Feb 4, 2021 | Advocacy, News

The ICJ, in a letter to the Chairperson of the African Union, recommended that the African Union acknowledge that COVID-19 vaccines are a “public good” and all States must ensure access to these vaccines in order to realize the human rights of their inhabitants.

The African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, to which most AU Member States are Party, provides that “every individual shall have the right to enjoy the best attainable state of physical and mental health” (Art 16(1)). The Charter also places an obligation on the States Parties to take all “necessary measures to protect the health of their people and to ensure that they receive medical attention when they are sick” (Art 16(2)).

This obligation must be understood consistently with the equivalent Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Cultural and Social Rights (ICESCR), to which most AU Member States are also Party. That provision protects the right to the “highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”, and requires States to take all necessary measures to realize this right including to ensure “the prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases” (Art 12(1)(c)). Vaccines, for some such diseases including COVID-19, are necessarily an integral part of prevention, treatment and control.

“It is essential for the process of vaccine procurement and allocation to be in line with international human rights standards. The African continent and its people cannot afford to be left behind, and the best way to ensure that does not happen is to move forward and prioritize each individuals right to health and corresponding human rights.” –

Justice Sanji Monageng, ICJ Commissioner, Botswana

Therefore, under these treaties and other internationally binding human rights law, it is clear access to certain vaccines is necessary to fulfill a human right, must not be seen as a privilege. Vaccines are a public good and should be treated as such by States. This understanding was affirmed by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) in December in a statement on universal and equitable access to vaccines. CESCR stressed that: “every person has a right to have access to a vaccine for COVID-19 that is safe, effective and based on the application of the best scientific developments”. It further implored States to “give maximum priority to the provision of vaccines for COVID-19 to all persons”.

Recommendations of the International Commission of Jurists

The AU will be expected by the constituents of its Members to fulfil its proper leadership function in terms its Constitutive Act an ensure the promotion and protection of human rights in Africa. To this end, the ICJ calls upon the AU to adopt resolutions:

- Calling on all member States to ensure that their COVID-19 responses, including vaccine acquisition and distribution, comply with international human rights law and standards including those particularly relating to the rights to health and to duty ensure this right is realized through international cooperation.

- Calling on all member States to endorse and fully participate in the WHO’s COVID-19 Technology Access Pool.

- Calling on all member States to openly support the approval and implementation of a waiver of intellectual property rights in terms of the TRIPS agreement in order to ensure equitable and affordable access of COVID-19 vaccines and treatment for all.

- Calling on all member States to urgently publish public, comprehensive vaccine rollout plans and transparently provide clear and full health-related information to their populations.

- Calling on all participants in COVAX to endorse and fully participate in the WHO’s COVID-19 Technology Access Pool.

- Calling on the WTO to respond expeditiously and favourably to the proposal communicated by India and South Africa for waiver of IP protection for vaccines.

To read the full submission, click here.

Contact

Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh, ICJ Africa Director Kaajal.Keogh(a)icj.org +27 84 5148039

