder behind bars.”

The human rights organizations expressed concern that the government might refuse to seek to take measures to enforce the Kavre court’s verdict given its prior record on this and thousands of other conflict-era cases.

In a disturbing example, the police have yet to implement a 13 April 2017 Supreme Court order to arrest Bal Krishna Dhungel, a Maoist politician convicted of a 1998 murder.

Dhungel has yet to serve out his life sentence handed down by the courts.

The court gave the police a week to execute its order and present Dhungel before it.

“The Kavre district court has done its job, reaffirming the independence of the judiciary from political and military pressure, and holding perpetrators of serious crimes committed during the conflict to account,” said Biraj Patnaik, Amnesty International South Asia Regional Office Director. “Now the authorities must do their job by breaking with the practice of successive past governments that ignore and undermine the courts’ decisions. We expect the government to promptly implement this week’s ruling.”

Contact

Nikhil Narayan, ICJ’s South Asia Senior International Legal Adviser, e: Nikhil.narayan@icj.org

Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Secretery General, e: sam.zarifi@icj.org

Apr 13, 2017 | News

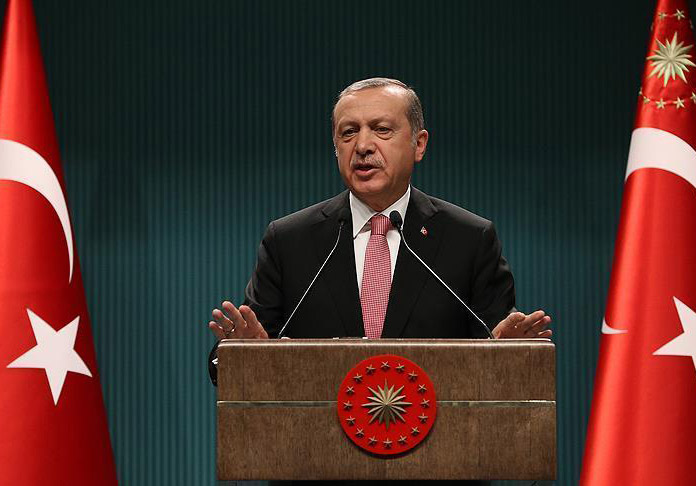

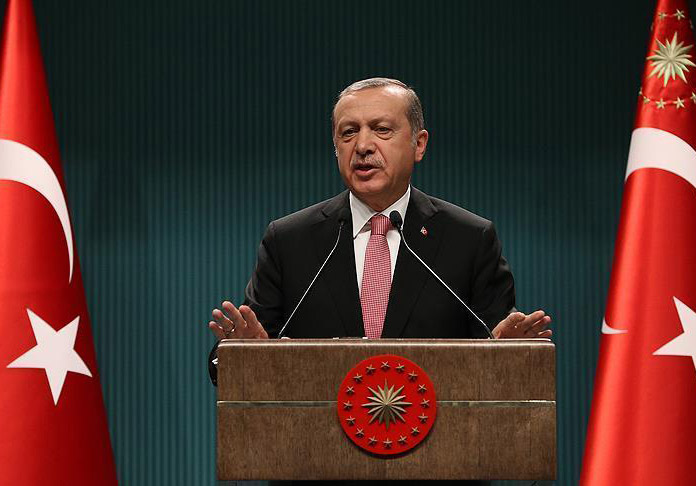

The ICJ today warned that proposed amendments to Turkey’s Constitution to be voted on in the referendum of 16 April could irremediably compromise the independence of the judiciary.

The amendments would introduce significant changes to the institutional framework governing the Turkish judiciary, with far reaching consequences for the separation of powers.

The ICJ is concerned that the proposed constitutional amendments, if approved, would enshrine in Turkish Constitution measures that would be severely damaging the rule of law in Turkey for the long term.

The separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary are fundamental components of the rule of law.

Under the proposals, the President of the Republic would be empowered to appoint six out of thirteen members of the High Council of Judges and Prosecutors, including four ordinary members as well as the Minister of Justice, (who would act as President of the Council) and the Under-Secretary of the Ministry of Justice.

