Nov 19, 2020 | News

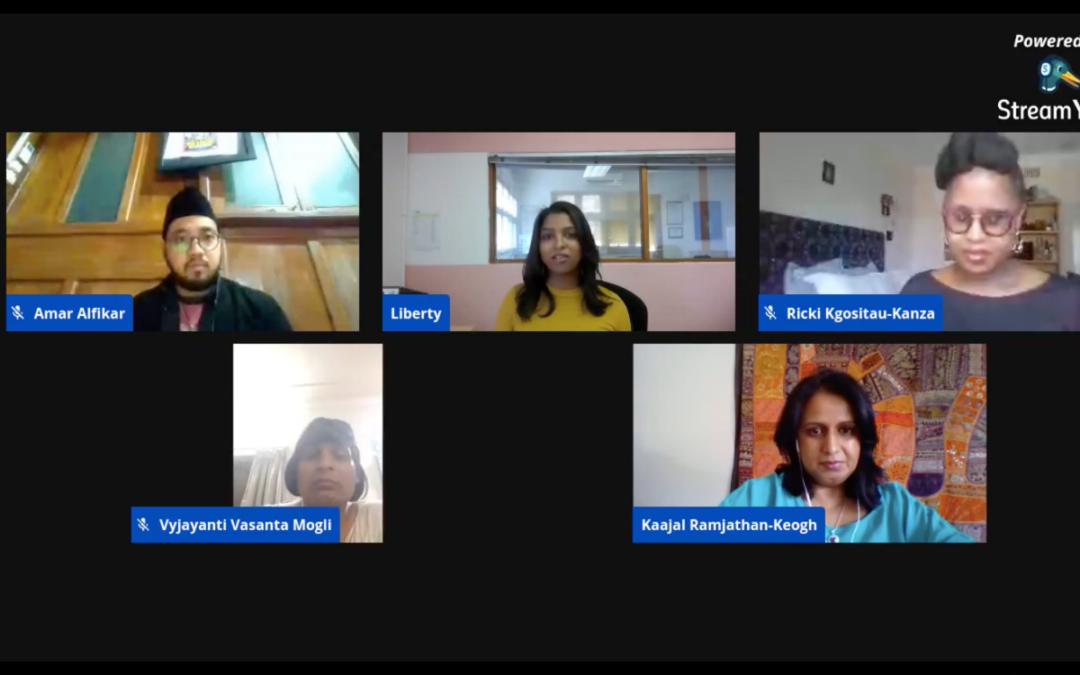

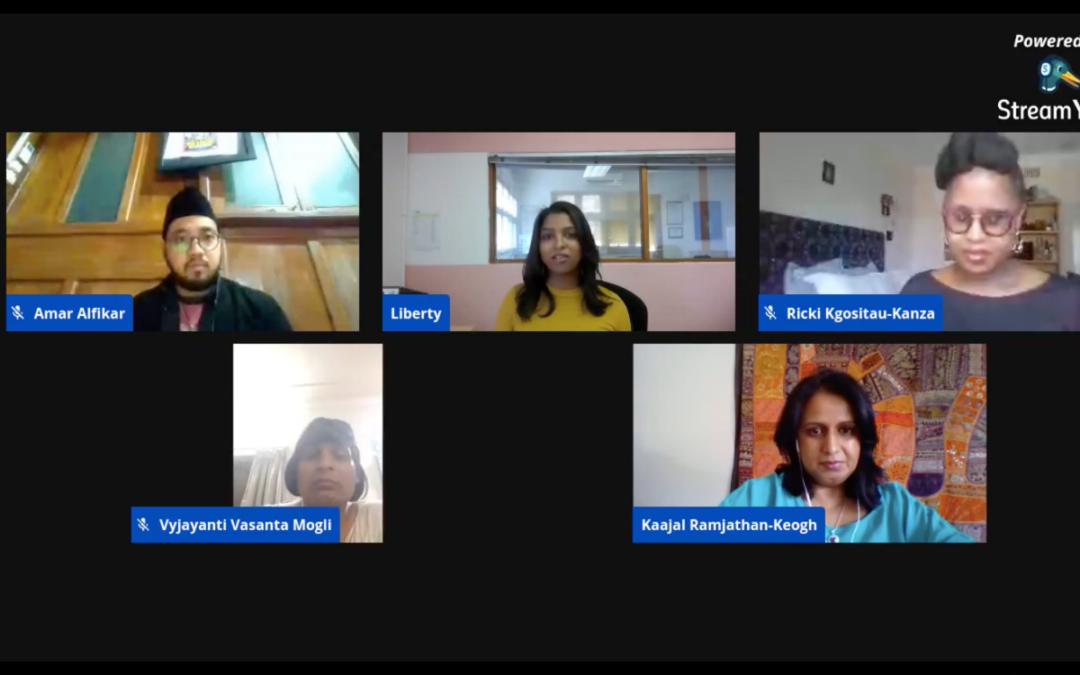

On 18 November 2020, the ICJ hosted a Facebook Live with four transgender human rights activists from Asia and Africa. It highlighted the stark reality between progressive laws and violent lived realities of transgender people.

The 20th November 2020 marks the Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR), the day when transgender and gender diverse people who have lost their lives to hate crime, transphobia and targeted violence are remembered, commemorated and memorialized.

The discussions focused on their individual experiences of Transgender Day of Remembrance in their local contexts, the impact of COVID-19 on transgender communities and whether laws are enough to protect and enforce the human rights of transgender and gender diverse people.

The renowned panelists were from four different countries, Amar Alfikar from Indonesia, Liberty Matthyse from South Africa, Tshepo Ricki Kgositau-Kanza from Botswana and Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli from India. The panel was moderated by the ICJ Africa Regional Director, Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh.

The panel aimed to provide quick glimpses into different regional contexts and a platform for transgender human rights activists’ voices on the meaning of Transgender Day of Remembrance and the varied and devastating impacts of COVID-19 on transgender people.

The speakers discussed the meaning that they individually ascribe to Transgender Day of Remembrance. A common theme running across the conversations was that it is not enough to highlight issues and concerns of the transgender community only on this day. Instead, these discussions should be part of daily conversations about the human rights of transgender people at the local and international level.

Liberty Matthyse discussed the importance of remembering the transgender persons who have lost their lives over the past years, and added:

“South Africa generally is known as a country which has become quite friendly to LGBTI people more broadly and this, of course, stands in stark contradiction to the lived realities of people on the ground as we navigate a society that is excessively violent towards transgender persons and gay people more broadly.”

Amar Alfikar describes his work as “Queering Faiths in Indonesia”. This informs his understanding of what Transgender Day of Remembrance means in his country and he believes that:

