Mar 15, 2019

Today the ICJ issued a Legal Brief note in order to help in understanding the offence of Subverting a Constitutional Government under Zimbabwe law.

Following protests that occurred in most major cities and towns in Zimbabwe in January 2019, a number of activists, human rights defenders, civil society leaders and opposition leaders have been arrested and charged with ‘subverting constitutional government’ as provided for under section 22 of the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act [Chapter 9:23] (hereinafter referred to as the Criminal Code).

This legal briefing note seeks to provide an explanation of the elements of the crime and how it has been construed by Zimbabwean courts, and whether and to what the resort to section 22 has accorded with international law and standards, including African regional standards.

Under Zimbabwe’s existing laws, a person may be charged with an offence known as ‘subverting constitutional government’.

This is a crime akin to but less serious than treason. It is nonetheless an offence which attracts a sentence of up to 20 years in prison.

Various protesters have been arrested on the allegations that their public statements amounted to inciting the commission of this crime.

Following the January 2019 protests, more than 5 protesters and MDC opposition members have been charged with this crime.

Despite the high number of arrests based on this charge in the past few years, there have been no convictions.

Where the basis of the charge are public statements made, the question of what exceeds legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of expression arises.

As such, there is need to interrogate where the line is drawn between legitimate and illegitimate exercise of the right to freedom of expression.

International human rights law, pursuant both universal and African regional standards, protects for the rights of persons to freedom of opinion and expression (Article 9 ACHPR; article 19 ICCPR), freedom of assembly (article 11 ACHPR;21 ICCPR) article, freedom of association (article 10 ACHPR; article 22 ICCPR), and the right to political participation (article 25 ICCPR).

These provisions in these international instruments impose an obligation on all state parties to respect the rights of persons under their jurisdiction.

Zimbabwe as a member state is bound by these provisions and similar provision under sections 58 (freedom of assembly and association), section 59 (freedom to demonstrate and petition), section 60 (freedom of conscience) and section 61 (freedom of expression).

These rights and fundamental freedoms, when exercised by human rights defenders, have been accorded heightened protection in international standards in particular through the UN Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (Declaration on Human Rights Defenders), adopted in 1999 by consensus of the General Assembly

While these freedoms are not absolute, under international law, any restrictions must be (i) legitimate, provided by law which is clear and accessible to everyone and formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate his or her conduct; (ii) proven strictly necessary to protect the rights or reputation of others, national security or public order, public health or morals and (iii) proven to be the least restrictive and proportionate means to achieve the purported aim.

Contact

Elizabeth Mangenje, e: elizabeth.mangenje@icj.org

Brian Penduka, e: brian.penduka@icj.org

Arnold Tsunga, e: arnold.tsunga@icj.org

Zimbabwe-Subverting Constitutional Gvt-Advocacy-Analysis Brief-2019-ENG (full legal brief in PDF)

Mar 5, 2019 | News

On 4 March 2019, Malaysia acceded to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), making it the 124th State Party to the ICC.

“The decision by Malaysia’s government to become party to the Rome statute should be commended as a positive sign of its commitment to the rule of law and acceptance to work with the global community to end impunity and ensure accountability for some of the gravest crimes under international law,” said Frederick Rawski, the ICJ’s Asia-Pacific Director.

The ICJ considers the establishment of the ICC as a watershed achievement in the development of international law and the will and capacity of States to act in concert to address atrocities around the world that carry devastating consequences for the victims.

The aim to end impunity on a global scale requires that the Rome Statute be ratified universally.

The ICC was established in 2002 as a permanent international criminal court to investigate and, where warranted, put on trial individuals charged with the some of the most serious crimes of international concern, particularly the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression.

The Rome Statute operates on the principle of complementarity, meaning that the ICC can only become engaged when the responsible States are unable or unwilling to investigate and prosecute allegations at the national level.

“Malaysia’s accession serves as an example for the entire Asian region, which has been significantly underrepresented at the ICC,” said Rawski.

