Apr 1, 2021 | News

The conviction of political activists Martin Lee, Margaret Ng, Jimmy Lai, Lee Cheuk-yan, Albert Ho, Leung Kwok-hung, Cyd Ho for their role in organizing public protests in 2019 delivers a massive blow to human rights and the rule of law in Hong Kong, said the ICJ.

“These convictions are the latest attack on the already weakened standing of the rule of law and democracy in Hong Kong,” said Ian Seiderman, the ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director.

The defendants were convicted by West Kowloon Magistrates’ Court on joint charges of organizing an unauthorized assembly under section 17A(3)(b)(i) of the Public Order Ordinance Cap. 245 and knowingly taking part in an unauthorized assembly under section 17A(3)(a) of the same Ordinance. Two other defendants, Au Nok-hin and Leung Yiu-chung, pleaded guilty in February before the trial began. They face up to five years in prison. Their sentences will be handed down at a later date.

“These prosecutions and convictions constitute persecution of human rights defenders, journalist, and politicians through abusive legal process. The unauthorized assembly provisions of the Public Order Ordinance has been used to silence lawful expressions of on matters of public concern,” said Ian Seiderman.

The Hong Kong SAR, though not the rest of the People’s Republic of China, is legally bound by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which guarantees to the right to freedom of assembly and expression. The ICCPR continues to be in force in Hong Kong by virtue of Article 39 of the Basic Law. The United Nations Human Rights Committee has repeatedly expressed concern that charging people under the Public Order Ordinance against peaceful protesters in Hong Kong stands to violate their human rights under the ICCPR.

The ICJ has previously pointed out that imposing criminal charge on people exercising their right of peaceful assembly who fail to comply with a procedural requirement, such as notification, unduly restricts freedom of peaceful assembly by adding unnecessary barriers to public gatherings. Furthermore, the sentencing guidelines of the Ordinance, which include the possibility of a peaceful participant of a public assembly being sentenced to five years in prison if the organizers fail to comply with the notification requirement, are extreme, disproportionate and open to abuse.

Background

On 12 August 2019 the Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF) submitted a Notification of Intention to hold a public meeting and procession, informing the police of the intention to hold a public assembly on 18 August 2019 starting from Victoria Park and ending at Chater Road, and a second public assembly at Chater Road. The police objected to the public procession from the Park to Chater Road. The CHRF appealed against the police decision and after an appeal hearing convened by the Appeal Board on 16 August 2019, the Board upheld the police decision and dismissed the appeal lodged by CHRF.

The CHRF held a press conference on 17 August 2019 wherein they said the police had not arranged for the dispersal of crowds from Victoria Park so pro-democracy legislators and other influential activists would be assisting the crowds to disperse safely to nearby MTR stations. On 18 August 2019 during the public assembly at Victoria Park and the defendants carried a long banner out of Victoria Park Gate 17 and led a procession of people to Chater Road, Central. The route taken followed the previously proposed route of the banned public procession. The procession finished at Chater Road with the defendants laying the long banner down on the road.

Contact

Boram Jang, International Legal Adviser, Asia & the Pacific Programme, e: boram.jang(a)icj.org

See also

Mar 31, 2021 | News

Today, the ICJ submitted recommendations to Thailand’s Office of the Council of State concerning the Draft Act on the Operation of Not-for-Profit Organizations B.E. … (‘Draft Act’), which is scheduled for public consultation between 12 and 31 March 2021.

The ICJ urged that the Draft Act be repealed in its entirety or substantially revised in order to ensure compliance with Thailand’s international legal obligations.

The ICJ is concerned that the law, if adopted, would pose onerous and unwarranted obstacles to many civil society organizations in Thailand, including human rights NGOs, in carrying out their work. In its submission, the ICJ underscores the imprecise and overbroad language of the draft law, which would allow for abusive and arbitrary application by the Thai authorities on “Not-for-Profit Organizations” (NPOs). In particular, it provides for discriminatory restrictions on organizations that receive foreign funding.

