Dec 10, 2018 | Multimedia items, News, Video clips

Today, 10 December 2018 marks the 70th anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Developed as a universal standard setting out the rights to be enjoyed by everyone, the elaboration of the UDHR was one of the first actions undertaken by the newly established UN in carrying out its human rights mandate.

The UN Charter, forged after the ravages of the Second World War, places advancement of human rights as a core purpose and principle of the UN.

Over the past 70 years, the UN and regional human rights systems have taken the UDHR as the benchmark in developing the impressive normative architecture that constitutes the present day basis of international human rights law and standards.

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) was founded in 1952, only four years after the UDHR, with a mission to advance the rule of law and legal protection of human rights. Most of the international legal human framework at that time had still not yet been developed. The founding members of the ICJ believed that the lofty human rights principles enunciated in the UDHR needed to be transformed into hard and enforceable legal obligations incumbent on all States. From its founding, the ICJ worked to develop treaties and other standards aimed to make the enjoyment of human rights real for people, and not merely aspirational.

According to Sam Zarifi, Secretary General of the ICJ, “The ICJ’s biggest contribution to the international legal framework is still to bring together jurists from around the world to defend the rule of law and the universality of human rights at the global and local level.”

“Many now established global legal instruments have the fingerprints of the ICJ all over them. Crucial regional frameworks in the African, European, and American regions were developed with the deep and sustained involvement of the ICJ, as were the creation of the post of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the International Criminal Court,” said Sam Zarifi.

The UDHR has not only inspired the work of human rights defenders, but has also been foundational for the general acceptance of the notion of human rights around the world.

From 1948 until the end of the twentieth century, there has generally been a continuous upward trajectory towards the advancement of human rights, even if there have been many pitfalls along the way.

The notion that people have rights is now universally accepted and known by people. At the Vienna Conference on Human Rights in 1993, all States of the world not only reaffirmed their commitment to the UDHR, but also agreed that “the universal nature of these rights and freedoms is beyond question.”

Over the years, there have certainly been major shortcomings in the push to achieve the realization of the human rights for all.

Some of the extreme examples include armed conflicts replete with crimes against humanity, war crimes and even genocide, followed by a failure to hold perpetrators accountable.

And there remains extreme poverty in parts of the world marked by a thorough neglect of economic and social rights.

Despite these shortfalls in implementation, it remains the case that human rights have been accepted as a key component in addressing humanity’s problems in the 70 years since the adoption of the UDHR.

“Over the years, more and more States have ratified human rights treaties, more States have incorporated human rights in their domestic law, and more courts have started to enforce human rights. At the grass roots law level, more organizations have demanded human rights as an entitlement and not just as an aspiration,” explains Ian Seiderman, Legal and Policy Director of the ICJ.

Despite, this long term trend in advancement of human rights, there are warning signs that progress is slowing and in some places has even reversed particularly in the past decade.

“We are now seeing a very strong pushback against human rights proclaimed in the UDHR from countries around the world,” says Ian Seiderman.

“Some of the pressures have come from the security angle, where even States that previously championed rights insist that rights protection must cede to security interest. More recently there has been a rise in populist authoritarian governments that don’t even pay lip service to human rights anymore. And many States have also turned their backs on the commitment to protect the most marginalized and vulnerable, such as refugees and migrants,” he adds.

Roberta Clarke, Chair of the ICJ Executive Committee:

At the normative level, there remains the notable gap in the international legal protection from transnational corporations and other business that abuse human rights and the reticence of many States to participate in good faith in the efforts at the UN to close this gap with a new business and human rights treaty.

This backlash has only redoubled the ICJ’s commitment to fight for the values originally imagined by the writers of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The ICJ and its individual Commissioners remain heavily involved in the development of human rights standards and their implementation based on the UDHR and a part of the larger human rights movement.

The ICJ continues to work to adopt human rights law to changing conditions in the modern world, develops the human rights capacities of lawyers and judges in all parts of the world, undertakes legal advocacy internationally and in many countries, and provides legal tools for human rights practitioners.

Robert Goldman, ICJ President:

On the 70th anniversary of the UDHR, it is critically important to recall why the UDHR was established in the first place, especially in light of the current regression of human rights development around the world.

The preamble of the UDHR reminds us that “ disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind.”

But more critically, it also insists that addressing these and other acts of inhuman rights require that human rights be protected by the rule of law.

This will be the ICJ’s continuing mission.

Dec 2, 2018 | Events, News

On 1-2 December 2018, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) held its 2018 Southeast Asia Regional Judicial Dialogue on enhancing access to justice for women in the region.

