Sep 23, 2015

An opinion piece by Daniel Aguirre, ICJ International Legal Adviser based in Yangon, Myanmar.

A newly drafted investment law – much awaited by investors eager to access Myanmar’s market – has been completed and will be submitted to the Hluttaw (photo) at its next session.

The much-improved draft goes a long way toward protecting the rights of people and the environment in Myanmar from foreign investments that may create and aggravate human rights and environmental problems.

The most significant improvements to this draft of the national investment law are that it does not give foreign investors recourse to international investor-State dispute mechanisms (ISDMs) and includes key provisions protecting the government’s ‘right to regulate’ in favour of human rights and the environment.

Civil society organizations, including the ICJ, have advocated for these changes to prevent foreign investors from using international arbitration as a means to challenge public policy designed to protect human rights and the environment.

This draft law stands in sharp contrast with the bilateral investment treaties (BITs) that Myanmar has signed with a number of major foreign investors (for example, China, India, Japan, Philippines and Thailand), all of which include troubling provisions that can undermine the government’s ‘right to regulate’ in favour of the environment and human rights.

That is why Myanmar’s lawmakers in the Hluttaw must now ensure that they adopt the latest draft of the investment law without diminishing it.

They should recognize civil society’s calls for the promotion of responsible investment as well as the protection of the environment and human rights.

Investment Law is a major factor in Myanmar’s efforts to ensure sustainable development.

It is also a means by which to ensure that Myanmar will be able to discharge its human rights obligations.

The national investment law, if adopted in present form, is also very important because it should serve as the basis for future BIT negotiations, for instance with the European Union and the United States.

It is a credit to the Directorate of Investment and Companies Administration (DICA) that it stood up to pressure from both international and domestic investors greedily eyeing Myanmar’s abundant resources.

Instead, DICA undertook a consultative process in which civil society was able to voice their concerns about the previous draft of the investment law.

There were a number of consultations and the process was by no means perfect.

But the adoption of a consultation process is an important step in Myanmar – one unheard of a few years ago – and has resulted in a better law put forward. Unfortunately, the same process has not been adopted during the negotiation of Myanmar’s BITs.

Economic investment should contribute to the rule of law and human rights.

But in order for this to happen, Myanmar must align policies with a vision of development based on local and national aspirations, placing people, and their rights, at the centre of the process.

As such, investment law, both in the national and international contexts, must be part of an overall development strategy.

It should refer to the various legal regimes, such as international human rights law, environmental conservation and BITs, with which it will interact. DICA has done its part to produce a draft in consultation with the public.

The decisions to be made now in the Hluttaw will shape Myanmar’s economic development and influence the protection of human rights and the environment for decades to come.

The much-criticized previous draft gave priority to investment protection over human rights.

Individual foreign investors could use arbitral panels to defeat government regulations if they hurt their profits – possibly even if such regulations were in line with Myanmar’s constitutional obligation to protect human rights.

The new draft of the national law, by contrast, refers to responsible investment and the protection of the environment.

It also sets out general exceptions to the protections for investors, allowing the government to regulate in favour of the environment and health.

It clarifies that Myanmar’s international legal commitments will be considered in arbitration.

This signals the government’s intention to regulate in these areas in the future. This intention should also be reflected in Myanmar’s BITs and the country should renegotiate old treaties that do not protect its ‘right to regulate’.

Myanmar has recently signed, though not yet ratified, the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, signaling its willingness to put in place policies to progressively achieve healthcare, education and social security.

These rights are also protected in Myanmar’s constitution. It is these types of rights that require the public policy regulation threatened by BITs.

Civil society’s concerns over the lack of human rights or environmental safeguards in investment law are not idle fears: investment protection can generate costly disputes – some arbitral awards run into the billions of dollars.

In effect, investors’ interests become legally protected, while the people of Myanmar must rely on the underdeveloped national legal system that does not provide adequate access to justice.