“Religion should be a source of humanity and justice. It should be a space where people are safe, not the opposite. When the community and society do not accept queer people, religion should start giving the message, shifting the way of thinking and the way of narrating, to be more accepting, to be more embracing.”

It was clear from the discussions that a lot of the issues that have become prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic, have not arisen due to the pandemic. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has had the effect of a magnifying glass, amplifying existing challenges in the way that transgender communities are treated and driven to margins of society. Speaking about the intersectionality of transgender human rights, Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli said:

“I don’t think LGBT rights or transgender rights exist in isolation, they are part of a larger gamut of climate change, racial equality, gender equality, the elimination of plastics, and all of that.”

The panelists had different opinions on whether it is enough to rely on the law for the recognition and protection of the human rights of transgender individuals.

The common denominator, however, was that the laws as they stand have a long way to go before fully giving effect to the right of equality before the law and equal protection of the law without discrimination of transgender people.

Tshepo Ricki Kgositau-Kanza, who was a litigant in a landmark case in Botswana in which the judiciary upheld the right of transgender persons to have their gender marker changed on national identity documents, explained the challenges with policies which, on their face, seem uniform:

“Uniform policies… are very violent experiences for transgender persons in a Botswana context where the uniform application of laws and policies is binary and arbitrarily assigned based on one’s sex marker on one’s identity document which reflects them either as male or female. Anybody in between or outside of that kind of dichotomy is often rendered invisible and vulnerable to a system that can easily abuse them.”

This conversation can be viewed here.

Contact

Tanveer Jeewa, Communications Officer, African Regional Programme, e: tanveer.jeewa(a)icj.org

Nov 17, 2020 | News

The ICJ today denounced the renewed threat of criminal proceedings by prosecutorial authorities against Judge Igor Tuleya on charges arising from the judge’s independent exercise of his judicial functions, as his case is appealed before a panel of the Supreme Court Disciplinary Chamber.

