Mar 14, 2018 | News

On 12 and 13 March 2018, the ICJ participated in and presented at a workshop for Cambodian civil society on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR).

The workshop was organized by the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR), UPR Info and the Cambodia Country Office of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

This workshop aimed to prepare participants ahead of the deadline for civil society submissions to the UPR in July 2018.

The Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) will undergo the third cycle of its UPR in January 2019.

The objectives of the workshop were to:

- 1. Introduce the UPR to newcomers, identifying where the UPR fits within the UN’s human rights framework and demonstrating how civil society organizations (CSOs) can utilize the UPR to further their human rights objectives;

- 2. Share experiences of national stakeholders in the UPR process and discuss developments since the second cycle and priorities for the third cycle;

- 3. Learn from the experiences of CSOs in the region on developing UPR CSO submissions;

- 4. Provide technical training regarding the drafting of UPR CSO submissions;

- 5. Establish thematic groups to begin developing joint submissions and establish a timeline for the drafting process.

On 12 March 2018, Kingsley Abbott, Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia for the ICJ, delivered a presentation on submissions drafting and advocacy techniques for the UPR and also spoke about the experiences of CSOs in Thailand in developing UPR CSO submissions.

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, e: kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

Mar 13, 2018 | News

On 12 March 2018, the ICJ co-hosted the forum “14 Years after Somchai’s Disappearance, What Have We Learned?” to commemorate the 14th anniversary of the enforced disappearance of prominent lawyer and human rights defender Somchai Neelapaijit.

The forum was held at the Faculty of Law in Thammasat University’s Tha Pra Chan campus.

More than 80 participants attended the event, including alleged torture victims, family victims of torture and enforced disappearance, students, lecturers, lawyers, civil society organizations, diplomats, members of the Thai authorities and media.

The objectives of the forum were to (i) mark the 14th anniversary of the enforced disappearance of Somchai Neelapaijit and the lack of progress in the investigation (ii) raise awareness and discuss the latest amendments to the Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearances Act (‘Draft Act’) and its deficiencies; and (iii) discuss the newly constituted Committee managing complaints of torture and enforced disappearance, which was established by the Prime Minister on 23 May 2017.

Opening remarks were delivered by Angkhana Neelapaijit, wife of Somchai Neelapaijit, and Laurent Meillan, OHCHR’s Deputy Regional Representative.

Sanhawan Srisod, the ICJ’s National Legal Advisor, spoke during the first panel discussion on recent amendments to the Draft Act, which was moderated by Poonsuk Poonsukcharoen from Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) and also included the following panelists:

- Nongporn Rungpetchwong, Human Rights Expert, Rights and Liberties Protection Department, Ministry of Justice

- Assistant Professor Dr. Ronnakorn Bunmee, Faculty of Law, Thammasat University

- Somchai Homlaor, Lawyer and Senior Advisor to Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF)

The second panel discussion on the roles and duties of the Committee Managing Complaints for Torture and Enforced Disappearance Cases was moderated by. Yingcheep Atchanont from Internet Law Reform Dialogue (iLaw) and included the following speakers:

- Manunpan Rattanacharoen, Office of Foreign Affairs and International Crimes, Department of Special Investigation (DSI), Ministry of Justice

- Professor Narong Jaihan, Chair, Sub-committee on Prevention of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Cases

- Angkhana Neelapaijit, Family of “disappeared” person

- Isma-ae Tae, Alleged victim of torture and ill-treatment

During the event, the ICJ also highlighted its open letter to Thailand’s Minister of Justice, dated 12 March 2018, on the recent amendments to the Draft Act, which sets out concerns that the recent amendments would, if adopted, fail to bring the law into compliance with Thailand’s international human rights obligations.

The forum was co-organized with the Neelapaijit family, Thammasart University’s Faculty of Law, Amnesty International Thailand, Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF), together with the United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Regional Office for South East Asia.

Read also

ICJ and Amnesty International, Open letter to Thailand’s Minister of Justice on the amendments to the Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearances Act, 12 March 2018

English

Thai

ICJ and Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, Joint submission to the UN Committee against Torture, 29 January 2018

ICJ and Amnesty International, Recommendations to Thailand’s Ministry of Justice on the Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearances Act, 23 November 2017

To mark the 10-year anniversary of Somchai Neelapaijit’s ‘disappearance’, the ICJ released a report documenting the tortuous legal history of the case, Ten Years Without Truth: Somchai Neelapaijit and Enforced Disappearances in Thailand, 7 March 2014

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, e: kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

Thailand-Amendments-to-Prevention-and-Suppression-of-Torture-2018-ENG (Full text in ENG, PDF)

