Aug 20, 2020 | News

Despite remarkable efforts to recover and identify human remains in Latin America, there are still thousands of cases where remains have not been identified and returned to their family. Crucially, families still struggle to understand and participate in the forensic process.

To address this issue, el Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (EAAF) launched today a Forensic Guide which aims at providing practical and accessible information on the investigation, recovery, and analysis of human remains.

Currently, this publication is only available in Spanish but an English version will be provided in the forthcoming months.

The guide will be particularly useful for people who have no previous forensic knowledge and will contribute towards improving the understanding and participation of victims and civil society organizations in the search for disappeared persons.

The Guide was written by Luis Fondebrider, the executive director of the EAAF and takes into account international standards including the revised Minnesota Protocol on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Death (2016).

The ICJ, the Equipo Peruano de Antropología Forense (EPAF) and the Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala (FAFG) provided input during the Guide’s development.

The Guide was launched during a Webinar. The key speakers were Luis Fondebrider from the EAAF; Claudia Rivera from the FAFG and Franco Mora from the EPAF. It was moderated by Carolina Villadiego from the ICJ.

At the launch, all the forensic experts emphasized the central role that the families of disappeared persons must play in the process of investigation, recovery, and analysis of human remains. In particular, it was acknowledged that they not only have key information to find the remains but also, they have driven the processes.

Background

The Guide was produced as part of a regional project addressing justice for extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances in Colombia, Guatemala, and Peru, which is coordinated by the ICJ.

The aim of the project is to promote the accountability of perpetrators and access to effective remedies and reparation for victims and their families in cases of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances in Colombia, Guatemala and Peru – and Latin America more broadly – through effective, accountable and inclusive laws, institutions and practices that also reduce the risk of future violations. The project is supported by the EU European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR).

The ICJ’s partners include the Asociación de Familiares de Detenidos-Desaparecidos de Guatemala (FAMDEGUA), Asociación Red de Defensores y Defensoras de Derechos Humanos (dhColombia), Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (EAAF), Equipo Peruano de Antropología Forense (EPAF), Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala (FAFG), and the Instituto de Defensa Legal (IDL).

Contacts:

Kingsley Abbott, Coordinator of the Global Accountability Initiative, e: kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

Carolina Villadiego, Legal and Policy Adviser, Latin America, and Regional Coordinator of the Project, e: carolina.villadiego(a)icj.org

Aug 19, 2020 | News

Today the ICJ called on the public authorities to refrain from comments or actions that could undermine the integrity of the judicial process and the independence of the judiciary.

On August 4, the Instruction Special Chamber of the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice ordered the pretrial detention, substituted for house arrest, of the former President Álvaro Uribe Velez, relating to allegations of bribery of witnesses and procedural fraud.

In recent days, a number of politicians have made highly inappropriate and inflammatory statements, including some suggesting that judges are making their decisions based on ideological or political biases rather than based on the Constitution and the law.

Colombian president Ivan Duque said in remarks broadcast on television on the 4 of August: “it hurts as a Colombian that many of those who have lacerated the country with barbarism defend themselves at liberty or are even guaranteed to never go to prison, and that an exemplary public servant who has held the highest dignity of the State is not allowed to defend himself in freedom with the presumption of innocence. I am and will always be a believer in the innocence and in the honor of him who, with his example, have earned a place in the history of Colombia.” (unofficial translation).

The ICJ stresses that it is inappropriate for a head-of-State or other executive official to intervene in this manner in a case that is under active judicial proceedings. The UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary make clear that “it is the duty of all governmental and other institutions to respect and observe the independence of the judiciary” and this includes refraining from any “improper influences, inducements, pressures, threats or interferences, direct or indirect.”