There are a growing number of international examples where new laws and regulations passed by democratically elected governments to protect economic, social and cultural rights have been challenged by foreign investors through BITs because they would decrease their profits.

For example, Phillip Morris Asia, a tobacco company, is using an ISDM to legally challenge the Australian government over its plain packaging regulations, which were designed to curb cigarette consumption.

Investment law should provide certainty to investors and protect their interests from random or discriminatory change to government regulations or policies.

But in Myanmar a wide range of laws and policies is missing or in nascent stages of development.

Improperly prioritizing protection for investors would dissuade Myanmar from adopting policies, such as strict environmental protection, public health or human rights standards.

Myanmar must ensure that it retains a right to regulate in both its national investment law and its international agreements.

These powers must be used for legitimate public policy rather than discriminatory protectionism.

Photo credit: Htoo Tay Zar

Aug 4, 2015

An opinion piece by Kingsley Abbott, ICJ International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia

The trial of two Thailand-based journalists from the online news outlet, Phuketwan, accused of criminally defaming the Royal Thai Navy, appeared to be a very sabai sabai affair as I monitored the trial for the ICJ between 14 and 16 July in Phuket, Thailand.

But beneath its calm surface, the proceedings were part of an insidious and exceptional legal battle, as a government institution – the Royal Thai Navy – sought criminal punishment for the defamation of its reputation.

The presiding judge was not antagonistic toward the defence, and I observed no obvious procedural irregularities during the trial.

Initially, eight defence lawyers faced off against a sole prosecutor. However, on the morning of the second day the prosecutor notified the Judge that she had no questions for the defence witnesses and disappeared for the remainder of the trial.

On 17 July 2013, Phuketwan published an article that contained a paragraph reproduced from a Pulitzer award winning Reuters article that alleged that ”Thai naval forces” were complicit in the smuggling of Rohingya, a persecuted ethnic minority from Myanmar.

In December 2013, the Royal Thai Navy reacted by filing a complaint against Big Island Media, the parent company of Phuketwan, and the two Phuket-based journalists, Chutima Sidasathian and Alan Morison (photo), alleging criminal defamation under the Thai Criminal Code and violation of Article 14 of the Computer Crimes Act.

The maximum penalties for these crimes are two years and five years imprisonment, respectively.

No charges have been laid against Reuters.

Numerous governments, UN agencies and human rights groups, including the ICJ, have called for the charges to be dropped.

Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Thailand is a State Party, guarantees the right to freedom of expression, which includes the right to impart information.

Defamation laws should never be used to criminalize free expression, particularly when the expression involves criticism of public authorities, made without malice and in the public interest, as was undoubtedly the case here.

To guard against such violations of freedom of expression, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, the Human Rights Committee, the ICJ and other international experts have urged states to abolish criminal defamation entirely.

This case comes against the background of international furor surrounding the discovery of mass graves allegedly linked to traffickers on both sides of the Thailand-Malaysia border and the horrific plight of thousands of Rohingya and Bangladeshis who were found adrift in the Andaman Sea.

Still, the Thai government has pursued the case, which was one of the facts noted by the US State Department when it gave Thailand the lowest rating for the second year running, Tier Three, in its influential 2015 Trafficking in Persons Report.

There has been speculation that the low-key (and eventually, nonexistent) prosecutorial presence suggests the Government is not pushing the case hard, but according to experienced Thai lawyers, the prosecution sometimes leaves a trial when it is confident of its case.

The four witnesses for the prosecution mostly testified about the administrative aspects of the case: the first was the Navy officer who made the complaint, while the other three were the police officers who received and acted upon it.

The investigation appeared to have been rather superficial. For example, the police did not interview anyone other than the two Phuketwan journalists, and had not checked the Thai translation of the article relied on by the Navy which erroneously translated “Thai naval forces” into “Royal Thai Navy,” this being a key part of the defence case.

While waiting for the arrival of the final prosecution witness, the Judge asked one of the journalists, Chutima Sidasathian, why the case had not settled at a mediation facilitated by the National Human Rights Commission.

