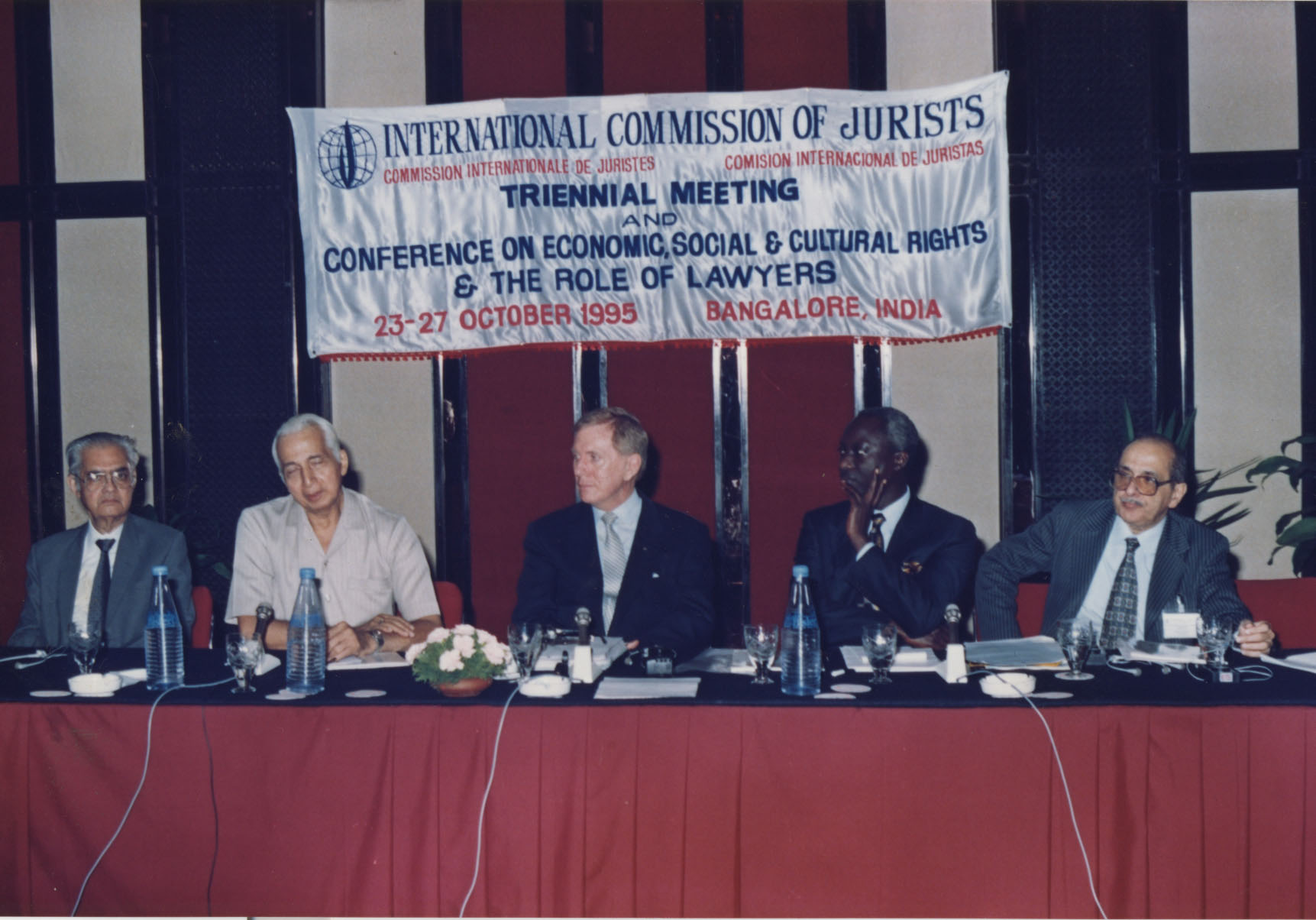

Between 23-25 October 1995, the ICJ, in conjunction with the Commission’s triennial meeting, convened in Bangalore, India, a conference on economic, social and cultural rights and the role of lawyers.

The Conference was inaugurated by the Chief Justice of India (The Honourable A.M. Ahmadi) and the Minister of State for External Affairs (The Honourable S. Kurseed, MP).

The Conference recalled the long-standing commitment of the ICJ to the indivisibility of human rights – economic, social, cultural, civil and political. That commitment has been evidenced over the years by the Declaration of Delhi 1959, the Law of Lagos 1961, the Limburg Principles on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1986, and the paper for the World Summit on Social Development 1995, amongst many other ICJ activities concerned with the promotion and protection of human rights for the attainment of the Rule of Law.

