Mar 30, 2021 | News

The ICJ today called for the reform of the country’s law on contempt of court to prevent their abuse and for the withdrawal of the contempt action filed against human rights lawyer Charles Hector.

Charles Hector faces potential contempt of court charges over a letter he sent to an officer of the Jerantut District Forest Office, as part of trial preparation. He is currently representing eight inhabitants of Kampung Baharu, a village in Jerantut, Pahang, in their civil lawsuit against two logging companies, Beijing Million Sdn Bhd and Rosah Timber & Trading Sdn Bhd.

The companies applied for leave to commence contempt of court proceedings against Charles Hector and the defendants. They claim that his letter violates an interlocutory injunction order prohibiting the villagers and their representatives from interfering with or causing nuisance to their work.

“Charles Hector is being harassed and intimidated through legal processes for carrying out his professional duties as a lawyer and gathering evidence in preparation for trial. The Malaysian authorities must act to protect human rights lawyers from sanctions and the threat of sanctions for the legitimate performance of their work,” said Ian Seiderman, the ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director.

The harassment of Charles Hector through legal processes violates international standards such as the UN Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers that make clear that lawyers must be able to perform their professional functions without intimidation, hindrance, harassment or improper interference.

Contempt of court, whether civil or criminal, may result in imprisonment and fines. Malaysia’s contempt of court offense is a common law doctrine and not codified statutorily.

“Fear of contempt charges stands to cast a chilling effect on the work of human rights lawyers and defenders. This further reinforces how Malaysia’s contempt of court doctrine needs to be urgently reformed as it is incompatible with international human rights law and standards,” said Seiderman.

The ICJ calls for the reform of Malaysia’s contempt of court doctrine to ensure clarity in definition, consistency in procedural rules and sentencing limits pertaining to criminal contempt cases. This reform should be in line with recommendations by the Malaysian Bar that the law of contempt be codified statutorily to provide clear and unequivocal parameters as to what really constitutes contempt.

Background

In September 2019, the two logging companies reportedly obtained approvals from the Jerantut District Forest Office to carry out logging in the Jerantut Tambahan Forest Reserve. The eight villagers are from a community many of whose residents have been protesting against the logging. The villagers depend on the forest reserve for clean water and their livelihoods.

On 14 July 2020, the companies filed a writ of summons against the eight villagers in the Kuantan High Court. The writ stated that the plaintiffs had applied for an injunction order to stop the defendants from preventing the companies’ workers from carrying out their works and spreading “false information” online.

On 5 November 2020, the companies successfully obtained an interlocutory injunction order. It was reported that the injunction order prohibits the defendants and their representatives from interfering with the approval given to the plaintiffs by the District Forest Office or causing nuisance to the work of the plaintiffs in any manner whatsoever, including physically, online or by communication with the authorities.

On 17 December 2020 Charles Hector sent a letter on behalf of his clients to Mohd Zarin Bin Ramlan, an officer of the Jerantut District Forestry Office, seeking clarifications on a letter sent by the office on 20 February 2020.

The logging firms contend that the letter violated the injunction order. In January 2021, the companies filed an ex parte application for leave to commence contempt of court proceedings against Charles Hector and the eight villagers.

The hearing was postponed until 25 March 2021 at the Kuantan High Court. On 25 March 2021, the plaintiff’s lawyer opposed the presence and participation of Charles Hector’s lawyer on the grounds that it was an ex parte application, which was contested by Charles Hector’s lawyer. The Court decided to adjourn the hearing to 6 April 2021.

