Apr 10, 2020 | News

The ICJ today called upon the Myanmar government to ensure that everyone in the country, particularly those from communities affected by conflict, has access to critical information about COVID-19. This call includes putting an immediate end to restrictions on internet access in Rakhine and Chin States.

The ICJ said that there must not be undue restrictions on the right of people to seek and impart such information, in line with international law and standards protecting the right to freedom of expression and information.

“Access to information is absolutely essential for the protection of communities, especially their right to health during the COVID-19 outbreak,” said Frederick Rawski, ICJ Director for Asia and the Pacific. “This is especially true in areas of Myanmar affected by conflict. The wholesale blocking of internet access in Rakhine and Chin States, including access to websites of popular ethnic media outlets, has no justifiable basis in international law and will only serve to undermine efforts to mitigate the spread of the virus.”

On 26 March 2020, the Minister of Transport and Communications stated in a media interview that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the internet shutdown in Rakhine and Chin States would not be lifted until hate speech, misinformation and the conflict with the Arakan Army are addressed. The Minister’s statement appears to defy the UN Secretary-General’s appeal for a global ceasefire as well as the respective statements of members of Myanmar’s diplomatic community and of several ethnic armed organizations, including the Arakan Army, to cease hostilities in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. On 9 April 2020, the UN Special Rapporteur on Myanmar called for the same.

Instead, on 30 March 2020, pursuant to section 77 of the Telecommunications Law, the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MoTC) ordered major telecommunications networks to take down hundreds of websites on the dubious ground of containing misinformation. The MoTC did not disclose the full list of websites ordered to be blocked as well as the factual and legal basis that justified issuing the order. Under Section 77, the MoTC can direct a telecommunications provider to suspend services in the event of an “emergency situation.” It is not clear whether the misinformation relates to COVID-19 or if the pandemic is the pretext for the order.

As of 1 April 2020, media outlets of the Rakhine and Karen ethnic communities were among the websites to which access was blocked from major telecommunications providers. Access to Voice of Myanmar’s website, whose editor-in-chief had faced charges under Myanmar’s Counter-Terrorism Law until 9 April 2020 for publishing an interview with the Arakan Army, was also blocked.

The ICJ has previously expressed concern at the Myanmar Government’s use of the Telecommunications Act to justify an internet shutdown in the context of the conflict in Rakhine State. This practice does not comply with human rights law and standards. The Act itself is fundamentally flawed and must be amended. Among other defects, the Act does not define the scope of an “emergency situation.”

“Keeping these overbroad restrictions in place in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic puts the government in violation of international law. It is also counterproductive to the goal of stopping the spread of the virus and minimizing its impact on the country’s most vulnerable populations,” said Rawski.

Download the statement in Burmese here.

Contact:

Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director, e: Frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

Related work:

Event: ICJ hosts workshop on fair trial rights for Myanmar’s ethnic media

Report: Curtailing the Right to Freedom of Expression and Information in Myanmar

Statement: States must respect and protect rights in fighting COVID-19 misinformation