Judge Tuleya faces prosecution for having allowed the presence of media in a sensitive case concerning the investigations on the 2017 budget vote in the Polish House of Representatives (Sejm) that took place without the presence of the opposition.

He has been charged with ‘failing to comply with his official duties and overstepping his powers’ for having allegedly disclosed a secret of the investigation to ‘unauthorized parties’.

The accusations stem from the initiative of the judge to allow media and the public in the courtroom while issuing his ruling. Usually rulings on investigations are issued behind closed doors in Poland, but the criminal procedure code allows judges to make the hearing public “in the interest of justice”.

“Judge Tuleya’s immunity should be maintained. Actually he should not face any criminal proceedings to begin with as its decisions were in accordance with the law and the principles of transparency and public trials,” said Massimo Frigo, Senior Legal Adviser for the ICJ Europe and Central Asia Programme.

“His case is a further demonstration of the relentless attacks against the independence of judges ongoing in Poland.”

The Disciplinary Chamber, in a single-judge formation, upheld Judge Tuleya’s immunity on 9 July but the prosecution appealed the ruling that will be now decided by the same Chamber before a three-judge panel, Tomasz Przelawski, Slawomis Niedzielak and Jaroslaw Sobutka.

These proceedings are the first case of implementation the draconian Act amending the Law on the Common Courts, the Law on the Supreme Court and Some Other Laws, signed into law on 4 February and widely known as the ‘Muzzle Act’, which has given competence to waive judicial immunity to the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court.

“Immunity claims against a judge should be decided only by an independent body,” Massimo Frigo added.

“As EU Court of Justice held, the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court is not independent and is open to undue influence or interference by political authorities. It should therefore not rule on this case.”

Background

On 19 November, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) delivered a ruling in the case A.K. and others (C-585/18, C-624/18, C-625/18), on a preliminary question by the Supreme Court of Poland. The preliminary question asked whether the recently established Disciplinary and Extraordinary Chambers of the Supreme Court could be considered to be independent.

The CJEU ruled that a court cannot be considered independent “where the objective circumstances in which that court was formed, its characteristics and the means by which its members have been appointed are capable of giving rise to legitimate doubts, in the minds of subjects of the law, as to the imperviousness of that court to external factors, in particular, as to the direct or indirect influence of the legislature and the executive and its neutrality with respect to the interests before it and, thus, may lead to that court not being seen to be independent or impartial with the consequence of prejudicing the trust which justice in a democratic society must inspire in subjects of the law.”

Based on this ruling, the Labour, Criminal and Civil Chambers of the Supreme Court declared that the Disciplinary and Extraordinary Chambers of the Supreme Court were not properly constituted and independent.

According to the UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, judges are entitled to a fair hearing in all disciplinary proceedings (principle 17). In order for such a hearing to be fair, the decision-maker must be independent and impartial.

International and European standards on the independence of the judiciary provide that judges should have immunity from criminal prosecution for decisions taken in connection with their judicial functions in the absence of proof of malice, and any procedure for removing immunity must itself be independent (see for instance, UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, paras 65-67 and 98; Council of Europe Committee of Ministers, para 68; Consultative Council of European Judges, para 20; ICJ Practitioners Guide no 13, pp. 27-30).

On 26 February 2020, the Polish Prosecutor’s Office requested a waiver of Judge Tuleya’s immunity in order to press criminal charges which might lead to imprisonment. The waiver was rejected on 9 June 2020 by the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court appointed by the government, in a single-judge formation. The Prosecutor’s Office appealed the ruling. The case will be now considered by the same Disciplinary Chamber in a three-judge formation. A first hearing was scheduled for 5 October 2020 but was postponed. It will take place on 18 November.

In an open letter of 5 February 2020, 44 ICJ Commissioners and Honorary Members denounced the recent legislative changes adopted by the Polish government threatening the role and the rights of judges and denouncing the risks faced by legal practitioners when fighting for the rule of law. Two weeks later, the risks highlighted by the letter have become reality for an increasing number of Polish judges, including Judge Tuleya.

Contact:

Massimo Frigo, Senior Legal Adviser, Europe and Central Asia Programme, e: massimo.frigo(a)icj.org, t: +41 797499949

Nov 16, 2020 | Advocacy, News

Today, the ICJ calls on the Ukrainian authorities to abandon a draft law which would dismiss the judges of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, as a means of retaliation for a decision adopted by the Court and in order to circumvent the decision.

