Apr 9, 2021 | Editorial, Noticias

Una opinión editorial de Carlos Lusverti, Consultor de la CIJ para América Latina

El acceso al agua potable y saneamiento es un derecho humano, sin embargo, millones de personas en Venezuela no tienen este derecho protegido o garantizado.

Una de las más importantes medidas preventivas que la Organización Mundial de la Salud ha recomendado para evitar la trasmisión del virus SARS-CoV2 es el frecuente lavado y desinfección de manos. A pesar de esto, en Venezuela millones de personas no pueden hacerlo.

En 2018, al menos el 82% de la población no recibía servicio continuo de agua y el 75% de los centros de salud públicos informó tener problemas con el suministro de agua. La Comisión Internacional de Juristas (CIJ) ha señalado problemas similares sobre el impacto de la pandemia del COVID-19 en otros lugares del mundo, por ejemplo en India y Sudáfrica, aunque la escasez de agua sigue siendo especialmente aguda en Venezuela.

En 2020, el Observatorio Venezolano de Servicios Públicos informó que el 63.8% de la población consideraba que el servicio de agua era inadecuado para enfrentar la pandemia de COVID-19 y solo el 13.6% de la población en ciudades tenía suministro regular de agua.

La Oficina de la ONU para la Coordinación de Asuntos Humanitarios (OCHA) recientemente informó que varias regiones en Venezuela tenían un acceso limitado al agua, señalando que “existía una necesidad urgente de asegurar una necesidad crítica de garantizar servicios adecuados de agua, saneamiento e higiene en salud, nutrición, instalaciones de educación y protección” (Traducción propia).

Incluso antes del inicio de la pandemia por COVID-19, el país ya estaba enfrentando una “emergencia humanitaria compleja” (una crisis humanitaria donde existe un considerable colapso de la autoridad que en Venezuela no es resultado de un desastre ambiental ni un conflicto armado), donde la falta de acceso al agua afecta al menos 4.3 millones de personas.

Impactos de la falta de agua en un sistema de salud en crisis

El agua es indispensable para el consumo doméstico, para cocinar y limpiar; también es necesaria para la protección efectiva del derecho a la salud, que ocupa un lugar central para frenar la pandemia de COVID-19. Los hospitales y otros establecimientos de salud en Venezuela tienen un acceso limitado al agua y sufren cortes del servicio eléctrico, lo cual afecta a la mayoría de los servicios de salud incluyendo las pruebas sobre COVID-19 y su tratamiento.

De acuerdo con el índice Global de Seguridad Sanitaria que evalúa las capacidades de seguridad sanitaria mundial, Venezuela ocupó el puesto 176 entre 195 países en 2019. Esto evidencia el inmenso problema que tenía el sistema de salud para abordar la devastadora emergencia de salud causada por la pandemia de COVID-19; este problema solo se exacerba por el limitado acceso limitado al agua en los establecimientos de salud.

La escasez de agua en establecimientos de salud contribuye a crear un ambiente insalubre y antihigiénico. Los centros de salud, al igual que los hogares, no pueden ser adecuadamente higienizados debido a la falta de agua y a la carencia de artículos de limpieza.

Esto incrementa drásticamente los riesgos para los trabajadores de la salud, los pacientes y, en consecuencia, para sus familias, así como para la comunidad y el público en general. Algunos servicios de salud críticos, como las instalaciones de diálisis y la cirugía en hospitales públicos, han sido cerrados o restringidos debido a condiciones insalubres, lo que ha venido limitando el acceso a los servicios de salud y ha amenazado el derecho a la salud de las personas en el país.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) ha descrito cómo las restricciones en el acceso al agua en los hospitales se han convertido en un problema creciente desde 2014. Estas restricciones pueden variar desde “fin[es] de semana y, en otras ocasiones, directamente no llega por cinco días”. HRW también encontró que “[l]a negativa a publicar datos epidemiológicos por parte de las autoridades debilita significativamente su capacidad de respuesta ante la pandemia.”

Bajo estas condiciones, los trabajadores sanitarios no pueden atender de forma segura a los pacientes de COVID-19 o disfrutar de su derecho a condiciones seguras e higiénicas de trabajo. De acuerdo con la organización Programa Venezolano de Educación Acción en Derechos Humanos (PROVEA), al menos 332 trabajadores de la salud en Venezuela han fallecido desde el comienzo de la pandemia de COVID-19 debido a la falta de equipos de protección personal y otras medidas sanitarias.

