Apr 28, 2020 | Advocacy, News, Open letters

The ICJ today called on the South African government to take measures to ensure access to justice and the full fulfillment of the economic, social and cultural rights of all in the country.

The South African authorities must also remove legal hurdles in accessing just compensation for rights violations occurring during nationwide lockdown, the ICJ said.

The call comes as South Africa enters its final week of a lockdown period, which initially began on 26 March 2020. Since the beginning of the lockdown period the ICJ has been working closely with a broad coalition of local civil society organizations and movements called the C19 People’s Coalition.

“The ICJ applauds South Africa on its announcement that it will commit 10% of its GDP to a social relief and economic support package addressing poverty and in inequality which has been exacerbated by COVID-19,” said Arnold Tsunga, ICJ Africa Director.

“However we note with concern the high levels of repression and human rights abuses committed by enforcement officers enforcing Lockdown Regulations and the inadequacy of social assistance measures to ensure an effective elimination of poverty in accordance with South Africa’s international and domestic human right obligations.”

- Repression and human rights abuses by enforcement officers during Lockdown

Both the Disaster Management Act and Lockdown Regulations enacted in terms of it create doubt about whether victims of violations of human rights in the enforcement of lockdown will be able to claim compensation for such violations.

The ICJ has therefore written to President Cyril Ramaphosa (photo) and Speaker of the National Assembly Thandi Modise calling on the authorities to make the necessary legal amendments required to ensure the full protection of the right to access to justice, which includes the right to effective remedies and reparation.

The ICJ calls on authorities to ensure the amendment of the National Disaster Act and Lockdown Regulations to ensure that victims of human rights abuses have full and effective access to the right to remedy and reparation including compensation.

- Inadequate Social Assistance provided

Despite the large stimulus package announced by President Ramaphosa on 21 April, the C19 People’s Coalition has correctly argued that the new COVID-19 social grant of R350 ($18.44 USD) per month for unemployed persons is less than a third of the R1227 ($64.65) that government itself estimates individuals require to be lifted out of poverty.

In addition, the increase of the Child Support Grant of R500 ($26.35) per month appears, contrary to what the President’s announcement suggested, to be allocated per caregiver not per child thus drastically reducing its potential impact.

The ICJ calls on authorities to ensure the full provision of a social safety net to all in South Africa by: 1) raising the levels of all non-contributory social assistance benefits to a level that ensures an adequate standard of living for recipients and their families; and 2) ensuring that those between the ages of 18 and 59 with little or no income have access to social assistance.

These two measures were among those specified in the Concluding Observations of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to South Africa.

South Africa declared a moratorium on all evictions during the lockdown period on 26 March after local organizations and the ICJ had called for such a move.

Later amendments to Lockdown Regulations made it a criminal offence for any person to evict any other person. Despite this, evictions continue in some places unabated as is illustrated by statements of Abahlali BaseMjondolo and Abahlali BaseMjondolo Women’s League late last week.

These evictions have sometimes been violent and accompanied by serious allegations of attempted murder of community members and human rights defenders.

The ICJ calls on authorities to ensure the immediate cessation of all evictions. The President of South Africa and the Parliament of South Africa must make sure that police officers, security and other companies and government officials participating in evictions are clearly, decisively and publicly held to account.

Those carrying out evictions should be prosecuted in accordance with Lockdown Regulations. The police and prosecuting authorities should also investigate and where sufficient evidence exists pursue prosecution of those found to have committed crimes of violence or similar offences against those who are subjected to or defend against such evictions.

“The continued violent attacks experienced by human rights defenders and those simply trying to retain their homes is unacceptable. The time has come for the President of South Africa and Parliament of South Africa to intervene directly to prevent any further such attacks generally, but in particular with regard to Abahlali BaseMjondolo settlements in KwaZulu-Natal,” added Arnold Tsunga, ICJ Africa Director.