Tanveer Jeewa, Media and Legal Consultant Tanveer.Jeewa(a)icj.org

Jan 26, 2021 | News

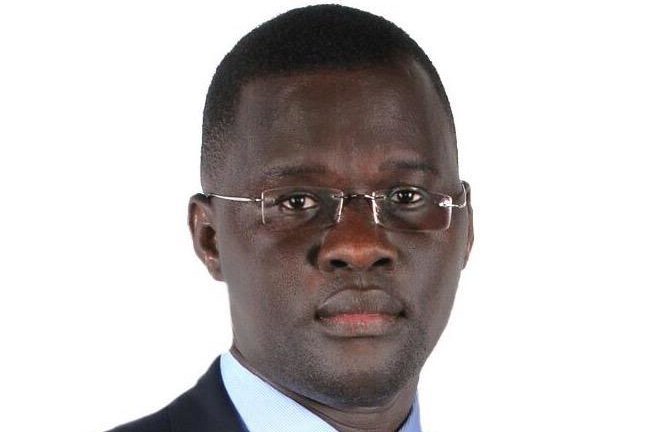

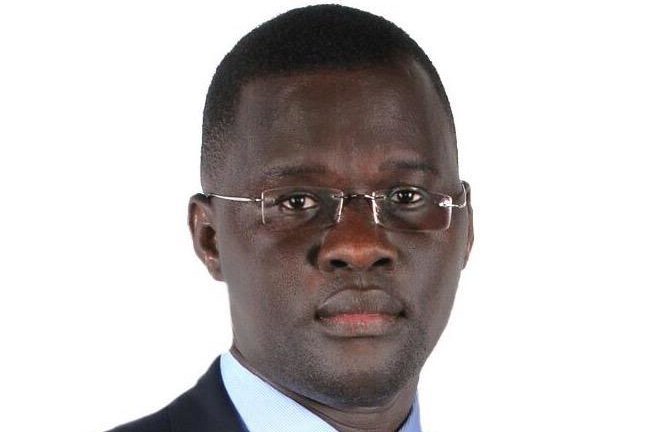

Lawyers for Lawyers (L4L) and the ICJ condemn the spurious charges under the Anti-Money Laundering brought against Ugandan lawyer and human rights defender Nicholas Opiyo and call for them to be dropped.

The organizations consider that this action stands to impede work of lawyers in the country of carrying out their professional functions, particularly regarding human rights work.

There do not appear to be legitimate grounds for these charges or the ongoing prosecution. The organizations are further concerned at numerous alleged violations surrounding the arrest, detention and pre-trial proceedings.

Nicholas Opiyo, Executive Director of Chapter Four Uganda, a civil rights charity working to defend human rights and civil liberties, was arbitrarily arrested on 22 December 2020, not informed of the reason for his arrest and effectively held in incommunicado detention for a prolonged period.

On 22 December 2020, plain clothed law enforcement officers who did not identify themselves seized Mr. Opiyo from a restaurant, along with four other individuals, including three lawyers.

He was later charged under section 3 (c) of the Anti-Money Laundering Act on allegations that he acquired USD 340,000 through the bank account of Chapter Four Uganda, knowing that “the said funds were proceeds of crime”.

Chapter Four Uganda have confirmed that these are legitimate donor funds for lawful purposes.

Sophie de Graaf, the Director of Lawyers for Lawyers, said:

“Lawyers play a vital role in the protection of the rule of law and human rights. It is the responsibility of lawyers to protect and establish the rights of citizens from whatever quarter they may be threatened. Their work is indispensable for ensuring effective access to justice for all. To fulfil their professional duties effectively, lawyers should be able to practice law freely and independently, without any fear of reprisal.”

Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh, ICJ’s Africa Director, added:

“Uganda is required under its Constitution and under its international legal obligations, to respect and protect the independence of lawyers. These baseless charges seek to intimidate and harass Mr. Opiyo and interfere with his work as a lawyer”.

Lawyers for Lawyers and the ICJ call on the Ugandan authorities to drop the spurious charges against Mr. Opiyo and to ensure that his rights to due process and fair trial are fully respected.

The organizations emphasize that the responsibilities authorities must comply with Uganda’s international legal obligations to ensure that members of the legal profession can carry out their professional functions without harassment and improper interference, including arbitrary arrest and incommunicado detention.

Background

Article 23 of Uganda’s Constitution stipulates that suspects under detention should be brought before a court of law within 48 hours from the time of arrest. Article 27 of Uganda’s Constitution requires that a person charged with a criminal offence should be informed immediately of the charges against them. Article 28 of the Ugandan Constitution guarantees for every person the right to a fair hearing and the right to legal representation. These rights are protected under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights, to which Uganda is a party.

International and regional standards on ensuring the independence of lawyers are set out in the UN Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers (UN Basic Principles) and the Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa.

Contact:

Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh, ICJ Africa Director Kaajal.Keogh(a)icj.org +27 84 5148039

Tanveer Jeewa, Media and Legal Consultant Tanveer.Jeewa(a)icj.org

Jan 18, 2021 | News

The ICJ today condemned the arbitrary arrests in recent days of prominent Zimbabwean human rights defenders Hopewell Chin’ono, Fadzayi Mahere and Job Sikhala, who have been critical of the government led by President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

The ICJ is concerned that their arrests and potential prosecutions are based solely on their exercise of protected human rights, including freedom of expression. The ICJ calls for their immediate release and the dropping of the charges against them.

The three have been charged with contravening section 31 of the Criminal Code which prohibits “publishing or communicating false statements prejudicial to the state”.