Protestas Públicas

Las compañías estatales encargadas del servicio de agua no publican ninguna clase de informes relacionados con la calidad del agua, a pesar de que las ONG locales les han requerido esa información. A través de los años se han realizado varios proyectos para mejorar la calidad del acceso al agua, algunos con financiamiento de entes internacionales como el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, pero las autoridades del país no han dispuesto información pública al respecto. Según Transparencia Venezuela ninguno de estos proyectos está actualmente operativo en el país.

La Alta Comisionada para los Derechos Humanos de Naciones Unidas dijo el 11 de marzo de 2021 que “el acceso a los servicios básicos, como la asistencia médica, el agua, el gas, los alimentos y la gasolina, ya escaseando, se ha visto aún más limitado por el efecto de la pandemia. Esto ha generado protestas sociales y ha agravado la situación humanitaria.”

En 2020, según el Observatorio Venezolano de Conflictividad Social, en medio de la pandemia de COVID-19 y las restricciones de encierro obligatorio, al menos 1833 protestas se realizaron en todo el país reclamando por agua potable. Frecuentemente, las autoridades resolvían estas demandas enviando agua en camiones cisterna.

La frágil situación contribuyó y agravó la falta de acceso al agua potable en el país y las condiciones de vulnerabilidad en las que viven las personas las ha obligado a salir a las calles a reclamar sus derechos en medio de la pandemia. Las protestas públicas en tiempos de pandemia crean riesgos de contraer COVID-19.

Además, en la actual situación de derechos humanos de Venezuela también plantea riesgos de detención arbitraria y uso excesivo de fuerza, que se han vuelto prácticas comunes por parte de las autoridades.

Defendiendo del derecho al agua y al saneamiento en Venezuela

Venezuela es parte del Pacto Internacional de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales y de la Convención Internacional sobre los Derechos del Niño. Ambos tratados establecen obligaciones relacionadas con el derecho al agua y al saneamiento. El Comité de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales ha descrito el derecho al agua como “una de las condiciones fundamentales para la supervivencia” y ha aclarado que los Estados deben priorizar el acceso a los recursos hídricos para prevenir “el hambre y las enfermedades“. No cualquier suministro de agua cumple con este estándar: el acceso al agua debe ser “suficiente, salubre, aceptable, accesible y asequible“.

En el contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19, el Comité ha recordado a los Estados que el derecho al agua debe incluir agua, jabón y desinfectante para todos, de forma continua. Por lo tanto, los Estados deben hacer inversiones adecuadas en los sistemas de agua y saneamiento, incluyendo el uso de la cooperación internacional para ese fin, para contrarrestar efectivamente las pandemias mundiales y mitigar el impacto de la pandemia sobre personas que viven en condiciones vulnerables.

La falta de acceso al agua es un problema de larga data en Venezuela. Las autoridades deben combinar la acción de asistencia inmediata con políticas de largo plazo para garantizar el derecho al agua potable y al saneamiento en el país, de acuerdo con estándares internacionales. Esto incluye la existencia de un mecanismo de monitoreo independiente sobre el suministro de agua en el país.

Durante la pandemia de COVID-19, las autoridades venezolanas deben implementar urgentemente políticas de emergencia para suministrar agua potable en todas las áreas con escasez de agua, sin ningún tipo de discriminación. Se debe dar prioridad a la garantía del acceso al agua en los centros de salud y al suministro de jabón, materiales de limpieza y desinfectante para manos.

Finalmente, las autoridades venezolanas deben adoptar políticas transparentes de acceso a la información pública, de manera completa y oportuna, que permitan comprender la situación epidemiológica y los datos sobre la calidad y accesibilidad del agua.

Esta opinión editorial fue originalmente publicada en el Blog de la Fundación para el Debido Proceso “JUSTICIA EN LAS AMÉRICAS”.

Apr 7, 2021 | News

Victims of gross human rights violations must be provided with effective reparations and guarantees of non-recurrence by Tunisia’s Specialized Criminal Chambers (SCC), judges and prosecutors asserted during a workshop held by the ICJ and the Association of Tunisian Magistrates (AMT) on 3 and 4 April.

The workshop highlighted the need for the SCC to adopt restitution, compensation, rehabilitation and satisfaction measures to achieve to the fullest extent possible reparation for material and moral damage suffered by victims of gross human rights violations in Tunisia.

Participants further emphasized that SCC decisions should include recommendations on guarantees of non-recurrence, including on legal and institutional reforms.

