Oct 10, 2017 | Multimedia items, News, Video clips

Selected by a jury of 10 global human rights organizations, including the ICJ, Mohamed Zaree is a devoted human rights activist and legal scholar whose work focuses on human rights advocacy around freedom of expression and association.

Mohamed Zaree is also known for his role as the Egypt Country Director of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS), which works throughout the Arabic speaking world.

He assumed this role after government pressure on CIHRS prompted them to relocate their headquarters to Tunis in 2014.

The Egyptian government has been escalating its pressure on the human rights movement.

Human rights NGOs and defenders are confronted with a growing wave of threats, harassment, and intimidation, legal and otherwise.

Despite this, Mohamed Zaree is leading CIHRS’ research, human rights education, and national advocacy initiatives in Egypt and is shaping the media debate on human rights issues.

During this critical period for civil society, he is also leading the Forum of Independent Egyptian Human Rights NGOs, a network aiming to unify human rights groups in advocacy.

Zaree’s initiatives have helped NGOs to develop common approaches to human rights issues in Egypt.

Within the context of the renewed crackdown on Egyptian human rights organizations, he has become a leading figure in Egypt’s human rights movement.

He is currently facing investigation under the “Foreign Funding Case” and is at high risk of prosecution and life imprisonment. The “Foreign Funding Case” highly restricts NGO activities.

Despite this, Mohammed Zaree continues to engage the authorities in dialogue wherever possible, arguing that respect for human rights will increase stability in Egypt.

He has been under a travel ban since May 2016 but remains present and active in Egypt and represents CIHRS inside the country.

“Mohamed Zaree is a leading voice for justice in Egypt. Honoring him with the Martin Ennals Award is a recognition of the courageous and tireless work done by Egyptian human rights defenders, individuals and NGOs, in their fight against all forms of intimidation, harassment and repression waged by the Egyptian military and government against them,” said Said Benarbia, Director of the ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme.

FreeThe5KH (Cambodia) and Karla Avelar, the two other finalists, received Martin Ennals Prizes.

FreeThe5KH are five Human Rights Defenders who were recently released after 427 days of pre-trial detention.

They are awaiting trial and are banned from travel.

There were widespread international calls for their unconditional release, and a stop to judicial harassment of human rights defenders in Cambodia.

This comes in the context of an increasingly severe crackdown on civil society and the political opposition in Cambodia.

Karla Avelar, a transgender woman in El Salvador, founded the country’s first organization of transgender women – COMCAVIS TRANS.

She grew up on the streets, suffering discrimination, violence, sexual exploitation, rape, and attempted murder.

She works to change national legislation and the authorities’ practices, by publicizing violations suffered by LGBTI people.

Her advocacy helped prompt the authorities to segregate LGBTI prisoners for their own safety, and provide HIV treatment.

Background

The “Nobel Prize of Human Rights”, the Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders (MEA) is a unique collaboration among ten of the world’s leading human rights organizations to give protection to human rights defenders worldwide.

Strongly supported by the City of Geneva, the award is given to Human Rights Defenders who have shown deep commitment and face great personal risk.

Its aim is to provide protection through international recognition.

The Jury is composed of the following NGOs: ICJ, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Human Rights First, Int’l Federation for Human Rights, World Organisation Against Torture, Front Line Defenders, EWDE Germany, International Service for Human Rights, and HURIDOCS.

Contact:

Michael Khambatta, Director, Martin Ennals Foundation, t: +41 79 474 8208, e: khambatta(a)martinennalsaward.org

Olivier van Bogaert, Director, ICJ Media and Communications, and ICJ Representative on the MEA Jury, t: +41 22 979 38 08, e: olivier.vanbogaert(a)icj.org

The Award will be presented by the United Nations Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights at 18.15 on 10 October at the University of Geneva. The ceremony can be watched live on Martin Ennals Award Facebook page