The remaining seven members would be appointed by the National Assembly.

None of the members of the Council would be appointed by judges or public prosecutors.

The High Council of Judges and Prosecutors is the institution entrusted with the appointment, transfer, promotion, discipline and dismissal of judges and public prosecutors in Turkey.

It is the role of such a Council to act as a guardian of judicial independence and to protect the judiciary from interference by the executive and legislative powers.

The proposed Constitutional amendments are clearly contrary to international standards on the independence of the judiciary, which affirm that at least half of the members of a judicial council should be judges elected by their peers.

The amendments, if passed in the forthcoming referendum, would be enacted in a context where judicial independence has already been severely compromised.

Under the State of Emergency in place since the attempted coup of July 2016, approximately one fifth of the judiciary has been arbitrarily dismissed, and thousands of prosecutors and lawyers have been detained.

As the ICJ has previously highlighted, such measures have had a devastating effect on the independence of the judiciary at every level, compromising the courts’ ability to provide fair trials or an effective remedy for violations of human rights.

The ICJ understands that Turkey faced a serious threat to its democratic institutions in connection with the attempted coup of 15 July 2016.

Nonetheless, it stresses that measures meant to meet this threat must be undertaken within the framework of the rule of law and the country’s human rights obligations.

The ICJ reiterates its call on the Turkish authorities to lift the State of Emergency and the derogations from its international human rights law obligations that it has made as a matter of high priority.

Contact:

Róisín Pillay, ICJ Europe Programme Director, t: +32 2 734 84 46 ; e: roisin.pillay(a)icj.org

Background

An ICJ briefing paper of June 2016, the Turkey: the Judicial System in Peril , raised concern at measures eroding the independence of the judiciary, prosecution, and legal profession in Turkey, with serious consequences for protection of human rights.

The Council of Europe Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)12 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on judges: independence, efficiency and responsibilities, states:

- Not less than half the members of [councils for the judiciary] should be judges chosen by their peers from all levels of the judiciary and with respect for pluralism inside the judiciary.

Under international human rights law Turkey may derogate from certain human rights during a justified state of emergency only to the extent that derogating measures are strictly necessary to meet a current threat to the life of the nation.

Certain human rights, including freedom from torture, the right to life, and certain essential elements of the right to liberty, the right to a fair trial and the right to an effective remedy may never be restricted, even in an emergency situation.

Further guidance on relevant international law and standards can be found in the ICJ Legal Commentary to the Geneva Declaration on Upholding the Rule of Law and the Role of Judges and Lawyers in Times of Crisis.

Apr 12, 2017 | News

Saman Zia-Zarifi is the new Secretary General of the ICJ. He replaces Wilder Tayler who retired in March, the Geneva-based organization announced today.

An Iranian-American lawyer, Zarifi joined the ICJ in 2012 as Regional Director for the Asia & Pacific Region based in Bangkok, Thailand. Prior to joining the ICJ, he served as Amnesty International’s director for Asia and the Pacific from 2008 to 2012, and before that worked at Human Rights Watch from 2000.

“Wilder Tayler masterfully guided the ICJ for the past 10 years and expanded its reach across the world in perilous times,” said Prof Robert Goldman, the ICJ’s Acting President.

“The Commission is fully confident that Sam Zarifi will build on this legacy by bringing to the ICJ as a whole the energy and vision he deployed so successfully in the Asia Pacific region.”

The ICJ, founded in Berlin in 1952, is one of world’s oldest human rights organizations.

Composed of 60 accomplished jurists from all regions of the world, the ICJ has for 65 years devoted itself to promoting the observance of the rule of law and the legal protection of human rights.

The ICJ Secretary General leads the implementation of the Commission’s objectives through the ICJ’s International Secretariat.

The International Secretariat operates in locations around the world including Guatemala, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Tunisia, Belgium, Switzerland, Lebanon, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Myanmar, and Thailand.