The workshop was attended by more than 25 Tunisian judges and prosecutors attached to the 13 Specialized Criminal Chambers. Discussions involved also international experts and ICJ representatives.

“It is important that the SCC, consistent with international standards, adopt a comprehensive notion of victims and persons entitled to reparation,” said Philippe Texier, ICJ Commissioner.

“In this respect, reparative measures should focus not only on direct victims, but also indirect victims, including the immediate family or dependants of the direct victim and persons who have suffered harm in intervening to assist victims,” he added.

Federico Andreu-Guzmán, international expert, noted the non-derogable nature of the right to reparation under international law and that SCC should seek to ensure that all their decisions comply with this right.

“SCC decisions should include wide-reaching recommendations in order to guarantee that the violations will not be repeated,” said Said Benarbia, Director of ICJ’s Middle East and North Africa Programme.

The workshop also offered the opportunity to participants to discuss a set of recommendations targeting the High Judicial Council and its role in supporting the SCC.

The recommendations, which were developed by a group of SCC judges and prosecutors following the ICJ’s roundtable of 13-14 March, aim to find joint approaches to address ongoing procedural obstacles before the SCC and will be subject of future meetings and roundtable discussions organized by the ICJ and the AMT.

Contact

Valentina Cadelo, Legal Adviser, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: valentina.cadelo(a)icj.org

Asser Khattab, Research and Communications’ Officer, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: asser.khattab(a)icj.org

Apr 2, 2021 | News

The Thai authorities’ adoption of a draft law to regulate non-profit groups would strike a severe blow to human rights in Thailand, several international organizations said today. The bill is the latest effort by the Thai government to pass repressive legislation to muzzle civil society groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

The “Draft Act on the Operations of Not-for-Profit Organizations” contains provisions that would have a deeply damaging impact on those joining together to advocate for human rights in the country, in violation of their right to freedom of association and other rights. The Thai government provided a perfunctory and inadequate consultation process for the bill. Because of fundamental problems in the draft law, the authorities should withdraw the draft entirely and ensure that any future law regulating NGOs strictly adheres to international human rights law and standards, the organizations said.

“This draft law poses an existential threat to both established human rights organizations and grassroots community groups alike. If enacted, this law would strike a severe blow to human rights by giving the government the arbitrary power to ban groups and criminalize individuals it doesn’t like,” said Maria Chin Abdullah, member of ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) and a Malaysian Member of Parliament (MP).

“This draft blatantly breaches Thailand’s own constitution and its human rights obligations. A thriving, independent and free civil society is an essential component of a rights-respecting, open society. The authorities should withdraw this deeply flawed draft and go back to the drawing board,” said Brad Adams, Director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia Division.

Arbitrary and vaguely-defined powers

According to the Draft Act (in Section 3), the government would have wide discretion as to which organizations will be exempted from the application of the law.

The Draft Act (in Section 4) also uses an overbroad definition of not-for-profit organizations (NPO), which has left it open to abusive and arbitrary application by the authorities.

The broad terms of the Draft Act would allow unequal treatment of certain disfavoured groups and carry dire consequences for associations critical of the government, with little scope to legally challenge government decisions. Groups as varied as academic institutions, community groups, sports associations, art galleries and ad hoc disaster relief collectives could be deemed to be NPOs and therefore be subject to the law’s mandatory registration requirement and potential criminal prosecution. The vague and overbroad definition of ‘not-for-profit organizations’ amounts to a violation of the “legality” principle, which requires any restriction to freedom of association and other fundamental freedoms be clearly “prescribed by law”.

Registered and unregistered groups alike must be allowed to function freely and be able to enjoy the right to freedom of association on equal terms. In order to enable individuals to exercise their right to freedom of association, States need to provide a simple, accessible, non-burdensome and non-discriminatory notification process for organizations to obtain their registration and must not require the authorities’ prior authorization.

“The draft law’s broad terms could be applied against virtually any group, no matter how small or informal,” said David Diaz-Jogeix, Senior Director of Programmes at ARTICLE 19. “If passed in its current form, the draft law will likely cause entire sectors of Thai civil society to collapse or take their activities underground.”

Excessive punishments

“Those found in breach of this law’s many faulty provisions risk lengthy prison sentences. Targetted NGOs could have their very existence extinguished at the whim of governmental authorities – enabling the silencing of critical and independent voices in Thailand,” said Ian Seiderman, Legal and Policy Director at the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ).

