Mar 23, 2021 | Advocacy, News, Op-eds

[TOC]By Tim Fish Hodgson, Legal Adviser on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights at the International Commission of Jurists and Rossella De Falco, Programme Officer on the Right to Health at Global Initiative on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Historically pandemics have often catalyzed significant social change. As historian of epidemics Frank Snowden puts it: “epidemics are a category of disease that seem to hold up the mirror to human beings as to who we really are”. At the moment gazing in that mirror remains a regrettably unpleasant experience.

United Nations human rights Treaty Body Mechanisms and Special Procedures, the World Health Organization (WHO), UNAIDS and numerous local, regional and international human rights organizations have produced reams of statements, resolutions and reports bemoaning the human right impacts of COVID-19 and almost every single aspect of the lives of almost all people around the world. The latest being the UN Human Rights Council Resolution adopted today by consensus on “Ensuring equitable, affordable, timely and universal access for all countries to vaccines in response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic”.

Key amongst the human rights law and standards underpinning these analyses is the protection of the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which, certainly for the 171 States Parties to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights places an obligation on States to take all necessary measures to ensure “the prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases”, and, in the context of access to medicines the right to “enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications”.

Despite these legal obligations, in late February, the UN Secretary General António Guterres felt compelled to highlight the rise of a “pandemic of human rights abuses in the wake of COVID-19”, including, but extending beyond violations of the right to health. The impact of COVID-19 on human rights has, and continues to be, sufficiently ubiquitous that an Indonesian transwoman activist Mama Yuli perhaps captured it best when telling a journalist that she and others in her position were “living like people who die slowly”.

Vaccines for the few, but what about the many?