Thailand-Amendments-to-Prevention-Suppression-of-Torture-2018-THA (Full text in THA, PDF)

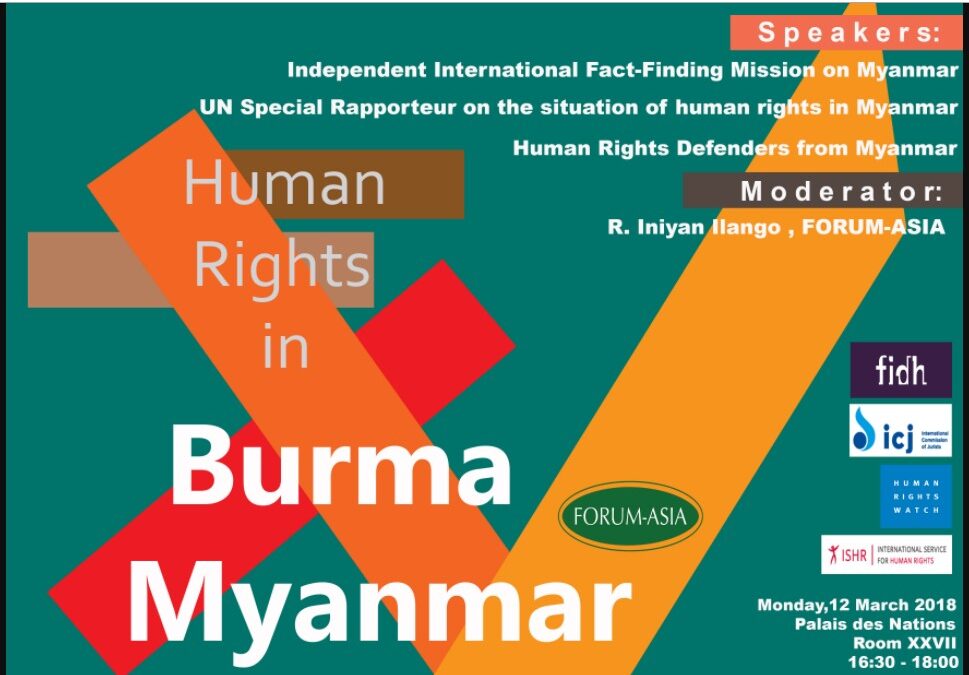

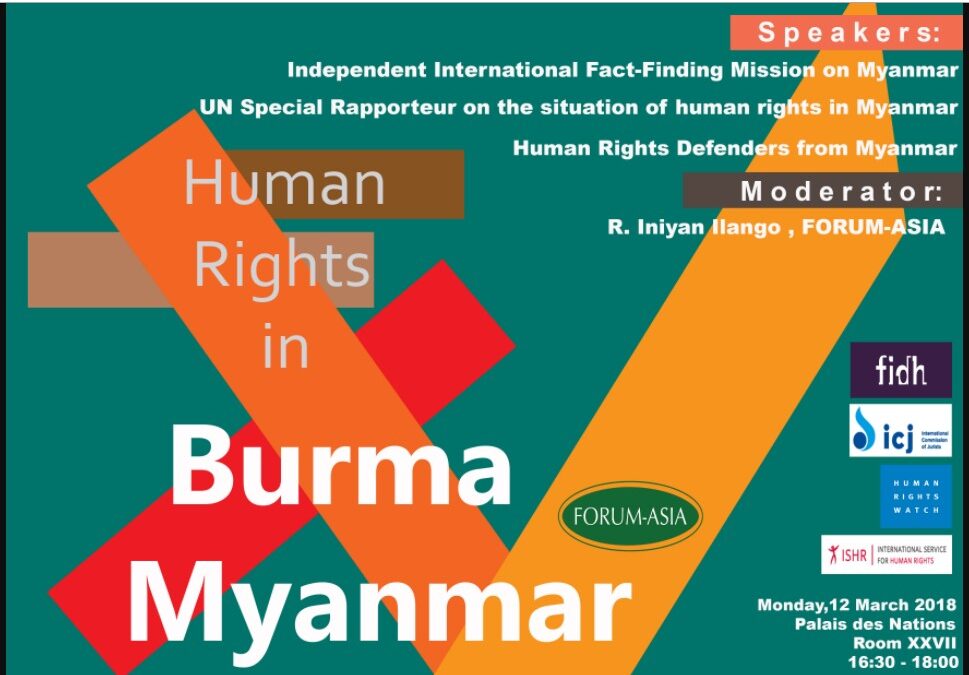

Mar 9, 2018 | Events, News

This side event at the Human Rights Council takes place on Monday, 12 March, 16:30-18:00, room XXVII of the Palais des Nations. It is organized by Forum-Asia, and co-sponsored by the ICJ.