Apr 9, 2020 | Events, News

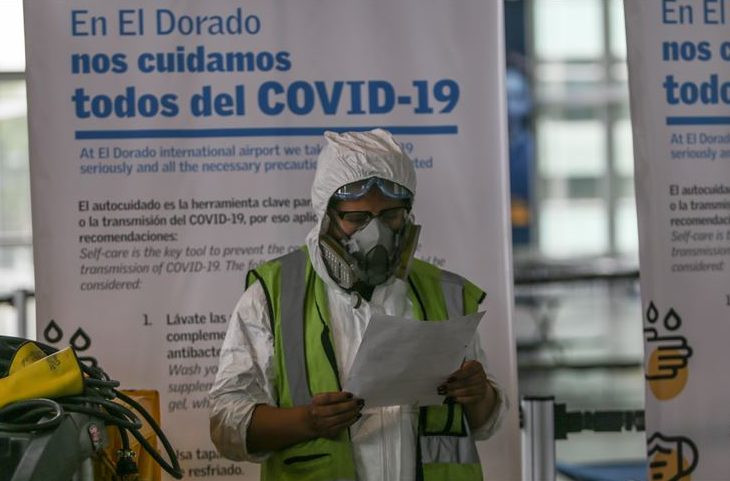

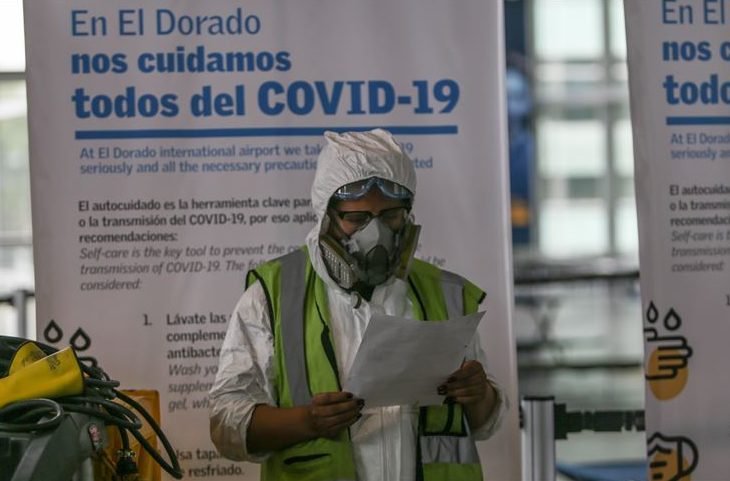

Various States in the Latin American region have adopted exceptional measures to address the pandemic and manage the health crisis. These measures impact peoples’ human rights and freedoms. A series of webinars will cover this topic. The third one takes place today.

Access to justice and the right to an effective remedy are particularly at risk. In that regard, it is worth analyzing: How are justice systems reacting to the pandemic? What is required to continue guaranteeing access to justice, especially for those people and groups most vulnerable? How does this pandemic affect the provision of services in the justice sector? How can justice systems innovate to respond to this situation?

In order to address these questions, the ICJ together with DPLF, Fundación Construir, Fundación Tribuna Constitucional, Observatorio de Derechos y Justicia, and Fundación para la Justicia y el Estado Democrático del Derecho, supports an initiative of webinars led by a group of women human rights defenders in Latin America.

The webinars will be held in Spanish and through the Zoom platform. Registrations for each webinar can be made by sending an email to info@dplf.org Registered persons will receive the zoom link where the activity can be followed.

The first three conversations are as follows:

- Essential justice services in times of emergency: Thursday 02 of April

At: 14.00 México-Central America/ 15 hours Colombia-Perú-Ecuador/ 16.00 Washington-Bolivia/ 17.00 Chile -Argentina/ 22.00 Geneva

- Working from home and being a judge: challenges for women that are judges: Tuesday 07 of April

At 14.00 México-Central America/ 15.00 Colombia-Perú-Ecuador / 16.00 Washington-Bolivia / 17.00 Chile -Argentina/ 22.00 Geneva

- Innovating in the justice system during times of emergency: Thursday 09 of April

At 14.00 México-Central America/15.00 Colombia-Perú-Ecuador/ 16.00 Washington-Bolivia/ 17.00 Chile -Argentina/ 22.00 Geneva

Apr 8, 2020 | Noticias

Por décadas, un número importante de colombianos han sido víctimas de crímenes atroces relacionados con el conflicto armado. En particular, los defensores de derechos humanos han sido blancos de violaciones de derechos humanos y abusos serios, como asesinatos, amenazas de muerte y hostigamientos.

Solo este año, la Oficina de la Alta Comisionada de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos (ACNUDH) ha recibido información sobre 56 posibles casos de asesinatos de defensores de derechos humanos. Desafortunadamente, el brote del COVID-19 no ha detenido la violencia contra defensores de derechos humanos.

Al respecto, desde el primer caso confirmado de COVID-19 en el país, el 6 de marzo de 2020, la Organización de Estados Americanos (OEA) y Amnistía Internacional han reportado el asesinato de seis defensores de derechos humanos. Los perpetradores de estos crímenes todavía no han sido identificados.

En igual sentido, las violaciones de derechos humanos y abusos contra comunidades locales tampoco se han detenido. A decir verdad, lo contrario parece ser lo cierto. Así, por ejemplo, se ha denunciado que grupos armados ilegales, incluyendo grupos paramilitares y nuevos grupos formados por disidentes de la guerrilla de las FARC-EP, están aprovechado la pandemia para cometer acciones ilegales con mayor libertad, principalmente en áreas rurales del país. Entre las acciones cometidas por estos grupos, se destaca el desplazamiento forzado de 250 personas y el confinamiento de 770 familias por los combates entre un grupo paramilitar y un grupo guerrillero. Ambas acciones tuvieron lugar en la región pacífica del país, en la cual el conflicto se ha intensificado luego del Acuerdo Final de Paz. Adicionalmente, se conoce de al menos tres desmovilizados de las FARC-EP que han sido asesinados en marzo de 2020.

