Jul 24, 2018 | Advocacy, Analysis briefs, News

In a briefing paper published today, the ICJ called on the parties to the conflict in Yemen to take immediate and effective measures to ensure the protection of the civilian population, including against human rights abuses and international humanitarian law violations.

Serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in Yemen include direct and indiscriminate attacks against civilians and the impediment of access to humanitarian relief of the civilian population.

Gross human rights violations and abuses include widespread instances of arbitrary arrest and detention, torture and ill-treatment, and enforced disappearances.

The ICJ has called for persons responsible for such violations to be held to account.

“All parties to the conflict in Yemen have acted in blatant disregard of the most basic rules of international humanitarian law and human rights law,” said Said Benarbia, ICJ MENA Director.

“The top priority is to end these violations and in particular to protect the civilian population,” he added.

In its briefing paper, the ICJ analyses international law violations committed in the conduct of hostilities and against persons deprived of their liberty.

The Saudi Arabia-led coalition and the Houthis are allegedly responsible for direct, indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks against civilians and civilian objects, including local markets, food storage sites, water installations and medical facilities.

The United Arab Emirates, the internationally recognized government of Yemen and the Houthis have allegedly engaged in arbitrary arrest and detention, torture and ill-treatment, and enforced disappearances.

The ICJ briefing paper also examines the potential legal implications of the blockade imposed by the Saudi Arabia-led coalition on Yemen and the sieges laid by the Houthis against several towns and localities, which impede the civilian population to access humanitarian relief.

The ICJ briefing paper further assesses the potential responsibility of third States for transferring arms to the parties to the conflict.

Under numerous instruments, including the Arms Trade Treaty, States are prohibited from selling arms to the parties to an armed conflict whenever a risk exists that the end-user could commit international law violations.

Arms transfers may even engage the exporting States’ international responsibility for aiding or assisting in the commission of such violations.

“Victims must have access to effective legal remedies and be provided with adequate reparation,” Benarbia said.

“The international community must state loud and clear that impunity is not an option. The Security Council should refer the situation in Yemen to the International Criminal Court and third States should consider, where feasible, the exercise of universal jurisdiction to prosecute relevant crimes under international law,” he added.

Contact

Vito Todeschini, Associate Legal Adviser, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, t: +216-71-962-287; e: vito.todeschini(a)icj.org

Said Benarbia, Director of the ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, t: +41-22-979-3817; e: said.benarbia(a)icj.org

Yemen-War briefing-News-web story-2018-ENG (full story with background information, English, PDF)

Yemen-War impact on populations-Advocacy-Analysis Brief-2018-ENG (Analysis Brief in English, PDF)

Yemen-War briefing-News-web story-2018-ARA (full story with background information, Arabic, PDF)

Yemen-War impact on populations-Advocacy-Analysis Brief-2018-ARA (Analysis Brief in Arabic, PDF)

Jul 24, 2018 | News

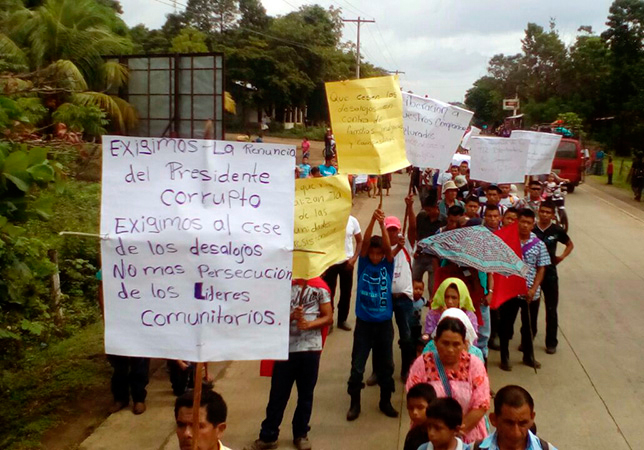

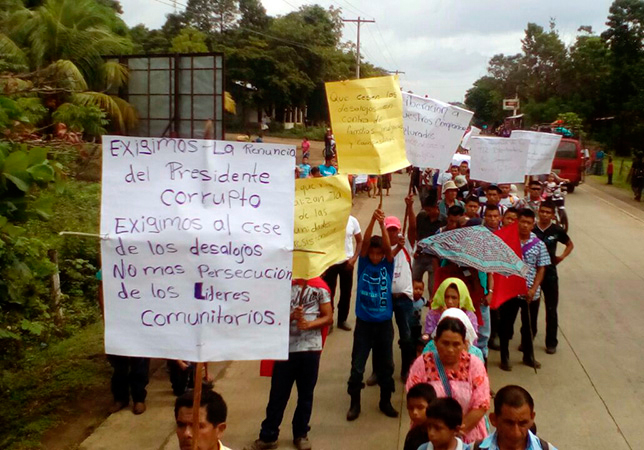

For many years, human rights defenders in Izabal have been the victims of persecution because of their opposition to the Phoenix nickel mining project.