She answered that despite their best efforts to reach a settlement, she and her co-accused were not prepared to apologize for exercising their journalistic duty to report on matters in the public interest, especially when the facts were reproduced from the story of another news agency.

During the trial, both sides said there was no animosity between the Royal Thai Navy and Phuketwan, which has regularly reported favorably on the Royal Thai Navy’s activities.

Earlier this year, Chutima Sidasathian, who is studying for a Ph.D on the Rohingya, had been asked by the Prime Minister’s office to advise it on the Rohingya crisis.

The defence presented their case through seven witnesses, including the two journalists.

Their evidence sought to establish that the journalists were merely exercising their duty to report on matters in the public interest, that they had never intended to defame the Royal Thai Navy but had simply reproduced a passage from a Reuters article that referred to “Thai naval forces” not the Royal Thai Navy who were therefore not a damaged party, and that the Computer Crimes Act was never intended to apply to cases of this kind.

As the prosecutor was absent during the entire defence case, this evidence was not challenged.

The accused, their Thai media colleagues, and the international community now await the verdict, which will be delivered on 1 September 2015.

Regardless of the outcome and based on the proceedings so far, it is clear that under international law, the Royal Thai Navy and the prosecution must immediately withdraw the charges, and that Thailand’s criminal defamation laws should be scrapped to ensure compliance with its international obligations.

Journalists in Thailand must never again face such ill-founded proceedings, or hesitate to report on matters in the public interest for fear of being unjustly dragged through the courts by the authorities.

Thailand-Phuketwan-News-OpEd-2015-THA (PDF with full text of the opinion piece in Thai)

Aug 2, 2015

An opinion piece by Nikhil Narayan, ICJ Senior legal Adviser in Nepal and Sanitha Ambast, ICJ International Legal Adviser in India.

When former Nepal Prime Minister and UCPN (Maoist) Chairman, Pushpa Kamal Dahal visited Delhi in mid-July 2015, India’s President, Prime Minister, and members of major political parties voiced their support for the early finalization and adoption of Nepal’s constitution.

Prime Minister Modi asked Nepal to ensure that the constitution was drafted with the support of as many stakeholders as possible.

However, this advice seems to have been ignored given the manner in which the constitution-making process has been fast-tracked in Nepal.

The process underway is seriously flawed, and has resulted in a draft that ignores important human rights obligations.

While continuing to support timely progress, India should encourage the authorities in Nepal to develop a legitimate and rights-respecting Constitution through an inclusive and participatory process.

Nepal’s constitutional drafters began their work over seven years ago, but the process stalled repeatedly due to political disagreements.

However, the earthquake of 25 April 2015, combined with emerging consensus among the major political party elites, has meant that recent weeks have seen sudden and remarkable progress towards the finalization of a Constitution.

Nepal’s four major political parties reached an internal agreement on 9 June 2015, in which they avoided dealing with the contentious federalism issue by agreeing to leave the discussion on the territorial boundaries and names of the new federal entities to a federal commission to be established later.

The Constitution Drafting Committee was then asked to prepare a preliminary text of the Draft Constitution. Nepal’s Constituent Assembly (CA) endorsed this Draft Constitution on 7 July 2015, paving the way for ‘public consultation’ on the provisions of the Draft.

The Committee on Public Relations and Opinion Collection was given 15 days starting 9 July 2015 to consult with and solicit views from the Nepali public throughout the country on the Draft Constitution, consolidate them, and produce a report for the CA. This period ended at the end of last week.

A two-week timeframe to read and respond to a constitutional document that is over 100 pages long is grossly inadequate. As reports have indicated, Nepali people in some regions were effectively given only two or three days to provide inputs.

While a few groups and individuals managed to make submissions, in several other districts people protested the contents of the Draft, and the police responded with force. The monsoon rains further hampered public accessibility to meetings.

It is also unclear whether and to what extent people living in remote areas and/or areas rendered inaccessible by the rains, persons affected by the earthquake, illiterate persons, non-Nepali speakers, and persons living with disabilities, including people who are vision-impaired, were consulted.