Contact:

Tim Fish Hodgson, ICJ Legal Adviser, t: +2782871990 ; e: tim.hodgson(a)icj.org

Shaazia Ebrahim, ICJ Media Officer, t: +27716706719 ; e: shaazia.ebrahim(a)icj.org

Apr 7, 2020 | News

As South Africa enters into its second week of a 21-day lockdown, the ICJ calls on national, provincial and local government authorities to urgently implement measures to prevent sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) and protect women and children from it.

The country has been under lockdown since 26 March, with the population remaining at home, physically isolated in an attempt to ‘flatten the curve’ of transmission of the Covid-19 virus.

However, the lockdown means that some are trapped in their homes with their oppressors.

“A lockdown impacts women differently. For some women, being forced into lockdown with an already abusive partner heightens the risk of abuse and violence. It also means less support and fewer chances to seek help,” ICJ Senior Legal Adviser Emerlynne Gil said.

On 3 April, Police Minister Bheki Cele said that the South African Police Services had received 87,000 SGBV complaints violence during the first week of the national Covid lockdown.

Among the complainants was the wife of a police officer who reported that her husband had raped her. The officer has since been arrested.

The South African authorities have taken some steps to enhance women’s access to protection from SGBV during this lockdown, including by ensuring that women have access to courts for urgent civil matters, such as protection orders, as well as ensuring that there is an SMS line through which they can seek help.

Social services and shelters have also been made available. However, the authorities can and should go further in ensuring that these services are widely publicized, and that women have effective access them during the lockdown.

“Under international human rights law, States are legally obliged to take measures to prevent, address and eliminate SGBV,” ICJ Legal Associate Khanyo Farisè said.

“The South African authorities should do more, in particular, by raising awareness about GBV and providing comprehensive multi-sectoral responses to victims.”

Under international human rights law binding on South Africa, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, States are obligated to take all appropriate measures to eliminate violence against women of any kind occurring within the family, at the work place or in any other area of social life.

In a previous statement, the ICJ also called on States to ensure that measures to tackle Covid-19 are gender responsive.

The ICJ calls on South African authorities to:

- Widely publicize health and legal services, safe houses and social services and police services available to victims of SGBV, including the hotline 0800-428-428 or *120*786#

- Effectively respond to reported cases of SGBV and provide protection to victims through a multi-sectoral approach involving all relevant stakeholders.

- Investigate the causes of SGBV, including the surge of this scourge in the South African context during the COVID19 pandemic, and identify further measures to protect women against SGBV that are specifically required during pandemics.

- Implement “pop-up” counseling centres in mobile clinics or in pharmacies to support women who experience SGBV.

- Include the work of domestic violence professionals as an essential service and provide emergency resources for anti-domestic abuse organizations to help them respond to increased demand for services.

Contact

Khanyo Farisè, ICJ Legal Associate, e: nokukhanya.Farise(a)icj.org

Shaazia Ebrahim, ICJ Media Officer, e: shaazia.ebrahim(a)icj.org

Apr 6, 2020 | Advocacy, Analysis briefs, News

The briefing paper is published today in the context of significant uncertainty and distress experienced by migrant workers, refugees, asylum seekers, stateless people and other non-citizens in South Africa as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures that the authorities have taken with the stated aim of responding to it.

“All people residing in South Africa have the right to work and in earn a living in the country under international human rights law. The Government of South Africa should guard against laws, policies and public statements that discriminate against non-citizens especially during the public health emergency caused by COVID-19. Lockdown regulations and directions must be conceived and implemented in a way that fully enables all migrant workers performing essential services, including informal traders, waste reclaimers and shop owners to operate on an equal basis with South African citizens,” said Arnold Tsunga, the ICJ’s Africa Director.

The ICJ has previously condemned discriminatory statements made about non-citizen owners of “spaza shops” made by Minister Khumbudzo Ntshavheni in the context of COVID-19, and called on President Ramaphosa to publically repudiate these statements.

