May 7, 2021 | News

As the European Union and India prepare for a meeting of their leaders on 8 May they should jointly commit to a strategy for protecting all people in India from the devastating second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic now ravaging the country, said the ICJ today.

India has faced unprecedented impact from the pandemic since 15 April, with some 400,000 daily cases and a daily death toll now officially around 4,000 and likely even higher. India’s healthcare system and infrastructure has strained to meet the needs of people for oxygen, medicines, testing, hospital beds, ambulances, and doctors. India, a vaccine-production powerhouse globally, has only vaccinated just over two percent of its population and is now facing severe shortage of vaccines.

“The scenes emerging from India are horrifying but unfortunately not unexpected. This global pandemic demands global cooperation and national competence and this is the moment for the EU and India to demonstrate cooperation and competence. The Indian government was lecturing the world about its performance instead of preparing for the predictable resurgence of the pandemic, and now it is busy silencing people demanding help or criticizing the government’s poor performance,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Secretary-General.

The ICJ added that the performance of the EU and its Member States in international cooperation to tackle COVID globally left much to be desired, particularly as they have resisted supporting a loosening of intellectual property restrictions that have hampered efforts at wider vaccine production and distribution.

“At the same time, the proposal by India and South Africa for removing global patent restrictions for vaccine protection was rejected by some of the wealthiest governments, including the EU, who seem more focused on economic interests rather than global responses to a global pandemic,” said Zarifi.

The EU has already agreed to assistance to India through its Civil Protection Mechanism and individual EU countries have delivered some needed supplies and vaccines.

“The EU and Member States should increase aid efforts to India and immediately reverse their opposition to waiving intellectual property restrictions to vaccine production under the World Trade Organization TRIPS agreement, especially now that the United States has indicated it would end its obstructionism. The EU should not be on the wrong side of history as the last obstacle to global vaccine production,” Zarifi said.

The ICJ also urged the EU to remind the Indian government of its obligations under international law and guarantees of the Indian Constitution to protect the rights of people in India to life and to health.

“The summit between the European Union and India brings together powerful States who should use this opportunity to align their actions at the global, regional, and national levels to protect people from the pandemic,” said Zarifi. “International law provides the framework for cooperation and both the EU and India must do a better job of complying with their international legal obligations.”

Additional Information

India’s judiciary has at various levels has severely criticized the Indian Central and State governments and issued orders for urgent remedial responses.

In particular, the Indian Supreme Court has ordered the central government to:

- ensure adequate supply of oxygen through provision of emergency buffer stock by the central government in collaboration with state governments;

- develop a national policy on admission to hospitals and in the interim ensure that no patient is denied access to hospitals or essential drugs; and

- recognize vaccines as a “valuable public good”.

The Supreme Court has also questioned the constitutionality of India’s vaccine policy due to differential pricing for state governments, the central government and private hospitals, stating that the government needs to revisit the policy so that it “withstands the scrutiny of Articles 14[right to equality] and Article 21[right to life] of the Constitution”.

Additionally, the Supreme Court has suggested that the Central Government take steps to ensure access to essential drugs as well as to enhance its healthcare workforce as needed, in line with India’s constitution and its international legal obligations.

As party to the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, India is required to take all necessary measures to ensure the “prevention, treatment and control of epidemic” and to create conditions “which would assure to all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness”. Further, these obligations, as stressed by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights entail removing any discrimination in vaccine access; guaranteeing affordability and economic accessibility of vaccines for all people; prioritizing physical accessibility to vaccines, especially for marginalized groups and people living in remote areas; and guaranteeing access to relevant health information.

Additional Reading

EU: prioritize rights at India Summit, provide essential medical supplies, urge India to free rights defenders, address abuses – ICJ Press Release, 3 May 2021

Indian Government Fails to Protect Right to Life and Health in Second Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic – ICJ Press Release, 29 April 2021

Contact

Osama Motiwala, ICJ Asia-Pacific Communications Officer, t: +66-62-702-6369; e: osama.motiwala(a)icj.org

May 3, 2021 | News

European leaders at the May 8, 2021 summit with their Indian counterparts should prioritize the deteriorating human rights situation in India, including the right to health, the ICJ and seven other organizations said today.

With a devastating Covid-19 crisis affecting the country, Europe should focus on providing support to help India deal with the acute shortage of medical supplies and access to vaccines. At the same time, European leaders should press the Indian government to reverse its abusive and discriminatory policies and immediately release all human rights defenders and other critics who have been jailed for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.

The organizations are Amnesty International, Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), Front Line Defenders (FLD), Human Rights Watch, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN, International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), and World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT).