It is hard to imagine that the Committee on Public Relations and Opinion Collection was able to process in any detail the views and suggestions collected through the consultation and adequately analyze them within the mandated 15 days.

The Draft Constitution is substantively problematic and several rights are not adequately protected.

The citizenship provisions are vague and discriminatory, and risk rendering people stateless by requiring that children born in Nepal may only obtain citizenship if both mother and father are identified and are Nepali citizens themselves. Non-citizens are excluded from key entitlements and protections.

The provisions on gender equality are controversial, with activists arguing that the current formulation does not guarantee the full range of women’s reproductive rights.

Several economic and social rights are defined inadequately, thus not offering the protections required by international human rights law.

Allowance for restrictions on the rights to free speech, expression, information and press freedom, as well as the rights to freedom of association and assembly, are broad and vague and exceed what is permitted under international human rights standards.

Provisions on remedy for human rights violations are lacking. And guarantees for securing judicial independence are weak and inadequate.

An inadequate consultative process means that people do not have the opportunity to point out these flaws, or to advocate for a Constitution that addresses the root causes of the past conflict and enhances respect and protection of all human rights.

This also means that the Constitution, and the state structures it establishes, may lack necessary public legitimacy and ownership from the outset.

Ensuring genuine consultation and public participation in democratic processes – particularly the constitution-making process – is crucial for the legitimacy of the Constitution and the rule of law in democracies, and would be wholly consistent with Nepal’s obligations under international human rights law.

Public participation is particularly important given the constitutional history of Nepal.

Nepal has had six Constitutions since 1948. Each of these Constitutions, whether authoritarian or democratic in nature, was promulgated without a participatory process.

A major accomplishment of the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which marked the end of the civil war in Nepal, was to commit to a Constitution that respected “people’s right to information, transparency and accountability” and “people’s participation”.

While broader consultation may take slightly longer than the “fast tracked” process, it will be a valuable investment if it results in a strong and lasting Constitution.

India has a political and economic stake in a Nepal that is democratic, peaceful and prosperous. A Constitution developed on the basis of a genuine and inclusive participatory process is not just a human right.

It also enhances the likelihood of popular ownership of the Constitution, which was lacking in Nepal’s previous Constitutions, thus improving the chances for peace and stability in the nation.

Photo credit: Sebastian Werner

Jul 21, 2015

An opinion piece by Vani Sathisan, Sanhita Ambast and Reema Omer, ICJ International Legal Advisers for Myanmar and South Asia, respectively.

Blasphemy prosecutions are undermining the rule of law in Myanmar, India and Pakistan.

Blasphemy laws, such as section 295A of the penal code, are inconsistent with human rights including freedom of opinion and expression, freedom of thought, conscience, and religion, the right to liberty, and the right to equality before the law without discrimination.

They are also applied arbitrarily and accused persons are often punished after unfair trials.

Section 295A, enacted by colonial authorities in 1927 to curb communal tension, is the same in all three countries.

It states that, “deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs” shall be punished with imprisonment, or with fine, or with both.

In a litany of recent cases, however, courts have convicted individuals in the absence of evidence of any deliberate and malicious intent to insult a religion.

People have been severely punished simply because their acts of expression without such intent were perceived to be at odds with conservative interpretations of a religion. In Myanmar, at least, statements offensive to minority religions go unpunished.

Earlier this year in Myanmar, Philip Blackwood and his colleagues Tun Thurein and Htut Ko Ko Lwin, were jailed for two and a half years with hard labour under 295A for distributing on Facebook a psychedelic image of the Buddha wearing headphones to promote their bar.

More recently, Htin Linn Oo, a writer and National League for Democracy information officer, was sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labour under 295A.

An edited ten-minute video of his two-hours speech at a literary event was posted on social media, outraging some Buddhist groupsA Buddhist himself, he had questioned the Buddhist credentials of those using Buddhism to incite violence.