The briefing paper, which was produced in consultation with domestic, South African human rights organizations: the Socio-Economic Rights Institute and Lawyers for Human Rights, sets out the following clear principles of international human rights law regarding non-citizens’ right to work in South Africa:

- Everyone, regardless of citizenship status, has the right to work in South Africa under, among others, the International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights;

- This right to work, which is binding on South Africa, adds to the government’s constitutional obligations in terms of rights at work or the “right to fair labour practices”;

- The right to work protects both formal and informal workers, including non-citizens, in accordance with ILO Recommendation 204 and the General Comments of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights;

- The right to work applies to non-citizens irrespective of their documentary status in South Africa;

- No restrictions on the “core” obligations placed on states in terms of the right to work, as set out by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, are permissible;

- Restrictions or limitations on the right to work are permissible if they are set out in clearly in legislation, in pursuit of a legitimate objective, and are reasonable and proportionate taking into account the need to protect human dignity consistently with international human rights law and the Constitution;

- Any restrictions on non-citizens’ rights to work should be administrative (such as requiring permits or documentation), rather than substantive or categorical, otherwise they are likely to amount to prohibited forms of discrimination in terms of international and South African law; and

- Any administrative process designed by the State in this regard must be reasonable and proportionate and geared towards facilitating non-citizens ability to work in SA instead of limiting them.

Contact:

Tim Fish Hodgson, ICJ Legal Adviser, e: tim.hodgson(a)icj.org ; c: +2782871990

Shaazia Ebrahim, ICJ Media Officer, e: shaazia.ebrahim(a)icj.org ; c: +27716706719

Download

South Africa-Non Citizens Right to Work-Advocacy-Analysis Brief-2020-ENG (full paper in PDF)

Apr 2, 2020 | News, Op-eds

An opinion piece by Shaazia Ebrahim, ICJ Media Officer, and Tim Fish Hodgson, ICJ Legal Adviser on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, based in South Africa.