The alleged offences arise from posts made on social media and comments issued by all three in connection with an incident at a Harare taxi rank in which a police officer is alleged to have assaulted a mother with a baby on her back.

ICJ’s Africa Director Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh said:

“The use of judicial processes to silence these three human rights defenders constitutes a continuing assault on members of the bar and journalists and is a clear attempt to chill others from carrying out their professional functions when these activities offend government authorities. Of concern is the continued use of criminal defamation (section 31) charges which were declared unconstitutional in 2014 yet continues to be weaponised against human rights defenders.”

Chin’ono, a journalist, was arrested on 8 January and had his application for bail rejected on 14 January. He has been handcuffed and held in leg irons during court appearances, despite a Magistrate’s ruling on 12 January that forcing Chin’ono to be shackled in leg irons and handcuffing him amounts to inhumane and degrading treatment.

Mahere is a lawyer and spokesperson of the opposition political party Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) Alliance. She was arrested on 11 January. On 15 January Magistrate Trynos Utahwashe failed to hand down his ruling on her application for bail as required.

Bail was however granted today. Mahere did raise concerns about the absence of essential COVID-19 measures in her detention, including the lack of temperature checks or sanitisers at the entrance to the police station; the failure to practice social distancing in the waiting area or holding cells; the unavailability of masks in the cells and use of old masks by cellmates; as well as the failure to provide sanitary materials to female inmates.

Sikhala is a human rights lawyer, the MDC Alliance Vice National Chairperson, and MP for Zengeza West.

He was part of Chin’ono’s legal team. On 15 January Magistrate Ngoni Nduna dismissed his bail application stating that there was overwhelming evidence against him not to grant it. He remains in prison custody while he awaits trial. Sikhala has also been handcuffed and held in leg irons during court appearances.

Ramjathan-Keogh added:

“The courts have unlawfully employed the denial of bail as well as the repeated prolonged bail proceedings as a punitive tool in these cases. Pre-trial detention without the opportunity for bail, with exceptions not applicable here, is a violation of the right to liberty. The government has an obligation to provide safe and humane conditions of detention.”

The ICJ recalls that that Zimbabwe’s Constitution guarantees the rights to freedom of expression and freedom of the media (Article 61); freedom from arbitrary detention (Article 50). Zimbabwe has an international legal obligation to protect these rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Article 9 and 19) and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Articles 6 and 9).

Contact:

Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh, Director of ICJ Africa Programme, e: Kaajal.Keogh(a)icj.org ; t: +27845148039

Tanveer Jeewa, Legal and Communications Consultant, e: Tanveer.Jeewa(a)icj.org

Background Information:

Hopewell Chin’ono has been arrested on three separate occasions. He has been denied bail on each occasion and those bail proceedings have been unduly and unfairly prolonged. He was initially arrested in July 2020 after he expressed support on Twitter for an anti-corruption protest, which was planned for 31 July. He was charged with incitement to participate in public violence and breaching anti-corona virus health regulations.

He appeared in court three times to apply for bail and was only granted bail in September 2020, nearly two months after his arrest. On 3 November 2020, he was re-arrested for contempt of court for allegedly violating section 182(1)(a) or (b) of the Criminal Code because of a tweet he posted. His tweet stated: “On day of bail hearing CJ was seen leaving court in light of what has been said by judges what does this say.” The arrest violates Zimbabwe’s constitutional provisions, in particular, section 61, which provides for freedom of expression and the right of a journalist to practice his profession. He was again arrested on 8 January 2021 for allegedly communicating falsehoods by tweeting that police beat a baby to death.

Chin’ono was in 2020 denied access to the legal representative of his choice. The magistrate’s order barring lawyer Beatrice Mtetwa from continuing as defence legal counsel for Chin’ono violated his right to a fair trial and Mtetwa’s right to express her opinions freely. See ICJ’s statement of 21 August 2020.

Dec 16, 2020 | News

Dialogue between Swazi Women Human Rights Defenders and CEDAW Committee Members highlights the obstacles faced by local women in the enjoyment of their human rights.

On 14 December 2020, the ICJ and the Southern Africa Human Rights Defenders Network (SAHRDN) facilitated a fruitful dialogue between Swazi Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRD) and members of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (the CEDAW Committee) on the key human rights concerns facing Swazi women and possible advocacy strategies to address them.

The CEDAW Committee monitors State parties’ compliance with and implementation of their human rights obligations under the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (the Convention), by which Eswatini is bound.

