Mar 15, 2018 | News

The ICJ called on the Government of Singapore to halt the impending execution of Hishamrudin bin Mohd, and take immediate steps to impose a moratorium on executions, with a view towards the abolition of the death penalty in the near future.

Hishamrudin bin Mohd, a Singaporean national, was sentenced to death in 2016, under mandatory sentencing laws, after being convicted of possessing drugs for the purpose of trafficking.

His execution is scheduled to take place on 16 March 2018.

The ICJ opposes the death penalty in all circumstances as a denial of the right to life and a form of cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment.

“Singapore, as this year’s Chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, must use this opportunity to lead the way in the region in recognizing that the death penalty is inherently incompatible with human dignity and a violation of human rights,” Sam Zarifi, ICJ Secretary General said.

“Singapore should set an example to other ASEAN Member States in upholding the rule of law and protecting human rights,” he added.

Furthermore, the ICJ expressed serious concern that Singapore still applies the mandatory death penalty, including for drug offenses which, according to international standards does not the meet the threshold of “most serious crimes” to which the death penalty must be confined.

“States that have not yet abolished the death penalty should never apply them for drug offenses nor make them automatic,” Zarifi said.

The UN Special Rapporteurs on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions have stated that under no circumstances should death penalty be mandatory.

International human rights law is undermined when mandatory death penalty is imposed since sentencing must reflect assessment of the factors in each case to ensure that the defendant’s human rights and the narrow limits on the use of death penalty have been respected.

The ICJ notes that the UN General Assembly has adopted repeated resolutions with the support of the overwhelming majority of States, most recently in December 2016 calling for an international moratorium on the use of death penalty with a view to abolition.

Presently, some 170 States around the world have either abolished the death penalty or put a moratorium to its use.

The UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres emphasized that “the death penalty has no place in the 21st century.”

Contact

Emerlynne Gil, Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, t: +662 619 8477 (ext. 206); e: emerlynne.gil(a)icj.org

Background

Hishamrudin bin Mohd, a Singaporean national, was found guilty of possessing 34.94 grams of diamorphine, allegedly for the purpose of trafficking. His appeal was rejected on 3 July 2017 and his execution was scheduled on 16 March 2018.

The ICJ received information that Hishamrudin bin Mohd filed a last-minute application for judicial review on 12 March 2018 and a closed-door hearing was set on 14 March 2018. However, on 15 March 2018, the Court of Appeal denied his appeal.

Mar 14, 2018 | News

On 12 and 13 March 2018, the ICJ participated in and presented at a workshop for Cambodian civil society on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR).

The workshop was organized by the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR), UPR Info and the Cambodia Country Office of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

This workshop aimed to prepare participants ahead of the deadline for civil society submissions to the UPR in July 2018.

The Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) will undergo the third cycle of its UPR in January 2019.

The objectives of the workshop were to:

- 1. Introduce the UPR to newcomers, identifying where the UPR fits within the UN’s human rights framework and demonstrating how civil society organizations (CSOs) can utilize the UPR to further their human rights objectives;

- 2. Share experiences of national stakeholders in the UPR process and discuss developments since the second cycle and priorities for the third cycle;

- 3. Learn from the experiences of CSOs in the region on developing UPR CSO submissions;

- 4. Provide technical training regarding the drafting of UPR CSO submissions;

- 5. Establish thematic groups to begin developing joint submissions and establish a timeline for the drafting process.

On 12 March 2018, Kingsley Abbott, Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia for the ICJ, delivered a presentation on submissions drafting and advocacy techniques for the UPR and also spoke about the experiences of CSOs in Thailand in developing UPR CSO submissions.

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, e: kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

Mar 13, 2018 | News

On 12 March 2018, the ICJ co-hosted the forum “14 Years after Somchai’s Disappearance, What Have We Learned?” to commemorate the 14th anniversary of the enforced disappearance of prominent lawyer and human rights defender Somchai Neelapaijit.

The forum was held at the Faculty of Law in Thammasat University’s Tha Pra Chan campus.

More than 80 participants attended the event, including alleged torture victims, family victims of torture and enforced disappearance, students, lecturers, lawyers, civil society organizations, diplomats, members of the Thai authorities and media.

The objectives of the forum were to (i) mark the 14th anniversary of the enforced disappearance of Somchai Neelapaijit and the lack of progress in the investigation (ii) raise awareness and discuss the latest amendments to the Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearances Act (‘Draft Act’) and its deficiencies; and (iii) discuss the newly constituted Committee managing complaints of torture and enforced disappearance, which was established by the Prime Minister on 23 May 2017.

Opening remarks were delivered by Angkhana Neelapaijit, wife of Somchai Neelapaijit, and Laurent Meillan, OHCHR’s Deputy Regional Representative.