Reaffirming the Limburg Principles

The Conference reaffirmed the Limburg Principles. It considered regional perspectives on the realisation of economic, social and cultural rights. It examined the means of monitoring the attainment of such rights, including the observance of States’ obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). It considered the issues relating to the implementation and justiciability of those rights. It reviewed the steps which might be taken to achieve global endorsement of ICESCR in a way which promoted, at once, universal ratification of the Covenant and its genuine application as an influence upon the conduct of States and others.

The Conference reflected upon the need for an Optional Protocol to the ICESCR, to provide an individual and group complaint procedure similar to the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on ‘Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). This would provide a complaints mechanism to permit international monitoring of complaints of departures from the rights expressed in the ICESCR. In this regard, the Conference considered the several drafts for such a Protocol, including the 1994 draft prepared by the Chairperson of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the 1994 draft for CEDAW prepared in Maastricht and the 1995 draft prepared by a group of experts in Utrecht. The advantages of the several drafts were studied.

The role and responsibility of international financial institutions, in the promotion and protection of economic, social, and cultural rights were recognised. The recent concern about issues of economic, social and cultural rights on the part of the World Bank was welcomed.

The participants in the Conference reminded themselves that, in the words of the Limburg Principles :

- Economic, social and cultural rights are an integral part of international human rights law;

- The ICESCR is part of the International Bill of Rights;

- As human rights and fundamental freedoms are indivisible and interdependent, equal attention and urgent consideration should be given to the implementation, promotion and protection of economic, social and cultural rights as well as civil and political rights;

- The achievement of economic, social and cultural rights may be realised in a variety of political settings. There is no single road to their full attainment;

- Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), all sectors of society, Specialised Agencies and officers of the United Nations and individuals have an important part to play, in addition to the role of governments in attaining economic, social and cultural rights to their full measure.

- Trends in international and economic relations should be taken into account in assessing the efforts of the international community, to achieve the objectives of the ICESCR.

In particular, the participants noted that since the Limburg Principles were adopted, the centrally planned economies in a number of countries of Central and Eastern Europe and of Asia have collapsed. The economic arrangements of many countries had altered in ways which were then unpredictable.

The Conference recalled that the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna had reaffirmed the universality, interdependence and indivisibility of economic, social, cultural, civil and political rights and stressed the need for elaborating an Optional Protocol to the ICESCR aimed at establishing an international complaints system to monitor States compliance with their obligations in this field. By stressing both the human Right to Development and the importance of all human rights in achieving the goal of sustainable development, the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action made an important contribution to linking the human rights discourse with development.

The Conference recalled the reaffirmation by the United Nations World Summit on Social Development Copenhagen, 1995, of the universality, indivisibility, interdependence, and inter-relation of all human rights, including the right to development of people such that human rights, whether economic, social and cultural or civil and political, are a legitimate concern of the international community. The participants also recalled that the Copenhagen Summit’s Final Declaration encouraged the ratification and implementation by States of the ICESCR.

The Conference called attention to the acute disadvantages of women in the areas of economic, social and cultural rights and to the need for taking steps to overcome obstacles facing women’s full realisation of those rights. Jurists should co-operate with women and grass-roots organisations to formulate concrete measures to protect and promote economic, social and cultural rights of women, bearing in mind the Platform for Action adopted by the 1995 United Nations World Conference on Women held in Beijing.

Consideration was given to the extent, variety, and sometimes apparent incompatibility of reservations entered by States’ at the time of ratifying the ICESCR and other relevant treaties. The need for the development of a procedure for reviewing reservations or limiting their duration was discussed and supported. The Conference was reminded of the general principles of the law of treaties limiting the operation of incompatible reservations and of a recent general comment of the Committee on Human Rights that such reservations would be disregarded as inconsistent with the act of ratification.

Jurists’ Doubts and Neglect

Much time was devoted, as befitted a Conference of jurists, to examining the extent to which and means by which, in domestic jurisdiction the human rights recognised in ICESCR and other relevant international instruments are, or may become, justiciable. The Conference sought to analyse the reasons, often myths, why jurists had been less involved in the pursuit of the attainment of economic, social and cultural rights. Amongst other reasons, the participants identified and considered, the beliefs of some jurists that:

- Economic, social and cultural rights are not really rights of a legally enforceable kind;

- Such rights are variable in content, altering over time and resistant to precise legal enforcement;

- Such rights, however important, are not really the specific domain of lawyers;

- Such rights, for their attainment typically involve large expenditures of money and other resources the determination of which should better be left to government which is, or should be, accountable to the people rather than to the courts whose members may have neither expertise nor the information with which to make decisions having a large economic or social significance;

- Whilst realisation of civil and political rights have clear economic costs, the attainment of the “right to work”, “right to housing” and other economic, social and cultural rights is much more likely to involve large issues of social and political policy in which lawyers have a role to play as politicians and citizens but much lesser role to play as legal professionals. Several participants warned against the tendency of the law, its institutions and professionals, to overstretch their proper function and expertise and to “legalise” issues which are more properly decided in a context, and according to considerations, larger than typically found in courts of law.