In reaction to Senator Uribe’s arrest, the political party “Centro Democrático”, of which both President Duque and former President Uribe are members, released a press statement saying that they were planning to propose a National Constituent Assembly with the purpose of “depoliticizing justice”. Also, former President Uribe mentioned on 16 of August that he hoped his political party would initiate a reform of the justice system through a “referendum” to end the “politicization” of the Court.

The ICJ considers that any actions concerning reforms of the justice sector must be based on the standards and best practices that reinforce the independence of the judiciary and the prompt, timely and fair administration of justice, and not on a political reaction based on a single active case.

Lastly, United States Vice President Mike Pence has also made inappropriate remarks related to the Colombian justice system, tweeting on August 14 that he joined the voices that called Colombian authorities to let Alvaro Uribe “defend himself as a free man”.

Contact

Carolina Villadiego Burbano, ICJ Latin America legal and policy adviser, e: carolina.villadiego(a)icj.org

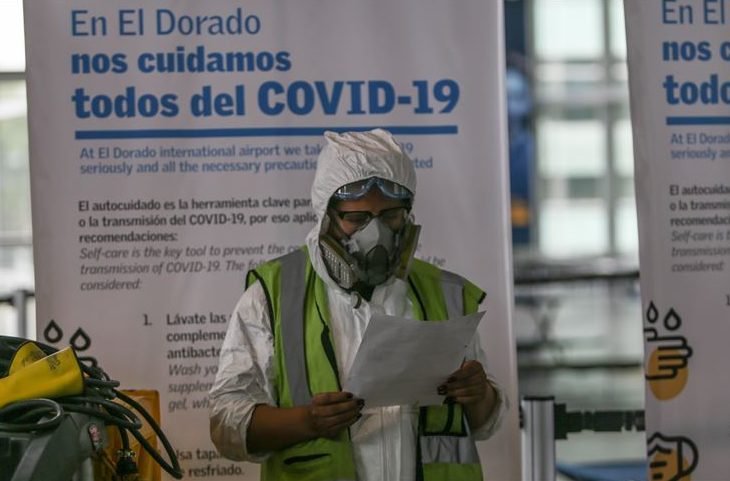

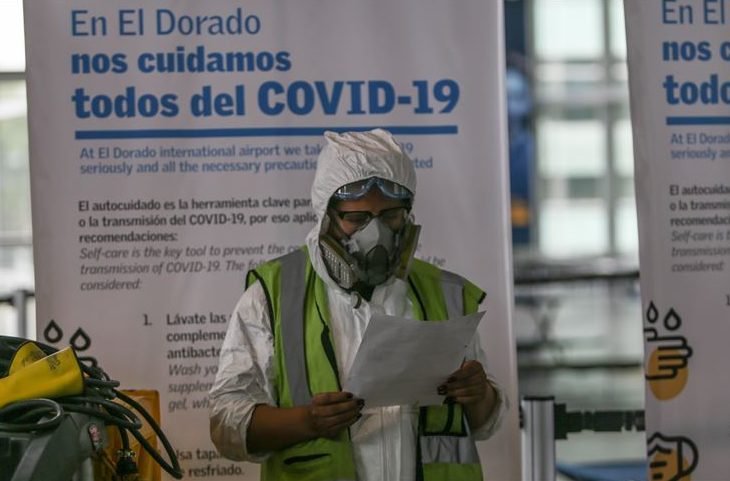

Apr 8, 2020 | Feature articles, News

A Feature Article by Rocio Quintero, Legal Adviser, ICJ Latin American Programme, based in Bogota.

Throughout several decades, a large number of Colombians have been victims of serious crimes related to the ongoing armed conflict. In particular, human rights defenders have been targets of serious human rights violations and abuses, such as killings, death threats, and harassments.

Just this year, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has received information of 56 possible cases of killings of human rights defenders. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 outbreak has not stopped the violence against human rights defenders.

In that regard, since the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the country on 6 March 2020, the Organization of American States (OAS) and International Amnesty has reported six killings. The perpetrators of those crimes have not been identified yet.