India has the fastest-growing number of Covid-19 cases in the world and is facing severe healthcare shortages – of testing capacity, medicines, ambulance services, hospital beds, oxygen support, and vaccines. The European Union and its member states should reconsider and reverse their opposition to India and South Africa’s proposal before the World Trade Organization to temporarily waive certain intellectual property rules under the TRIPS Agreement to facilitate increased manufacturing and production of vaccines and related products globally, until widespread vaccination is in place the world over.

The Covid-19 crisis has also highlighted growing human rights concerns in India.. Faced with widespread criticism of its handling of the pandemic, the Indian government has tried to censor free speech, including by ordering social media content taken down and criminalizing calls for help. The government has also ignored calls from the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights for countries to release “every person detained without sufficient legal basis, including political prisoners, and those detained for critical, dissenting views” to prevent the growing rates of infection everywhere, including in closed facilities such as prisons and detention centers.

Instead, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government has increasingly harassed, intimidated and arbitrarily arrested human rights defenders, journalists, peaceful protesters, and other critics, including under draconian sedition and counterterrorism laws.

The authorities have jailed a number of human rights defenders, student activists, academics, opposition leaders, and critics, blaming them for the communal violence in February 2020 in Delhi as well as caste-based violence in Bhima Koregaon in Maharashtra state in January 2018. In both cases, BJP supporters were implicated in the violence. Police investigations in these cases were biased and aimed at silencing dissent and deterring future protests against government policies, the groups said.

The government uses foreign funding laws and other regulations to crack down on civil society. Recent amendments to the Foreign Contributions Regulations Act (FCRA) added onerous governmental oversight, additional regulations and certification processes, and operational requirements, which adversely affect civil society groups, and effectively restrict access to foreign funding for small nongovernmental organizations. In September 2020, Amnesty International India was forced to halt its work in the country after the Indian government froze its bank accounts in reprisal for the organization’s human rights work, and many other local rights groups struggle to continue doing their work.

The Indian authorities have also enacted discriminatory laws and policies against minorities. Muslim and Dalit communities face growing attacks, while authorities fail to take action against BJP leaders who vilify minority communities, and against BJP supporters who engage in violence. The Indian government has imposed harsh and discriminatory restrictions on Muslim-majority areas in Jammu and Kashmir since revoking the state’s constitutional status in August 2019 and splitting it into two federally governed territories.

The authorities carried out counterterrorism raids in October on multiple nongovernmental organizations in Kashmir and Delhi, and a newspaper office in Srinagar to silence them, causing a chilling effect on human rights defenders who fear for their safety.

Yet, despite the considerable deterioration in the country’s human rights record under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the Indian government has effectively shielded itself from the international scrutiny and reactions that the seriousness of the situation should have warranted. Focusing on strengthening trade and economic ties with India, the European Union and its member states have been reluctant to formulate public expressions of concern on human rights in India, with the exception of occasional statements focused solely on the death penalty.

To read the full statement, click here.

Contact:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Secretary General, t: +66 627026369, e: sam.zarifi(a)icj.org

Apr 29, 2021 | News

The Indian Government must urgently remedy failures that have aggravated the impact of the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic and led to people in the country suffering record-high rates of infection and death, said the ICJ today.

The ICJ urged India’s central and state governments to comply with judicial orders regarding guaranteeing access to adequate, timely and nominally priced oxygen supply, hospital beds, COVID-19 medicines, COVID-19 tests and vaccines, in line with India’s constitutional and international legal obligations.

“The Indian federal and state governments failed to prepare for the predictable second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, aggravating the horrific impact of the pandemic and the avoidable tragedy of between 1,500 to over 3,000 deaths daily,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Secretary General.

Since 15 April India has reported more than 200,000 cases per day and on 27 April, it reported 360,960 – the highest globally – in a devastating second wave, with the official number of deaths hovering at over 1,500 – 3,000 per day, and feared to be higher actually.

Many hospitals have reportedly turned away patients due to lack of space and some hospitals have reportedly asked those they admit to sign forms accepting the risk in case of death caused by exhaustion of oxygen supply.

The government’s failures have driven people to seek recourse in the courts. At least 11 High Courts across the country have taken cognizance of the crisis and have passed orders regarding matters including access to oxygen supply and oxygen tankers, access to medicines such as Remdesivir and to hospital beds; restriction on black marketing and private hoarding of medicines and oxygen; and prevention of violations of COVID19 regulations relating to mask wearing and social distancing.

Courts have also ordered that accurate data on COVID19 cases and deaths be relayed by the state government. The Indian Supreme Court also took suo moto cognizance of the issue and has called for a report from the central government on issues related to supply of oxygen, essential drugs, vaccine pricing.