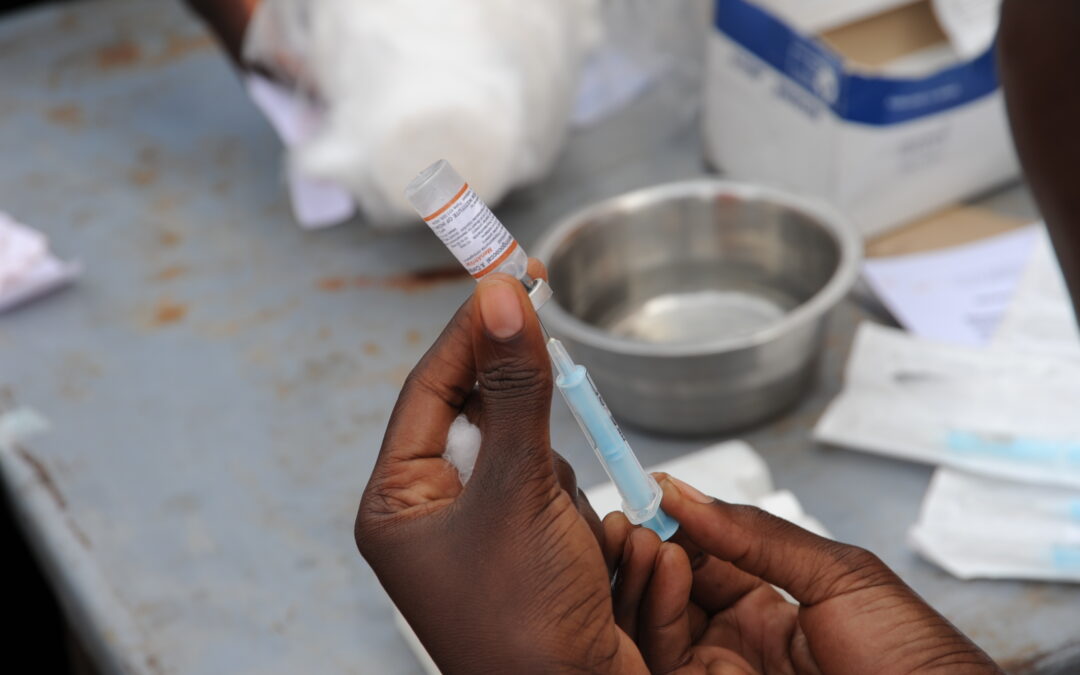

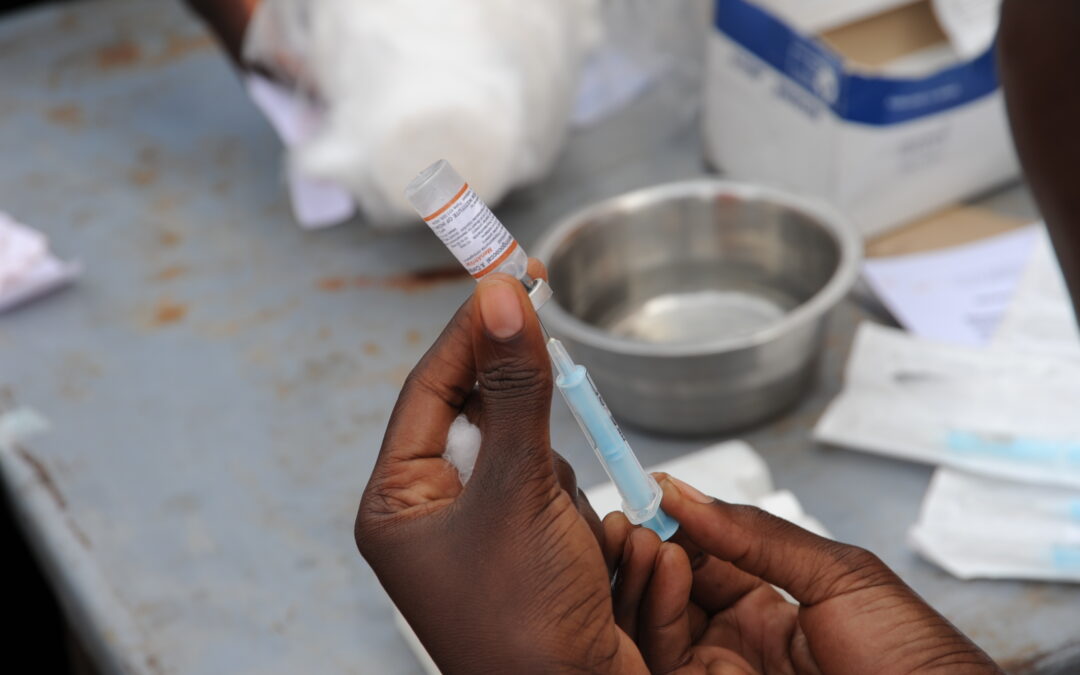

Disappointingly, however, instead of a symbol of hope of a light at the end of the Coronavirus tunnel, the COVID-19 vaccine has fast become yet another pronounced illustration of the parallel pandemic of human rights abuses described by Guterres. The disastrous state of COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution throughout the world – and even within particular countries where vaccines are available – is now often described by many activists, including significantly the People’s Vaccine campaign, as “vaccine nationalism” and profiteering which has produced a “vaccine apartheid”.

What this means, in human rights language, is that States have often arranged their own affairs in a way that is detrimental to access to vaccines in other countries in spite of their extraterritorial legal obligations to, at very least, avoid their actions that would foreseeably result in the impairment of the human rights of people outside their own territories.

It is worth emphasizing that it has still been only some four months since the first mass vaccination campaigns began in December 2020. At the time of writing, approximately 450 million people had been vaccinated worldwide, while many African nations, for example, had yet to administer a single dose. While in North America 23 COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered per 100 hundred people, with the number standing at 13/100 in Europe, the ratio decreases dramatically in the Global South with 6.4/100 in South America, 3.8/100 in Asia, 0.7/100 in Oceania and a mere 0.6/100 in Africa.

Vaccines, State Obligations and Corporate Responsibilities

The inadequate and inequitable distribution of vaccines has a variety of causes.

First, is the generally dysfunctional nature of the global health system due to what the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights described in its first statement on COVID-19 as early as April 2020 as “decades of underinvestment in public health services and other social programmes”. The incredible inequities caused by privatization of healthcare services, facilities and goods in the absence of sufficient regulation is well-documented, both in the Global North and the Global South.

Second, are the obstacles to vaccine access created and maintained by States, singly but collectively in the form of intellectual property rights regimes. This is not for a lack of guidance or legal mechanisms to ensure the flexible application of intellectual property protections in favour of the protection of public health and the realization of the right to health. The TRIPS agreement is an international legal agreement concluded by members of the World Trade Organization which sets minimum standards for intellectual property rights protections.