The Conference acknowledged the foregoing concerns and opinions which, amongst others, help to explain the reluctance of jurists to become directly concerned in the realisation of economic, social and cultural rights by means of the techniques of the law and using the courts and other instruments of legal practice. The widespread ignorance of the ICESCR, not only amongst judges and lawyers but also amongst governments and in the community was a matter of concern.

The Conference however,

- reaffirmed the fact that economic, social and cultural rights are an essential part of the global mosaic of human rights;

- noted the important role of lawyers and judges in countries, such as India, in applying and judicially enforcing economic, social and cultural rights in the context of the right to life, fair trial, equality before the law, equal protection of the law and other civil and political rights;

- resolved that jurists in the future should play a greater part in the realisation of such rights, than they have in the past, without in any way diminishing the vital work of lawyers in the attainment of civil and political rights;

- affirmed that the realisation of economic, social and cultural rights is often of wider application and more pressing urgency, affecting every day, as such rights do, all members of society. For lawyers to exclude themselves from a proper and constructive role in the realisation of such rights would be to deny themselves a function in a vital area of human rights;

- The task of the Conference was, therefore, one of defining those activities in support of the realisation of these rights in which lawyers qua lawyers might have a legitimate and constructive function and to promote within the judiciary and the legal profession, in every land, a realisation of the opportunities and obligations which fall to lawyers in this regard.

The Conference affirmed that impunity of perpetrators of grave and systematic violations of economic, social and cultural rights, including corruption by State officials is an obstacle to the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights which must be combated.

An independent Judiciary is indispensable to the effective implementation of economic, social and cultural rights. Whilst the judiciary is not the only means of securing the realisation of such rights, the existence of an independent judiciary is an essential requirement for the effective involvement of jurists in the enforcement, by law, of such rights, given that they are often sensitive, controversial and such as to require the balancing of competing and conflicting interests and values. The Conference accordingly recalled existing principles such as the Bangalore Principles on the Domestic Application of International Human Rights Norms and urged that it be promoted at a universal level, with particular emphasis on economic, social and cultural rights.

Follow-up to the Conference

The participants resolved to request the ICJ to publish and disseminate the proceedings of the Conference and to ensure that the papers and the record of the reflections of the participants be widely distributed and publicised. The aim should be to enlarge awareness amongst jurists throughout the world of their proper and legitimate functions in promoting and securing the attainment of the economic, social and cultural rights which belong to humanity. The record of the Conference will reflect the sense of urgency and sometimes of professional failure and indifference, which has often marked, in the past, the response of lawyers to this area of human rights.

The Conference also recommended that the ICJ publish and disseminate for widespread discussion and action, some of the suggestions which were made during the Conference. Other such suggestions appear in the papers and record of the Conference. Together, such proposals constitute the Bangalore Plan of Action for the better attainment of economic, social and cultural rights in every land. To that end, all agreed that the Plan of Action which follows should be placed before jurists everywhere as a contribution to further reflection upon the role which they can play in the attainment of such rights. Jurists have a vital role in such attainment as stated in the United Nations Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers. Lack of involvement of jurists in the realisation of more than half of the field of human rights, vital to humanity, is no longer acceptable.

ANNEXE 5

Bangalore Plan of Action

At the International Level

The following actions for the full realisation of economic, social and cultural rights at an international level should be adopted :

1. The ICJ and other international and national human rights NGOs, should embark upon fresh action to attain universal ratification of the ICESCR.

2. Specific pressure should be applied to obtain more ratifications by countries in the Asia Pacific and other regions where ratifications of treaties are few. It should be supplemented by renewed consideration of the establishment of effective regional or sub-regional mechanisms for dealing with complaints about derogation from fundamental human rights (including economic, social and cultural rights);

3. Renewed efforts should be directed towards the adoption of an Optional Protocol to the ICESCR. The ICJ should take a leading role and ensure that such a Protocol is adopted without further delay;

4. The ICJ and other international human rights organisations should redouble their efforts to monitor and report upon departures in the realisation of economic, social and cultural rights. Where necessary, such NGOs should consider issuing alternative reports, to supplement the reports of Members States under the ICESCR. They should also create awareness in the communities affected about the Governments’ reports to the Committee so as to stimulate the political, legal and other action necessary to redress wrongs;

5. Treaty bodies of the United Nations need to develop mechanisms to allow NGOs to contribute and assist in their work. Pending such institutional reforms, NGOs should be imaginative and innovative to assist Treaty bodies even where not granted consultative or observer status.