“It is well-established in international law and standards that any registration of NPOs should be voluntary and that no law should outlaw or delegitimize activities in defence of human rights on account of the origin of funding,” said Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director.

Violators of the Draft Act would risk having their registration revoked. The Draft Act also imposes liability of criminal punishment on those who operate without registration with imprisonment not exceeding five years or fined not exceeding 100,000 THB (approx. 3,200 USD), or both.

“In cases of registration revocation, the legal recourse available for NPOs to challenge such decisions involves lengthy and burdensome administrative and judicial proceedings, which would normally take years to reach a conclusion. Proceedings of this kind will be untenable for some organizations and will deal a fatal blow to the essential work of many human rights defenders,” said Ian Seiderman.

The Draft Act also provides sweeping powers to government authorities to monitor activities, search and seize electronic data of NPOs without any court warrant, in violation of the rights to privacy.

Background

Thailand is a State party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which requires States to respect and protect, inter alia, the right to freedom of association, expression, peaceful assembly, the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs, the right to privacy and the right to an effective remedy. Thailand may impose limitations on NPOs only in narrow circumstances and subject to strict conditions as set out in the ICCPR.

On 23 February 2021, Thai Cabinet approved in principle the Office of the Council of State’s proposal to enact a law aims to provide oversight on NPOs’ operations.

The draft law is currently under consideration of the Council of State for legal review. Public consultation is currently carried out by the Office, only via their online platform. Members of the public were expected to have registered any concerns about the Draft Act through the website of the Office, by post or by email, between 12 to 31 March 2021 – a considerably tight period of time.

The draft law will then be resubmitted to the Cabinet, then presented to the Parliament.

Download

Recommendations in English and Thai (PDF)

Mar 30, 2021 | News

The ICJ today called for the reform of the country’s law on contempt of court to prevent their abuse and for the withdrawal of the contempt action filed against human rights lawyer Charles Hector.

Charles Hector faces potential contempt of court charges over a letter he sent to an officer of the Jerantut District Forest Office, as part of trial preparation. He is currently representing eight inhabitants of Kampung Baharu, a village in Jerantut, Pahang, in their civil lawsuit against two logging companies, Beijing Million Sdn Bhd and Rosah Timber & Trading Sdn Bhd.

The companies applied for leave to commence contempt of court proceedings against Charles Hector and the defendants. They claim that his letter violates an interlocutory injunction order prohibiting the villagers and their representatives from interfering with or causing nuisance to their work.

“Charles Hector is being harassed and intimidated through legal processes for carrying out his professional duties as a lawyer and gathering evidence in preparation for trial. The Malaysian authorities must act to protect human rights lawyers from sanctions and the threat of sanctions for the legitimate performance of their work,” said Ian Seiderman, the ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director.

The harassment of Charles Hector through legal processes violates international standards such as the UN Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers that make clear that lawyers must be able to perform their professional functions without intimidation, hindrance, harassment or improper interference.

Contempt of court, whether civil or criminal, may result in imprisonment and fines. Malaysia’s contempt of court offense is a common law doctrine and not codified statutorily.

“Fear of contempt charges stands to cast a chilling effect on the work of human rights lawyers and defenders. This further reinforces how Malaysia’s contempt of court doctrine needs to be urgently reformed as it is incompatible with international human rights law and standards,” said Seiderman.

The ICJ calls for the reform of Malaysia’s contempt of court doctrine to ensure clarity in definition, consistency in procedural rules and sentencing limits pertaining to criminal contempt cases. This reform should be in line with recommendations by the Malaysian Bar that the law of contempt be codified statutorily to provide clear and unequivocal parameters as to what really constitutes contempt.