Sanhawan Srisod, the ICJ’s National Legal Advisor, spoke during the first panel discussion on recent amendments to the Draft Act, which was moderated by Poonsuk Poonsukcharoen from Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) and also included the following panelists:

- Nongporn Rungpetchwong, Human Rights Expert, Rights and Liberties Protection Department, Ministry of Justice

- Assistant Professor Dr. Ronnakorn Bunmee, Faculty of Law, Thammasat University

- Somchai Homlaor, Lawyer and Senior Advisor to Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF)

The second panel discussion on the roles and duties of the Committee Managing Complaints for Torture and Enforced Disappearance Cases was moderated by. Yingcheep Atchanont from Internet Law Reform Dialogue (iLaw) and included the following speakers:

- Manunpan Rattanacharoen, Office of Foreign Affairs and International Crimes, Department of Special Investigation (DSI), Ministry of Justice

- Professor Narong Jaihan, Chair, Sub-committee on Prevention of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Cases

- Angkhana Neelapaijit, Family of “disappeared” person

- Isma-ae Tae, Alleged victim of torture and ill-treatment

During the event, the ICJ also highlighted its open letter to Thailand’s Minister of Justice, dated 12 March 2018, on the recent amendments to the Draft Act, which sets out concerns that the recent amendments would, if adopted, fail to bring the law into compliance with Thailand’s international human rights obligations.

The forum was co-organized with the Neelapaijit family, Thammasart University’s Faculty of Law, Amnesty International Thailand, Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF), together with the United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Regional Office for South East Asia.

Read also

ICJ and Amnesty International, Open letter to Thailand’s Minister of Justice on the amendments to the Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearances Act, 12 March 2018

English

Thai

ICJ and Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, Joint submission to the UN Committee against Torture, 29 January 2018

ICJ and Amnesty International, Recommendations to Thailand’s Ministry of Justice on the Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearances Act, 23 November 2017

To mark the 10-year anniversary of Somchai Neelapaijit’s ‘disappearance’, the ICJ released a report documenting the tortuous legal history of the case, Ten Years Without Truth: Somchai Neelapaijit and Enforced Disappearances in Thailand, 7 March 2014

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, e: kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

Thailand-Amendments-to-Prevention-and-Suppression-of-Torture-2018-ENG (Full text in ENG, PDF)

Thailand-Amendments-to-Prevention-Suppression-of-Torture-2018-THA (Full text in THA, PDF)