States are specifically permitted to interpret intellectual property rights protections “in the light of the object and purpose of” TRIPS and States therefore retain “the right to grant compulsory licences and the freedom to determine the grounds upon which such licences are granted” in the specific context of public health emergencies. Nor is it the first time that epidemics have necessitated the engagement of flexible arrangements to ensure expeditious, universal, affordable and adequate access to life saving medications and vaccines.

This is why the majority of States and an overwhelming majority of civil society actors have supported South Africa and India’s request that the WTO issue a “waiver” of the application of intellectual property rights for COVID-19 “diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines”. This request has also been formally supported by a number of independent experts of the UN Human Rights Council of UN Special Procedures, and recently received the emphatic endorsement of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. There is already precedent for such TRIPS waivers, with the WTO having already applied a waiver until 2033, for example, for least-developed countries (LDCs), which are exempted from applying intellectual property rules on pharmaceutical products and clinical data.

Disappointingly, however, the ink had barely dried on the issuing of the CESCR’s statement, when, plainly disregarding all of these recommendations, the waiver was blocked by a coalition of wealthier nations, many of whom already have substantial and advanced vaccine access. Importantly, the CESCR’s recommendations were not just made on vague policy grounds, but as the best way to fulfill States’ clear legal obligation in ICESCR that, “production and distribution of vaccines must be organized and supported by international cooperation and assistance”.

The recently adopted Resolution of the UN Human Rights Council, led by Ecuador and States of the Non-Aligned Movement and adopted on 23 March 2021 provides some hope of the alteration of this existing collision course with disaster. The resolution, which calls for “equitable, affordable, timely, and universal access by all countries”, reaffirms vaccine access as a protected human right and openly acknowledges “unequal allocation and distribution among countries”.

The resolution proceeds to call on all States, individually and collectively, to “remove unjustified obstacles restricting exports of COVID-19 vaccines” and to “facilitate the trade, acquisition, access and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines” for all.

However, despite the protestations of civil society organizations involved in deliberations about the resolution, the resolution only restates the right for States to utilize TRIPS flexibilities, as opposed to endorsing such measures as a best practice for realizing State human rights obligations. This tepid approach (which follows principles of international trade while, ironically given the resolution emanates from the Human Rights Council, ignoring human rights standards) to perhaps the pressing issue relating to vaccine access is inconsistent with the Resolution’s otherwise firm grounding of vaccine access in human rights. It therefore remarkably even falls short of insisting that States comply with their own long-established international human rights obligations.

The resolution also inexplicably fails to address corporate responsibilities, including those of pharmaceutical companies, to respect the right to health in terms of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and States’ corresponding duty to protect the right to health through adopting adequate regulatory measures.

Third, and connected to the above, is the general failure of States to fully and adequately centre their human rights obligations in the broader context of COVID-19 responses worldwide. The subtle but important phrasing of the exercise of TRIPS flexibilities as a “right of States” rather than as one of the optimal ways of fulfilling an obligation, exposes the degree to which the attitudes by State policy makers and legal advisors towards and understanding of human rights are out of sync with the obligations that they have willingly assumed by becoming party to treaties like the ICESCR.

A Critical Moment: it does not have to be this way

As Snowden’s insightful work predicted, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a critical moment in human history. States, collectively and individually, are presented with a unique opportunity to set a precedent and begin to seriously address the root causes of inequality and poverty which are prevalent across the world.

Making the right decision and taking a moral stand on the importance of access to COVID-19 vaccines is both practically and symbolically important if these efforts are to succeed. Vaccines must be accepted and acknowledged as global public health goods and human rights. Private companies too should not stand in the way of equitable and non-discriminatory vaccine access for all people.

For this to happen, bold leadership is required from international human rights institutions such as the UN Human Rights Council, the UN General Assembly and the WTO. Unfortunately, at present, not enough has been done and politicking and private interest continue to trump principle and public good. Until this changes, many people around the world will continue to exist, “living like people who are dying slowly”. It does not have to be this way.

Mar 19, 2021 | Advocacy, News

On 13 and 14 March 2021, the ICJ and the Association of Tunisian Magistrates (AMT) organized a roundtable discussion in Tunis to assist Specialized Criminal Chambers (SCC) judges and prosecutors to advance accountability and justice in line with international law and standards.

Participants discussed in-depth the ongoing challenges to the fair and effective prosecution and adjudication of gross human rights violations before the SCC. They also examined joint approaches to address these challenges with a view to enhancing the fairness and effectiveness of the SCC proceedings and achieving accountability in turn.