The Delhi High Court on 21 April asked the central government to ensure that “the emergent needs of various hospitals in Delhi… would be met so that no causalities are suffered on account of discontinuing the supply of Oxygen to seriously ill COVID patients.” On 27 April, the Delhi High Court asked the Delhi government to ensure transparency in accounting of supply of oxygen and drugs to prevent hoarding and black-marketing.

The Bombay High Court on 22 April gave directions to ensure uninterrupted oxygen supply to city hospitals, access to medicines and beds, and tests.

“While the ICJ commends the Indian judiciary in trying to respond to this crisis urgently, the fact remains that a lack of a national public health strategy by the Indian Government has resulted in acute shortages of essential drugs, oxygen, and hospital beds in places where they are needed,” said Zarifi.

India is obligated under Article 12, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), to guarantee the right to health. Under Article 12(c), ICESCR, the Indian State is required to prevent, treat and control all diseases including epidemic diseases such as COVID-19. Moreover, Article 12(d), ICESCR, requires India to create conditions that allow for “medical service and medical attention” to all in the event of a sickness, such as COVID-19. The minimum core obligations under Article 12, ICESCR, include, among others, provision of essential drugs, and a national public health strategy and a plan of action on the basis of epidemiological evidence, addressing the health concerns of the whole population. The Indian State has failed egregiously in meeting its minimum core obligations under the right to health.

The ICJ recommends, in line with decisions of Indian courts, that the Indian federal government work effectively with various state governments and other entities to remove bottlenecks in supply of medicines and oxygen, and set up additional facilities for COVID19 patients. The Indian government must also promote and model COVID appropriate behavior such as masking and social distancing and begin preparing for any subsequent waves of the pandemic.

Contact

Maitreyi Gupta, ICJ India Legal Adviser, t: +91 77 560 28369 e: maitreyi.gupta(a)icj.org

Feb 11, 2021 | News

The ICJ today condemned the unlawful repression of peaceful protests and urged the Indian authorities to respect the right to freedom of assembly of Indian farmers who have been demonstrating in Delhi since November 26, 2020 against newly promulgated agricultural laws.

Since early February 2021, police have used metal barricades, cement walls and iron nails to block the roads leading to Tikri, Singhu, Ghazipur, the three main borders where the farmers have assembled. They have done so to prevent any vehicles from these areas entering Delhi. The barricades have also served to deny male and female farmers and their families, including children, consistent access to water and sanitation facilities. The protests at these sites over the past two months are reported to have been peaceful.

Thousands of farmers from all over India, and most heavily from Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, have demanded the repeal of a new set of agricultural laws, fearing that these will serve to eliminate government protections for crop prices and thereby impact their livelihoods.

Two journalists were detained and assaulted for reporting from the ground, while nine senior journalists have been threatened with criminal charges including sedition charges by the Indian Government. More than 125 persons, including farmers and also bystanders have reportedly been arrested largely in response to a violent clash that occurred on 26 January 2021. At least 21 farmers are reported to be currently missing.

“Rather than protecting the right to peaceful protest as required by law, the Indian authorities have cracked down on farmers in an arbitrary and aggressive manner, using unlawful force and preventing free movement as well as access to essential facilities”, said Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director.

The Indian Supreme Court on 17 December 2020, upheld the right to protest of farmers calling it “part of a fundamental right” which can be exercised “subject to public order”. The Court has further said that “[t]here can certainly be no impediment in the exercise of such rights as long as it is non-violent and does not result in damage to the life and properties of other citizens and is in accordance with law.”

“The suppression of the right to peaceful assembly has become a pattern in India, as we saw in December 2019 and January 2020 with the mass arrests of students and human rights defenders who were protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act,” said Seiderman.

The ICJ called on the responsible authorities to remove barricades around protest sites, enable access to water and sanitation facilities and to desist from further arbitrary arrests.

Background

The three contentious farm laws being the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 and Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 were brought in through executive ordinance without legislative consultation and adequate scrutiny and received presidential assent on 27 September 2020.

Farmer unions from Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh began to set up protest sites on the borders of Delhi on 26 November 2020. There have been a series of unsuccessful negotiations between the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare and the farmer representatives. In response to the protests, the Indian Supreme Court on 12 January ordered the suspension of the “implementation of the three farm laws until further orders”. The Court set up a four-person expert committee to negotiate between farmers and the Government. However the committee’s efforts have become stalled.