Participants included judges from Cambodia, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka and Thailand.

The discussions, held in Bangkok, were focused around resources important for judges to aid in enhancing the capacity of their peers in eliminating gender discriminatory attitudes and behaviours towards women in their work. These resources include a training manual on the use of the Bangkok General Guidance for Judges in Applying a Gender Perspective, and a draft reference manual on women’s human rights and the right to a clean, healthy, safe and sustainable environment.

Frederick Rawski, ICJ’s Director of the Asia and the Pacific Programme, opened the dialogue by emphasizing how important it is for judges to be gender sensitive in their delivery of justice. This could only be done by applying a framework that gives primary attention on ensuring recognition of the applicable human rights, institutional support for the promotion of these rights, and accountability mechanisms for their implementation.

Roberta Clarke, Commissioner of the ICJ and Chair of the organization’s Executive Committee, noted that this judicial dialogue demonstrates the ICJ’s commitment to have a sustainable contribution to the implementation of international human rights standards at the domestic level. She hoped that the judges could contextualize the resources presented and bring these back to their countries for trainings of their peers.

This judicial dialogue is part of a joint project on access to justice for women that ICJ is implementing with UN Women.

Anna Karin Jatfors, UN Women-Asia Pacific’s Interim Regional Director shared that gender stereotypes and social norms which discriminate women are not unique in each country. She pointed out the importance of the ICJ and UN Women collaborating in this project to deconstruct this image to bring better access to justice to women in the region.

Overall, the dialogue was rich and substantive, with the full and active participation from all participating judges who shared their views and experiences on countering gender discrimination in cases before them. At the end of the judicial dialogue, the participating judges expressed strong interest to use the resources for capacity building initiatives of their peers in their own countries.

Contact

Emerlynne Gil, Senior International Legal Adviser, t: +662 619 8477 (ext. 206), email: Emelynne.gil(a)icj.org

Nov 30, 2018 | Events

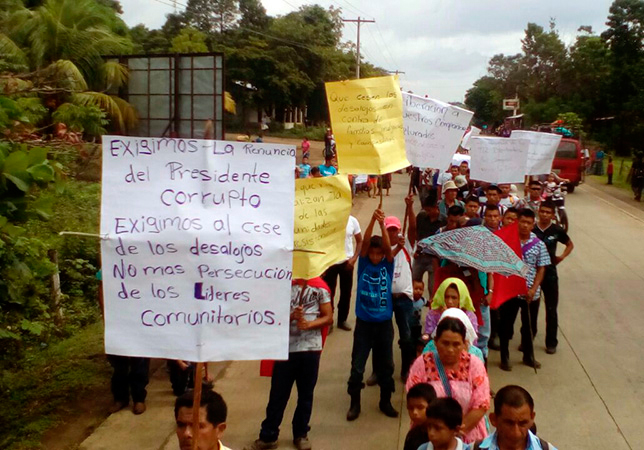

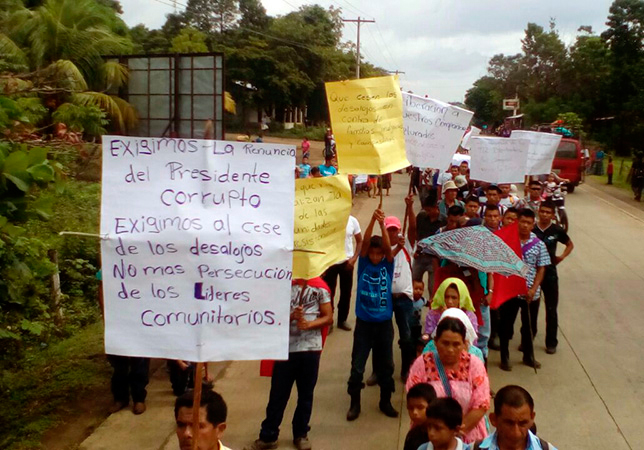

The conference on business and human rights in the Department of Izabal, Guatemala was held at the University of Geneva on 29 November 2018 and co-hosted with the Department of Public International Law and International Organization, Faculty of Law of the University of Geneva and the City of Geneva.

The main issue under review was the impact on the local communities of the operations of the Compañia Guatemalteca de Nickel (CGN-ProNico) a nickel mining company in El Estor, wholly owned by Solway Investment Group, a company registered in Zug, Switzerland.

Speaking at the conference, Prof. Marco Sassòli, a Commissioner of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), recommended there be an international mission to Izabal, Guatemala in order to understand the problems facing the local Q’eqchis communities as a result of the Solway nickel mining operations.