In light of the Eswatini government’s failure to submit a report to the CEDAW Committee, as required under the Convention, more than 20 Swazi WHRDs’ organizations had a preparatory meeting on 8 December to discuss and prioritize the human rights concerns they wished to bring to the CEDAW Committee members’ attention.

They hoped that, by coming together and agreeing on these issues, they may raise awareness and put pressure on the Eswatini government to comply with its obligations under the Convention, including by promptly submitting the country’s overdue report.

In the wake of this preparatory meeting, on 14 December Swazi WHRDs briefed the CEDAW Committee members about the most critical human rights violations faced by women in Eswatini. This meeting was broadcasted live on Facebook.

The dialogue focused on the Eswatini authorities’ failure to implement their human rights obligations under the Convention, including the previous Concluding Observations of the CEDAW Committee.

High rates of teenage pregnancy, women’s inadequate access to education, healthcare and adequate housing, and ways in which customary and religious laws are used to justify discrimination against them were among the key human rights concerns affecting women discussed during the dialogue.

Watch the animation on CEDAW

Nov 19, 2020 | News

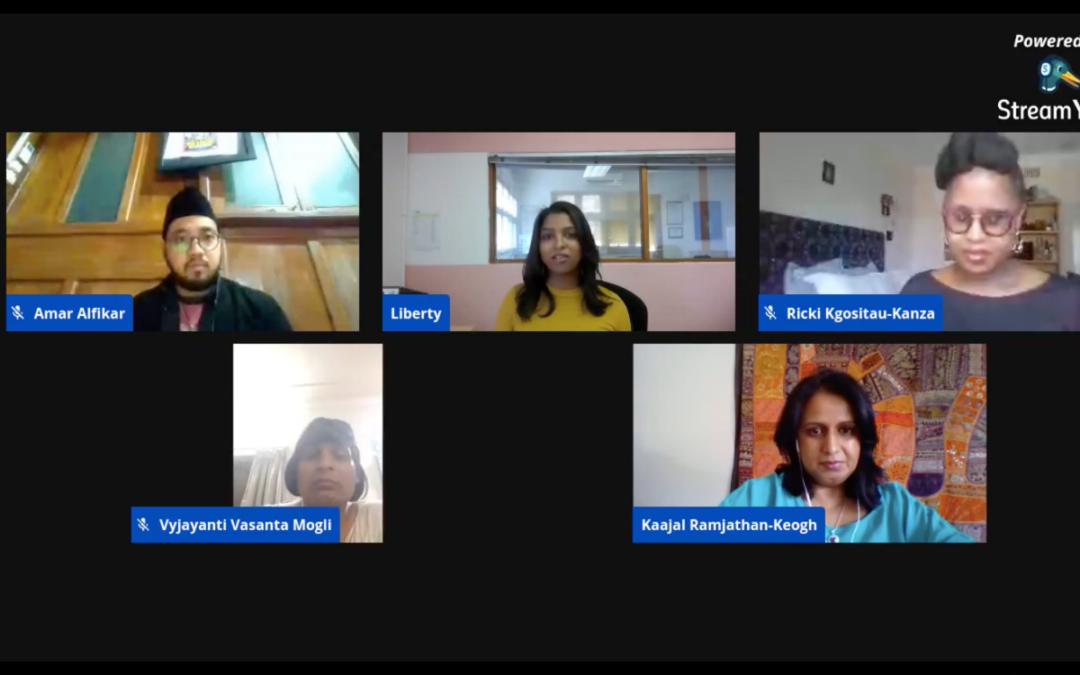

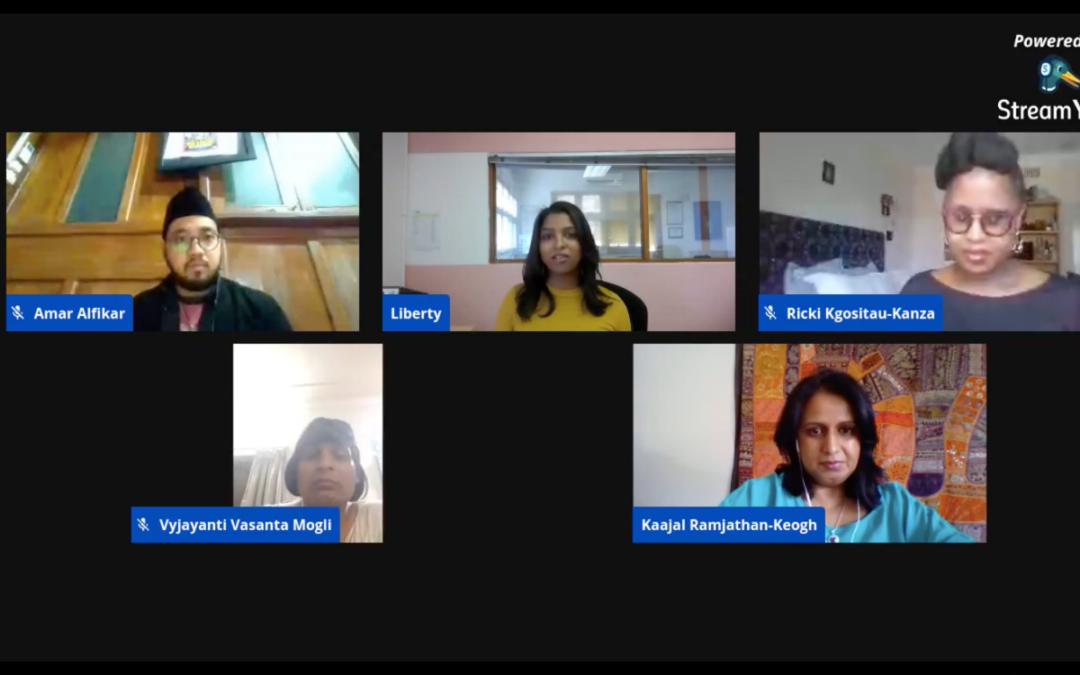

On 18 November 2020, the ICJ hosted a Facebook Live with four transgender human rights activists from Asia and Africa. It highlighted the stark reality between progressive laws and violent lived realities of transgender people.

The 20th November 2020 marks the Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR), the day when transgender and gender diverse people who have lost their lives to hate crime, transphobia and targeted violence are remembered, commemorated and memorialized.

The discussions focused on their individual experiences of Transgender Day of Remembrance in their local contexts, the impact of COVID-19 on transgender communities and whether laws are enough to protect and enforce the human rights of transgender and gender diverse people.

The renowned panelists were from four different countries, Amar Alfikar from Indonesia, Liberty Matthyse from South Africa, Tshepo Ricki Kgositau-Kanza from Botswana and Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli from India. The panel was moderated by the ICJ Africa Regional Director, Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh.