Mar 9, 2018 | Events, News

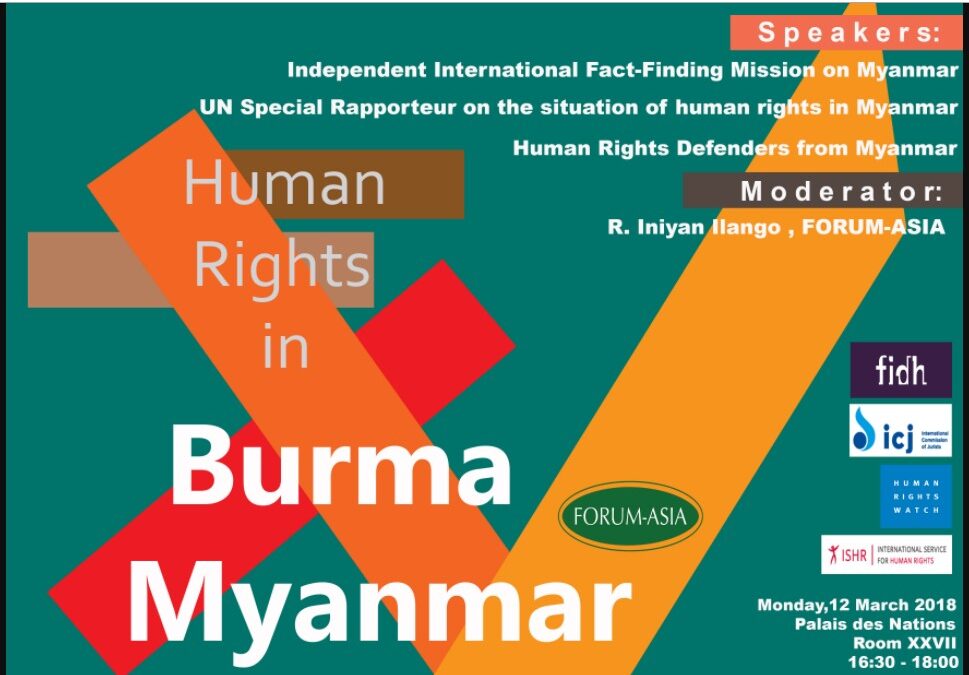

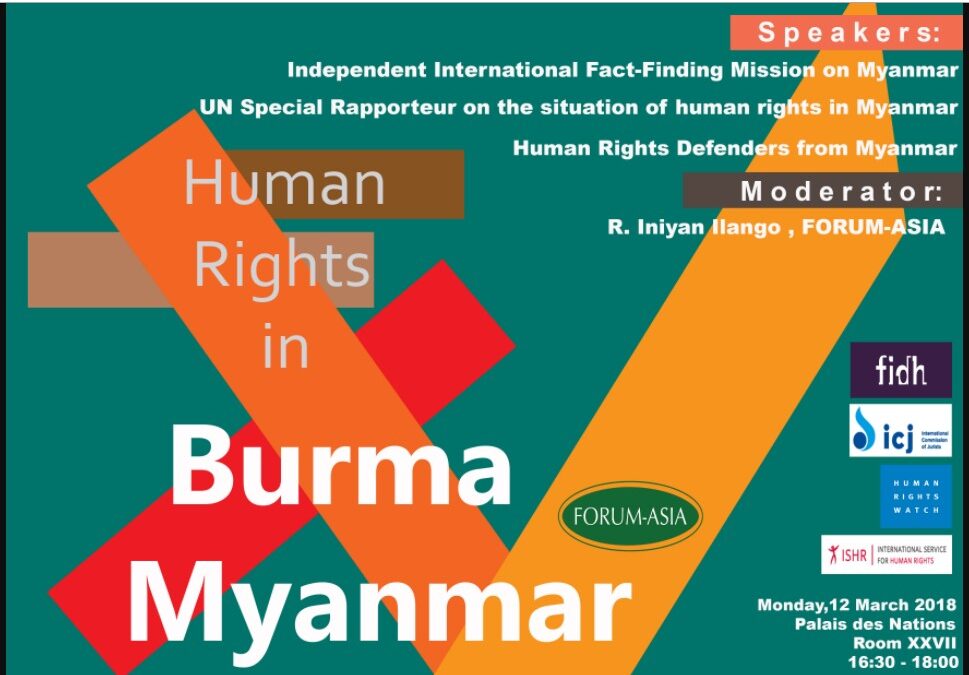

This side event at the Human Rights Council takes place on Monday, 12 March, 16:30-18:00, room XXVII of the Palais des Nations. It is organized by Forum-Asia, and co-sponsored by the ICJ.

Speakers:

Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar

UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar

Human Rights Defenders from Myanmar

Moderator:

R. Iniyan Ilango, Forum – Asia

Feb 27, 2018 | Events, News

The ICJ, in collaboration with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Regional Office for South-East Asia (OHCHR), and the Centre for Civil and Political Rights, organised a workshop for lawyers from southeast Asia, on engaging with UN human rights mechanisms.

The two-day workshop provided some thirty lawyers from Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Lao PDR with knowledge, practical skills and expert advice about UN human rights mechanisms, with the participants themselves sharing their own experiences and expertise.

In addition to explaining what the UN mechanisms are and how they work, the workshop discussed how lawyers can use the outputs of UN human rights mechanisms in their professional activities, as well as how to communicate with and participate in UN human rights mechanisms in order to ensure good cooperation and to best serve the interests of their clients.

Sessions were introduced by presentations by the ICJ’s Main Representative to the United Nations in Geneva and OHCHR officials, followed by discussions and practical exercises in which all participants were encouraged to contribute questions and their own observations.

A special discussion of effective engagement of lawyers with Treaty Bodies was led by Professor Yuval Shany, a member of the Human Rights Committee established to interpret and apply the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

The workshop also aimed to encourage the building of relationships and networks between the lawyers from across the region.

The workshop forms part of a broader project of awareness-raising and capacity-building for lawyers from the region, about UN mechanisms.

A similar workshop was held in January 2017 for lawyers from Myanmar.

The project has also published (unofficial) translations of key UN publications into relevant languages, and is hosting lawyers in a mentorship programme in Geneva.

More details are available by contacting UN Representative Matt Pollard (matt.pollard(a)icj.org) or by clicking here: https://www.icj.org/accesstojusticeunmechanisms/

Feb 15, 2018 | News

Thailand should immediately cease misusing criminal and civil defamation laws to legally harass victims, human rights defenders and journalists who raise allegations of torture or other ill-treatment, the ICJ said today.