“There is an urgent need to stand up against the recent attacks on the concept of rule of law and the international human rights legal framework that the ICJ was instrumental in building,” said Zarifi.

“We will challenge human rights violations and work with lawyers, judges and human rights defenders around the world to bring perpetrators to account and ensure victims receive justice,” he added.

The ICJ currently works globally and in all regions to protect human rights, defend the rule of law and strengthen the independence and accountability of judges and lawyers.

“Around the world, authoritarian rulers and demagogues are cynically using fearmongering and discriminatory language to justify erosion of the rule of law and weaken an independent judiciary,” Zarifi said.

“An increasing number of powerful politicians around the world attack international law when it suits them as a means of gaining more authority and hurting the most vulnerable segments of society.”

“The international legal framework has failed to address some very serious human rights crises and it has allowed gross economic inequalities to develop, but the answer is to fix the system and improve it, not just destroy it and allow the most powerful to rule without any legal restrictions,” Zarifi added.

The ICJ has been instrumental in developing many of the key universal and regional human rights legal standards, ranging from treaties on torture and enforced disappearances, the right to remedy and reparation, and most recently, seeking accountability for abuses by business entities.

It has provided both conceptual depth and practical advance to questions such as the justiciability of economic, social and cultural rights; human rights in states of emergency and other crises; and the fight against impunity.

“The ICJ’s experience over the past six decades has clearly shown that countries that respect the rule of law and protect human rights benefit from greater security and more sustainable economic development,” Zarifi said.

“There is greater demand than ever for the ICJ’s factual, law-based analysis of human rights problems and most important, how to improve the situation.”

Sam Zarifi was born and raised in Tehran, Iran. He moved to the United States in 1983 and completed a BA from Cornell University in 1990 and a Juris Doctor from Cornell Law School in 1993, and after a stint as a corporate litigator in Los Angeles, an Ll.M. in Public International Law from New York University School of Law in 1997.

He was Senior Research Fellow at Erasmus University Rotterdam from 1997 to 2000, where he co-edited Liability of Multinational Corporations under International Law (Kluwer 2000) as well as several other publications on the subject.

Contact

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Secretary General, t: +41 22 979 3825, c: +41 79 726 44 15 ; e: sam.zarifi@icj.org

Apr 10, 2017 | News

Zambia should reaffirm its membership in the International Criminal Court to best advance justice for victims of atrocities, a group of African organizations and international nongovernmental organizations – including the ICJ – with a presence in Africa said today.

Zambia’s government began public consultations on the country’s ICC membership the week of March 27, 2017.

This was in response to the African Union summit’s adoption in January of an “ICC withdrawal strategy.”

An unprecedented 16 countries, including Zambia, entered reservations to this decision.

Zambia has been a role model on the continent in matters of peace, democracy, and human rights. Leaving the ICC would erode the country’s leadership and threaten respect for the rights of victims of the most brutal crimes across Africa, the group of organizations said.

As a member of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), Zambia has a proud history in the establishment of the ICC, they added.

SADC was active in the diplomatic conference in Rome in 1998 where the ICC’s treaty was finalized after six weeks of negotiations.

SADC members developed 10 principles for an effective, independent, and impartial court at a meeting in Pretoria in 1997.

The ICC is a groundbreaking achievement in the fight against impunity, the organizations said.

It is the first and only global criminal court that can prosecute individuals responsible for atrocities.

It is a court of last resort in that it has the authority to try genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity committed since 2002, but only when national courts are unable or unwilling to investigate and prosecute.

Since the court’s treaty opened for signature in 1998, 124 countries have become members.

Zambia signed the ICC’s Rome treaty on July 17, 1998, the day it opened for signature, and ratified the treaty on November 13, 2000.

The ICC faces many challenges in meeting the expectations of victims of mass atrocities and member countries, the organizations said.

Its inability to reach crimes committed in some powerful countries and their allies is a cause for deep concern, even as claims that the ICC is targeting Africa are not supported by the facts.