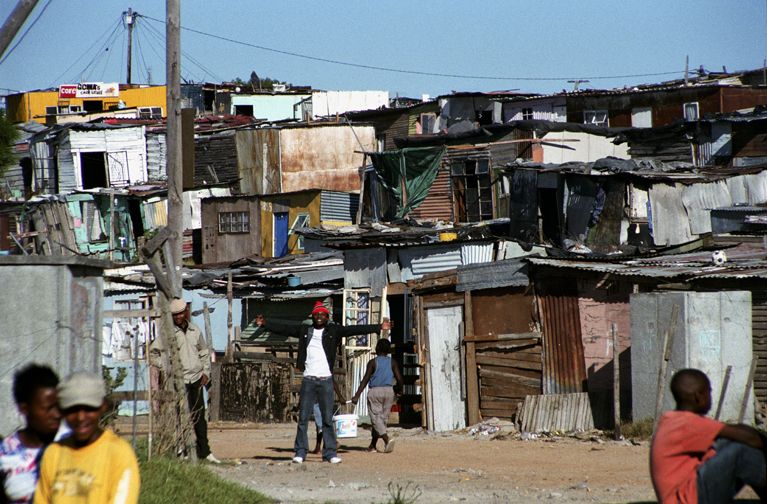

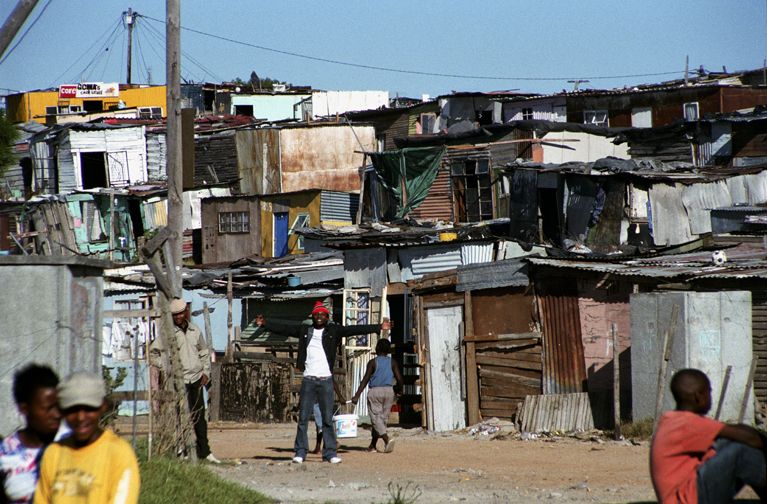

The inhumane conditions that most South African residents are subjected to in their daily lives will continue to deepen as the coronavirus spreads.

South Africans are encouraged to take precautionary measures to curb the spread of the pandemic by practising social distancing and intensifying hygiene control. The country will also be under a nationwide lockdown in order to “fundamentally disrupt the chain of transmission across society” from 26 March for 21 days.

The problem is that the recommended measures in South Africa, similarly to those of the World Health Organisation, assume that everyone lives in a house. A house which is at no risk of being destroyed by the state or private owners of the land upon which it is built: a house with access to water, sanitation and other basic services.

But the reality is that millions of South Africans do not live in a house, but in rudimentary structures in poor conditions. In a statement released this week, Abahlali baseMjondolo, a shack dwellers’ movement with members in various provinces across South Africa, articulated this.

Abahali’s frank assessment of the situation is that “it does not seem possible to prevent this virus from spreading when we still live in the mud like pigs”.

It is under the same conditions described by Abahlali baseMjondolo that many of the urban and rural poor in South Africa will be required to live under “lockdown”, commencing from midnight tonight.

Access to basic services: ‘if one person gets infected it’s disastrous’

Speaking before the release of the statement, Abahlali president S’bu Zikode expressed the distress that many around South Africa are currently experiencing. “Abahlali is very concerned about the outbreak of the coronavirus. The reason is, of course, that the conditions that we are subjected [give] us reason to be scared and worried,” he said.

“Social distancing” is difficult for many in South Africa. Government regulations say no more than 100 people should be “gathering” and people are more generally encouraged to keep a distance from one another. In Abahlali’s settlements, Zikode explains, there are thousands living close together under strenuous conditions.

“That on its own is automatically disrespecting the call from the president”, he said.

Abahlali, alongside various other South African movements and organisations, have for years been calling for the state to improve their living conditions and provide them with access to water, sanitation and other basic services.

In 2019 the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights noted its concern about “the large number of people living in inadequate housing, including those in informal settlements, without access to basic services; the growing number of informal settlements in urban areas due to rapid urbanisation”.

These calls have not received a sufficiently serious response from the government. Litigation to ensure access to basic services remains commonplace.

In this context, while hygiene has rightly been touted as one of the most important preventatives from spreading Covid-19, it is difficult to imagine how the majority living in South Africa will be able to ensure even basic measures such as handwashing.

Abahlali notes that in many informal settlements “hundreds of people [are] sharing one tap”. In this context, it is easy to see why leaders of Abahlali think that as it stands, preventing the spread of coronavirus is very important, but all but impossible.

“As leaders of Abahlali, we see it as once one person gets infected in the settlements, suddenly the entire settlement will be disastrous,” Zikode said.

A moratorium on evictions: halting evictions ‘will save lives’

Making matters worse, members of Abahlali, like many others in their country, lack security of tenure. As trying as their current circumstances may be, Abahlali warns of the potentially devastating effects of evictions during the pandemic. Another common way to induce evictions is to disconnect existing access to water, electricity and sanitation.

This is why Abahlali demands that “all evictions must be stopped with immediate effect” and that “all disconnections from self-organised access to water, electricity and sanitation must be stopped with immediate effect”. Indeed, it is difficult to see how any eviction during the pandemic could be “just and equitable” in “all relevant circumstances” as is required by South African law.