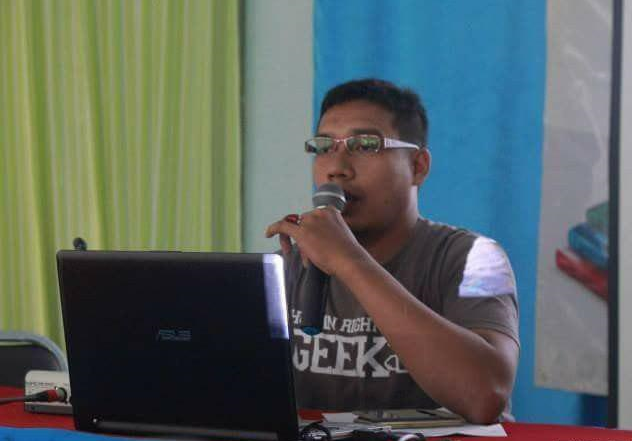

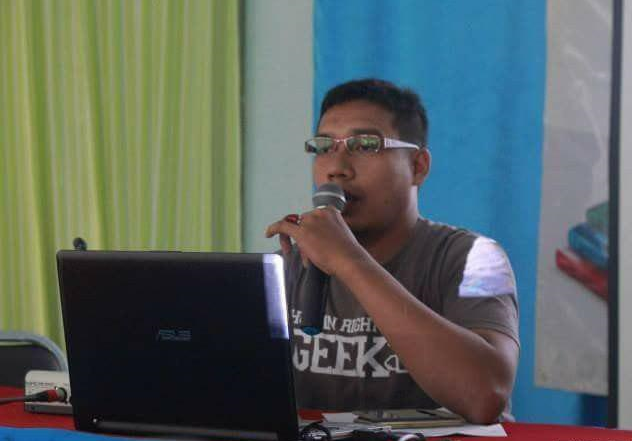

Yesterday, the Director of the Internal Operations Security Command (ISOC) Region 4, Lt. Gen. Piyawat Nakwanich, reportedly authorized Lt. Col. Seathtasit Kaewkumuang to lodge defamation complaints against Isma-ae Tae, a founder of Patani Human Rights Organization (HAP).

ISOC is responsible for security operations in Thailand’s deep South.

“It is astonishing that after all of the Government’s repeated commitments to address allegations of torture and protect victims and human rights defenders, ISOC is now misusing the justice system to legally harass an alleged victim of torture,” said Kingsley Abbott, the ICJ’s Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia.

“Thailand should immediately stop these defamation complaints against Isma-ae Tae and ensure an investigation that meets international law and standards is conducted into all allegations of torture or other ill-treatment without delay,” he added.

The accusations relate to a TV program entitled “Policy by People” that aired on the Thai PBS channel on 5 February 2018 in which Isma-ae Tae described being tortured and ill-treated by Thai soldiers when he was a student in Yala, located in Thailand’s restive deep South.

Criminal defamation in Thailand carries a maximum penalty of two years imprisonment and a fine of up to 200,000 Baht (USD $6,300).

The imposition of harsh penalties such as imprisonment or large fines under these laws has the effect of discouraging victims of torture or other ill-treatment from coming forward to seek the remedies and reparations to which they are entitled under international human rights law binding on Thailand, the ICJ said.

The complaints were made against the backdrop of a ruling by the Supreme Administrative Court on 19 October 2016, which ordered the Royal Thai Army and the Defence Ministry to pay 305,000 baht (USD $9,700) compensation to Isma-ae Tae, after it found he was “physically assaulted” during detention and had been illegally detained for nine days – exceeding the limit of seven days permitted under Martial Law Act B.E. 2457 (1914) (Martial Law).

“Even more astonishing is that a superior Thai court has already found that the military physically assaulted Isma-ae Tae and awarded him compensation, which only serves to highlight the injustice of these complaints”, added Abbott.

In 2008, Isma-ae Tae was arrested pursuant to Martial Law and allegedly tortured in order to purportedly extract a confession in relation to a national security case. To date, no perpetrators have been brought to justice.

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, Senior International Legal Adviser, ICJ Asia Pacific Programme, t: +66 94 470 1345, e: kingley.abbott@icj.org

Thailand-Isma-ae Tae defamation case-News-Press releases-2018-ENG (full story with additional information, in PDF)

Thailand-Isma-ae Tae defamation case-News-Press releases-2018-THA (Thai version of full sory, in PDF)

Read also

Thailand: ICJ welcomes decision to end proceedings against human rights defenders who raised allegations of torture

Thailand: ICJ welcomes dropping of complaints against human rights defenders but calls for investigation into torture

Thailand: stop use of defamation charges against human rights defenders seeking accountability for torture

Thailand: immediately withdraw criminal complaints against human rights defenders

Further reading on the Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Act

UN Committee against Torture: ICJ and TLHR’s joint submission on Thailand

Thailand: ICJ, Amnesty advise changes to proposed legislation on torture and enforced disappearances

Thailand: ICJ commemorates international day in support of victims of enforced disappearances

Thailand: pass legislation criminalizing enforced disappearance, torture without further delay