The panel aimed to provide quick glimpses into different regional contexts and a platform for transgender human rights activists’ voices on the meaning of Transgender Day of Remembrance and the varied and devastating impacts of COVID-19 on transgender people.

The speakers discussed the meaning that they individually ascribe to Transgender Day of Remembrance. A common theme running across the conversations was that it is not enough to highlight issues and concerns of the transgender community only on this day. Instead, these discussions should be part of daily conversations about the human rights of transgender people at the local and international level.

Liberty Matthyse discussed the importance of remembering the transgender persons who have lost their lives over the past years, and added:

“South Africa generally is known as a country which has become quite friendly to LGBTI people more broadly and this, of course, stands in stark contradiction to the lived realities of people on the ground as we navigate a society that is excessively violent towards transgender persons and gay people more broadly.”

Amar Alfikar describes his work as “Queering Faiths in Indonesia”. This informs his understanding of what Transgender Day of Remembrance means in his country and he believes that:

“Religion should be a source of humanity and justice. It should be a space where people are safe, not the opposite. When the community and society do not accept queer people, religion should start giving the message, shifting the way of thinking and the way of narrating, to be more accepting, to be more embracing.”

It was clear from the discussions that a lot of the issues that have become prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic, have not arisen due to the pandemic. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has had the effect of a magnifying glass, amplifying existing challenges in the way that transgender communities are treated and driven to margins of society. Speaking about the intersectionality of transgender human rights, Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli said:

“I don’t think LGBT rights or transgender rights exist in isolation, they are part of a larger gamut of climate change, racial equality, gender equality, the elimination of plastics, and all of that.”

The panelists had different opinions on whether it is enough to rely on the law for the recognition and protection of the human rights of transgender individuals.