By making the registration of an NPO mandatory (in Section 5) and rendering any unregistered group illegal, the Draft Act would violate the right to freedom of association and severely impede the work of groups that defend and promote human rights.

Notably, under the proposed law (in Section 10), anyone found to belong to an unregistered association that operates within Thailand could be jailed for up to five years, fined up to 100,000 THB (approx. 3,200 USD), or both. This would effectively criminalize people solely for their peaceful exercise of the right to freedom of association.

“Paranoia” of foreign funding

“Around the world, bogus claims regarding foreign funding for NGOs are constantly used by repressive governments to distract from their own human rights record and to stigmatize and fuel paranoia regarding those who speak truth to power – often simply because they are critical of the government,” said Shamini Darshni Kaliemuthu, FORUM-ASIA’s Executive Director. “Now Thailand seems to want to follow suit, adding itself to an unwelcome list of rights-abusing governments trying to control or severely limit NGO funding.”

The Draft Act (in Section 6) places discriminatory restrictions on organizations that receive foreign funding. Authorities have the sole discretion to determine which activities may be carried out using funds from foreign or international sources, leaving ample room for abuse.

Moreover, the Draft Act states as a rationale for enacting the law: “several [NPOs] accepted money [from foreign sources], and used them to fund activities that may affect the relationship between the Kingdom of Thailand and its neighboring countries, or public order within the Kingdom.” This justification stigmatizes organizations that use foreign funding by equating their objectives to those of “foreign agents”. The government has failed to recognize the legitimate work carried out by organizations and their contribution to the rule of law and development of the country, merely because they are funded by foreign sources.

Privacy invaded and censorship on expression

“In addition to the ongoing criminalization of online expression in Thailand, the Draft Act gives sweeping, unchecked and discretionary administrative powers to the authorities to further obstruct the work of human rights organizations,” said Emerlynne Gil, Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for Research.

The Draft Act not only confers the power to the authorities to closely scrutinize organizations, it also contains provisions to subject NPOs’ offices and members to invasive surveillance and searches without judicial oversight. The Draft Act (in Section 6) allows the authorities to enter civil society organizations’ offices and make copies of their electronic communications traffic data without prior notice or a court warrant. This is a serious threat to the right to privacy and to freely express the ideas and opinions of its members.

Without prior notice or a valid warrant, this arbitrary power clearly violates domestic and international standards on due process of law.

“In going down this route, Thailand stands to poison the space for civil society. The passage of this law would severely undercut Thailand’s claims to be a rights-respecting country with a flourishing civil society,” said David Kode, Advocacy and Campaigns Lead at CIVICUS.

Contact

Ian Seiderman, ICJ Legal and Policy Director, ian.seiderman(a)icj.org, +41 229793800

Download

The statement with additional background information and list of organizations in English and Thai.