Human rights violations and abuses against local communities have not stopped either. Quite the opposite seems to be true.

In that regard, it is said that armed groups, including paramilitary groups and new groups made up of dissident FARC-EP members, are taking advantage of the outbreak to commit illegal actions with fewer constraints, mainly, in rural areas of the country.

Among these actions, it should be highlighted the enforced displacement of 250 people and the forced confinement of 770 families due to combats between a paramilitary group and a guerrilla group. Both actions took place in the pacific region of the country, an area where the conflict has intensified after the peace agreement. In addition, at least three ex-members of the FARC-EP have been murdered in March 2020.

Despite the seriousness of the situation described above, the Colombian government response to the COVID-19 crisis has focused on the creation and implementation of non-conflict-related measures.

In that regard, the Government has decreed various and vital regulations to mitigate the social and economic impact created by the virus. Among others, the president declared a state of emergency and a mandatory 19-day national quarantine that started on 25 March 2020.

The Government also established a program of economic and social aid for those who will be affected most by the quarantine.

None of the measures were designed bearing in mind the particular situation of human rights defenders. Consequently, their protection is not a central element of the Colombian pandemic policies.

Since the implementation of the peace agreement and victims’ rights are not top priorities of the current Government, the approach adopted is not entirely unexpected.

Although, to be fair, it should be recognized that the State programmes for the implementation of the peace agreement have continued operating during the pandemic.

It might be argued that the pandemic has the potential to affect predominantly human rights that have not been directly linked with the internal conflict.

Therefore, following this point of view, the prioritization of non-conflict-related measures is justified and required.

Although this position is based on a valid premise, which is that the COVID-19 pandemic creates several challenges that go beyond conflict-related human rights problems, it ignores a central element of Colombian reality: the existence of an ongoing armed conflict.

Currently, the conflict affects a considerable part of the Colombian population directly, including the majority of human rights defenders. In that regard, last year, it was reported illegal actions related to the internal armed conflict in at least 10 out of 32 departments of Colombia.

In this context, ignoring the importance of the conflict might lead to the implementation of ineffective pandemic measures. This is because, in conflict zones, the protection of human rights requires addressing the specific challenges that the pandemic has created in those territories.

For instance, the presence of illegal groups can prevent local communities from getting tested for COVID-19 and access to health services. Likewise, due to the quarantine, illegal groups might identify easier the location of human rights defenders and retaliate against them.

In relation to human rights defenders, it should also be highlighted the problems related to access to adequate protection measures. In that regard, Amnesty International has denounced that the protection measures for some human rights defenders have been reduced due to the pandemic.

In a similar way, a local NGO expressed concerns for the decision of the National Protection Unit to suspend indefinitely the sessions of the commission where protection measures are defined.

In light of the above, beyond political considerations and the general Government’s priorities, it is imperative that the Government adopts a more comprehensive approach to tackle the pandemic.

It should address the differential impact the pandemic might have on people who lead social and legal transformations in the conflict zones of the country.

In particular, it should implement or adapt protection measures to be effective during the COVID-19 crisis. Similarly, the right to an effective remedy and reparation should also be not only guaranteed, but realized, in compliance with international standards.

Additionally, it is also important that the national Government reinforce its efforts to obtain a humanitarian ceasefire by all illegal groups during the COVID-19 crisis.

A total ceasefire would contribute to (i) protecting the civilian population for violent actions, (ii) implementing the pandemic measures in conflict zones, and (iii) avoiding a proliferation of the virus in vulnerable communities.

This is a crucial measure that has already been requested by national civil organisations, the Head of the UN Verification Mission in Colombia, the OAS, and some parliamentarians.

As yet, only one illegal group has accepted a ceasefire: the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN), the largest active guerrilla in Colombia, who declared a unilateral ceasefire during April.

To conclude, acknowledging the importance of the conflict is essential to tackle the human rights implications of the COVID-19 crisis.