The authorities should also refrain from any other actions, including harassment of judges, which undermine the independence of the Constitutional Court.

“This draft law constitutes a direct attack on the ability of the judiciary to exercise its functions independently. It is incompatible with basic principles of the rule of law and the separation of powers, and with international standards on the independence of the judiciary,” said Róisín Pillay, Director of the ICJ Europe and Central Asia Programme.

“By the nature of their role, the judiciary, and especially constitutional courts may be required to decide on controversial matters. It is however essential that particularly in such cases, courts are able to operate without fear of retaliation or repression for the decisions they take,” she added.

The draft law on Restoring Public Confidence in the Constitutional Court, submitted by President Zelensky to the Ukrainian Parliament (Verkhovna Rada), aims to pronounce a decision of the Constitutional Court on anti-corruption legislation “void” and without legal consequences.

This runs contrary to the Ukrainian Constitution according to which “[d]ecisions and opinions adopted by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine shall be binding, final and may not be challenged” (Article 151-2).

The draft law would terminate the mandate of the judges of the Constitutional Court, in contravention of the Constitution of Ukraine as well as basic principles of independence of the judiciary, governing appointments, dismissal and security of tenure of judges.

The draft law provides that the powers of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine in force at the time of the decision on the anti-corruption law would be terminated from the date of entry into force of the law.

According to the explanatory note to the Draft Law, one reason the adoption of the law would be justified is because there had not been a “proper substantiation” of its judgment on the anti-corruption law. The note alleges that Court’s decision was adopted in the private interests of judges of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, that its proper substantiation was not provided and that it contradicts the principle of the rule of law and denies the European and Euro-Atlantic choice of the Ukrainian people. The ICJ considers these allegations are inappropriate as they directly interfere with the judicial function of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, contrary to the national legislation and international law on the independence of the judiciary.

On 2 November 2020, Oleksandr Tupitsky, the President of the Constitutional Court was summoned for interrogation by the State Investigation Bureau in connection with allegations against him of committing crimes as part of an organized group. The ICJ fears that this may be a form of pressure in relation to the Constitution Court’s decision.

Following these incidents, the Constitutional Court has stopped working as four of the judges refuse to take part in its sessions. The Court therefore lacks the necessary quorum to operate.

The ICJ calls on Ukraine to withdraw the draft law, and to refrain from any further reprisals against judges for their decisions.

Download

Ukraine-draft law constitutional court-News-ENG-2020 (full statement with background information)

Nov 15, 2020 | News

The removal of Peru’s President Martin Vizcarra by the country’s Congress has undermined respect for the principle of separation of powers and precipitated a rule of law crisis, the ICJ said today.

On 9 November, Peru’s Congress used the seldom-used article 113(2) of the country’s constitution to ‘vacate’ Vizcarra’s term on the ground of “permanent moral incapacity” for office and swore in the President of the Congress, Manuel Merino, as President of the country.

The underlying justification for Vizcarra’s removal was allegations of corruption stemming from the time when he was Governor of Moquequa state in 2011-2014. Those allegations are already under investigation by the Office of the Prosecutor.

The ICJ notes that Peru’s Constitutional Court has a pending case to review the constitutional consistency of the use of the grounds of “permanent moral incapacity” clause for ordinary crimes. The Peruvian Constitution contemplates a separate procedure of impeachment that has not been followed in this case. Yet Congress applied the clause of “moral incapacity” in hasty proceedings with that decision pending.

“Peru’s congress has preempted the decision of the Constitutional Court and applied an overly expansive and highly contested legal interpretation of article 113(2) to oust a president, thus implicating the authority of the Judicial branch as well as the Executive,” said ICJ Secretary General Sam Zarifi.

“This overreach by the Legislative branch has launched the country into a rule of law crisis that also threatens respect for human rights in the country,” he added.

Protesters demonstrating against Vizcarra’s removal have faced ill-treatment and arbitrary arrest by police and security forces.

The ICJ calls on the Peruvian authorities to respect the right to freedom of assembly and peaceful protest and to desist from any form of unlawful use of force. Allegations of violations of ill-treatment and other human rights violations must be investigated promptly, thoroughly and impartially. The ICJ also urges respect of the independence of the judiciary, particularly as concerns the Constitutional Court and its functions.