Contact

Boram Jang, International Legal Adviser, e: boram.jang(a)icj.org

Mar 29, 2021 | Editorial, Incidencia, Noticias

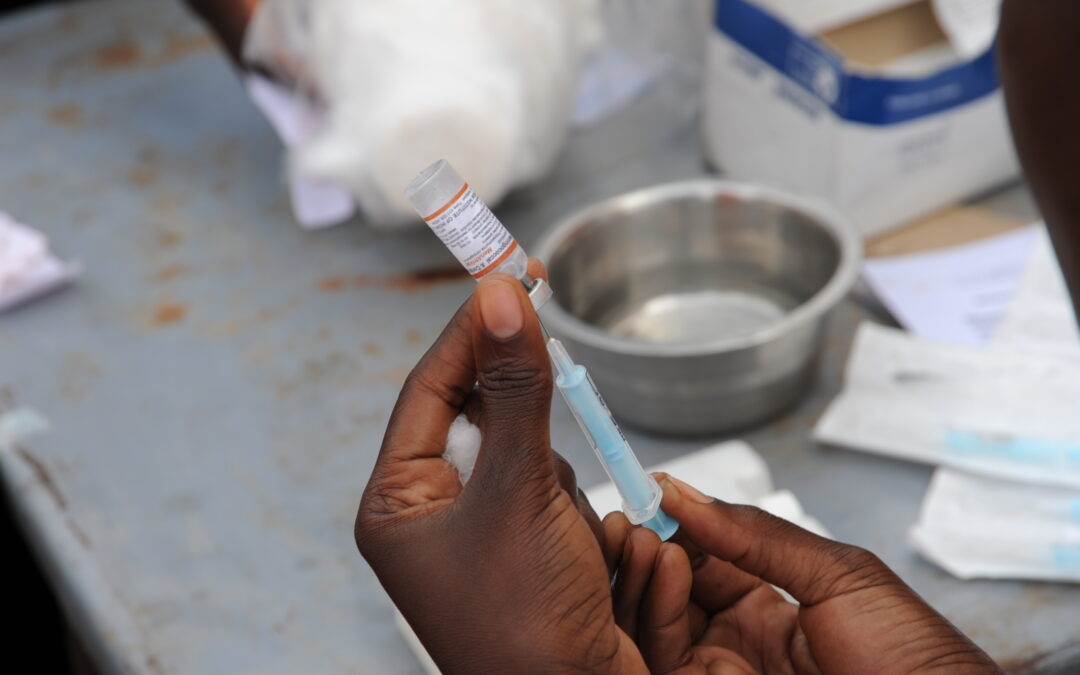

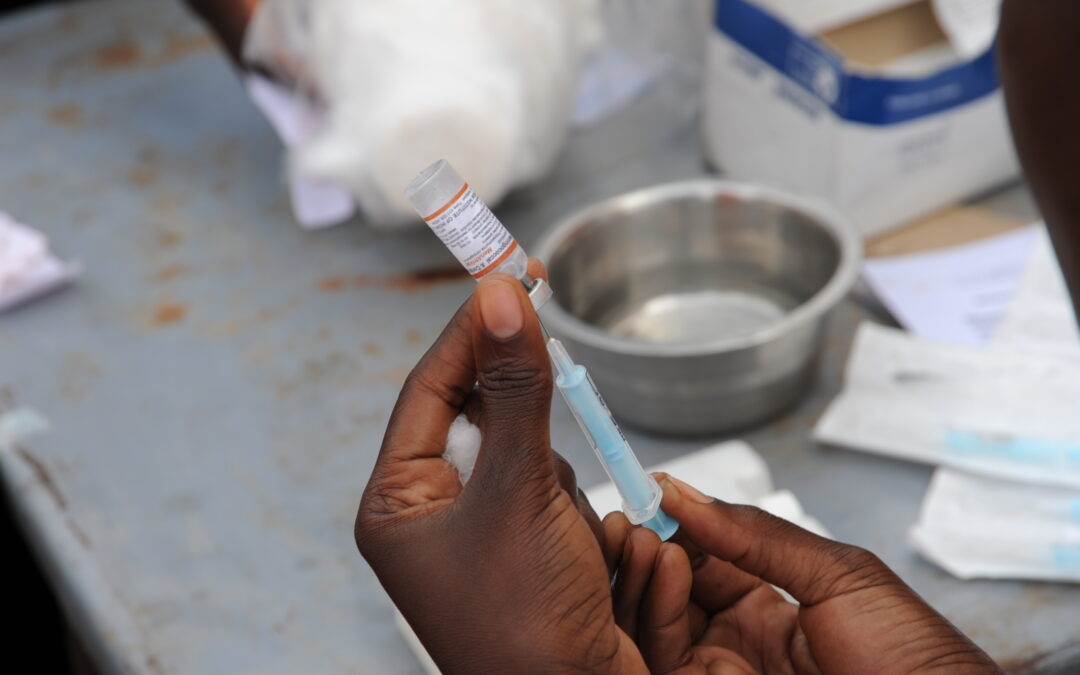

Por Tim Fish Hodgson (Asesor Legal en derechos económicos, sociales y culturales de la Comisión Internacional de Juristas) y Rossella De Falco (Oficial de Programa sobre el derecho a la salud de la Iniciativa Global para los Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales).

Históricamente, las pandemias han sido catalizadoras importantes de cambio social. En palabras del historiador sobre pandemias, Frank Snowden, “las pandemias son una categoría de enfermedad que parecen sostener un espejo en el que se puede ver quiénes somos los seres humanos en realidad”. Por el momento, mirarse en ese espejo sigue siendo una experiencia lamentablemente desagradable.

Los órganos de los tratados y los procedimientos especiales de las Naciones Unidas, la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS), el Programa Conjunto de las Naciones Unidas sobre el VIH/Sida (ONUSIDA) y numerosas organizaciones locales, regionales e internacionales de derechos humanos han producido múltiples declaraciones, resoluciones e informes que lamentan los impactos de la COVID-19 en los derechos humanos, en casi todos los aspectos de la vida, para casi todas las personas del mundo. El último documento relevante que se ha expedido sobre este tema es una resolución adoptada por el Consejo de Derechos Humanos. Esta resolución hace referencia a “Asegurar el acceso equitativo, asequible, oportuno y universal de todos los países a las vacunas para hacer frente a la pandemia de enfermedad por coronavirus (COVID-19)”. La resolución fue adoptada el 23 de marzo de 2021.