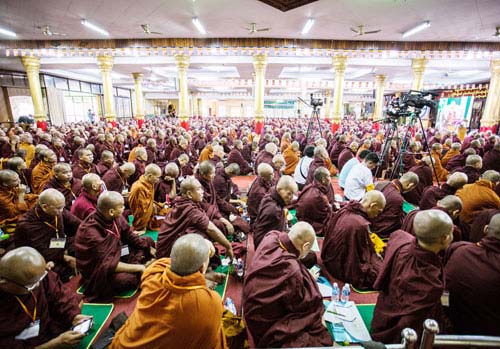

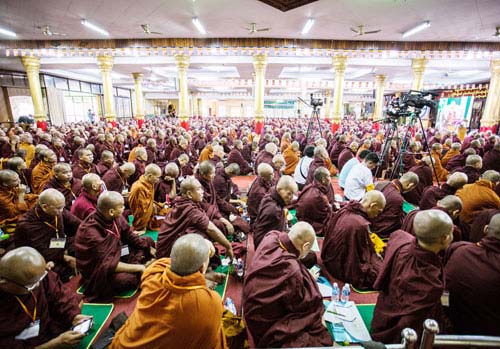

The Ma Ba Tha, an ultra-nationalist movement seeking to “control the spread of Islam” in predominantly-Buddhist Myanmar, and other nationalist monks, protested outside the court and demanded for a tougher punishment.

The District Court rejected his appeal, reportedly stating it “should not interfere” with the lower court’s decision.

These convictions violate international law, including a range of human rights recognized by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and by international treaties.

Myanmar’s Constitution guarantees the right to freedom of expression, conscience, and to freely profess and practice religion, and this, together with the absence of proof of intent, make the convictions difficult to reconcile with Myanmar’s own laws.

The convictions are a worrying indicator of growing religious intolerance in the country.

Examples from India demonstrate how the very existence of section 295A can chill free speech, even before a case has a chance to reach the courts.

Section 295A has been used to arrest and charge individuals who express allegedly “outrageous” opinions, even without evidence of intent.

Shaheen Dhada and Renu Srinivasan, for example, were originally charged under 295A for criticizing Mumbai’s shut down following the death of right-wing politician, Bal Thackeray, on Facebook. This charge was later modified.

In 2014, Penguin India decided to withdraw publication and destroy remaining copies of Wendy Doniger’s scholarly work “The Hindus: An Alternative History” in response to a case filed under section 295A by a right wing religious group accusing the book of hurting Hindu sentiments.

While police may drop such charges at a later stage, section 295A has still damaged free expression by enabling the initial harassment.

Pakistan has enacted even broader provisions such as section 295C of the Pakistan Penal Code, criminalizing words, representations, imputations, innuendos, or insinuations, which directly or indirectly, lead to “defiling the sacred name of the Holy Prophet”.

Courts are even more willing to dispense entirely with proof of intent or any objective standard for what constitutes blasphemy under this section.

The UN Human Rights Committee established by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (a key human rights treaty to which India and Pakistan are parties), has emphasized that, “Prohibitions of displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws, are incompatible with the Covenant”.

The only limited exception under the Covenant would be for proportionate and non-discriminatory measures to prohibit “advocacy of … religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence”; section 295A, and in Pakistan, section 295C, fall far short of this threshold.

The incompatibility of these laws with international human rights, as well as their discriminatory application, renders the proceedings and punishments based upon them arbitrary.

The concern is all the more acute when the judicial systems lacks independence or impartiality, as the ICJ has found to be the case in Myanmar, or where blasphemy trials are grossly unfair and the prescribed punishment is mandatory death penalty, as in Pakistan.

Those who support prosecutions under the blasphemy laws may honestly believe they are protecting the dignity of their religion, but by violating human rights such prosecutions deny the human dignity of the defendants and undermine the rule of law for all.

The laws must be repealed or fundamentally changed, ongoing prosecutions ended, and those imprisoned for their beliefs or protected speech immediately and unconditionally released.