This project has been operated by the Guatemalan Nickel Company (CGN), formally owned by Hudbay and now owned by the Solway Group.

“The ICJ expresses its deep concern about the persecution of human rights defenders opposing to nickel mining operations that are causing serious environmental damage and irreparable harm to the Lake of Izabal.

The local communities’ peaceful resistance contrasts with the violent repression that they face,” Ramon Cadena, Director of the Central American Office of the ICJ, said today.

Ramon Cadena added: “the Guatemalan government must urgently put an end to the criminalization and persecution of community leaders, journalists and all human rights defenders in the Department of Izabal.

Internal disciplinary measures should be taken against judges who through their acts contribute to the persecution of persons exercising their legitimate rights and freedoms.

The State should provide reparations for the harm and prejudice caused to human rights defenders by the public authorities. Furthermore, the International Commission against Corruption and Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) should fully investigate these acts.“

Eduardo Bin Poou, Vice-President of the Izabal Fishers’ Association was recently detained and falsely accused without any evidence that he had committed any crime.

Last year, on 27 May 2017, Carlos Maas Coc, a leader of the Fishers’ Association was assassinated, and another fisherman, Alfredo Maquín Cocul, was wounded and these crimes remain in impunity today.

From 18-20 July, 2018, the ICJ carried out a visit to the Department of Izabal. On 19 July, the ICJ observed the hearing when the case against Jerson Xitumul, a community journalist, was dismissed for lack of evidence of any wrongdoing, at the Court for Criminal, Narcotics and Environmental Offences in Puerto Barrios.

The ICJ then held a meeting with the Izabal Fishers’ Association and on 20 July, the ICJ interviewed the Vice President of the same Association, Eduardo Bin Poou, arbitrarily detained in the Puerto Barrios prison.

The ICJ is deeply concerned by the role that judges in the Department of Izabal have played in the criminalization of human rights defenders.

Judge Edgar Aníbal Arteaga López has often abused his office by imposing exemplary punishments against human rights defenders.

This judge has handed down arbitrary sentences against journalists, fishermen, community leaders, land rights’ defenders and all those opposed to the nickel operations or who defend community rights in the Department.

For example, because of the arbitrary actions of Judge Arteaga, the community leader, Abelardo Chub Caal, remains in detention although there is no evidence that he has committed any crime.

There are other cases including that of Maria Magdalena Cuc Choc, from the Chabilchoch community, who was detained on 17 January 2018 in Puerto Barrios.

The single Judge for Criminal Proceedings, Narcotics and Environmental Offences in Puerto Barrios, Ana Leticia Peña Ayala, despite the evidence, absolved the retired Colonel Mynor Ronaldo Padilla González (former chief of security for the CGN nickel company) of all charges and ordered his immediate liberty.

During the court case, the Judge Peña Ayala prohibited the public and journalists from entering the court room for so-called “security reasons”, so that most of the proceedings were carried out behind closed doors. With this ruling, the assassination of Adolfo Ich remains in impunity and those responsible have not been punished.

In this same case, Germán Chub was left quadriplegic and the circumstances of the attack against him have never been resolved.

In the hearing on 19 July in the case of Jerson Xitumul, without any justification, Judge Arteaga also prohibited the presence of journalists and international and national observers in the court room.

Both judges flagrantly violated the principle of public hearings established in the Guatemalan Penal Code. A formal complaint was submitted to the Auxiliary of the Human Rights Attorney of the Department of Izabal concerning the actions of Judge Arteaga on 19 July.

The ICJ has stated on a number of occasions that the Guatemalan authorities have persecuted human rights defenders by charging them with crimes of land appropriation or aggravated land appropriation.