“It sends a timely message of support for international accountability, at a moment when the actions of two of Malaysia’s neighboring countries – Myanmar and the Philippines – are the focus of preliminary investigations by the ICC, and after Philippines announced its intent to withdraw from the Statute last year,” he added.

In March 2018, the ICC was formally notified by Philippines of its intention to withdraw from the Rome Statute after the court initiated a preliminary examination into allegations of crimes committed in the context of the Philippines’ government’s “war on drugs” campaign since July 2016. The ICJ condemned this move as a blow to international justice.

In September 2018, the ICC launched a preliminary examination into allegations of forced deportations of Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar into Bangladesh, on the basis that the court had jurisdiction because Bangladesh is a State Party and the deportations occurred in part on Bangladeshi territory. The ICJ submitted an amicus curiae in support of such jurisdiction.

Contact

Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia and Pacific Regional Director, e: frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

See also

Philippines: the Government should reconsider withdrawal from ICC

ICJ submits Amicus Curiae Brief to International Criminal Court

Mar 1, 2019 | Events, Multimedia items, News, Video clips

This event took place today at the Palais des Nations, United Nations, in Geneva. Watch it on video.

The situation of the rule of law in Turkey and of human rights defenders who promote it continues to be of serious concern.

Following the attempted coup of 15 July 2016, the two-year state of emergency and security legislation enacted thereafter, human rights defenders face harassment and are subject to pressure by authorities, including by unfounded criminal charges of terrorist offenses. Lack of accountability for gross violations of the rights of human rights defenders is also a particular problem.

The panel discussion at this side event will also focus on the situation of human rights defenders for the rule of law in Turkey and the lack of accountability for human rights violations against them, including for the killing of the head of the Bar Association of Diyarbakir three years ago.

The event is organized by the ICJ jointly with the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute.

Speakers:

– Michel Forst, UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders

– Feray Salman, Coordinator of the Human Rights Joint Platform (IHOP)

– Kerem Altiparmak, ICJ Legal Consultant

– Jurate Guzeviciute, International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute

Chair:

Saman Zia-Zarifi, ICJ Secretary General

Event Flyer:

Turkey- HRD side event HRC40-News-Events-2019-ENG

https://www.facebook.com/ridhglobal/videos/795507517477571/

Feb 19, 2019 | News

The ICJ today called for the Italian Senate to allow for the investigation of the Minister of Interior and Vice-President of the Council of Ministers, Matteo Salvini, for his role in the alleged arbitrary deprivation of liberty of some 177 persons, including potential refugees, held for five days on the “U-Diciotti” boat last summer.

The ICJ said that the Italian Senate’s Commission on Elections and Immunities should recommend the authorization of the criminal investigation to the full Senate, where Matteo Salvini also sits as a Senator.

“The decision on investigation of gross human rights violations such as mass and arbitrary deprivation of liberty should not be subject to political scrutiny but be left to the assessment of the judiciary,” said Massimo Frigo, Senior Legal Adviser for the ICJ Europe Programme.

The indictment for “kidnapping” against Minister Salvini has already been approved at the judicial stage by the Tribunal of Ministers of Catania, which affirmed that Minister Salvini is alleged to have abused his administrative power in this matter for the political goal of negotiating resettlements with other European countries.

“No human being should effectively be made hostage for the purpose of political negotiations,” said Massimo Frigo.

“It does not matter which country may have been primarily responsible for the rescue at sea. No authority may arbitrarily restrict of the right to liberty of 177 human beings,” he added.

The ICJ considers that it is highly problematic for the principle of the rule of law that the decision on prosecution for a crime underlying a gross violation of human rights, such as kidnapping, be entrusted to a political body.

This decision should be left to the judiciary based on legal and not political grounds.

Under international human rights law, including the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, States have an obligation to investigate, prosecute, try and, if found guilty, convict persons responsible of gross violations of human rights, among which counts the arbitrary deprivation of liberty.

This applies to all State officials, irrespective of their position of authority.