Submissions

Amnesty International

Article 19

Human Rights Watch

International Commission of Jurists – English and Thai

Apr 2, 2021 | News

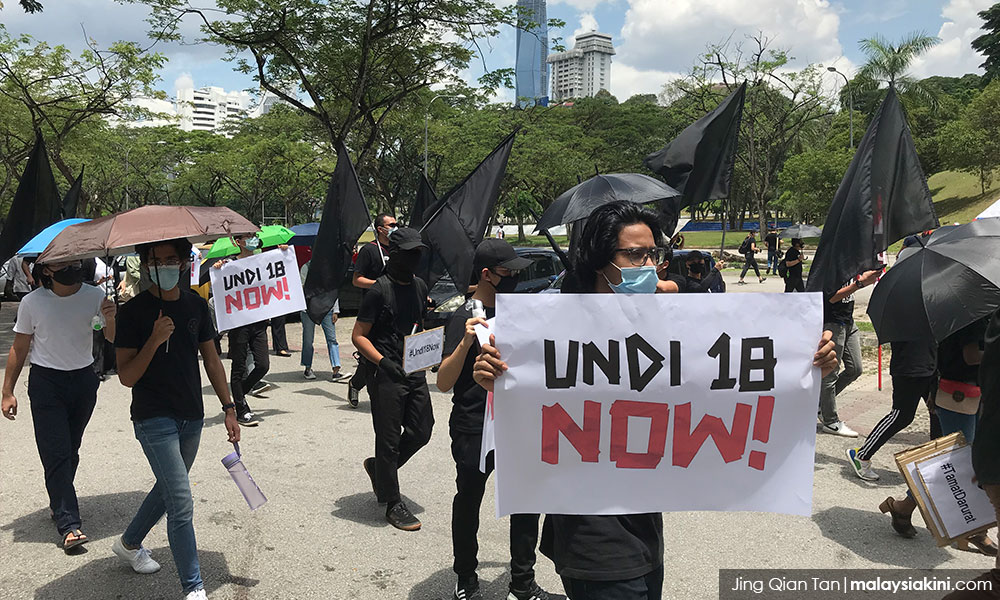

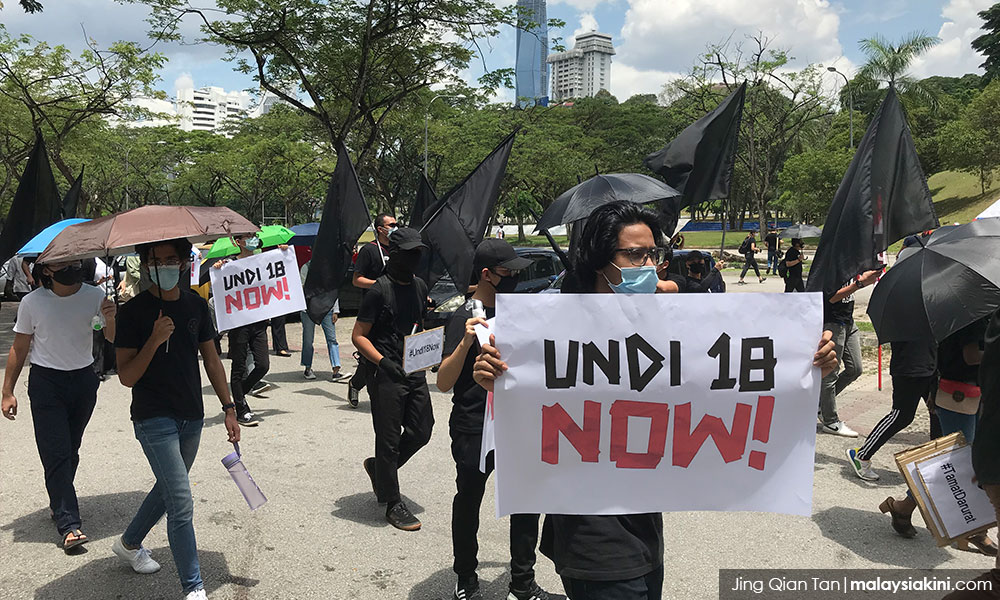

The ICJ today called on the Malaysian authorities to drop their criminal investigations of at least 11 participants in the peaceful Undi18 protests.

The Dang Wangi district police opened investigations against Dato’ Ambiga Sreenevasan, an ICJ Commissioner, and at least ten other individuals including Simpang Renggam MP Maszlee Malik, Petaling Jaya MP Maria Chin Abdullah, and Segambut MP Hannah Yeoh in relation to the wholly peaceful and socially distanced Undi18 protest rally held on 27 March 2021.

They are being investigated for alleged violations of section 9(5) of the Peaceful Assembly Act 2012 (‘PAA’) and Regulation 11 of the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases (Measures Within Infected Local Areas) (Conditional MCO) (No. 4) Regulations 2021 (‘MCO No. 4 Regulations’).

The ICJ said that the application of these laws against the protestors would not be consistent with international law and standards on freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.

The ICJ said that the investigations seem intended to harass and intimidate those who would exercise their rights to free expression and peaceful assembly.

If charged and convicted, violations of the PAA could result in a fine of up to RM$10,000 (approx. USD 2,410). Violations of the MCO No. 4 Regulations may result in a prison term of up to six months and/or a fine of RM$10,000 (approx. USD 2,410).

The ICJ reiterated its previous call for Malaysian legislators to reform the PAA, which imposes unjustifiably burdensome restrictions carrying excessive penalties on the exercise of freedom of expression and assembly.

Contact

Boram Jang, International Legal Adviser, Asia & the Pacific Programme, e: boram.jang(a)icj.org

Background

In July 2019, the Malaysian Parliament unanimously voted to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 years old.

On 25 March 2021, the Election Commission announced that it would postpone the implementation of this new rule from July 2021 to September 2022 at the latest. The Commission cited the COVID-19 lockdowns as a reason for the delay. This would affect the ability of 1.2 million people to vote, if elections are called later this year.

On 27 March 2021, hundreds of individuals gathered peacefully in front of Malaysia’ Parliament building to protest this delay. It was reported that the protestors were wearing face masks and trying to observe physical distancing, with some protestors donning full personal protective equipment.