Other speakers included Ramon Cadena, the Director of the ICJ Central America office, Amalia Caal Coc, from the Guillermo Torielo Foundation in Izabal, Guatemala, Maynor Alvarez, the manager of the CGN Community Affairs Department, and Sandra Epal Ratjen, Deputb Executive Director at Franciscans International.

Dr Antonella Angelini from the Department of Public International Law and an expert in business and human rights was the conference moderator.

A more detailed account of the conference proceedings is available (download).

Nov 28, 2018 | News

The Egyptian authorities must drop the charges against nine detainees arrested on 1 November 2018 and immediately and unconditionally release them and at least 31 others arrested and in some cases “disappeared” since late October 2018, or otherwise charge them with a recognizable crime consistent with international law, the ICJ said today.

Those arrested in the present sweeps include human rights defenders (HRDs), lawyers, and political activists and persons otherwise providing support to political detainees. Reports indicate that at least some of those detained are connected to the Muslim Brotherhood. The ICJ is concerned that many if not all of these detainees are being held solely for political reasons.

On Wednesday 21 November, nine detainees held since 1 November 2018—Hoda Abdel Moneim, Mohamed Abu Hurayra, Bahaa Auda, Aisha Al Shater, Ahmed El Hodeiby, Mohamed El Hodeiby, Somaya Nassef, Marwa Madbouly and Ibrahim Atta—were interrogated by the State Security Prosecution, who ordered they be held in pre-trial detention for 15 days.

According to information available to the ICJ, the prosecution charged the nine with joining and funding a terrorist organization and incitement to harm the national economy under Egypt’s Counter-Terrorism Law No. 94/2015 (Case No. 1552/ 2018).

Lawyers representing the detainees were not permitted to access the case files, nor were they allowed to speak with the defendants in private. One of the detainees interrogated on 21 November was also interrogated on 19 November 2018 without the presence of a lawyer. It is unclear when the State Security Prosecution ordered their pre-trial detention.

At least three other detainees also appear to have been interrogated on 24 November 2018, including Ahmed Saad, Ahmed Ma’touk and Sahar Hathout. No information is known about whether an order for their pre-trial detention has been issued.

“These arbitrary arrests and trumped up charges are yet another example of the relentless assault by the military and government on the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression and association and to take part in political activity,” said Said Benarbia, ICJ’s MENA Programme Director. “Targeting anyone having any connection to opposition groups under the government’s ‘war on terrorism’ erodes the rule of law in Egypt, undermines human rights, and means there’s now very little, if any, room to carry out human rights work.”

According to public reports, at least 31 others were arrested by Egyptian authorities in raids in late October or early November 2018. Despite repeated calls on the authorities to provide information regarding their location, their whereabouts remain unknown, raising serious concerns for their health and safety. After human rights lawyer Hoda Abdel Moneim—one of the nine now charged—was held incommunicado for 21 days, her family issued a statement expressing concern about her “dire [physical and psychological] health condition.”

It is well established that the Egyptian authorities engage in the widespread and systematic use of torture. Although Egypt’s Constitution, Criminal Procedure Code and Penal Code require that detainees be held in official places of detention with judicial oversight and prohibit torture and other mistreatment, these safeguards have proven ineffective in practice.

The United Nations Committee Against Torture previously reported on the torture of hundreds of people disappeared by the Egyptian authorities. The ICJ is concerned about the high probability that these detainees have been tortured.

“The authorities should unconditionally and immediately release those arrested solely for exercising their human rights and fundamental freedoms, bring any others immediately before a judge to review whether there is any lawful basis for their detention and for any charges brought, and ensure that all those deprived of their liberty are protected against torture and other ill-treatment,” said Said Benarbia.

Contact:

Said Benarbia, Director of the ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, t: +41-22-979-3817; e: said.benarbia(a)icj.org

Background

Among those arrested in late October and early November 2018 were human rights lawyer and former spokesperson of the ECRF, Mohammed Abu Hureira, and his wife, Aisha al-Shater, daughter of imprisoned deputy chairman of the Muslim Brotherhood, Khairat al-Shater, as well as human rights lawyer Hoda Abdelmoniem, a former member of the National Council for Human Rights, who was arrested at her home after it was raided without warrant. At least eight of the 40 arrested are women. Reports from local human rights lawyers and organizations suggest that the number of persons arrested and arbitrarily detained could be higher.