Photo: Zarni Phyo/The Myanmar Times

Jul 16, 2015

An opinion piece by Vani Sathisan, ICJ International Legal Adviser in Myanmar and James Tager, a Harvard Satter Fellow with the ICJ.

Over the past three months, the ICJ has written to investors, developers, an international audit company and an environmental research institute to ask for the public disclosure of information relating to two of Myanmar’s largest economic development projects: The Dawei and Kyauk Phyu Special Economic Zones (SEZs).

The ICJ asked for information regarding environmental impact assessments, environmental management plans, and financial audit reports.

The ICJ received no substantive responses.

The Dawei (photo) and Kyauk Phyu SEZs, two of Myanmar’s three proposed SEZs, are key elements of the country’s economic development plans.

Transparency about the proposed projects is vital to ensure the protection of those whose rights will be affected by these massive investment projects. The Myanmar government, and interested investors, must remove the secrecy around these projects and provide the basic information requested regarding these projects.

In a country where businesses normally proceed without input from local communities, such secrecy has fostered serious human rights abuses, including land misappropriations, loss of livelihoods, serious environmental damage, and violent curtailments of freedom of expression and association.

The two SEZ projects will include a power plant, industrial zones, a natural gas terminal, a water reservoir, and substantial infrastructure, which can have massive effects on the environment and the health of nearby communities. The experience in Rakhine State, where the proposed Kyauk Phyu SEZ will be located, is instructive: development of gas fields and other resource extraction projects have been fraught with allegations of forced labour and the forced eviction of hundreds of farmers from their lands.

The companies operating in SEZs are not the only ones rejecting transparency.

When the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre recently wrote to over a hundred foreign companies operating in Myanmar, seeking details on their activities and human rights commitments, only a quarter responded with relevant information, another quarter provided general statements, and approximately half failed to respond altogether.

Lack of transparency around projects with potentially harmful environmental and social impacts can leave communities vulnerable to abuse. They can also affect investors, exposing them to project delays, litigation, and reputational damage.

Myanmar is increasingly seeing examples where lack of transparency at the early stages of a project hurt companies—and more important, the communities among which they work.

The Letpadaung copper mining project, a joint venture between Chinese-owned Myanmar Wanbao and the military-owned Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited, has displaced hundreds of families amidst an opaque land acquisition process and a lack of genuine consultations with the affected communities.

Protests about the mine were quelled with police firing white phosphorous to break up a protest in 2012 and the shooting death of a protestor in 2014.

Wanbao finally published its environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) report just last week, but only after Letpadaung had attracted unwanted attention as an example of human rights abuses and corporate malfeasance.

Even where laws for corporate transparency exist, for instance the human rights reporting requirements imposed by the United States government, some US companies avoid disclosing their investments and activities in Myanmar, at times by incorporating in other jurisdiction such as Singapore.

Notwithstanding such evasive tactics, the responsibility ultimately rests with the Myanmar government to hold investors to account by enforcing regulations, including demands for corporate transparency and the country’s environmental regulations – such as they are.

Myanmar’s Environmental Conservation Law currently mandates an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for all investment projects, but the law still lacks clear and enforceable environmental controls. The EIA Procedures, which would set out the specific requirements for EIAs under the Law, remain in draft form.

The most recent draft that the ICJ has seen includes the requirement that project proponents share the EIAs with civil society and local communities. It is vital that these disclosure provisions remain in the final EIA Procedures.

Corporate officers and government officials will continue to refuse to disclose EIA results if they do not believe that working with affected communities is an obligation.

But Myanmar’s government has the obligation, under international law, to uphold the rights of its people to informed participation in environmental decision-making.

These obligations must start with government officers committing to sharing information with communities affected by proposed projects, and must continue with enforcement of regulations ensuring that corporate actors do the same.

When it comes to questions about the environmental effects of projects that will affect Myanmar’s communities, silence cannot be the answer.