On 26 January, India’s Republic Day, some tens of thousands of farmers drove into Delhi in tractors, with some protestors deviating from the sanctioned routes permitted by the Delhi Police. There were clashes with the police where one protestor was killed in the violence, and nearly 400 policemen were injured. Some protestors also entered the Red Fort, an historical monument, and hoisted the Sikh religious flag on a flagpole.

On 29 January, police and at least some private forces tried to forcibly disperse the protests on Ghazipur, Singhu and Tikri borders through stone pelting and baton charging. Farmer protestors allege that the some of those working with the police were associated with Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangathan (RSS), the ideological outfit associated with the ruling party Bhartiya Janata Party.

On 6 February there was a three-hour blockade on state and national highways placed by farmers throughout large parts of India in protest against the agricultural laws, the government’s measures against the protestors and the reduction of budgetary allocation for farmers.

Freedom of assembly is protected under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which India is a party.

Contact

Maitreyi Gupta, ICJ India Legal Adviser, t: +91 77 560 28369 e: maitreyi.gupta(a)icj.org

Nov 19, 2020 | News

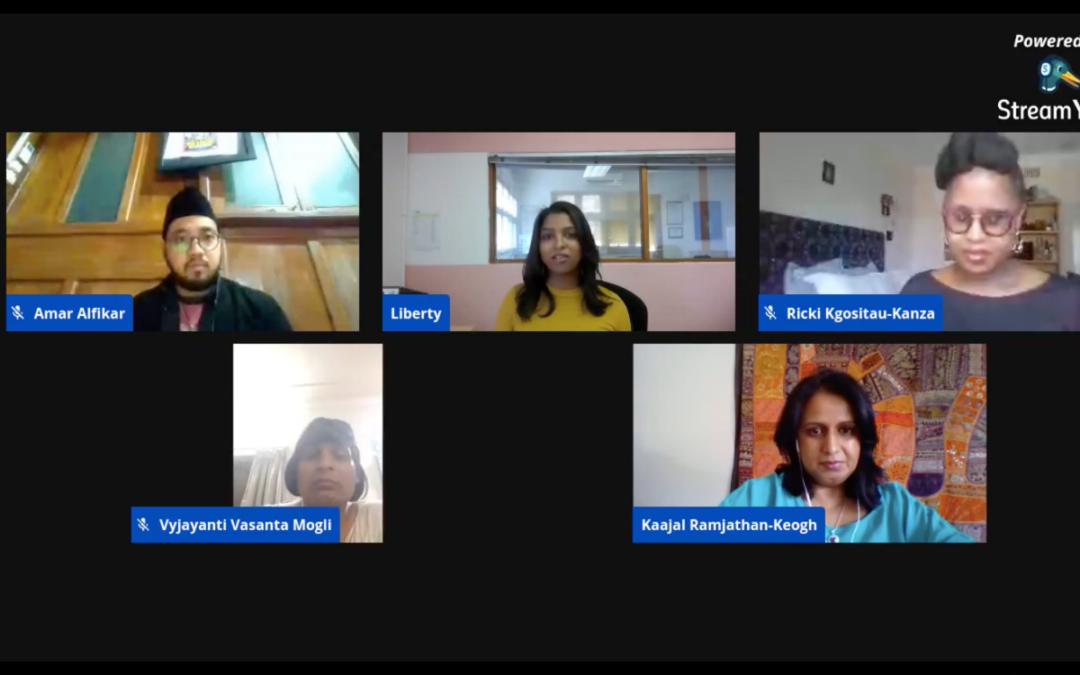

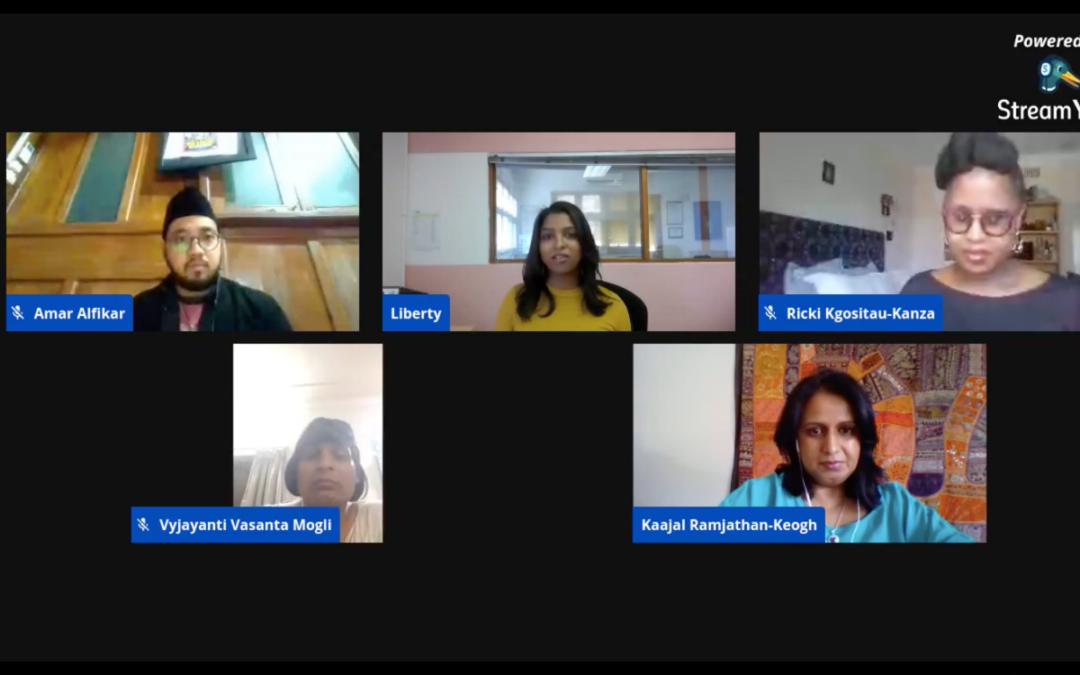

On 18 November 2020, the ICJ hosted a Facebook Live with four transgender human rights activists from Asia and Africa. It highlighted the stark reality between progressive laws and violent lived realities of transgender people.

The 20th November 2020 marks the Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR), the day when transgender and gender diverse people who have lost their lives to hate crime, transphobia and targeted violence are remembered, commemorated and memorialized.

The discussions focused on their individual experiences of Transgender Day of Remembrance in their local contexts, the impact of COVID-19 on transgender communities and whether laws are enough to protect and enforce the human rights of transgender and gender diverse people.

The renowned panelists were from four different countries, Amar Alfikar from Indonesia, Liberty Matthyse from South Africa, Tshepo Ricki Kgositau-Kanza from Botswana and Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli from India. The panel was moderated by the ICJ Africa Regional Director, Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh.

The panel aimed to provide quick glimpses into different regional contexts and a platform for transgender human rights activists’ voices on the meaning of Transgender Day of Remembrance and the varied and devastating impacts of COVID-19 on transgender people.

The speakers discussed the meaning that they individually ascribe to Transgender Day of Remembrance. A common theme running across the conversations was that it is not enough to highlight issues and concerns of the transgender community only on this day. Instead, these discussions should be part of daily conversations about the human rights of transgender people at the local and international level.