Entre las normas y estándares de derechos humanos que guían los análisis sobre los efectos de la COVID-19, se debe resaltar el derecho de toda persona al disfrute del más alto nivel posible de salud física y mental. Este derecho se encuentra consagrado en el artículo 12 del Pacto Internacional de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales (PIDESC), que tiene 171 Estados Parte. El derecho a la salud, en los términos que está consagrado en el PIDESC, impone a los Estados la obligación de tomar todas las medidas necesarias para garantizar “la prevención y el tratamiento de las enfermedades epidémicas, endémicas, profesionales y de otra índole”. Adicionalmente, respecto a el acceso a medicinas, el artículo 15 del PIDESC establece el derecho de todas las personas de “gozar de los beneficios del progreso científico y de sus aplicaciones”.

A pesar de estas obligaciones legales, a finales de febrero de 2021, el Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas, António Guterres, se sintió obligado a señalar el surgimiento de “una pandemia de violaciones y abusos a los derechos humanos a raíz de la COVID-19”, que incluye, pero se extiende más allá de las violaciones del derecho a la salud. El impacto de la COVID-19 en los derechos humanos ha, y continúa siendo, omnipresente. La gravedad de la situación ha sido perfectamente capturada en las palabras de la activista trans de Indonesia, Mama Yuli, quien al ser preguntada por una periodista sobre su situación y la de otros afirmó que era “como vivir como personas que mueren lentamente”.

Vacunas para unos pocos, pero ¿qué pasa con la mayoría?

Resulta decepcionante que, en lugar de ser un símbolo de esperanza de la luz al final del túnel de la pandemia, la vacuna de la COVID-19 se ha convertido rápidamente en otra clara ilustración de la pandemia paralela de violaciones y abusos a los derechos humanos, descrita por Guterres. El desastroso estado de la producción y distribución de la vacuna COVID-19 en todo el mundo – incluso dentro de países donde las vacunas ya están disponibles– es ahora a menudo descrito por muchos activistas, incluyendo de manera significativa la campaña de “Vacunas para la Gente” (People’s Vaccine campaign), como “nacionalismo de vacunas” y vacunas de lucro que ha producido un “apartheid de vacunas”.