A pesar de la gravedad de la situación anteriormente descrita, la respuesta del gobierno colombiano a la crisis provocada por el COVID-19 se ha centrado en la creación e implementación de medidas no relacionadas con el conflicto. Al respecto, el gobierno ha decretado regulaciones de gran importancia para mitigar los efectos sociales y económicos creados por el virus. Entre otras regulaciones, el presidente decretó un estado de emergencia y una cuarentena nacional obligatoria por 19 días desde el 25 de marzo de 2020. De igual forma, el gobierno estableció una serie de ayudas sociales y económicas en favor de quienes se verán más afectados por la cuarentena.

Ninguna de estas medidas fue diseñada considerando la situación particular de los defensores de derechos humanos. Como consecuencia, su protección no es un elemento central de las políticas colombianas para hacer frente a la pandemia. Si se considera que la implementación del Acuerdo Final de Paz y los derechos de las víctimas no son prioridades del actual gobierno, el enfoque adoptado no es completamente inesperado. En todo caso, para ser justos, se debe reconocer que los programas estatales para la implementación del Acuerdo han continuado operando durante la pandemia.

Ahora bien, podría argumentarse que la pandemia tiene el potencial de afectar predominantemente derechos humanos que no están relacionados con el conflicto armado. Por lo tanto, desde este punto de vista, la priorización de medidas no relacionadas con el conflicto armado está justificada y es requerida. Si bien esta posición se basa en una premisa valida, que es que la pandemia causada por el COVID-19 crea varios desafíos que van más allá de los problemas de derechos humanos relacionados con el conflicto, ignora un elemento central de la realidad colombiana: la existencia de un conflicto en curso.

Actualmente, el conflicto afecta directamente una parte considerable de la población colombiana, incluyendo la mayoría de los defensores de derechos humanos. Sobre este tema, fue reportado que, el año pasado, las acciones cometidas por grupos ilegales en el marco del conflicto afectaron a al menos 10 de los 32 departamentos de Colombia. En ese sentido, ignorar la importancia del conflicto puede llevar a que algunas medidas para hacer frente a la pandemia resulten ineficaces. Lo anterior, ya que, en las zonas afectadas por el conflicto, la protección de los derechos humanos requiere abordar los desafíos específicos que la pandemia ha creado en esos territorios. Por ejemplo, la presencia de grupos ilegales puede conllevar a que no se realicen pruebas para el COVID-19 a los miembros de las comunidades locales o que no puedan acceder a servicios de salud. Igualmente, debido a la cuarentena, los grupos ilegales pueden identificar más fácilmente la localización de defensores de derechos humanos y tomar represalias contra ellos.

En relación con los defensores de derechos humanos, también debe mencionarse los problemas relacionados con el acceso a medidas de seguridad adecuadas. Sobre este tema, Amnistía Internacional ha denunciado que los esquemas y medidas de seguridad de algunos defensores de derechos humanos han sido reducidos por la pandemia. De igual forma, una organización no gubernamental local expresó preocupación por la decisión de la Unidad Nacional de Protección de suspender indefinidamente las sesiones de la Comisión en donde se definen las medidas de protección.

En consideración con lo anterior, y más allá de las consideraciones políticas y de las prioridades generales del gobierno, es imperativo que el gobierno adopte una perspectiva integral para enfrentar la pandemia. Esto implica abordar el impacto diferencial que la pandemia puede tener en las personas que lideran los procesos de transformación social y legal, en las zonas afectadas por el conflicto. En particular, deben implementarse o adaptarse medidas eficaces de protección para defensores de derechos humanos durante la crisis del COVID-19. Asimismo, deben garantizarse y cumplirse los derechos de acceso a un recurso efectivo y a la reparación, de conformidad con los estándares internacionales.

Adicionalmente, el gobierno nacional debe hacer mayores esfuerzos para obtener un cese de hostilidades humanitario por parte de todos los grupos ilegales durante la crisis del COVID-19. Un cese de hostilidades humanitario contribuiría a (i) proteger a la población civil contra actos violentos, (ii) implementar las medidas relacionadas con la pandemia en las zonas de conflicto y (iii) evitar la proliferación del virus en comunidades vulnerables. Esta es una medida crucial que ya ha sido solicitada por organizaciones civiles nacionales, el jefe de la misión de verificación de Naciones Unidas en Colombia, la OEA y algunos parlamentarios. Hasta la fecha, solo un grupo armado ilegal ha aceptado un cese de hostilidades: el Ejercito de Liberación Nacional (ELN), la guerrilla activa más grande en Colombia, la cual decretó un cese al fuego unilateral durante abril.