Watch the movie on Mohammed Zaree

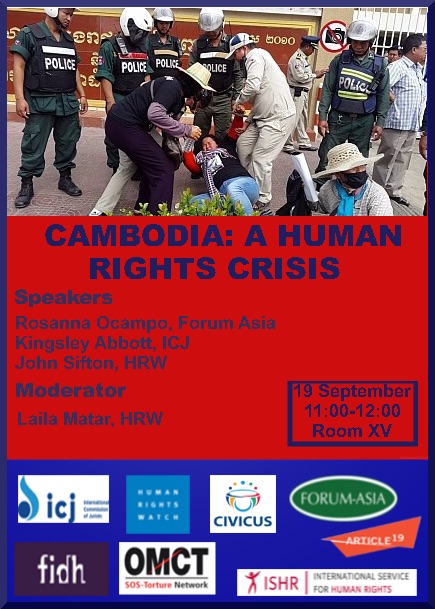

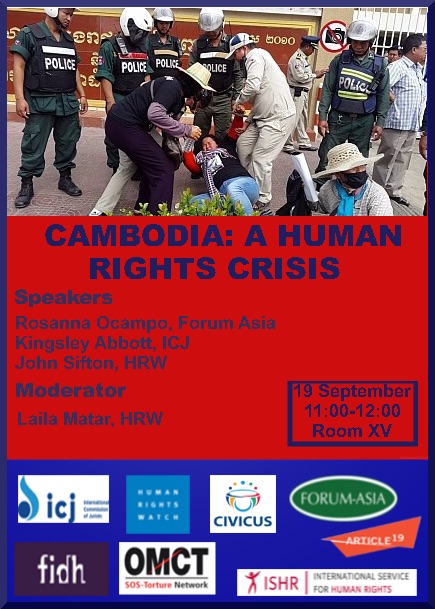

Sep 18, 2017 | Events

On 19 September, the ICJ and other leading international NGOs are convening a panel to discuss the crisis for human rights and rule of law in Cambodia, at a side event to the UN Human Rights Council session taking place in Geneva.

The side event comes as States consider a new draft resolution on Cambodia for adoption by the Human Rights Council. Before the session, the ICJ joined other organizations in calling for strengthening of the resolution and its measures for monitoring, reporting on and discussing the situation for human rights in the country.

Moderator:

- Laila Matar, Senior UN Advocate, Human Rights Watch

Speakers:

- Rosanna Ocampo, Forum Asia

- Kingsley Abbott, International Commission of Jurists

- John Sifton, Human Rights Watch

The event takes place Tuesday, 19 September 2017, 11:00 – 12:00, in the Palais des Nations, Room XV.

ICJ is organizing the event together with Human Rights Watch, Forum-Asia, Civicus, Article 19, FIDH, OMCT, and ISHR.

For more information, contact un(a)icj.org

Sep 11, 2017 | News

The Government of Myanmar must do everything in its power to respect and protect human rights during military operations in northern Rakhine State, said the ICJ today.

These military operations have reportedly resulted in widespread unlawful killing and the displacement of more than 200,000 people in response to attacks attributed to ARSA.

The ICJ called on Myanmar’s government to act as swiftly as possible to address the root causes of violence, discrimination and under-development in Rakhine, as well as for enhanced engagement by the international community in efforts to effectively address the situation, and to take measures to ensure that security operations are conducted in accordance with international human rights standards.

The military operations follow attacks by ARSA on August 25 on police posts and a military base in which at least 12 police, military and government officials were killed, along with a large number of attackers (according to government figures).

In the wake of the attacks on 25 August, the military launched what it has termed as a “clearance operation,” and the government announced that parts of northern Rakhine State have been designated as a “military operations area.”

“The attacks attributed to ARSA constitute serious crimes for which individual perpetrators should be brought to account through fair trials conducted in accordance with international standards,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Secretary General.

“But ‘clearance operations’ carried out by the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military) in an unlawful manner, and allegations of serious human rights violations, many amounting to crimes under international law, are on an entirely different scale and cannot be justified in the name of security or countering terrorism. These allegations must be promptly investigated in light of the Tatmadaw’s decades-long record of grave human rights violations and impunity throughout Myanmar,” he added.

“The Tatmadaw is responsible for the conduct of security operations in Rakhine as in other parts of the country, but the entire government remains responsible for upholding its international legal obligations to protect the rights of everyone living in Rakhine State – including the Rohingya Muslim communities that constitute the overwhelming majority of the population in the areas most affected by the violence,” Zarifi said.

“We also urge the State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi to use her immense electoral popularity and moral stature to push for full respect for human rights for the Rohingya as well as all others in Rakhine State.”

In the wake of the attacks on 25 August, the military launched what it has termed as a “clearance operation,” and the government announced that parts of northern Rakhine State have been designated as a “military operations area.”

These terms are not clearly prescribed in Myanmar’s laws, but in practice seem to be used to grant the military authority to ignore legal protections afforded under the country’s constitution and international standards.

“Whatever descriptive cover may be used to describe security operations, they must scrupulously respect international standards on the use of force.” Zarifi said.

“Myanmar’s government has the right, indeed the obligation, to protect all people in its jurisdiction from attacks by armed groups, but it must do so in conformity with international law. Experience from around the world has shown that greater respect for rule of law and human rights is the most effective response to terrorism,” he added.

This was unfortunately not the case following the arrests and detentions carried out during the military operations that followed attacks in October 2016.

Many of these arrests appear arbitrary and unlawful, as detainees were not given access to legal counsel, and deaths in custody have not been properly investigated.

Similar violations by the military have been documented recently in Shan and Kachin States.

Government authorities must ensure that arrest and detention in the context of the current operations in Rakhine State be conducted in accordance with national and international law, and respect the rights to liberty, freedom from arbitrary detention and a fair trial.

The most effective way for the government to respond to allegations of abuse by the security forces both in Rakhine and elsewhere in the country would be to take well-founded allegations seriously, and ensure that they are promptly, impartially and thoroughly investigated and those responsibility are brought to justice.

It is an unfortunate fact that investigations and prosecutions of human rights violations are rarely undertaken in regular courts, as national laws shield security forces from public criminal prosecutions, often by using military or special police courts.

Zarifi further said: “Ending the military’s impunity would establish much needed confidence in the government’s commitment to upholding the rule of law.”