The call for a “moratorium” on evictions has also been made by a large group of social movements and civil society organisations in South Africa in a letter to the president. It has also received clear support from the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, who has called for a “global ban” on evictions worldwide:

“The logical extension of a logical stay-at-home policy is a global ban on evictions. There must be no evictions of anyone, anywhere, for any reason. Simply put: a global ban on evictions will save lives”, she said. The International Commission of Jurists has echoed these calls and the calls for connection of emergency water for all before the nationwide lockdown commences.

Coronavirus, the right to housing and access to land

In February, in giving input to the parliamentary committee contemplating the need to amend the Constitution to expedite land reform, Abahali argued that land is not a commodity and that the Constitution should include a “right to land” which it does not at present.

“Land should be shared and should be viewed as a public good”, Zikode explains.

Abahlali argues that the absence of a right to land in the Constitution undermines the constitutional right to housing: without land there can be no housing. Consistently with this logic, as early as 2000, South Africa’s Constitutional Court held emphatically that:

“For a person to have access to adequate housing all of these conditions need to be met: there must be land, there must be services, there must be a dwelling.”

The current crisis brought on by the coronavirus adds weight to Abahlali’s position on land. Access to land and security of tenure are necessary for access to adequate housing. If people have access to land and secure tenure, evictions are not a constant threat to their well-being.

Without access to housing and basic services, public health is severely compromised on a daily basis. Public health emergencies such as the coronavirus pandemic put even further pressure on an already compromised living environment. They therefore highlight that for many people, the right to adequate housing can only be discharged with full access to land.

The obligations of the South African government

The government of South Africa has rightly been praised for its proactive response to the coronavirus pandemic. The regulations passed in terms of the Disaster Management Act require that measures taken to combat coronavirus are implemented “as far as possible, without affecting service delivery in relation to the realisation of the rights” including the rights to housing and basic services, healthcare, social security and education.

The president’s announcement of a countrywide lockdown included a commitment that “temporary shelters that meet the necessary hygiene standards will be identified for homeless people”. Nevertheless, Abahlali’s members, who are not strictly homeless, might take cold comfort.

Disappointingly, the president failed to announce a moratorium on evictions or make any mention of evictions at all. This not only leaves many more people under the threat of being rendered homeless but may also lead to devastating displacement that will make the further spread of coronavirus possible.

The president did indicate that “emergency water supplies” are “being provided to informal settlements and rural areas”.

However, he did not make mention of whether expedited or emergency provision of other basic services such as sanitation, electricity and waste removal services where they are not currently available would occur. Urgent calls for emergency water connection coming out of Khayelitsha suggest that in many places in major informal settlements such emergency connections have not occurred.

The government of South Africa should be applauded for taking emergency measures. However, in so doing, it is implicitly acknowledging that many — if not most — South African residents have been living on a daily basis in conditions that are insufficient for them to live healthy, dignified lives.

This highlights the government’s existing and continuous failures to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights to access to housing and basic services.

The coronavirus, therefore, stands a stark reminder to all in South Africa of the dire impacts of social inequality in the country and the pressing need for government to pursue the realisation of all its obligations in terms of social and economic rights protected in the South African Constitution and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It also lends strong credence to the need for serious consideration of Abahlali’s claim for the need of a constitutionally protected right to land.

As Zikode concludes:

“Abahlali has always been about the land, decent housing, and dignity. Without land, housing is impossible. Without land, dignity is compromised. Land is close to the heart of many mainly black South Africans and it’s very close to the heart of Abahlali.”

Originally published in Daily Maverick

Mar 25, 2020 | News

The ICJ today called on the South African government to take urgent and immediate measures to ensure the full protection human rights, including economic, social and cultural rights, in the context of the COVID 19 epidemic.

The call comes as South Africa’s 21-day nationwide lockdown is poised to commence tomorrow, 26 March 2020. As it stands the human rights of the majority of South African residents are under serious threat.