At the roundtable, Said Benarbia, ICJ’s MENA ProgrammeDirector, underlined that SCC trials should enable victims to obtain redress and reparation, while ensuring the defendants’ right to a fair trial in compliance with Tunisia’s obligations under international law. Anas Hmedi, the President of the AMT, highlighted the key role that the SCC play in relation to the discovery of the truth, accountability and guarantees of non-recurrence of gross human rights violations in Tunisia.

Martine Comte, ICJ France Commissioner,stressed the importance of finding joint approaches and reinforcing coordination among the SCC to address the various challenges that that they are currently facing. Kalthoum Kennou, ICJ Tunisia Commissioner, called for the development ofjoint approaches to ensure victims’ participation at SCC trials and enhance support for the transitional justice process.

In light of the roundtable discussion, participants identified joint solutions and agreed to develop a set of recommendations targeting the High Judicial Council and its role in supporting the SCC and resolving the practical obstacles that might impede their work.

The roundtable is part of the ICJ’s efforts to enhance the SCC’s capacity to adjudicate the cases referred to them by the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD) in a manner consistent with international law and standards.

Contact

Valentina Cadelo, Legal Adviser, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: valentina.cadelo(a)icj.org

Asser Khattab, Research and Communications’ Officer, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: asser.khattab(a)icj.org

Mar 18, 2021 | News

The ICJ today condemned Sri Lanka’s new ‘de-radicalization’ regulations, which allow for the arbitrary administrative detention of people for up to two years without trial. The regulations could disproportionately target minority religious and ethnic communities.

Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa promulgated Prevention of Terrorism (De-radicalization from holding violent extremist religious ideology) Regulations No. 01 of 2021, which was publicized by way of gazette notification on 12 March, 2021. The “regulations”, which were dictated by the executive without the engagement of Parliament, would send individuals suspected of using words or signs to cause acts of “religious, racial or communal violence, disharmony or feelings of ill will” between communities to be “rehabilitated” at “reintegration centres” for up to two years without trial.

“These regulations, which have been dictated by executive fiat, allow for effective imprisonment of people without trial and so are in blatant violation of Sri Lanka’s international legal obligations and Sri Lanka’s own constitutional guarantees under Article 13 of the Sri Lankan Constitution.”

– Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director

Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Sri Lanka is a party, provides for a number of procedural guarantees for any person deprived of their liberty, many of which are absent in the Regulation. Administrative detention of the kind contemplated under the Regulations, is not permitted, as affirmed repeatedly by the UN Human Rights Committee.

Even prior to the promulgation of the new regulations under Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act No. 48 of 1979 (PTA), Sri Lankan authorities had already been invoking the PTA and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Act, No. 56 of 2007 (enacted to incorporate certain provisions of the ICCPR into domestic law) effectively to persecute people from minority communities. Yet little or no action has been taken by the authorities against those inciting hatred or violence against minorities.

“The new regulations are likely to be used as a bargaining tool where the option is given to a detainee to choose between a year or two spent in “rehabilitation” or detention and trial for an indeterminate period of time, instead of a fair trial on legitimate charges.”

– Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director

Contact

Osama Motiwala, Communications Officer – osama.motiwala@icj.org

Background

Section 3(1) of the ICCPR Act which prohibits advocacy of hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, violence or hostility has hitherto been misused to target members of minority communities. In April 2020, Ramzy Razeek, a retired government employee, was arrested for a Facebook post calling for an ideological ‘jihad’ against the policy of mandatory cremation of people who had died as a result of Covid-19. He was detained under the ICCPR Act for more than five months and finally released on bail due to medical reasons in September 2020.

In May 2020, Ahnaf Jazeem, a young Muslim poet, was arrested under the PTA in connection with a collection of poems he had published in the Tamil language, which were apparently misinterpreted by Sinhalese authorities to be read as containing extreme messages. Just last week, a few days after the promulgation of the new regulations, Ahnaf’s lawyers expressed alarm that both Ahnaf and his father were being pressured to make admissions that he had engaged in teaching ‘extremism’. The ICJ had previously raised concerns about the arbitrary arrest and prolonged detention of Human Rights lawyer Hejaaz Hizbullah. After being detained under the PTA for 10 months without being given reason for his arrest, he is now being tried for speech-related offences under the PTA and ICCPR Act.