Lo anterior significa, desde una perspectiva de derechos humanos, que los Estados a menudo han arreglado sus propios asuntos de una manera que es perjudicial para el acceso a las vacunas en otros países. Esto, a pesar de las obligaciones legales extraterritoriales de los Estados de, al menos, evitar acciones que previsiblemente resultarían en el menoscabo de los derechos humanos de las personas por fuera de sus territorios.

Es importante enfatizar que solo han pasado unos cuatro meses desde que comenzaron las primeras campañas de vacunación masiva en diciembre de 2020. Al momento en que este artículo se escribe, se habían vacunado aproximadamente 450 millones de personas en todo el mundo. No obstante, mientras que en muchas naciones africanas, por ejemplo, no han administrado una sola dosis, en América del Norte se han administrado 23 dosis de la vacuna COVID-19 por cada 100 personas. En el caso de Europa, la cifra es 13/100. La cifra disminuye drásticamente en el Sur global con 6.4/100 en América del Sur; 3.8/100 en Asia; 0.7/100 en Oceanía y apenas 0.6/100 en África.

Vacunas, obligaciones estatales y responsabilidades empresariales

La distribución inadecuada y desigual de las vacunas tiene diversas causas.

La primera causa es la naturaleza generalmente disfuncional del sistema de salud en todo el mundo. Lo cual se debe a, lo que el Comité de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales (Comité DESC), en su primera declaración sobre COVID-19 de abril de 2020, describió como “decenios de inversión insuficiente en los servicios de salud pública y otros programas sociales”. Las increíbles desigualdades causadas por la privatización de los servicios, instalaciones y bienes de salud, en ausencia de una regulación suficiente, están bien documentadas, tanto en el Norte Global como en el Sur Global.

La segunda causa son los obstáculos para acceder a la vacuna que han sido creados y mantenidos por los Estados, de manera individual o colectiva, a través de los regímenes de propiedad intelectual. Esto no se debe a la falta de lineamientos o mecanismos legales para garantizar la aplicación flexible de las protecciones de la propiedad intelectual a favor de la protección de la salud pública y la realización del derecho a la salud. Sobre este punto, en particular, hay que mencionar el Acuerdo sobre los Aspectos de los Derechos de Propiedad Intelectual relacionados con el Comercio (Acuerdo ADPIC o, en inglés, TRIPS agreement), un acuerdo legal internacional celebrado por miembros de la Organización Mundial del Comercio (OMC) que establece estándares mínimos para la protección de los derechos de propiedad intelectual.

Los Estados están explícitamente autorizados para interpretar las protecciones de los derechos de propiedad intelectual “a la luz del objeto y fin del” Acuerdo ADPIC. Por lo tanto, los Estados conservan el derecho de “conceder licencias obligatorias y la libertad de determinar las bases sobre las cuales se conceden tales licencias” en el contexto específico de emergencias de salud pública. Esta no es la primera vez que una epidemia ha requerido que se realicen acuerdos flexibles para garantizar un acceso rápido, universal, asequible y adecuado a medicamentos y vacunas vitales para salvar vidas.

Es por eso que, la gran mayoría de países y un número abrumador de actores de la sociedad civil han apoyado el requerimiento de Sudáfrica y de India para que la OMC emita una exención temporal (waiver) en la aplicación de los derechos de propiedad intelectual para “los diagnósticos, aspectos terapéuticos y vacunas” de la COVID-19. Este requerimiento ha sido formalmente apoyado por distintos expertos independientes de los procedimientos especiales del Consejo de Derechos Humanos. De igual manera, el 12 de marzo de 2021, a través de una declaración, el requerimiento recibió el respaldo enfático del Comité DESC. Adicionalmente, se debe mencionar que ya existen precedentes en la expedición de exenciones temporales sobre derechos de propiedad intelectual. Por ejemplo, la OMC ha aplicado una excepción temporal hasta 2033, para al menos los países menos desarrollados, que los exceptúa de aplicar las reglas de propiedad intelectual sobre productos farmacéuticos y datos clínicos.