Background

In September 2019, the two logging companies reportedly obtained approvals from the Jerantut District Forest Office to carry out logging in the Jerantut Tambahan Forest Reserve. The eight villagers are from a community many of whose residents have been protesting against the logging. The villagers depend on the forest reserve for clean water and their livelihoods.

On 14 July 2020, the companies filed a writ of summons against the eight villagers in the Kuantan High Court. The writ stated that the plaintiffs had applied for an injunction order to stop the defendants from preventing the companies’ workers from carrying out their works and spreading “false information” online.

On 5 November 2020, the companies successfully obtained an interlocutory injunction order. It was reported that the injunction order prohibits the defendants and their representatives from interfering with the approval given to the plaintiffs by the District Forest Office or causing nuisance to the work of the plaintiffs in any manner whatsoever, including physically, online or by communication with the authorities.

On 17 December 2020 Charles Hector sent a letter on behalf of his clients to Mohd Zarin Bin Ramlan, an officer of the Jerantut District Forestry Office, seeking clarifications on a letter sent by the office on 20 February 2020.

The logging firms contend that the letter violated the injunction order. In January 2021, the companies filed an ex parte application for leave to commence contempt of court proceedings against Charles Hector and the eight villagers.

The hearing was postponed until 25 March 2021 at the Kuantan High Court. On 25 March 2021, the plaintiff’s lawyer opposed the presence and participation of Charles Hector’s lawyer on the grounds that it was an ex parte application, which was contested by Charles Hector’s lawyer. The Court decided to adjourn the hearing to 6 April 2021.

Contact

Boram Jang, International Legal Adviser, e: boram.jang(a)icj.org

Mar 29, 2021 | Advocacy, News

On 25 March 2021, the ICJ filed two submissions to the UN Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) ahead of the review of Thailand’s human rights record in November 2021.

For this particular review cycle, the ICJ made two joint UPR submissions to the Human Rights Council.

In the joint submission by ICJ and Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR), the organizations provided information and analysis to assist the Working Group on the UPR to make recommendations addressing various human rights concerns that arise as a result of Thailand’s failure to guarantee, properly or at all, a number of civil and political rights, including with respect to:

- Constitution and Legal Framework: concerning the 2017 Constitution that continues to give effect to some repressive orders issued by the military junta after the 2014 coup d’état, the Emergency Decree, the Martial Law, and the Internal Security Act;

- Freedom of Expression and Assembly: concerning the use of laws that are not human rights compliant and, as such, arbitrarily restrict the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly, in the context of the Thai government’s response to the pro-democracy protests and, purportedly, to COVID-19; and

- Right to Life, Freedom from Torture and Enforced Disappearance: concerning the resumption of death penalty, the failure to undertake prompt, thorough and impartial investigations, and to ensure accountability of those responsible for the commission of torture, other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance, and the failure, to date, to enact domestic legislation criminalizing torture, other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance.

In the second, joint submission by ICJ, ENLAWTHAI Foundation and Land Watch Thai, the organizations provided information and analysis to assist the Working Group to make recommendations addressing various human rights concerns that arise as a result of Thailand’s failure to guarantee, properly or at all, a number of economic, social and cultural rights, including with respect to:

- Human Rights Defenders: concerning threats and other human rights violations against human rights defenders, and the restrictions on civil society space and on the ability to raise issues that the government deems as criticism of its conduct or that it otherwise disfavours;

- Constitution and Legal Framework: concerning the continuing detrimental impact of the legal framework imposed since the 2014 coup d’état on economic, social and cultural rights;

- Community Consultation: concerning the lack of participatory mechanisms and consultations, as well as limited access to information, for affected individuals and communities in the execution of economic activities that adversely impact local communities’ economic, social and cultural rights;

- Land and Housing: concerning issues relating to access to land and adequate housing, reports of large-scale evictions without appropriate procedural protections as required by international law, and the denial of the traditional rights of indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands and natural resources; and

- Environment: concerning the widespread and well-documented detrimental impacts of hazardous and industrial wastes on the environment, the lack of adequate legal protections for the right to health and the environment, and the effectiveness of the environmental impact assessment process set out under Thai laws.