In this way, the Guatemalan authorities seek to criminalize the legitimate right to resist, enshrined in article 45 of the Guatemalan Constitution, accusing environmental human rights defenders and others of crimes such as incitement to crime, illegal detention, threats, damages, illicit meetings and marches and other acts. In practice, the State is penalizing the legitimate exercise of the rights of expression and association.

Jul 19, 2018 | News

His Majesty King Mswati III of the Kingdom of Eswatini (formerly known as the Kingdom of Swaziland) yesterday gave his royal assent to the Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Act, a milestone in the fight against sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in the country.

In its May 2018 report on key challenges to achieving justice for human rights violations in Swaziland, the ICJ identified the widespread occurrence of SGBV, with discriminatory practices based on customary laws and traditional beliefs undermining equality between men and women and the access by victims of such violence to effective remedies and reparation, as well as the holding to account of perpetrators of such violence.

Eswatini’sNational Strategy to End Violence in Swaziland 2017-2022, produced by the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister in collaboration with the UN Population Fund, itself pointed to an alarming rate of increasing violence in all its forms, noting that its most common form was gender-based violence, disproportionately affecting women and girls.

The new law follows a protracted legislative process, first initiated in 2009; then resumed in 2015. It has also been accompanied by increasing attention and concern by international human rights mechanisms, including the UN Human Rights Committee and the Committee on Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

Building on ICJ initiatives to bring together international, regional and local SGBV experts in 2015, and on sustainable development goals on access to justice and gender equality in 2017, the ICJ with local partners convened a workshop on combatting SGBV in Swaziland in February 2018. In consultations during and around this most recent workshop, interlocutors signaled fears that the Senate of Swaziland was equivocating on passage of the 2015 Bill. Responding to local partners’ requests, the ICJ made a submission to the Senate in March 2018, bringing to its attention to the global and regional obligations of the Kingdom to enact the legislation, as well as the Government’s own commitments to do so. The Senate soon after voted to adopt the legislation.

The new law for the first time criminalizes marital rape and other domestic violence offences; makes provision for Specialised Domestic Violence Courts; creates mechanisms and avenues for reporting of offences; and requires medical examination and treatment of victims. These are issues that had not been previously provided for.

Enactment of the law is significant, incorporating into domestic law a very large part of Eswatini’s international human rights obligations, including those arising from the Africa region, to criminalize and sanction the perpetrators of SGBV. It also discharges commitments made by His Majesty’s Government during the 2016 Universal Periodic Review.

Just as important will be the effective implementation of the new law to combat SGBV by bringing perpetrators to account and providing victims with access to justice.

With a view to enhancing the prospects of an effective and comprehensive approach to that end, the ICJ’s Commissioner, and Principal Judge of the High Court, Justice Qinsile Mabuza, will next week be coordinating a meeting of governmental justice sector stakeholders involved in combatting SGBV in the country. This first coordinated meeting of governmental actors will focus on issues of investigation, prosecution and sanctioning of sexual and gender-based violence crimes, including the role of social and medical services.

The ICJ is also commissioning a report on the access of victims of SGBV to effective remedies and reparation. Focused on case studies, the report will include attention to lack of justice through acquittals that have been prompted by inadequate laws or procedures and/or through lack of prompt or sufficient forensic or medical evidence. This report will feed into discussions at a second meeting of governmental justice sector stakeholders, intended for 2019.

Jul 18, 2018 | News, Publications, Reports

The ICJ welcomed today the lapse of Turkey’s nearly two-year state of emergency, which is expected to be effective as of midnight, but said that the authorities needed now to take a range of measures to repair the rupture to the rule of law in the country.

The ICJ’s comments came as it released its report Justice Suspended – Access to Justice and State of Emergency in Turkey, outlining how measures undertaken pursuant to a state of emergency, including the mass dismissal of judges and arbitrary arrests and prosecutions of lawyers and human rights defenders had eroded the justice institutions and mechanisms in the country.

The report recommends a number of measures including the repeal of measures enacted under the state of emergency, the restoral of the independence of the judiciary and the reform of the country’s anti-terrorism legislation.

“With the end of the state of emergency we call for the immediate withdrawal of the notifications of derogations to the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” said Massimo Frigo, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser for the Europe and Central Asia Programme.

“We remain concerned that many of the emergency measures have been given permanent effect in Turkish law and will have pernicious and lasting consequences for the enjoyment of human rights and for the rule of law in Turkey,” he added.