6. NGOs should develop a strategy for drawing attention to defaults in reporting under the relevant treaties including by use of the national and international media;

7. The Inspection panel created by the World Bank should be supported to carry out its mandate effectively. Complaints and suggestions for the better attainment of the principles of the ICESCR should be made to the Panel by NGOs and jurists.

8. The attainment of economic, social and cultural rights in the international context in relation to other international initiatives requires a number of steps. Accordingly the ICJ and the NGO community should urgently develop steps to:

(i) monitor progressive compliance of State obligations under the ICESCR, and examine critically the spending of resources devoted to arms purchases and debt repayment;

(ii) ensure control of the international trade in arms and the huge burden of military expenditures;

(iii) control and redress corruption and offshore placement of corruptly obtained funds;

(iv) achieve an increase in the empowerment of women, including by general education and in particular by promoting the reproductive rights of women;

(v) bring about the reform of agricultural policies of certain developed countries arising from the uneconomic subsidisation of local agricultural production to the exclusion of markets for agricultural producers in developing countries; and

(vi) improve and make more efficient the functioning of the regional systems and bodies with respect to the attainment of economic, social and cultural rights.

At the National Level

The following action, amongst others should be taken at a national level:

1. An increase in the sensitisation of judges, lawyers, government officials and all those concerned with legal institutions as to the terms and objectives of the ICESCR, its mechanism, other relevant treaties and the vital importance for individuals of these aspects of human rights as well as the legitimate role of jurists in attaining them. Universities, law colleges, judicial training courses and the general media also have a responsibility to promote greater awareness of such rights and their legal content; they should therefore be encouraged to assume this responsibility.

2. Specifying those aspects of economic, social and cultural rights which are more readily susceptible to legal enforcement requires legal skills and imagination. It is necessary to define legal obligations with precision, to define clearly what constitutes a violation; to specify the conditions to be taken as to complaints; to develop strategies for dealing with abuses or failures and to provide legal vehicles, in appropriate cases, for securing the attainment of the objectives deemed desirable;

3. Amongst specific actions to be taken where appropriate, the following were endorsed :

3.1. Reform of constitutional provisions, where necessary, to incorporate references to economic, social and cultural rights.

3.2. Revision of other municipal law to state in precise and justiciable terms, economic, social and cultural rights in a way susceptible to legal enforcement;

3.3. Reform of the law of standing and encouragement of public interest litigation (such as has occurred in India) by test cases, to further and stimulate the political process into attention to economic, social and cultural rights and to afford priority to the hearing of such cases.

3.4. Establishment and enhancement of the functions and powers of the Ombudsman or of specialised Ombudsmen, to provide accessible and independent agencies for receiving complaints against government and others concerning departures from the obligations to ensure the attainment of economic, social and cultural rights.

4. The growth and sustenance of an independent judiciary should be encouraged. Steps should be taken to ensure the continuous sensitisation of the judiciary on their role in promoting and protecting these rights.

5. Other steps necessary to ensure real progress in the attainment of these ends, include :

5.1. The adoption of effective means of independent public legal aid and like assistance in appropriate cases;

5.2. The provision by Bar Associations and Law Societies of pro bono services and the enlargement of their agendas in the field of human rights to involve the services of their members in this regard;

5.3. Empowerment of disadvantaged groups, including women, minorities, indigenous peoples and others lacking legal experience and confidence in the legal system, to encourage them to come forward to claim and secure their rights and the need for court procedure, to adapt to these ends;

5.4. Judges should apply domestically international human rights norms in the field of economic, social, and cultural rights. Where there is ambiguity in a local constitution or statute or an apparent gap in the law, or inconsistency with international standards, judges, should resolve the ambiguity or inconsistency or fill the gap by reference to the jurisprudence of international human rights bodies. Renewed efforts should be made, including by the ICJ, to promote the existing principles such as the Bangalore Principles, on the universal level with particular emphasis on economic, social and cultural rights.

Action by Individuals

Jurists as individuals should take the following action:

1. Action within Bar Associations and Law Societies to add a focus upon economic, social and cultural rights to their agenda for the attainment of human rights in full measure;

2. As legislators, community leaders and as citizens to enlarge governmental and community knowledge about, and understanding of, social, economic and cultural rights, so that the obligations of the ICESCR and other relevant treaties will become better known; and

3. Use by jurists, in addition to the courts and tribunals, of other independent organs such as the Ombudsman, independent Human Rights Commissions, as well as national, regional and international bodies to promote the attainment of the standards of relevant treaties. In States in which such institutions have not been established, jurists should promote their establishment. Jurists should work closely with the institutions of civil society to help promote and attain the objectives of the ICESCR and other relevant treaties in full measure.