The ICJ further called upon the Human Rights Council and the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review to recommend that Thailand should take various measures to immediately cease all aforementioned human rights violations; ensure adequate legal protection against such violations; ensure the rights to access to justice and effective remedies for victims of such violations; and ensure that steps be taken to prevent any future violations.

Download

UPR Submission 1 (PDF)

UPR Submission 2 (PDF)

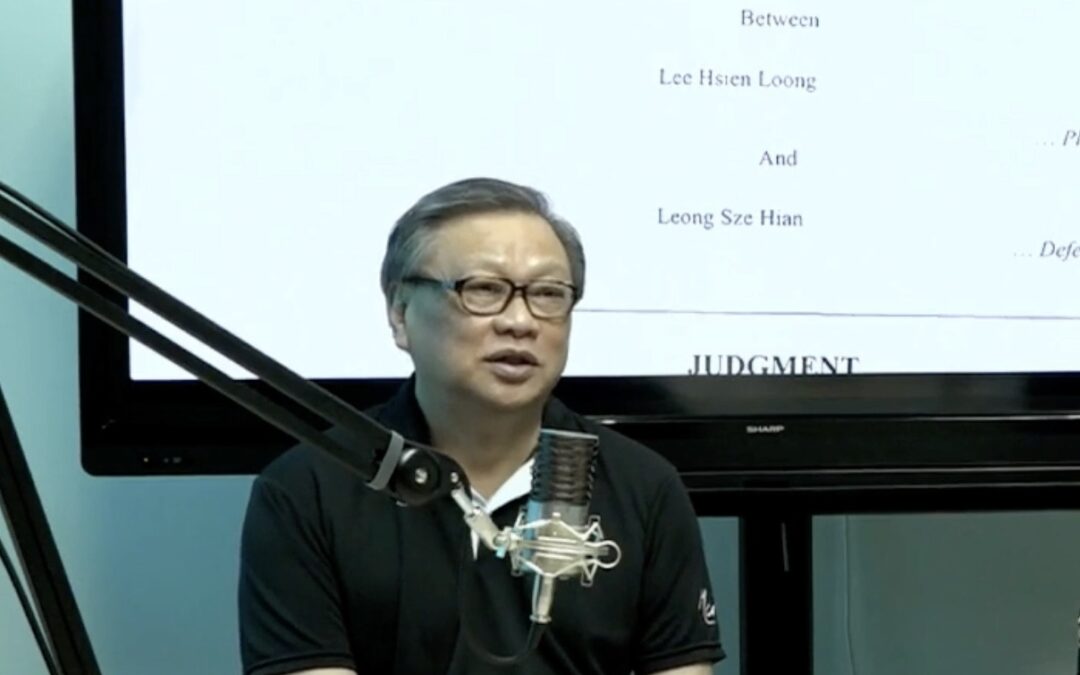

Mar 24, 2021 | News

The High Court of Singapore decision ordering a blogger to pay the Prime Minister thousands of dollars in a defamation suit continues the country’s troubling trend of restricting online freedom of expression, the ICJ said today.

Mar 18, 2021 | News

The ICJ today condemned Sri Lanka’s new ‘de-radicalization’ regulations, which allow for the arbitrary administrative detention of people for up to two years without trial. The regulations could disproportionately target minority religious and ethnic communities.

Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa promulgated Prevention of Terrorism (De-radicalization from holding violent extremist religious ideology) Regulations No. 01 of 2021, which was publicized by way of gazette notification on 12 March, 2021. The “regulations”, which were dictated by the executive without the engagement of Parliament, would send individuals suspected of using words or signs to cause acts of “religious, racial or communal violence, disharmony or feelings of ill will” between communities to be “rehabilitated” at “reintegration centres” for up to two years without trial.