The ICJ has consistently called for the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act, which has been used to arbitrarily detain suspects for months and often years without charge or trial, facilitating torture and other abuse. The ICJ reiterates its call for the repeal and replacement of this vague and overbroad anti-terror law and regulations brought under it, in line with Sri Lanka’s international obligations.

The new PTA regulations require those who surrender or are arrested on suspicion of using words or signs to cause acts of violence, disharmony or ill will between communities to be handed over to the nearest Police Station within 24 hours after which a report is to be submitted by the Police to the Defence Minister (the position is currently held by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa) to consider whether the suspect should be detained further. The regulations would also apply to those who had surrendered or been taken into custody under the PTA, the Prevention of Terrorism (Proscription of Extremist Organizations) Regulations No. 1 of 2019 and the Emergency (Miscellaneous Provisions and Powers) Regulation, No. 1 of 2019.

The Attorney General is given the power to decide if a suspect should be tried for a specific offence or be send to a rehabilitation centre as an alternative. If the decision is to rehabilitate, the suspect would be produced before a Magistrate with the written consent of the Attorney General. The Magistrate may thereafter order that the suspect be referred to a rehabilitation centre for a period not exceeding one year. Such period can be extended by a period of six months at a time up to one more year by the Minister upon the recommendation of the Commissioner-General for Rehabilitation. The regulations further state that the Commissioner–General should provide the detainee with psycho-social assistance and vocational and other training during the rehabilitation period to ensure reintegration into society. The regulations also provide that such detainee may with the permission of the officer in charge of the Centre be entitled to meet their parents, relations or guardian once every two weeks.

Mar 17, 2021 | News

Imposition of Martial Law in several areas of Myanmar subjects civilians to trial by military tribunals, a dangerous escalation of the military’s repression of peaceful protests, said the ICJ today.

“Use of martial law marks the return to the dark days of completely arbitrary military rule in Myanmar. It effectively removes all protections for protestors, leaving them at the mercy of unfair military tribunals.”

– Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s director of law and policy

On 14 March, the Myanmar military issued Martial Law Order 3/2021, covering a number of townships of different provinces in Myanmar. According to this order, military officials assume full authority from civilian officials, and civilians may be subjected to military tribunals for charges of 23 violations of the criminal code and other laws. The 23 crimes include many of the charges used most against peaceful protesters in the past month, including charges of ‘disrupting or hindering government employees and services’ and ‘spreading false news’ about the government, and ‘exciting disaffection towards the government.’

The Martial Law Order also assigns disproportionately severe sentences, including the death penalty and prison sentences with hard labor. Judgments of military tribunals are not subject to appeal, even if the death penalty is imposed.

“Martial law has been imposed in precisely the areas where the military have used unlawful and lethal force against peaceful protesters, and removes even the pretense of access to courts for the people whose rights have been violated systematically by the military, ” said Seiderman.

The ICJ’s detailed review of military courts has documented that they lack competence, independence and impartiality to prosecute civilians. International law provides that the jurisdiction of military tribunals must generally be restricted solely to specifically military offenses committed by military personnel.

“The military courts lack transparency, due process and judicial oversights. It leaves no possibility to appeal the sentences, including the death sentences that have been handed down by military generals, ” said Seiderman.

Since the military coup d’etat of February 1 and the declaration of a state of emergency, the military has enacted and amended legislation enabling ongoing gross human rights violations, including possible crimes against humanity. More than 200 people have been unlawfully killed, with 2,000 more injured as security forces have used excessive force to suppress peaceful protests.

Background

On 14 March, the military-appointed State Administration Council, in accordance with Article 419 of the Constitution, enacted Martial Law Order 1/2021, imposing martial law in a number of areas in Yangon. The affected areas were further expanded through two other orders issued on 15 March, Martial Law Order 2/2021 and 3/2021. These orders transfer all power to the Military Commander in those areas. All local administration bodies have been placed under martial law, effectively giving military full control of all judicial and administrative processes.

The Order 3/2021 in particular is divided into six main sections with the most concerning provisions in relation to the list of crimes to be heard by military tribunals, and the proscribed punishments.

Contact

Osama Motiwala, ICJ Asia-Pacific Communications Officer, e: osama.motiwala(a)icj.org

Mandira Sharma: ICJ Senior Legal Adviser, e: mandira.sharma(a)icj.org