Liberty Matthyse discussed the importance of remembering the transgender persons who have lost their lives over the past years, and added:

“South Africa generally is known as a country which has become quite friendly to LGBTI people more broadly and this, of course, stands in stark contradiction to the lived realities of people on the ground as we navigate a society that is excessively violent towards transgender persons and gay people more broadly.”

Amar Alfikar describes his work as “Queering Faiths in Indonesia”. This informs his understanding of what Transgender Day of Remembrance means in his country and he believes that:

“Religion should be a source of humanity and justice. It should be a space where people are safe, not the opposite. When the community and society do not accept queer people, religion should start giving the message, shifting the way of thinking and the way of narrating, to be more accepting, to be more embracing.”

It was clear from the discussions that a lot of the issues that have become prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic, have not arisen due to the pandemic. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has had the effect of a magnifying glass, amplifying existing challenges in the way that transgender communities are treated and driven to margins of society. Speaking about the intersectionality of transgender human rights, Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli said:

“I don’t think LGBT rights or transgender rights exist in isolation, they are part of a larger gamut of climate change, racial equality, gender equality, the elimination of plastics, and all of that.”

The panelists had different opinions on whether it is enough to rely on the law for the recognition and protection of the human rights of transgender individuals.

The common denominator, however, was that the laws as they stand have a long way to go before fully giving effect to the right of equality before the law and equal protection of the law without discrimination of transgender people.

Tshepo Ricki Kgositau-Kanza, who was a litigant in a landmark case in Botswana in which the judiciary upheld the right of transgender persons to have their gender marker changed on national identity documents, explained the challenges with policies which, on their face, seem uniform:

“Uniform policies… are very violent experiences for transgender persons in a Botswana context where the uniform application of laws and policies is binary and arbitrarily assigned based on one’s sex marker on one’s identity document which reflects them either as male or female. Anybody in between or outside of that kind of dichotomy is often rendered invisible and vulnerable to a system that can easily abuse them.”

This conversation can be viewed here.

Contact

Tanveer Jeewa, Communications Officer, African Regional Programme, e: tanveer.jeewa(a)icj.org