En conclusión, reconocer la importancia del conflicto es esencial para hacer frente a las implicaciones en los derechos humanos creadas por las crisis del COVID-19. Esto es necesario para contar con políticas integrales que enfrenten la pandemia, así como para asegurar que los problemas y necesidades en las zonas afectadas por el conflicto no sean desconocidas y agravadas durante la crisis del COVID-19. Sobre este punto, como recientemente fue afirmado por el Secretario General de Naciones Unidas, debe tenerse presente que las personas más vulnerables durante un conflicto son también quienes tienen mayor riesgo de sufrir pérdidas devastadoras como consecuencia de esta pandemia.

Apr 8, 2020 | Feature articles, News

A Feature Article by Rocio Quintero, Legal Adviser, ICJ Latin American Programme, based in Bogota.

Throughout several decades, a large number of Colombians have been victims of serious crimes related to the ongoing armed conflict. In particular, human rights defenders have been targets of serious human rights violations and abuses, such as killings, death threats, and harassments.

Just this year, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has received information of 56 possible cases of killings of human rights defenders. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 outbreak has not stopped the violence against human rights defenders.

In that regard, since the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the country on 6 March 2020, the Organization of American States (OAS) and International Amnesty has reported six killings. The perpetrators of those crimes have not been identified yet.

Human rights violations and abuses against local communities have not stopped either. Quite the opposite seems to be true.

In that regard, it is said that armed groups, including paramilitary groups and new groups made up of dissident FARC-EP members, are taking advantage of the outbreak to commit illegal actions with fewer constraints, mainly, in rural areas of the country.

Among these actions, it should be highlighted the enforced displacement of 250 people and the forced confinement of 770 families due to combats between a paramilitary group and a guerrilla group. Both actions took place in the pacific region of the country, an area where the conflict has intensified after the peace agreement. In addition, at least three ex-members of the FARC-EP have been murdered in March 2020.

Despite the seriousness of the situation described above, the Colombian government response to the COVID-19 crisis has focused on the creation and implementation of non-conflict-related measures.

In that regard, the Government has decreed various and vital regulations to mitigate the social and economic impact created by the virus. Among others, the president declared a state of emergency and a mandatory 19-day national quarantine that started on 25 March 2020.

The Government also established a program of economic and social aid for those who will be affected most by the quarantine.

None of the measures were designed bearing in mind the particular situation of human rights defenders. Consequently, their protection is not a central element of the Colombian pandemic policies.

Since the implementation of the peace agreement and victims’ rights are not top priorities of the current Government, the approach adopted is not entirely unexpected.

Although, to be fair, it should be recognized that the State programmes for the implementation of the peace agreement have continued operating during the pandemic.

It might be argued that the pandemic has the potential to affect predominantly human rights that have not been directly linked with the internal conflict.

Therefore, following this point of view, the prioritization of non-conflict-related measures is justified and required.

Although this position is based on a valid premise, which is that the COVID-19 pandemic creates several challenges that go beyond conflict-related human rights problems, it ignores a central element of Colombian reality: the existence of an ongoing armed conflict.

Currently, the conflict affects a considerable part of the Colombian population directly, including the majority of human rights defenders. In that regard, last year, it was reported illegal actions related to the internal armed conflict in at least 10 out of 32 departments of Colombia.

In this context, ignoring the importance of the conflict might lead to the implementation of ineffective pandemic measures. This is because, in conflict zones, the protection of human rights requires addressing the specific challenges that the pandemic has created in those territories.

For instance, the presence of illegal groups can prevent local communities from getting tested for COVID-19 and access to health services. Likewise, due to the quarantine, illegal groups might identify easier the location of human rights defenders and retaliate against them.

In relation to human rights defenders, it should also be highlighted the problems related to access to adequate protection measures. In that regard, Amnesty International has denounced that the protection measures for some human rights defenders have been reduced due to the pandemic.

In a similar way, a local NGO expressed concerns for the decision of the National Protection Unit to suspend indefinitely the sessions of the commission where protection measures are defined.

In light of the above, beyond political considerations and the general Government’s priorities, it is imperative that the Government adopts a more comprehensive approach to tackle the pandemic.

It should address the differential impact the pandemic might have on people who lead social and legal transformations in the conflict zones of the country.

In particular, it should implement or adapt protection measures to be effective during the COVID-19 crisis. Similarly, the right to an effective remedy and reparation should also be not only guaranteed, but realized, in compliance with international standards.

Additionally, it is also important that the national Government reinforce its efforts to obtain a humanitarian ceasefire by all illegal groups during the COVID-19 crisis.

A total ceasefire would contribute to (i) protecting the civilian population for violent actions, (ii) implementing the pandemic measures in conflict zones, and (iii) avoiding a proliferation of the virus in vulnerable communities.

This is a crucial measure that has already been requested by national civil organisations, the Head of the UN Verification Mission in Colombia, the OAS, and some parliamentarians.