The arrests are part of Egypt’s orchestrated crackdown on human rights work, in which human rights defenders and critics are arbitrarily arrested and detained, subjected to enforced disappearance, prosecuted in unfair trials, and sometimes sentenced to death. Two other members of the ECRF, including its Executive Director, were arrested in March 2018 and forcibly disappeared in September after an Egyptian Court ordered their release. Following the latest arrests, the ECRF—which documents enforced disappearances and Egypt’s increasing application of the death penalty—suspended its operations in protest.

On 10 September 2018, the Cairo Criminal Court convicted 739 defendants for their participation in the Raba’a Al Adaweyya square protests in August 2013 after a grossly unfair trial, sentencing 75 defendants to death and 658 defendants to life or five to 15 years’ imprisonment.

On 24 April 2018, following an unfair trial, the Cairo military court convicted former judge and former head of the Central Auditing Authority, Hisham Geneina, to five years in prison for “publishing false information harmful to the national security.”

The arrests place Egypt in breach of its international legal obligations, including under the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Article 9 of the ICCPR protects freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention and imposes an obligation on States to ensure a number of protections in respect of detention.

These include the requirement that detainees be brought promptly before a judge so their detention can be reviewed; have the right independently to challenge the lawfulness of their detention; and have the right to access legal counsel. Article 14 of the ICCPR also requires states to ensure detainees have access to legal counsel. Judicial oversight of detention is particularly necessary to protect detainees from torture and cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment.

Articles 19, 22 and 25 of the ICCPR also protect the rights to freedom of expression, to freedom of association and to participate in public affairs. Articles 5-8 of the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders similarly protects such rights exercised by HRDs and Article 12 requires states to protect HRDs from violence, threats, retaliation, de facto or de jure adverse discrimination, pressure or any other arbitrary action for the lawful exercise of such rights.

Under Egyptian Law, Article 56 of the Constitution and Articles 41-42 of the Criminal Procedure Code require that detainees be held in official places of detention and subject to judicial supervision, including judicial power to inspect places of detention and review each detainee’s case. Articles 51-52 and 55 of the Constitution, Article 40 of the Criminal Procedure Code and Article 126 of the Penal Code prohibit torture and other mistreatment.

In June 2018, the ICJ expressed its concerns about Egypt’s repeated renewals of the State of Emergency since April 2017, and the use of the state of emergency to suppress the activities of and persecute students, human rights defenders, political activists, union members and those suspected of opposing the government.

Egypt-November Arrests-News-Web Story-2018-ARA (PDF in Arabic)

Nov 26, 2018 | News

The ICJ convened a Forum of international legal experts and Myanmar civil society actors in Yangon from the 24 to 25 November 2018 on Myanmar’s obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

Representing each of Myanmar’s 14 States and Regions, more than 130 civil society members attended the event, which was co-hosted with the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission in collaboration with Dan Church Aid, Norwegian Church Aid, Equality Myanmar and the Local Resource Center.

The ICJ’s Asia Pacific Regional Director, Frederick Rawski, introduced the Forum objectives which were to raise awareness of the rights, obligations and reporting processes associated with Myanmar’s ratification of the ICESCR on 6 October 2017.

As a State Party to the ICESCR, Myanmar is obliged to respect, protect and fulfill a variety of human rights including the rights to: decent work, an adequate standard of living, adequate housing, food, water and sanitation, social security, health, and education.

The Chairperson of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Virginia Brás Gomes, discussed the vital role civil society plays in documenting and providing information about human rights challenges, and advocating for law to be enforced and interpreted in compliance with the State’s international law obligations.

Virginia B. Dandan of the Philippines, a former Chairperson of the Committee, described the rights protected under ICESCR and highlighted the universality of human rights and the indivisibility of economic, social and cultural rights from other human rights including protection from discrimination.

Visiting Myanmar from the ICJ’s Southern Africa Office, legal adviser Timothy Fish Hodgson, ICJ Legal Adviser in the ICJ Africa Programme, discussed from a comparative perspective the justiciability of ESC rights in South Africa, and the roles lawyers and other civil society actors have played in progressing rights protections.

Legal advisers from the ICJ’s Myanmar Team moderated a series of panel discussions where civil society representatives discussed challenges and opportunities related to the realization of ESC rights in Myanmar.

Separate to this initiative, the visiting international experts also travelled to Nay Pyi Taw to engage with government. Myanmar’s first State report to the ESCR Committee is due in late 2019, also opening opportunities for civil society engagement.

This event was part of the ICJ’s ongoing effort to convene civil society actors to discuss the promotion and protection of human rights through legal mechanisms.