Speakers:

Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar

UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar

Human Rights Defenders from Myanmar

Moderator:

R. Iniyan Ilango, Forum – Asia

Mar 8, 2018 | Multimedia items, News, Video clips

Today on International Women’s Day the world looks to celebrate the achievements of women and advances made towards the realization of women’s human rights but the day is also an opportunity to address the issues that continue to disadvantage women.

In the 70th anniversary year of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights many women around the world have seen States failing to live up to their obligations to ensure that they are able to exercise their human rights.

Where women’s human rights are violated many women face discrimination, denial of equal protection of the law and other impediments in accessing the justice that they deserve.

“The ICJ has a strong commitment to addressing the obstacles women face in accessing justice,” said ICJ Acting Vice-President, Justice Radmila Dragicevic-Dicic.

“The judiciary has an important role in protecting the rights of women, but in many States there is a lack of proper awareness and understanding of issues such as gender based-violence. Many judges would benefit from judicial education on specific gender-based issues to ensure that women victims are made visible and their rights protected by domestic laws and relevant international standards,” she added.

For several years the ICJ has worked on women’s access to justice issues in different countries in all regions with a variety of stakeholders, including human rights defenders, lawyers, judges, governmental authorities and international rights experts and mechanisms.

For example, in Tunisia, the ICJ issued a memorandum calling on authorities to remove the obstacles women face in accessing justice.

The ICJ has held regional dialogues in Africa and Asia with judges and lawyers.

In Asia, one outcome of this was The Bangkok General Guidance for Judges in Applying a Gender Perspective, designed to assist judges in employing a gender perspective in deciding cases before them, which has since been adopted for use by judiciaries in Indonesia and the Philippines.

In Africa, the need for gendered perspectives in judicial decision-making was also raised in a regional report evaluating sexual and gender based violence (SGBV) and fair trial rights.

The ICJ has undertaken substantial work on women’s access to justice in the context of SGBV, including a report calling for an eradication of harmful gender stereotypes and assumptions and a Practitioners’ Guide on Women’s Access to Justice for Gender-Based Violence.

Both have been used as training tools in Asia, Africa and MENA, most recently at a workshop on SGBV in Swaziland.

Last year the ICJ released a memorandum on effective investigation and prosecution of SGBV in Morocco.

The ICJ has also undertaken trial observations during hearings in the landmark Sepur Zarco case, the first case that resulted in a conviction for sexual crimes that had occurred during Guatemala’s internal conflict in the early 1980s.

The ICJ regularly engages with the UN Human Rights Council and the UN Committee on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women to highlight issues around women’s access to justice and call on the international community to be vigilant in upholding women’s rights protections.

“The ICJ is lucky to count among its number some very impressive women human rights defenders, who bring a great deal of expertise to the work of the organization,” said Dragicevic-Dicic.

“The five most recent additions to the ICJ have further strengthened the organization’s ability to speak authoritatively on women’s rights, and I look forward to working with my new colleagues to enhance women’s access to justice,” she added.

The new additions to the ICJ include Dame Silvia Cartwright, Former Governor of New Zealand; Professor Sarah Cleveland, Constitutional and Human Rights Professor at Columbia Law School in the USA; Justice Martine Comte who has over 30 years judicial experience in France; Mikiko Otani, member of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child from Japan; and Justice Lillian Tibatemwa-Ekirikubinza from the Supreme Court of Uganda.

In an interview with the ICJ, Commissioner Justice Elizabeth Evatt, a distinguished Australian lawyer, jurist and trailblazer for women in the legal profession in her country, spoke about the importance of women being able to access justice.

One of the architects of Australia’s Family Law Act of 1975, Justic Evatt told the ICJ how the Act made divorce more accessible and abolished the Common Law relics that gave men greater rights over women, however new problems have emerged since then.

Justice Evatt explained that “(the Act) was an extremely important reform for women. It made it far easier for men and women to access divorce and have their matters dealt with because the court had conciliation and counselling services and also legal aid was more readily available. But I am afraid that since those days, thing have changed. The Family Court is now beset with delays and obstacles and it is impossible for people to get legal aid. People have to take their case on their own or face huge legal costs, so having begun well, it hasn’t continued well. More resources are needed.”

Justice Evatt also considers that there is a need for the government and the judiciary to take more action to address domestic violence.

However, she noted, “there has been a change over the years with a growing awareness of both the police and the local courts, which are the main ones dealing with violence. They have become far more aware of the need to take action to protect women and prevent violence but the cure for domestic violence does not lie just with the courts but also with the whole of society.”