The court’s reach is limited to crimes committed on the territories of countries that have joined the court or offered the court authority on its territory, absent a referral by the United Nations Security Council.

The majority of ICC investigations in Africa have arisen in response to requests or grants of authority by governments in the countries where the crimes were committed – as in Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, and Uganda – or through referrals by the UN Security Council – as in Darfur, Sudan and Libya.

The ICC has faced backlash from some African leaders since it issued arrest warrants for Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir for alleged genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity in Darfur in 2009 and 2010.

In 2016, evidence of the backlash reached new heights when South Africa, Burundi, and Gambia announced they would withdraw from the court, the first countries to take such action.

Gambia has rescinded its withdrawal and South Africa is also re-examining withdrawal, making Burundi the only country to have maintained its withdrawal.

Under the ICC Statute, withdrawal goes into effect one year after the state party submits a notification to the UN Secretary-General.

In the wake of the announced withdrawals, many African countries – including Botswana, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Lesotho, Mali, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Tunisia – have affirmed their commitment to remain in the ICC and to work for any reform as ICC members.

The organizations encourage Zambia to reaffirm its support for the court, particularly in the absence of any functioning regional criminal court that can hold perpetrators to account.

The groups expressing support for Zambia’s continued ICC membership are:

Africa Legal Aid

Africa Centre for International Law and Accountability–Ghana

Centre for Accountability and Rule of Law–Sierra Leone

Centre for Democratic Development–Ghana

Centre for Human Rights and Rehabilitation (Malawi)

Civil Resource Development and Documentation Centre (Nigeria)

Coalition for the International Criminal Court

Fédération Internationale des Droits de l’Homme

Human Rights Watch

Institute for Security Studies

International Commission of Jurists

JEYAX Development and Training (South Africa)

Kenya Section of the International Commission of Jurists

Kenya Human Rights Commission

Nigerian Coalition for the ICC

Parliamentarians for Global Action

Southern African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (Zambia)

Southern Africa Litigation Centre (South Africa)

Apr 6, 2017 | Адвокаси, Новости, Статьи, Юридические заявления

МКЮ вмешалась перед Европейским судом по правам человека по делу предполагаемого похищения таджикского гражданина и передачи его стране происхождения, где он может подвергаться риску пыток или жестокого обращения.

Международная комиссия юристов (МКЮ) вмешалась по делу К.Ф. против России. К.Ф. был подвергнут процедуре экстрадиции в Таджикистан для ответа на преступления, связанные с терроризмом. Процедура была приостановлена временными мерами, принятыми Европейским судом по правам человека по данному делу. В день его освобождения, по истечении максимального срока содержания под стражей, он исчез. Семья сообщила его адвокату, что он содержится в следственном изоляторе в Таджикистане.

В этом документе МКЮ предоставила Суду анализ, основанный на источниках международного права, позитивных обязательств участников Европейской конвенции обеспечить, чтобы передача лиц не осуществлялась, когда те лица находются под временным мерам Суда, запрещающим переводы. Представление включает сравнительный анализ права, юриспруденции и практики других региональных систем прав человека. МКЮ также оценила способность российской правовой системы защищать от передачи в нарушение прав Конвенции и, в частности, временных мер Суда.

МКЮ пришла к выводу, что российские власти еще не предоставили эффективную программу защиты, которая обеспечивала бы соблюдение временных мер Европейского суда в случаях предполагаемых похищений. Кроме того, МКЮ указала, что отсутствие каких-либо эффективных расследований и публичного осуждения практики похищения наносит ущерб эффективному осуществлению временных мер Суда.

МКЮ утверждала, что это продолжающееся отсутствие соблюдения российскими властями постановлений Европейского суда затрагивает всю систему соблюдения временных мер. Поэтому повторение этой ситуации требует разработки конкретных мер для повышения системных изменений в российском законодательстве и практике.

Russianfederation-KF_v_Russia-ECtHR-amicus-ICJ-final-eng-2017 (Скачайте вмешательство на английском)