Nov 14, 2020 | Advocacy, News

On 12-13 November 2020, the ICJ co-hosted a discussion on “Thailand’s National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights: 1-Year Progress Review” in Bangkok. The forum was co-organized with other 11 organizations.

Participants on the first day included some 95 individuals representing populations affected by business operations from all regions of Thailand and members of civil society organizations. The considered reviewed the progress that has been made by Thailand over the past year towards fulfilling its commitments in the four priority issues in its First National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights (NAP): (1) Labor; (2) Land, environment and natural resources; (3) Human rights defenders; and (4) Cross border investment and multi-national enterprises.

Several participants noted a lack of any evident and tangible progress in the NAP implementation and questioned the effectiveness of the NAP because it does not have the status of a law but is merely a resolution from the Council of Ministers. They further expressed concern at the lack of a comprehensive monitoring system in place to monitor NAP and its achievement according to the key recommendations aligned with the UN Guiding Principle on Business and Human Rights, and on legal harassment and intimidation faced by human rights defenders.

In the session regarding cross border investment and multi-national enterprises, the ICJ participants led the discussion regarding challenges to hold Thai companies accountable for human rights abuses which took place abroad. The participants looked into several obstacles to accessing to justice for victims of business-related human rights abuses in the context of cross-border investment. The discussion was based on the ICJ’s work and analysis in the draft report on the human rights legal framework of Thai companies operating in Southeast Asia, which is expected to be launched in December 2020.

Comments and recommendations raised by participants on the first day were presented to representatives from the Ministry of Justice, Thailand National Human Rights Commission, Global Compact Network Thailand and UN agencies, in the public seminar on the second day. The outcomes of the discussion and recommendations will also be submitted to the NAP Monitoring/Steering Committees, chaired by Director-General of Rights and Liberties Protection Department, Ministry of Justice.

Background

On 29 October 2019, the Cabinet approved and adopted the First National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights (2019-2022), making Thailand the first country in Asia to adopt the stand-alone NAP.

The NAP emphasizes the duties of State agencies to review and amend certain laws, regulations and orders that are not in compliance with human rights laws and standards and ensure their full implementation; ensure accessibility of mechanisms for redress and accountability for damage done to affected communities and individuals; overcome the barriers to meaningful participation of communities and key affected populations; and strengthen the role of businesses to “respect” human rights on a variety of key priority issues.

The event was co-hosted with:

- International Organization for Migration (IOM)

- Community Resource Centre Foundation (CRC)

- Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

- EarthRights International (ERI)

- The Mekong Butterfly (TMB)

- International River (IR)

- Spirit in Education Movement (SEM)

- Thai Extra-Territorial Obligations Working Group (Thai ETOs Watch)

- Green Peace Thailand

- Green South Foundation

- Business and Human Rights Resource Center (BHRRC)

Further reading

Thailand’s Legal Frameworks on Corporate Accountability for Outbound Investments

Thailand: ICJ co-hosts discussion on National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights

Nov 12, 2020 | Agendas, Events, News

The International Commission of Jurists and the Human Rights Joint Platform (IHOP) invite you to a Zoom workshop where Turkish and international experts will discuss the legacy of the 2016-2018 state of emergency in Turkey for access to justice today.

To participate, please register by writing an email to ihop@ihop.org.tr (the Human Rights Joint Platform)

Join our great panel of speakers:

– Professor Sarah Cleveland, ICJ Commissioner

– Dr. Dilet Kurban, Hertie School

– Lawyer Ziynet Özçelik, Ankara Bar Association

– Dinçer Demirkent, Human Rights School

– Roisin Pillay, Director of ICJ Europe and Central Asia Programme

– Kerem Altiparmak, ICJ Turkey Legal Adviser

The workshop will address how state of emergency measures, such as dismissals and closures of legal entities, still impact on the human right of people in Turkey today.

The experts will discuss whether the remedies set up by Turkish authorities are up to standard with Turkey’s international human rights law obligations.

IHOPICJ-ZoomWorkshop-StateofEmergency-Agenda-2020-ENG (download the agenda in English)

IHOPICJ-ZoomWorkshop-StateofEmergency-Agenda-2020-TUR (download the agenda in Turkish)

The event is part of the REACT project: implemented jointly by ICJ and IHOP, this project seeks to support the role of civil society actors in turkey in ensuring effective access to justice for the protection of human rights. This project is funded by the European Union. The views expressed in the event do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the EU.