Decepcionantemente, no se había secado la tinta de la declaración del Comité DESC, cuando, ignorando explícitamente todas estas recomendaciones, la excepción temporal fue bloqueada por una coalición de las naciones más ricas, muchas de las cuales ya tienen un acceso sustancial y avanzado a las vacunas. Es importante destacar que las recomendaciones del Comité DESC no se formularon por motivos políticos, sino como una manera de cumplir con la obligación establecida en el PIDESC de que “la producción y distribución de vacunas debe ser organizada y apoyada por la cooperación y la asistencia internacional”.

La reciente resolución del Consejo de Derechos Humanos, que fue liderada por Ecuador y el movimiento de Estados no alineados, brinda alguna esperanza de que se altere el actual curso de colisión hacia el desastre. La resolución, que pide el acceso a las vacunas sea “equitativo, asequible, oportuno y universal para todos los países”, reafirma el acceso a las vacunas como un derecho humano protegido y reconoce abiertamente la “asignación y distribución desigual entre países”.

La resolución procede a llamar a todos los Estados, individual y colectivamente, para que se “eliminen los obstáculos injustificados que restringen la exportación de las vacunas contra la COVID-19” y para que “faciliten el comercio, la adquisición, el acceso y la distribución de las vacunas contra la COVID-19” para todos.

Sin embargo, a pesar de las protestas de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil, que participaron en las deliberaciones sobre la resolución, esta solo reafirma el derecho de los Estados a utilizar las flexibilidades del Acuerdo ADPIC, en lugar de respaldar tales medidas como una buena práctica para cumplir las obligaciones de los Estados en materia de derechos humanos. En ese sentido, la resolución adopta un enfoque tibio, en tal vez, la cuestión más apremiante para garantizar el acceso a las vacunas. Este enfoque sigue los principios del comercio internacional, mientras que, irónicamente, ignora los estándares de derechos humanos, que debería considerar por ser una resolución emanada del Consejo de Derechos humanos. Como consecuencia, el enfoque de la resolución en la cuestión apremiante del Acuerdo ADPIC es inconsistente con la perspectiva de derechos humanos, que si tiene el resto de la resolución. Así las cosas, sorprendentemente, la resolución se queda corta y ni siquiera llega a insistir en que los Estados cumplan con sus obligaciones internacionales de derechos humanos establecidas desde hace mucho tiempo.

La resolución tampoco, inexplicablemente, aborda las responsabilidades corporativas, incluidas las de las empresas farmacéuticas, de respetar el derecho a la salud en términos de los Principios Rectores de las Naciones Unidas sobre Empresas y Derechos Humanos, así como el deber correspondiente de los Estados de proteger el derecho a la salud mediante la adopción de medidas regulatorias adecuadas.

La tercera causa, que se encuentra conecta a todo lo anterior, es el fracaso general de los Estados de cumplir de manera plena y adecuada sus obligaciones en materia de derechos humanos en el contexto de las respuestas que han dado a la pandemia de la COVID-19. La redacción sutil pero importante del ejercicio de las flexibilidades del Acuerdo ADPIC como un “derecho de los Estados”, en vez de una forma óptima de cumplir una obligación, expone que existe una asincronía. Específicamente, la manera en cómo los encargados de la formulación de políticas y los asesores jurídicos de los Estados ven y comprenden los derechos humanos, no se alinea con las obligaciones que tienen los Estados en materia de derechos humanos. Obligaciones que, por lo demás, los Estados han asumido de manera voluntaria al convertirse en parte de tratados como el PIDESC.

Un momento crítico: no tiene que ser de esta manera

Como predijo el perspicaz trabajo de Snowden, la pandemia de la COVID-19 representa un momento crítico en la historia de la humanidad. A los Estados, colectiva e individualmente, se les presenta una oportunidad única para sentar un precedente y comenzar a abordar seriamente las causas fundamentales de la desigualdad y la pobreza que prevalecen en todo el mundo.

Tomar la decisión correcta y adoptar una posición moral sobre la importancia del acceso a las vacunas COVID-19 es tanto práctica y simbólicamente importante para que estos esfuerzos tengan éxito. Las vacunas deben ser aceptadas y reconocidas como un bien mundial de salud pública y derechos humanos. Las empresas privadas tampoco deben obstaculizar el acceso equitativo y no discriminatorio a las vacunas para todas las personas.