On 29 March 2021, 11 individuals were summoned for questioning for alleged violations under section 9(5) of the PAA and Regulation 11 of the MCO No. 4 Regulations.

On 30 March 2021, eight of them gave their statements at the Dang Wangi police station in Kuala Lumpur. Four others, including Dato’ Ambiga Sreenevasan, will give their statements on 2 April 2021.

Section 9(5) of the PAA imposes a requirement for a five-day notice of an assembly to the Officer in Charge of the Police District. Failure to do so may result in a fine not exceeding RM$10,000 (approx. USD$2,410). Section 21A also allows the police to issue compounds of up to RM$5,000 instead of a charge being proffered subject to the written consent of the Public Prosecutor.

Regulation 11 of the MCO No. 4 permits the gathering or involvement in a gathering subject to any directions issued by the Director General. Regulation 17 states that failure to comply may result in a fine not exceeding RM$1,000 (approx. USD$241), imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months, or both. Additional emergency laws have raised the potential fine that may be imposed to up to RM$10,000 (approx. USD$2,410).

Apr 1, 2021 | Agendas, Events, News

Migrants and asylum seekers must be provided adequate procedural guarantees in asylum procedures and in immigration detention, a group of experts and judges asserted during a seminar for Greek and Italian judges held by the ICJ, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna (SSSA), and Greek Council for Refugees (GCR) on 29-31 March.

Asylum applicants should have access to adequate information about the procedure and their entitlements in a language they understand, access to a reliable communication system with the authorities, the availability of interpreters, access to legal aid, and reasoned decisions, experts said during the seminar, held in the framework of the FAIR plus project. Speakers further emphasized that immigration detention must be subject to automatic review by an independent body with a power to release detainees, especially when removal is no more an option.

More than 30 judges from Italy and Greece came together for this event to discuss procedural guarantees for migrants and asylum seekers, related to the safe third country concept, the access to legal assistance and interpretation, safeguards related to immigration detention, and procedural guarantees in the asylum procedure, especially in the accelerated procedures.

A summary of the discussions

On the first day, the judges exchanged overviews of national systems and presented some specific questions regarding the Italian and the Greek systems. Following the discussion on the safe third country concept and its implementation in Greece, an Italian judge presented recent developments in the Italian case-law, and the role of the judge, country of origin information, accelerated procedures, the length of procedures and the question of credibility assessment.

On the second day, the discussion related to the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on the rights of migrants and asylum seekers took place. The situation in Greece and in Italy was described by judges, in particular in relation to the access to the asylum procedure, the lawfulness of detention, the right to health and the question of access to a personal hearing when some of the hearings take place electronically.

An overview of the situation of immigration detention in Italy and Greece was presented by an Italian lawyer and an expert from UNHCR Greece. Speakers highlighted that in cases when people cannot be returned, they should not be kept in detention without a legal basis.

Accelerated procedures in law and in practice in both countries have been introduced by UNHCR Greece and Italy were addressed through a case-study and discussion, covering mainly the specific needs in accelerated procedures, automatic suspensive effect of appeals, and time limits in the accelerated procedures.

Finally on the last day, two lectures were delivered by Ledi Bianku, a former judge of the European Court for Human Rights, and an Associate Professor at the University of Strasbourg. First, looking into the guarantees in asylum and migration proceedings, Ledi Bianku stressed the need to always provide asylum applicants adequate information about the procedure and their entitlements in a language they understand, access to a reliable communication system with the authorities, the availability of interpreters, access to legal aid, and reasoned decisions in order to provide access to an effective remedy. In the second part of his intervention, Mr. Bianku discussed the detention of migrants, where he stressed the need for automatic review of detention, especially when removal is no more an option, by an independent body with a power to release.

The FAIR plus project is a judicial training and cooperation project supported by the European Union’s Justice programme, focusing on four countries Ireland, Greece, Italy and the Czech Republic. The aim of the project is to contribute to better judicial protection of the fundamental rights of migrants across the EU. Within the project the ICJ and partners are drafting of training materials and relevant legal briefings, implement training of the existing judicial trainers in the target countries, conduct four national trainings, two transnational seminars, and an international roundtable. The project is implemented in collaboration with national partners: Immigrant Council of Ireland (ICI), Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna (SSSA), Greek Council for Refugees (GCR) and Forum for Human Rights (Czech Republic).

Please find the agenda here.