India: Arbitrarily detained Kashmiri prisoners must be freed

ICJ has joined other NGOs in welcoming steps taken by Indian authorities to decongest prisons in an effort to contain the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). The Government should release all unjustly detained prisoners as a matter of priority.

The joint statement read as follows:

The fate of hundreds of arbitrarily detained Kashmiri prisoners hangs in the balance as the number of confirmed cases of coronavirus in India passes the 4,000 mark and many more are likely to remain undetected or unreported.

Inmates and prison staff, who live in confined spaces and in close proximity with others, remain extremely vulnerable to COVID-19. While the rest of the country is instructed to respect social isolation and hygiene rules, basic measures like hand washing – let alone physical distancing – are just not possible for prisoners.

Under international law, India has an obligation to ensure the physical and mental health and well-being of inmates. However, with an occupancy rate of over 117%, precarious hygienic conditions and inadequate health services, the overcrowded Indian prisons constitute the perfect environment for the spread of coronavirus.

In a bid to contain the spread of the disease among inmates and prison staff, the Supreme Court asked state governments on 23 March 2020 to take steps to decongest the country’s prison system by considering granting parole to those convicted or charged with offenses carrying jail terms of up to seven years.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet also called on governments to “examine ways to release those particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, among them older detainees and those who are sick, as well as low-risk offenders.”

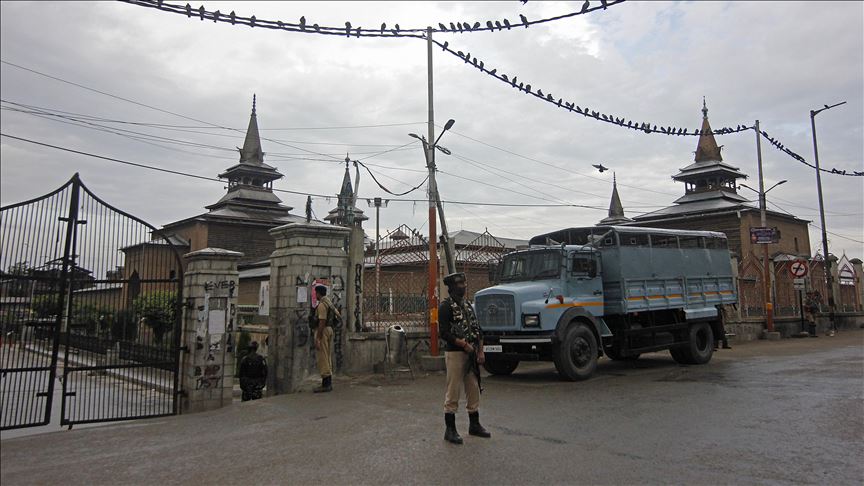

Various state governments in India have now begun releasing detainees. However, there is a concern that hundreds of Kashmiri youth, journalists, political leaders, human right defenders and others arbitrarily arrested in the course of 2019, including following the repeal of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution on 5 August 2019, will not be among those benefiting from the measure. Article 370 provided special status to Jammu & Kashmir.

Human rights groups and UN experts have repeatedly called for the release as a matter of priority of “those detained without sufficient legal basis, including political prisoners and others detained simply for expressing critical or dissenting views.”

Last month, the Ministry of Home Affairs revealed that 7,357 persons had been arrested in Jammu & Kashmir since 5 August 2019. While the majority have since been released, hundreds are still detained under sections 107 and 151 of the Criminal Procedure Code, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), and the Public Security Act (PSA), a controversial law which allows the administrative detention of any individual for up to two years without charge or trial. Reportedly, many of those still detained are minors.

Many of those detained were transferred to prisons all across India, thousands of kilometers away from their homes, hampering their lawyers’ and relatives’ ability to visit them. Some of the families, often too poor to afford to travel, have been left with nothing but concerns over the physical and psychological well-being of their loved ones.

Mr. Miyan Abdul Qayoom, a human rights lawyer and President of the Jammu & Kashmir High Court Bar Association, was also cut off from his family and lawyer. Detained since 4 August 2019 in India’s Uttar Pradesh State, he was transferred to Tihar jail in New Delhi following a deterioration of his health. Mr. Qayoom, 70, suffers from diabetes, double vessel heart disease, and kidney problems.

Mr. Ghulam Mohammed Bhat was also transferred to a jail in Uttar Pradesh. In December 2019, he died thousands of kilometers away from his home at the age of 65 due to lack of medical care.

With the entire country in a lockdown and a ban on prison visits for the duration of the outbreak imposed, inmates are more isolated from the outside world than ever. In such a situation, prison authorities must ensure that alternative means of communication, such as videoconferencing, phone calls and emails, are allowed. However, this has not often been the case. Especially in Jammu & Kashmir, where full internet services are yet to be restored after a communication blackout imposed on the population on 5 August 2019, contacts between inmates and the outside world are even more limited.

- Amnesty International India

- Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

- CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

- International Commissions of Jurists (ICJ)

- International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

- World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

To download the statement with detailed information and key recommendations, click here.