“These regulations, which have been dictated by executive fiat, allow for effective imprisonment of people without trial and so are in blatant violation of Sri Lanka’s international legal obligations and Sri Lanka’s own constitutional guarantees under Article 13 of the Sri Lankan Constitution.”

– Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director

Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Sri Lanka is a party, provides for a number of procedural guarantees for any person deprived of their liberty, many of which are absent in the Regulation. Administrative detention of the kind contemplated under the Regulations, is not permitted, as affirmed repeatedly by the UN Human Rights Committee.

Even prior to the promulgation of the new regulations under Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act No. 48 of 1979 (PTA), Sri Lankan authorities had already been invoking the PTA and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Act, No. 56 of 2007 (enacted to incorporate certain provisions of the ICCPR into domestic law) effectively to persecute people from minority communities. Yet little or no action has been taken by the authorities against those inciting hatred or violence against minorities.

“The new regulations are likely to be used as a bargaining tool where the option is given to a detainee to choose between a year or two spent in “rehabilitation” or detention and trial for an indeterminate period of time, instead of a fair trial on legitimate charges.”

– Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director

Contact

Osama Motiwala, Communications Officer – osama.motiwala@icj.org

Background

Section 3(1) of the ICCPR Act which prohibits advocacy of hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, violence or hostility has hitherto been misused to target members of minority communities. In April 2020, Ramzy Razeek, a retired government employee, was arrested for a Facebook post calling for an ideological ‘jihad’ against the policy of mandatory cremation of people who had died as a result of Covid-19. He was detained under the ICCPR Act for more than five months and finally released on bail due to medical reasons in September 2020.

In May 2020, Ahnaf Jazeem, a young Muslim poet, was arrested under the PTA in connection with a collection of poems he had published in the Tamil language, which were apparently misinterpreted by Sinhalese authorities to be read as containing extreme messages. Just last week, a few days after the promulgation of the new regulations, Ahnaf’s lawyers expressed alarm that both Ahnaf and his father were being pressured to make admissions that he had engaged in teaching ‘extremism’. The ICJ had previously raised concerns about the arbitrary arrest and prolonged detention of Human Rights lawyer Hejaaz Hizbullah. After being detained under the PTA for 10 months without being given reason for his arrest, he is now being tried for speech-related offences under the PTA and ICCPR Act.

The ICJ has consistently called for the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act, which has been used to arbitrarily detain suspects for months and often years without charge or trial, facilitating torture and other abuse. The ICJ reiterates its call for the repeal and replacement of this vague and overbroad anti-terror law and regulations brought under it, in line with Sri Lanka’s international obligations.

The new PTA regulations require those who surrender or are arrested on suspicion of using words or signs to cause acts of violence, disharmony or ill will between communities to be handed over to the nearest Police Station within 24 hours after which a report is to be submitted by the Police to the Defence Minister (the position is currently held by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa) to consider whether the suspect should be detained further. The regulations would also apply to those who had surrendered or been taken into custody under the PTA, the Prevention of Terrorism (Proscription of Extremist Organizations) Regulations No. 1 of 2019 and the Emergency (Miscellaneous Provisions and Powers) Regulation, No. 1 of 2019.

The Attorney General is given the power to decide if a suspect should be tried for a specific offence or be send to a rehabilitation centre as an alternative. If the decision is to rehabilitate, the suspect would be produced before a Magistrate with the written consent of the Attorney General. The Magistrate may thereafter order that the suspect be referred to a rehabilitation centre for a period not exceeding one year. Such period can be extended by a period of six months at a time up to one more year by the Minister upon the recommendation of the Commissioner-General for Rehabilitation. The regulations further state that the Commissioner–General should provide the detainee with psycho-social assistance and vocational and other training during the rehabilitation period to ensure reintegration into society. The regulations also provide that such detainee may with the permission of the officer in charge of the Centre be entitled to meet their parents, relations or guardian once every two weeks.