“The ICJ is calling on the South African government to take effective measures ensure that addressing one human rights crisis does need lead to new human rights pressures” said Arnold Tsunga, Director of or the ICJ Africa Programme.

“We therefore call on the authorities to take three urgent steps: 1) Declare a moratorium on all evictions; 2) Ensure emergency provision of water to all; and 3) publically repudiate xenophobic statements made by Minister Khumbudzo Ntshavheni and affirm non-citizens rights to work”.

- Declaration of a moratorium on all evictions:

In the context of COVID-19, evictions are particularly dangerous and life-threatening. Evictions risk the further spread of COVID-19 and make it impossible to stay at home as the World Health Organization has advised.

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, has called for a global ban on evictions worldwide, stressing that: “The logical extension of a logical stay at home policy is a global ban on evictions. There must be no evictions of anyone, anywhere, for any reason. Simply put: a global ban on evictions will save lives”. In South Africa, local social movements and human rights organizations have called for a “moratorium” on evictions, as has Abahlali BaseMjondolo a movement of tens of thousands of “shack dwellers” across the country.

The ICJ calls on President Ramaphosa to declare a moratorium on evictions immediately before the commencement of the nationwide lockdown. South Africa must do so to meet its international legal obligations to protect the rights to housing and health.

- Provision of emergency access to water before the lockdown commences:

Many people in South Africa live in informal settlements and rural settings in which access to water, sanitation and basic services are inadequate or inconsistent. The simple instruction of washing one’s hands to prevent the spread of the virus is extremely difficult, if not impossible, for many.

The President announced on 23 March that “emergency water supplies” would be provided in “informal settlements and rural areas”. However, reports from around the country suggest that with lockdown beginning tomorrow many major informal settlements, including Khayelitsha in Cape Town, still do not have sufficient access to such emergency water.

The ICJ calls on President Ramaphosa to ensure that provision is made for all South Africans to have access to basic services, including water, before the commencement of national lockdown. South Africa must do so to meet its international legal obligations to protect the right to water.

- Protecting the right to work of “everyone” including non-citizens:

On 24 March 2020 speaking on national television, Minister of Small Business and Development in South Africa Khumbudzo Ntshavheni said that only spaza shops “owned by South Africans and managed and run by South Africans” will be allowed to continue operating during nationwide-lockdown, ostensibly to ensure the quality of goods and food.

This statement is discriminatory and in violation of South Africa’s commitments in terms of its own Constitution and international human rights law, to ensure non-discrimination and equal protection of the law. It risks a resurgence of existing xenophobic sentiment at a time of crisis which South Africa can ill afford and threatens the livelihood of foreign nationals.

The ICJ calls on President Ramaphosa to withdraw the statement immediately and reaffirm the internationally recognized right to equality of non-citizens including their right to work.

Contact:

Tim Fish Hodgson, ICJ Legal Adviser, e: tim.hodgson(a)icj.org ; c: +2782871990

Shaazia Ebrahim, ICJ Media Officer, e: shaazia.ebrahim(a)icj.org ; c: +27716706719

Background:

The global Covid-19 pandemic has led South African president Cyril Ramaphosa to announce a 21-day nationwide lockdown which will be effective on 26 March at midnight. This follows on from South Africa’s declaration of a “national disaster” on 15 March and the publication of disaster regulations governing the disaster response.

Global consensus on best practice to combat COVID-19, as recommended by the World Health Organization, is for people to stay at home, maintain social distance and intensify hygiene measures including through frequent washing of hands. However, South Africa has well-documented and extremely high levels of poverty and inequality. A number of problems in complying with global best practice in response to COVID-19.

The disaster regulations require that measures taken to combat COVID-19 are implemented “as far as possible, without affecting service delivery in relation to the realisation of the rights” including the rights to housing and basic services, healthcare, social security and education.