As yet, only one illegal group has accepted a ceasefire: the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN), the largest active guerrilla in Colombia, who declared a unilateral ceasefire during April.

To conclude, acknowledging the importance of the conflict is essential to tackle the human rights implications of the COVID-19 crisis.

This is not only necessary to have comprehensive pandemic policies, but also to make sure that the problems and needs in the conflict zones are not neglected and aggravated during the pandemic.

On this point, as recently stated by UN Secretary-General, people who are most vulnerable during a conflict are also “most at risk of suffering “devastating losses” from the disease.”

Apr 8, 2020 | News

The ICJ today warned that Cambodia’s draft Law on National Administration in the State of Emergency (“State of Emergency bill”) violates basic rule of law principles and human rights, and called on the Cambodian government to urgently withdraw or amend the bill in accordance with international human rights law and standards.

Last Friday, government spokesperson Phay Siphan explained that the government needed to bring a State of Emergency law in force to combat the COVID-19 outbreak as “Cambodia is a rule of law country”. The bill is now before the National Assembly and, if passed by the Assembly, will likely be considered in an extraordinary session convened by the Senate. The law will come into force once it has been signed by the King – or in his absence, the acting Head of State, Senate President Say Chhum.

“The Cambodian government has long abused the term “rule of law” to justify bringing into force laws or regulations that are then used to suppress free expression and target critics. This bill is no different,” said Frederick Rawski, ICJ’s Director for Asia and the Pacific.

“Any effective response to the COVID-19 outbreak must not only protect the rights to health and life, but be implemented in accordance with Cambodia’s human rights obligations and basic principles of the rule of law.”

Several serious shortcomings are evident in the State of Emergency bill, including:

- No delineation of a timeline for the imposition of a state of emergency, or criterial process for its termination. The bill provides vaguely that such declaration “may or may not be assigned a time limit. In the event that a state of emergency is declared without a clear time limit, such a state of emergency shall be terminated when the situation allows it” (article 3);

- Expansion of government powers to “ban or restrict” individuals’ “freedom of movement, association or of meetings of people” without any qualification to respect the rights to association and assembly in enforcing such measures (article 5);

- Expansion of government powers to “ban or restrict distribution of information that could scare the public, (cause) unrest, or that can negatively impact national security” and impose “measures to monitor, observe and gather information from all telecommunication mediums, using any means necessary” without any qualification to respect the rights to privacy, freedom of expression and information in enforcing such measures (article 5);

- Overbroad powers for the government to “put in place other measures that are deemed appropriate and necessary in response to the state of emergency” which can allow for significant State overreach (article 5);

- Severe penalties amounting to up to 10 years’ imprisonment of individuals and fines of up to 1 billion Riel (approx. USD 250,000) on legal entities for the vaguely defined offence of “obstructing (State) measures related to the state of emergency” where such obstruction “causes civil unrest or affects national security” (articles 7 to 9);

- No specific indication of which governmental authorities are empowered to take measures under the bill, raising concerns that measures could be taken by authorities or officials in an ad-hoc or arbitrary manner in violation of the principle of legality;

- No indication of sufficient judicial or administrative oversight of measures taken by State officials under the bill – The bill states that the government “must inform on a regular basis the National Assembly and the Senate on the measures it has taken during the state of emergency” and that the National Assembly and the Senate “can request for more necessary information” from the government (article 6) but does not clarify clear oversight procedures for accountability.

“The State of Emergency bill is a cynical ploy to further expand the nearly unconstrained powers of the Hun Sen government, and will no doubt be used to target critical comment on the government’s measures to tackle COVID-19,” said Rawski.

“If passed in its current form, this bill will reinforce the prevailing lack of accountability which defines the government in Cambodia. The government’s time would be better spent developing genuine public health policy responses to the crisis.”

Contact

Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia Pacific Regional Director, e: frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

To download the statement with detailed background information, click here.

See also

ICJ report, ‘Dictating the Internet: Curtailing Free Expression, Opinion and Information Online in Southeast Asia’, December 2019

ICJ report, ‘Achieving Justice for Gross Human Rights Violations in Cambodia: Baseline Study’, October 2017

ICJ, ‘Cambodia: continued misuse of laws to unduly restrict human rights (UN statement)’, 26 September 2018

ICJ, ‘Misuse of law will do long-term damage to Cambodia’, 26 July 2018

ICJ, ‘Cambodia: deteriorating situation for human rights and rule of law (UN statement)’, 27 June 2018

ICJ, ‘Cambodia human rights crisis: the ICJ sends letter to UN Secretary General’, 23 October 2017