These measures include the dismissals of hundred of thousands of people from their job, including judges and prosecutors.

Constitutional amendments, introduced during the state of emergency, permanently enshrine executive and legislative control of the governing institutions of the judiciary, contrary to international standards on judicial independence, the ICJ says.

Many of those charged with vaguely-defined offences under the state of emergency face trial before courts that are not independent and cannot guarantee the right to a fair trial, the Geneva-based organization adds.

Crucially, most of the people affected by emergency measures, including summary dismissals, have not yet had the opportunity to obtain a remedy before an effective and independent court or tribunal.

The ICJ report illustrates how the mechanisms which should address and remedy human rights violations in Turkey lack effectiveness and independence and that these deficiencies extend both to the courts and the state of emergency complaints commission.

It further finds that the ordinary functions of lawyers and activities civil society, key actors in ensuring access to justice, have been considerably curtailed.

“The Turkish Government says that they want their actions to respect the rule of law. Effective and independent remedies and reparations for human rights violations must be available to all if this principle is to have any reality in practice,” said Massimo Frigo.

Contact

Massimo Frigo, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser for the Europe and Central Asia Programme, t: +41 22 979 3805, e: massimo.frigo@icj.org

Download

Full ICJ report in PDF in English: Turkey-Access to justice-Publications-Reports-2018-ENG

Full ICJ report in PDF in Turkish: Turkey-Access to justice-Publications-Reports-2018-TUR

Jul 15, 2018 | News

On 14 July 2018, the ICJ co-organized a discussion on extrajudicial killings in Thailand, focusing on the cases of Chaiyaphum Pasae and Abe Saemu.

The discussion was held at the Student Christian Centre in Bangkok.

Chaiyaphum Pasae, a Lahu youth activist, was killed by a military officer in the Chiang Dao district of Thailand’s northern Chiang Mai province in March 2017. The killing took place during an attempt to arrest him as an alleged drug suspect. Officials claimed Chaiyaphum Pasae had resisted arrest and was subsequently shot in “an act of self-defence”.

Abe Saemu, from the Lisu hill tribe, was killed by a military officer in February 2017 in the Chiang Dao district of Chiang Mai province in an attempt to arrest him on allegations of drug coffences. Officials claimed Abe Saemu had resisted arrest and was killed in “self-defence”.

During the discussion, ICJ’s National Legal Adviser Sanhawan Srisod addressed the audience to set out the international law and standards that apply to investigating potentially unlawful deaths, including the rights of victims and family members, referring to the standards set out in the revised Minnesota Protocol on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Death (2016), which was launched in Thailand on 25 May 2017.

Participants in the event included members of the families of Chaiyaphum Pasae and Abe Saemu, the lawyers in both of their cases, interested members of the public, media representatives, students and academics.

The discussion opened with an art exhibition and Lahu dance show by the Save Lahu group. Human Rights Commissioner Angkhana Neelapaijit then made a presentation on challenges in seeking accountability for extrajudicial killings in Thailand.

A panel discussion on the latest updates in the cases of Chaiyaphum Pasae and Abe Saemu followed, moderated by Pranom Somwong from Protection International.

The panel included relatives of Chaiyaphum Pasae and Abe Saemu; Ratsada Manuratsada, a lawyer representing the families in both cases and Krissada Ngamsiljamras, a representative from the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand.

A second panel considered challenges on the administration of criminal justice in the context of unlawful deaths.

Moderated by Pratubjit Neelapaijit of UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the panel included Malee Sittikreangkrai (Chiang Mai University); Sumitchai Hattasan (Human Rights Lawyers’ Association); Namtae Meeboonsalang (Provincial Chief Public Prosecutor, Office of the Attorney-General); Kritin Meewutsom (Forensic doctor, Ranong Hospital); and Sanhawan Srisod (ICJ).

The event was conducted in collaboration with Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF); Protection International (PI); UN OHCHR; Human Rights Lawyers’ Association (HRLA); Thai Volunteer Services (TVS); Dinsorsee Creative Group; Center for Ethnic Studies and Development, Chiang Mai University (CESD); Legal Research and Development Center, Chiang Mai University (LRDC) and Network of Indigenous Peoples in Thailand (NIPT).

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, Senior Legal Adviser, ICJ Asia Pacific Regional Office, kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org