Sep 1, 2017 | Feature articles, News

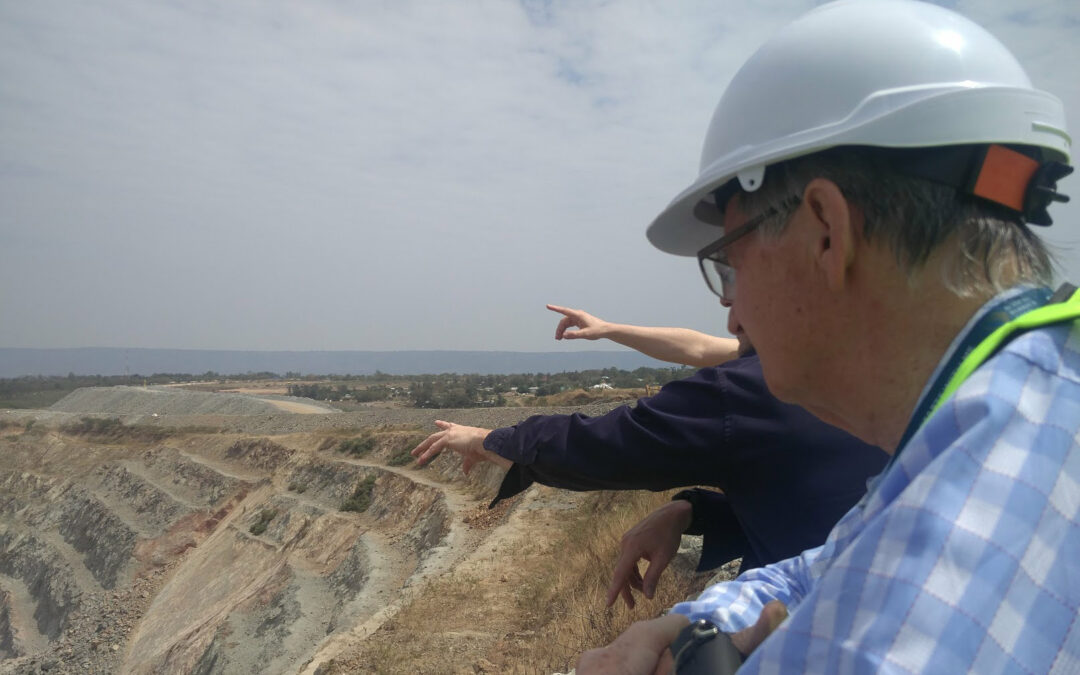

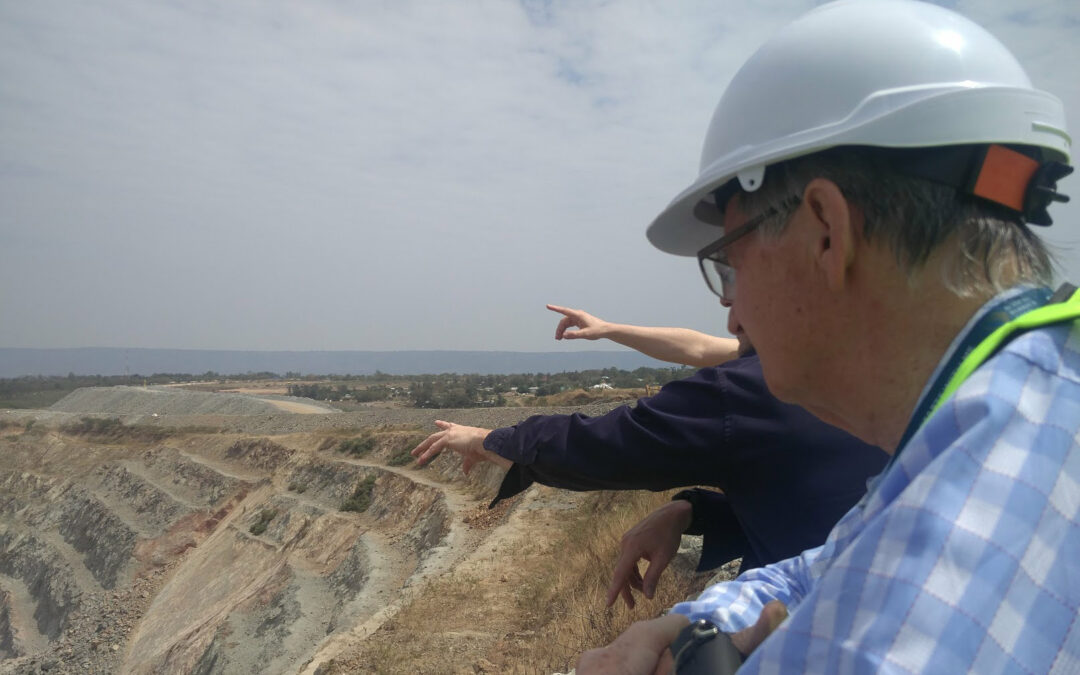

Today, an ICJ delegation concluded a learning and assessment mission to the North Mara region and the North Mara Gold Mine Ltd, a subsidiary of Acacia Mining plc located in north-west Tanzania in the Tarime district of the Mara region.