Watch the interview:

Mar 8, 2018 | News

The Sri Lankan government must act swiftly and in line with human rights to prosecute those responsible for recent communal violence.

Particularly for attacks against the minority Muslim community in Kandy district, while avoiding the abusive practices of the past, said the ICJ today.

Sri Lanka’s President, Maithripala Sirisena, proclaimed an island-wide state of emergency on 6th March 2018, following a curfew imposed in several areas since Monday.

The action came following a spate of attacks against members of the Muslim community that was spreading in the Kandy district, following attacks in Ampara last week, in Gintota in 2016, and Aluthgama in 2014.

“The government must show that it will bring to account those who have incited communal violence, particularly notorious figures who have been emboldened by the pervading impunity to preach hatred openly and publicly. The arrest of key suspects yesterday is a start and convictions must follow,” said Frederick Rawski, ICJ’s Asia director.

“But the government must ensure that its investigation is impartial and effective and follows due process of the law,” he added.

The ICJ called upon the government of Sri Lanka to swiftly prosecute those responsible for inciting and carrying out the communal violence using existing legal provisions in the Penal Code and the ICCPR Act, the latter of which prohibits advocating “national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence.”

The ICJ is concerned that the Emergency Regulations issued by the President through powers under the Public Security Ordinance, confer excessively broad powers on the army and the police to search, arrest and investigate.

“Given Sri Lanka’s experience of Emergency Regulations, the government should ensure that these regulations are time-bound and comply with Sri Lanka’s international human rights obligations, including under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” said Rawski.

The government has further restricted access to selected instant messaging applications and social media platforms “as an extraordinary but temporary response to limit the increasing spread of hate speech and violence through social media websites and phone messaging applications.”

“Blocking social media and other communication channels, even with the best of intentions, typically has the negative effect of restricting affected persons from seeking assistance, journalists from reporting around the situation and may actually undermine efforts to counter violence and hate speech. Any such measures should be narrowly targeted and limited in time,” said Rawski.

“A better approach would be for the Sri Lankan government to aggressively push back against these hateful narratives by demonstrating in actions as well as its rhetoric that Sri Lanka is a diverse country in which all of its citizens’ rights are respected and protected equally,” he added.

Background

Chapter XVIII of the Constitution and the Public Security Ordinance of Sri Lanka empowers the President to make emergency regulations in the interest of ‘public security and the preservation of public order or for the maintenance of supplies and services essential to the life of the community.’ Sri Lanka has a history of governance using emergency powers, which in the past has posed a challenge for democratic governance and human rights, providing law enforcement with wide powers, circumventing ordinary checks and balances.

The President, while justifying circumstances that led to his proclamation of a state of emergency, has stated that he “has given special instructions the Police and the tri-forces to take action in terms of these regulations, in a lawful manner in good faith while ensuring minimum disturbance to the life and well-being of people, in conformity with Fundamental Human Rights of people.”

Feb 27, 2018 | Events, News

The ICJ, in collaboration with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Regional Office for South-East Asia (OHCHR), and the Centre for Civil and Political Rights, organised a workshop for lawyers from southeast Asia, on engaging with UN human rights mechanisms.

The two-day workshop provided some thirty lawyers from Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Lao PDR with knowledge, practical skills and expert advice about UN human rights mechanisms, with the participants themselves sharing their own experiences and expertise.

In addition to explaining what the UN mechanisms are and how they work, the workshop discussed how lawyers can use the outputs of UN human rights mechanisms in their professional activities, as well as how to communicate with and participate in UN human rights mechanisms in order to ensure good cooperation and to best serve the interests of their clients.

Sessions were introduced by presentations by the ICJ’s Main Representative to the United Nations in Geneva and OHCHR officials, followed by discussions and practical exercises in which all participants were encouraged to contribute questions and their own observations.

A special discussion of effective engagement of lawyers with Treaty Bodies was led by Professor Yuval Shany, a member of the Human Rights Committee established to interpret and apply the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

The workshop also aimed to encourage the building of relationships and networks between the lawyers from across the region.

The workshop forms part of a broader project of awareness-raising and capacity-building for lawyers from the region, about UN mechanisms.

A similar workshop was held in January 2017 for lawyers from Myanmar.

The project has also published (unofficial) translations of key UN publications into relevant languages, and is hosting lawyers in a mentorship programme in Geneva.

More details are available by contacting UN Representative Matt Pollard (matt.pollard(a)icj.org) or by clicking here: https://www.icj.org/accesstojusticeunmechanisms/