Contact

Massimo Frigo, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser, t: +41 22 979 38 05 ; e: massimo.frigo(a)icj.org

Background

The Italian “U. Diciotti” boat was at the centre of a political scandal last August when the Minister of Interior Matteo Salvini refused disembarkation of 177 people for several days in order to negotiate their resettlement with other European countries.

While the boat entered Italian waters on 20 August, they were eventually disembarked in the night between Saturday 25 and Sunday 26 August after some countries and the catholic church made some nominal declaration of resettlement or reception.

Minister Salvini was later accused of “kidnapping” for having arbitrarily deprived of their liberty the 177 persons on board the “U.Diciotti”. While the prosecutor in the case asked for the dismissal of the charges, the Tribunal of Ministers, composed of ordinary judges, that is responsible for the legal assessment of the indictment, held the indictment to be in accordance with the law and that sufficient suspicion existed to warrant an investigation.

According to article 96 of the Constitution and articles 8-9 of the Constitutional Law no. 1 of 16 January 1989, it is up to the Parliament to authorize the investigation and prosecution of a Minister. The decision would therefore be up to the Senate in the case of Minister Salvini, as he is a Senator. The Senate may refuse by absolute majority, if it considers “that the person has acted for the protection of a State interest that is constitutionally relevant or for the pursuance of a preminent public interest in the function of Government” (unofficial translation). No appeal is possible against this decision.

Reportedly, the President of the Council of Ministers, Giuseppe Conte, the Vice-President of the Council of Ministers, Luigi Di Maio, and the Minister Danilo Toninelli, have submitted observations to the Senate’s Committee holding that the decision in the case was the reflecting the line of the whole Government and not only of the Minister of Interior.

Feb 15, 2019 | News

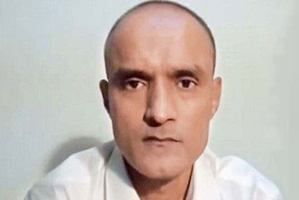

The International Court of Justice will hold public oral hearings in India v. Pakistan (Jadhav case) from 18 to 21 February 2019. Before they commence, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) has published a briefing paper to clarify the key issues and relevant laws raised in the case in a Question and Answer format.

The case concerns Pakistan’s failure to allow for consular access to an Indian national, Kulbhushan Sudhir Jadhav, detained and convicted by a Pakistani military court on charges of “espionage and sabotage activities against Pakistan.”

India has alleged that denial of consular access breaches Pakistan’s obligations under Article 36(1) of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), to which both States are parties.

Pakistan has argued, among other things, that the VCCR is not applicable to spies or “terrorists” due to the inherent nature of the offences of espionage and terrorism, and that a bilateral agreement on consular access, signed by India and Pakistan in 2008, overrides the obligations under the VCCR.

ICJ’s Q&A discusses the relevant facts and international standards related to the case, including: India’s allegations against Pakistan; Pakistan’s response to the allegations; the applicable laws; and the relief the International Court of Justice can order in such cases.

Contact:

Frederick Rawski (Bangkok), ICJ Asia Pacific Regional Director, e: frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

Reema Omer (London), ICJ International Legal Adviser, South Asia t: +447889565691; e: reema.omer(a)icj.org

Additional information

While the case at issue is limited to denial of consular access under the VCCR, it engages other critical fair trial concerns that arise in military trials in Pakistan.

The International Commission of Jurists has documented how Pakistani military courts are not independent and the proceedings before them fall far short of national and international fair trial standards. Judges of military courts are part of the executive branch of the State and continue to be subjected to military command; the right to appeal to civilian courts is not available; the right to a public hearing is not guaranteed; and a duly reasoned, written judgment, including the essential findings, evidence and legal reasoning, is denied.

The case also underscores one of inherent problems of the death penalty: that fair trial violations that lead to the execution of a person are inherently irreparable.

Download the Q&A:

Pakistan-Jadhav case Q&A-Advocacy-Analysis brief-2019-ENG