Para que esto suceda, se requiere un liderazgo decidido de las instituciones internacionales de derechos humanos como el Consejo de Derechos Humanos, la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas y la OMC. Desafortunadamente, en la actualidad, no se ha hecho lo suficiente y la politiquería y el interés privado continúan prevaleciendo sobre los principios y el bien público. Hasta que esto cambie, muchas personas en todo el mundo seguirán existiendo, “viviendo como personas que mueren lentamente”. No tiene que ser de esta manera.

Mar 29, 2021 | Advocacy, News

On 25 March 2021, the ICJ filed two submissions to the UN Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) ahead of the review of Thailand’s human rights record in November 2021.

For this particular review cycle, the ICJ made two joint UPR submissions to the Human Rights Council.

In the joint submission by ICJ and Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR), the organizations provided information and analysis to assist the Working Group on the UPR to make recommendations addressing various human rights concerns that arise as a result of Thailand’s failure to guarantee, properly or at all, a number of civil and political rights, including with respect to:

- Constitution and Legal Framework: concerning the 2017 Constitution that continues to give effect to some repressive orders issued by the military junta after the 2014 coup d’état, the Emergency Decree, the Martial Law, and the Internal Security Act;

- Freedom of Expression and Assembly: concerning the use of laws that are not human rights compliant and, as such, arbitrarily restrict the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly, in the context of the Thai government’s response to the pro-democracy protests and, purportedly, to COVID-19; and

- Right to Life, Freedom from Torture and Enforced Disappearance: concerning the resumption of death penalty, the failure to undertake prompt, thorough and impartial investigations, and to ensure accountability of those responsible for the commission of torture, other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance, and the failure, to date, to enact domestic legislation criminalizing torture, other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance.

In the second, joint submission by ICJ, ENLAWTHAI Foundation and Land Watch Thai, the organizations provided information and analysis to assist the Working Group to make recommendations addressing various human rights concerns that arise as a result of Thailand’s failure to guarantee, properly or at all, a number of economic, social and cultural rights, including with respect to:

- Human Rights Defenders: concerning threats and other human rights violations against human rights defenders, and the restrictions on civil society space and on the ability to raise issues that the government deems as criticism of its conduct or that it otherwise disfavours;

- Constitution and Legal Framework: concerning the continuing detrimental impact of the legal framework imposed since the 2014 coup d’état on economic, social and cultural rights;

- Community Consultation: concerning the lack of participatory mechanisms and consultations, as well as limited access to information, for affected individuals and communities in the execution of economic activities that adversely impact local communities’ economic, social and cultural rights;

- Land and Housing: concerning issues relating to access to land and adequate housing, reports of large-scale evictions without appropriate procedural protections as required by international law, and the denial of the traditional rights of indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands and natural resources; and

- Environment: concerning the widespread and well-documented detrimental impacts of hazardous and industrial wastes on the environment, the lack of adequate legal protections for the right to health and the environment, and the effectiveness of the environmental impact assessment process set out under Thai laws.

The ICJ further called upon the Human Rights Council and the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review to recommend that Thailand should take various measures to immediately cease all aforementioned human rights violations; ensure adequate legal protection against such violations; ensure the rights to access to justice and effective remedies for victims of such violations; and ensure that steps be taken to prevent any future violations.

Download

UPR Submission 1 (PDF)

UPR Submission 2 (PDF)

Mar 28, 2021 | News

The credibility of the criminal trials currently ongoing before Tunisia’s Specialised Criminal Chambers depends on their capacity to deliver justice and reparation to victims and their families in a manner consistent with international law, said more than 25 Tunisian lawyers and human rights defenders at a workshop organized with the ICJ and international experts.

The workshop, which was held in Tunis on 25 and 26 March, aimed at enhancing the capacity of participants to use international law in the preparation and litigation of cases before the Specialized Criminal Chambers (SCC) effectively.

The participants discussed the application of international law and standards relating to the notions of victims and persons entitled to reparation before the SCC. Participants also considered the various forms of reparation, including restitution, compensation, rehabilitation and satisfaction, and guarantees of non–repetition.