This is not only necessary to have comprehensive pandemic policies, but also to make sure that the problems and needs in the conflict zones are not neglected and aggravated during the pandemic.

On this point, as recently stated by UN Secretary-General, people who are most vulnerable during a conflict are also “most at risk of suffering “devastating losses” from the disease.”

Oct 31, 2019 | News

On 29-30 October the ICJ, in partnership with dhColombia and the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF), hosted a two-day training workshop in Bogotá on the legal framework around enforced disappearance and extrajudicial killings.

The training aimed to improve the understanding of victims and human rights lawyers of the domestic law on extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances in Colombia. It included an analysis of both the ordinary justice system, as well as transitional justice mechanisms. It also explored the role of the forensic sciences in tackling impunity for those crimes.

The ICJ in furtherance of its objective to promote accountability, justice and the rule of law in Colombia, has been continuously monitoring the investigation and prosecution of serious human rights violations and abuses, particularly extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. Perpetrators of such violations, which constitute crimes under international law, have enjoyed a high level of impunity. While there are numerous unresolved cases dating back to the 1970s, violations have continued even after a comprehensive peace agreement was signed in 2016 following decades of armed conflict.

In Colombia, achieving accountability for those crimes has proven difficult for several reasons, including the ineffective functioning of the justice system. Victims and their lawyers have faced serious obstacles in gaining access to effective remedies. In addition, the creation of new institutions by the Peace Agreement has changed some basic rules and procedures for the investigation and prosecution of those crimes. Consequently, the Colombian justice system is more complicated to understand not only for victims but for lawyers.

The training workshop was part of a broader regional project addressing justice for extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances in Colombia, Guatemala and Peru. Participants were victims and human rights lawyers from different regions of the country, especially those where that is less opportunity to access legal and forensic training. Considering that capacity building activities are essential to the effective achievement of accountability, it is expected that participants of the training will obtain valuable tools to demand justice and remedy and reparations for serious human rights violations.

Contacts:

Rocío Quintero M, Legal Adviser, Latin America. Email: rocio.quintero(a)icj.org

Carolina Villadiego, ICJ Legal and Policy Adviser, Latin America, and Regional Coordinator of the Project. Email: carolina.villadiego(a)icj.org

Sep 26, 2019 | Advocacy, Non-legal submissions

The ICJ today highlighted challenges and urged strengthening and support for the Special Jurisdiction for Peace in Colombia, at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva.

The statement was delivered during a general debate on technical assistance and capacity-building. It read as follows:

“The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) appreciates the contribution of UN technical assistance and capacity-building to implementation of the Peace Agreement in Colombia.

Full implementation of the Peace Agreement is important to the fulfilment of Colombia’s international human rights obligations, including rights of victims. In particular, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP by its Spanish acronym) is playing a key role in addressing accountability for gross human rights violations committed during the internal conflict in Colombia.

The JEP faces several challenges.[1] First, the JEP must do more to strengthen effective participation of victims in its procedures. Second, the Special Jurisdiction from the outset should ensure that the sanctions it imposes and reparation measures it orders are sufficient and appropriate to meet international standards. Third, national authorities, including the President and the Parliament, must respect the judicial independence of the Special Jurisdiction.

The ICJ also highlights the need for effective measures to address security threats faced by victims and witnesses appearing before the JEP.

We urge the UN, States and other stakeholders to provide technical assistance and capacity building towards strengthening guarantees for victim’s rights in the JEP’s procedures, and we urge the Human Rights Council to follow closely the work of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace to ensure it makes an effective contribution to fulfilling Colombia’s obligations under international law.”

[1] See also ICJ, Colombia: The Special Jurisdiction for Peace, Analysis One Year and a Half After its Entry into Operation (executive summary in English and full report in Spanish available at: https://www.icj.org/colombia-the-special-jurisdiction-for-peace-one-year-after-icj-analysis/).