The visit took place between 27 August and 1 September.

The objective of the ICJ Mission was to learn about the operation with a view to assessing the effectiveness of the North Mara Gold Mine’s operational grievance mechanism (OGM) in addressing complaints over alleged human rights concerns and abuses committed in connection with the mine’s operations.

The members of the ICJ delegation were: ICJ Commissioners Justice Ian Binnie and Alejandro Salinas, accompanied by Mr Carlos Lopez, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser, and Mrs Antonella Angelini, researcher.

Read the full story here: Tanzania-BHR mission North Mara-News-Features article-2017-ENG (in PDF)

Sep 1, 2017 | News

Today the Supreme Court of Kenya took the unprecedented step of voiding the presidential elections held on 8 August 2017 citing the failure by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) to adhere to constitutionally mandated processes.

The ICJ commends the Supreme Court of Kenya for adjudication of a sensitive case at a high professional standards amidst a charged political atmosphere.

The ICJ in partnership with the Africa Judges and Jurists Forum (AJJF) sent a mission of three distinguished judges to observe the proceedings during the presidential petition in Kenya.

The delegation consisted of Retired Chief Justice Earnest Sakala (Zambia), Justice Dingake (Botswana) and Justice Chinhengo (Zimbabwe).

The mission’s observations will be publicized in due course.

Kenya held national elections on 8 August 2017 administered by the IEBC.

The IEBC subsequently announced that Uhuru Kenyatta had won the elections with a 54% majority.

The opposition National Super Alliance Coalition led by Raila Odinga filed an election petition alleging serious irregularities in the tabulation and transmission of the results of the elections and asking the court to nullify the results and order fresh elections.

The Supreme Court heard the election petitition culminating in the decision that was handed down today.

According to the observers, the court conducted the hearing in a manner consistent with the rule of law and that adhered to the Kenyan Constitution and international principles of a fair trial.

The Court gave acted fully as a competent, independent and impartial judicial body.

“The decision taken by the Supreme Court today is precedent setting. It places a cost on the election management body for apparently failing to adhere to constitutional imperatives and the normative framework governing the conduct of elections,” said Arnold Tsunga, Africa Director of the ICJ.

“Elections are a high stakes subject in Kenya, as elsewhere in the world. Previous elections have shown that violence and multiple human rights violations increase during the election period. We therefore encourage the political leaders in Kenya to accept the court’s verdict and to encourage their supporters to exercise maximum restraint and tolerance as the country braces itself for fresh elections,” he added.

Finally the ICJ urges the authorities in Kenya and the IEBC to quickly comply with and implement the court’s judgement.

Contact

Arnold Tsunga, ICJ Director for Africa, t: +27716405926 ; e: arnold.tsunga@icj.org

Sep 1, 2017 | News

On 1 September, the ICJ, in collaboration with Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Law and Chiang Mai University’s Center for Ethnic Studies and Development under its Faculty of Social Science, conducted a workshop on how effectively to conduct trial observation.

Participants in the Workshop included undergraduate and postgraduate students and lecturers from Chiang Mai University, lawyers and representatives from Thai civil society organizations.

The workshop was held at Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Law campus.

The objective of the workshop was to provide participants with an overview of international law and standards governing right to a fair trial and due process in the administration of criminal justice.

The workshop used the ICJ’s Practitioners Guide No. 5, the Trial Observation Manual for Criminal Proceedings, as the basis of training.

The workshop trained participants on practical preparation techniques before undertaking trial observations, critical elements of trial observations, drafting of trial observation reports, general international legal standards governing fair trials, international legal standards applicable to arrest and pre-trial detention in criminal proceedings and international legal standards applicable to trial proceedings.

The speakers at the workshop were Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser, Southeast Asia and Sanhawan Srisod, ICJ Associate National Legal Adviser, Thailand.

Aug 30, 2017 | News

On 30 August, the ICJ co-hosted an event in Bangkok, Thailand, named “International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearance: Human Rights Defenders & the Disappeared Justice”.

The event began with opening remarks by South-East Asia’s Regional Representative of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Cynthia Veliko.

Thereafter, Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser, spoke in a panel discussion about enforced disappearances in Thailand, highlighting the need for Thailand to comply with its human rights obligations under international law.

This panel discussion also included Ms. Oranuch Phonpinyo, Community Representative, forensics expert Dr. Pornthip Rojanasunan and former National Human Rights Commissioner Dr. Niran Pitakwatchara.