The workshop was attended by international and Tunisian experts, along with ICJ representatives.

The Director of ICJ’s Middle East and North Africa Programme, Said Benarbia, emphasized the importance of guaranteeing the right of victims to effective remedies and reparations, especially in transitional justice contexts.

Mondher Cherni, the Secretary–General of the Tunisian Organization Against Torture (OCTT), underlined that reparations must be comprehensive. “Tunisian courts should ensure the adoption of a comprehensive notion of harm, while addressing the violations suffered by victims in Tunisia,” he said.

Rachel Towers, Legal Advisor at Dignity (The Danish Institute Against Torture)highlighted that there is no justice without remedies and reparations; accordingly, Tunisia should ensure that victims of gross human rights violations may enjoy these rights effectively.

Clive Baldwin, Senior Legal Advisor at Human Rights Watch, said that “Tunisia is not only bound to punish and sanction gross human rights violations, but also to prevent them from occurring in the future.” Baldwin also emphasized the importance of providing a comprehensive set of guarantees of non–repetition, including legislative and institutional reforms aiming to ensure effective civilian control of military and security forces and the independence of the judiciary.

Participants also addressed the lack of compliance in law and practice of the Tunisian transitional justice framework with international law and standards.

“The functioning and delivery of transitional justice in Tunisia has been enduring numerous and complex challenges over the last years,”said Benarbia.“The Tunisian authorities should immediately respond to these challenges with a holistic action plan, based on concrete reforms and solutions” Benarbia added.

Contact

Valentina Cadelo, Legal Adviser, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: valentina.cadelo(a)icj.org

Asser Khattab, Research and Communications’ Officer, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: asser.khattab(a)icj.org

Mar 26, 2021 | News

In a joint communication to five United Nations Special Procedures, the ICJ and its partners urged the mandate holders to call on the Tunisian authorities to immediately stop hampering the transitional justice process.

The organizations expressed their concern at the ongoing attempts to undermine the transitional justice process and accountability efforts for past gross human rights violations.

“The Tunisian transitional justice process has been under serious attack since its inception in 2013. Today, the ICJ and its partners are urging the United Nations Special Procedures to take urgent action to deter such attacks, demand justice for the victims and secure accountability for the perpetrators,” said the Director of ICJ’s Middle East and North Africa Programme, Said Benarbia.

The joint communication highlights the following areas of concern:

- The recent political initiatives to dismantle the transitional justice process;

- The incessant attacks against the Truth and Dignity Commission (Instance Verité et Dignité, IVD) and its 2018 final report’s findings;

- The lack of support to the Specialized Criminal Chambers (SCC) and the numerous obstacles that risk to severely impair access to justice and effective remedies for victims of gross human rights violations.

The communication is addressed to the following United Nations Special Procedures:

- The Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence;

- The Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment;

- The Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers;

- The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; and

- The Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances.

The communication was submitted jointly by the ICJ along with:

- The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

- The Ligue tunisienne des droits de l’homme (LTDH)

- The Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Economiques et Sociaux (FTDES)

- Avocats Sans Frontières (ASF)

- The Association of Tunisian Magistrates (AMT)

- Al Bawsla

- International Alert

- The Association KARAMA

- The Association INSAF pour les anciens militaires

- No Peace Without Justice

- The Organisation Contre la Torture en Tunisie (OCTT)

- The Organisation Dhekra we Wafa, pour le martyr de la liberté Nabil Barakati

- The Coalition Tunisienne pour la Dignité et la Réhabilitation

- The Association Tunisienne pour la Défense des Libertés Individuelles

- The Association des Femmes Tunisiennes pour la Recherche sur le Développement

- The Association Internationale pour le Soutien aux Prisonniers Politiques

- The Réseau tunisien de la justice transitionnelle

Contact

Valentina Cadelo, Legal Adviser, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: valentina.cadelo(a)icj.org

Asser Khattab, Research and Communications’ Officer, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: asser.khattab(a)icj.org

Download

Tunisia-Special-Procedures-Joint-Submission-2021 (PDF, in French)