The common denominator, however, was that the laws as they stand have a long way to go before fully giving effect to the right of equality before the law and equal protection of the law without discrimination of transgender people.

Tshepo Ricki Kgositau-Kanza, who was a litigant in a landmark case in Botswana in which the judiciary upheld the right of transgender persons to have their gender marker changed on national identity documents, explained the challenges with policies which, on their face, seem uniform:

“Uniform policies… are very violent experiences for transgender persons in a Botswana context where the uniform application of laws and policies is binary and arbitrarily assigned based on one’s sex marker on one’s identity document which reflects them either as male or female. Anybody in between or outside of that kind of dichotomy is often rendered invisible and vulnerable to a system that can easily abuse them.”

This conversation can be viewed here.

Contact

Tanveer Jeewa, Communications Officer, African Regional Programme, e: tanveer.jeewa(a)icj.org

Oct 26, 2020 | News

The ICJ and Lawyers Alert today called on the Nigerian authorities to undertake immediate independent and thorough investigations into credible allegations of extrajudicial killings by the military responding to mass protests against the SARS police unit.

Those responsible for criminal conduct must be brought to justice and held to account, the two organizations said.

The authorities must respect their international legal obligations under international law and cease the unlawful, unnecessary and disproportionate use of force in response to Nigerians’ lawful protest actions.

Protest actions have escalated over the last two weeks as Nigerians have staged a series of protests under the #EndSARS movement. Thousands of people joined the demonstrations, demanding an end to police brutality and corruption.

Reports confirm that more than 56 people have died over the two weeks of protest actions, including 38 protesters who were killed, on the 20 October alone, as a result of the Nigerian military opening fire on thousands of peaceful protesters.

“The right to peaceful assembly is guaranteed under international law, including the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) which Nigeria has acceded to. Nigeria’s brutal responses to the peaceful demonstrations, including the use of lethal force on force protestors, not only violates this right but also their right to life,” said Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh, ICJ Africa Regional Programme Director.

Lawyers Alert Executive Director Rommy Mom said: “The Nigerian government’s responses to the protests have undermined the rule of law. Groups and persons should not be afraid to approach the Judicial Panels of Inquiry to lay their grievance towards identification of culpable SARS officers for appropriate sanctions and the compensation of victims.” The organizations recall that under international law, the use of lethal force by law enforcement officials is permissible only when strictly necessary to protect life.

Police in the SARS unit are credibly alleged to be responsible for a widespread practice of torture and other serious human rights violations.

In addition to ending these violent attacks on protestors, the ICJ and Lawyers Alert call on the Nigerian government to address the demands of protestors and embark on comprehensive reform of the police, with emphasis on oversight functions, tethering oversight to civil society groups, the National Human Rights Commission and the constitutional oversight body of the Nigeria police.

“These protests have gained momentum outside Nigeria and have extended beyond the local borders to Ghana, United Kingdom and South Africa. The world’s attention is currently on Nigeria, as the global support for protestors rise amidst further police brutality. The Nigerian government must ensure that it respects and protects the human rights of all in accordance with its obligations under international law,” added Ramjathan-Keogh.

Background

Founded in 1992, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) was mandated to “investigate cases involving armed robbery and kidnapping”. However, since its inception, there have been widespread complaints by Nigerians about the conduct of SARS This year Amnesty International issued a report, documenting at least 82 cases of torture, ill treatment and extra-judicial execution by SARS during the period of January 2017 and May 2020

In addition to the ICCPR, Nigeria is party to the UN Convention against Torture and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter), which guarantees the right to life under Article 4 and the right to assemble freely with others under Article 11. These rights are also respectively protected under sections 33(1) and 40 of the Nigerian Constitution.

Article 6 of the ICCPR prohibits the arbitrary deprivation of life.

Principle 9 of the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials affirm that:

Law enforcement officials shall not use firearms against persons except in self-defence or defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury, to prevent the perpetration of a particularly serious crime involving grave threat to life, to arrest a person presenting such a danger and resisting their authority, or to prevent his or her escape, and only when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve these objectives. In any event, intentional lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.

Contact

Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh, Director of ICJ’s Africa Regional Programme, c: +27845148039, e: kaajal.keogh(a)icj.org

Tanveer Jeewa, Communications Officer, tanveer.jeewa(a)icj.org

Homepage photo credit: Tshwanelo Mathwai