In a second panel discussion held during the event, speakers included Ms. Phinnapha Phrueksaphan, Victim Representative, Ms. Angkhana Neelapaijit, National Human Rights Commissioner and Victim Representative, Ms. Nareeluc Pairchaiyapoom from Thailand’s Ministry of Justice and prominent human rights lawyer Mr. Somchai Homlaor.

The event focused on the lack of progress in Thailand with regard to investigating cases of apparent enforced disappearance and called for the Royal Thai government to amend and pass legislation criminalizing torture, ill-treatment and enforced disappearance without further delay.

Thailand is a State party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) and has signed, but not yet ratified, the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED).

The other organizers of the event were OHCHR’s South-East Asia Regional Office, the Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF), Human Rights Lawyers Association (HRLA), the Esaan Land Reform Network, Amnesty International Thailand, Thailand’s Ministry of Justice and the Association for the Prevention of Torture (APT).

Copies of an open letter sent by the ICJ and other human rights groups to the Royal Thai government on 30 August were distributed to the event’s participants.

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

See the full open letter here in English and Thai

Read also

Ten Years Without Truth: Somchai Neelapaijit and Enforced Disappearances in Thailand

Aug 29, 2017 | News, Publications, Reports, Thematic reports

South Asian states can only address the tens of thousands of cases of enforced disappearances by recognizing enforced disappearance as a serious crime in domestic law, said the ICJ today.

On the eve of the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances, the ICJ 58-page report No more ‘missing persons’: the criminalization of enforced disappearance in South Asia analyzes States’ obligations to ensure that enforced disappearance constitutes a distinct, autonomous crime under national law.

It also provides an overview of the practice of enforced disappearance, focusing specifically on the status of the criminalization of the practice, in five South Asian countries: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal.

For each State, the report briefly examines the national context in which enforced disappearances are reported, the existing legal framework, the role of the courts; and the international commitments and responses to recommendations concerning criminalization.

“It is alarming that despite the region having some of the highest numbers of reported cases of disappearances in the world, enforced disappearance is not presently a distinct crime in any South Asian country,” said Frederick Rawski, ICJ’s Asia Director.

“This shows the lack of political will to hold perpetrators to account and complete apathy towards victims and their right to truth, justice and reparation,” he added.

In Nepal and Sri Lanka, draft legislation to criminalize enforced disappearance is under consideration.

Though the initiatives are welcome, the draft bills in both countries are flawed and require substantial improvements to meet international standards.

In the absence of a clear national legal framework specifically criminalizing enforced disappearance, unacknowledged detentions by law enforcement agencies are often treated by national authorities as “missing persons” cases.

On the rare occasions where criminal complaints are registered against alleged perpetrators, complainants are forced to categorize the crime as “abduction”, “kidnapping” or “unlawful confinement”.

These categories do not recognize the complexity and the particularly serious nature of enforced disappearance, and often do not provide for penalties commensurate to the gravity of the crime.

They also fail to recognize as victims relatives of the “disappeared” person and others suffering harm as a result of the enforced disappearance, as required under international law.

“Like torture and extrajudicial execution, enforced disappearance is a gross human rights violation and a crime under international law,” said Rawski.

“South Asian States must recognize that they have an obligation to criminalize the practice with penalties commensurate with the seriousness of the crime–filing “missing” person” complaints in cases of disappearance is not enough, and in fact, it trivializes the gravity of the crime,” he added.

Other barriers to bringing perpetrators to account are also similar across South Asian countries: military and intelligence agencies have extensive and unaccountable powers, including for arrest and detention, often in the name of “national security”; members of law enforcement and security forces enjoy broad legal immunities, shielding them from prosecution; and military courts have jurisdiction over crimes committed by members of the military, even where these crimes are human rights violations, and proceedings before such courts are compromised by their lack of independence and impartiality.

Victims’ groups, lawyers, and activists who work on enforced disappearance also face security risks including attacks, harassment, surveillance, and intimidation.

A comprehensive set of reforms, both in law and policy, is required to end the entrenched impunity for enforced disappearances in the region – criminalizing the practice would be a significant first step, said the ICJ.

Contacts:

Frederick Rawski (Bangkok), ICJ Asia Pacific Regional Director, e: frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

Reema Omer, ICJ International Legal Advisor (South Asia) t: +923214968434; e: reema.omer(a)icj.org

Thyagi Ruwanpathirana, ICJ National Legal Advisor (Sri Lanka), e: thyagi.ruwanpathirana(a)icj.org

Background

Under international law, an enforced disappearance is the arrest, abduction or detention by State agents, or by people acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the detention or by concealing the fate or whereabouts of the “disappeared” person which places the person outside the protection of the law.

The UN General Assembly has repeatedly described enforced disappearance as “an offence to human dignity”.

South Asia-Enforced Disappearance-Publications-Reports-Thematic Reports-2017-ENG (full report in PDF)