“One immediate way to illustrate this commitment would be to cooperate with the UN Fact Finding Mission, which the ICJ and other organizations called for earlier in the year, to investigate allegations of human rights violations and abuses in Myanmar.”

“There are paths forward for the government to both respond to allegations of rights violations, and to show its commitment to finding solutions to the unacceptable state of affairs in Rakhine State.”

Myanmar-RakhineStateCrisis-PressReleases-2017-ENG (full press release)

Sep 3, 2017 | News

On 2 and 3 September, the ICJ held a workshop on “the Rule of Law and Strengthening the Administration of Justice in the Context of Restorative Justice” for members of the Thai judiciary.

The workshop was held in Chiang Mai.

Twenty-two judges attended the workshop, with an observer from the Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ).

The objective of the workshop was to discuss how to best apply international standards of restorative justice within Thailand’s justice system.

Restorative justice is based on the fundamental principle that criminal behavior not only violates the law, but also injures victims and the community.

A restorative process is any process in which the victim and the offender and, where appropriate, any other individuals or community members affected by a crime participate together actively in the resolution of matters arising from the crime, with the help of a facilitator.

Frederick Rawski, Regional Director of ICJ Asia and the Pacific, recognized in his opening statement that implementation of restorative justice, including constructive non-custodial sentencing and measures, could assist in combating the problem of overcrowding in detention facilities in the North of Thailand, particularly with respect to drug-dependent offenders.

The workshop made reference to the United Nations Declaration of Basic Principles on the Use of Restorative Justice Programmes in Criminal Matters, which was adopted by the United Nations Economic and Social Council in 2002.

Speakers at the Workshop included Chief Justice Somnuk Panich from Office of the Chief Justice Region V, who formally opened the workshop, Judge Dr. Dol Bunnag, Presiding Judge of Intellectual Property and International Trade Court, who summarized the landscape of restorative justice in Thailand, and Judge Sir David James Carruthers from New Zealand, an international expert on restorative justice in New Zealand.

ICJ’s Senior International Legal Adviser Kingsley Abbott moderated the two-day workshop.

The ICJ ended the workshop with a statement reiterating its commitment towards working with Thailand’s judiciary to strengthen the rule of law and administration of justice in Thailand.

Sep 1, 2017 | News

On 1 September, the ICJ, in collaboration with Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Law and Chiang Mai University’s Center for Ethnic Studies and Development under its Faculty of Social Science, conducted a workshop on how effectively to conduct trial observation.

Participants in the Workshop included undergraduate and postgraduate students and lecturers from Chiang Mai University, lawyers and representatives from Thai civil society organizations.

The workshop was held at Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Law campus.

The objective of the workshop was to provide participants with an overview of international law and standards governing right to a fair trial and due process in the administration of criminal justice.

The workshop used the ICJ’s Practitioners Guide No. 5, the Trial Observation Manual for Criminal Proceedings, as the basis of training.

The workshop trained participants on practical preparation techniques before undertaking trial observations, critical elements of trial observations, drafting of trial observation reports, general international legal standards governing fair trials, international legal standards applicable to arrest and pre-trial detention in criminal proceedings and international legal standards applicable to trial proceedings.

The speakers at the workshop were Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser, Southeast Asia and Sanhawan Srisod, ICJ Associate National Legal Adviser, Thailand.

Aug 30, 2017 | News

On 30 August, the ICJ co-hosted an event in Bangkok, Thailand, named “International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearance: Human Rights Defenders & the Disappeared Justice”.

The event began with opening remarks by South-East Asia’s Regional Representative of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Cynthia Veliko.

Thereafter, Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser, spoke in a panel discussion about enforced disappearances in Thailand, highlighting the need for Thailand to comply with its human rights obligations under international law.

This panel discussion also included Ms. Oranuch Phonpinyo, Community Representative, forensics expert Dr. Pornthip Rojanasunan and former National Human Rights Commissioner Dr. Niran Pitakwatchara.

In a second panel discussion held during the event, speakers included Ms. Phinnapha Phrueksaphan, Victim Representative, Ms. Angkhana Neelapaijit, National Human Rights Commissioner and Victim Representative, Ms. Nareeluc Pairchaiyapoom from Thailand’s Ministry of Justice and prominent human rights lawyer Mr. Somchai Homlaor.

The event focused on the lack of progress in Thailand with regard to investigating cases of apparent enforced disappearance and called for the Royal Thai government to amend and pass legislation criminalizing torture, ill-treatment and enforced disappearance without further delay.

Thailand is a State party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) and has signed, but not yet ratified, the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED).

The other organizers of the event were OHCHR’s South-East Asia Regional Office, the Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF), Human Rights Lawyers Association (HRLA), the Esaan Land Reform Network, Amnesty International Thailand, Thailand’s Ministry of Justice and the Association for the Prevention of Torture (APT).

Copies of an open letter sent by the ICJ and other human rights groups to the Royal Thai government on 30 August were distributed to the event’s participants.

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

See the full open letter here in English and Thai

Read also

Ten Years Without Truth: Somchai Neelapaijit and Enforced Disappearances in Thailand