Apr 8, 2013

An opinion piece by Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia-Pacific Regional Director and Benjamin Zawacki, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia.

An opinion piece by Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia-Pacific Regional Director and Benjamin Zawacki, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia.

The controversy surrounding Aung San Suu Kyi (photo) and a joint-venture copper mine project in Myanmar should give prospective foreign investors pause.

It should also prompt the international community to help the country establish a legal regime on which both investors and the people of Myanmar can rely for protection of their rights.

A government-backed investigation into the mine project, chaired by Suu Kyi, concluded that security forces used chemicals against villagers protesting against it.

It also recommended additional impact assessments, and either increased compensation or the return of farmland allegedly taken via fraud and coercion.

But, crucially, it concluded that the project should continue. Villagers vehemently disagreed and vowed to pursue a lawsuit.

Myanmar’s government has a duty to protect workers, consumers, landholders and indigenous people against rights violations.

Despite recent steps, however, there are not enough lawyers, judges and others adequately trained to monitor economic activity and provide accountability for violations of laws governing corporate action.

Corporations have a strong interest in supporting the development of robust accountability mechanisms in Myanmar.

Many now considering investing participate in a global corporate citizenship initiative known as the UN Global Compact, which asks its members to take action prior to investing, such as human rights and environmental impact assessments, and to monitor business activity once under way.

Yet all the compact’s “commitments” are non-binding. And even strict adherence would not serve as a defence for companies accused of committing human rights and environmental violations.

Increasingly, transnational corporations may be held legally responsible for abuses in the country where they occurred, and also in their home country.

Western companies are the most vulnerable, but the copper mine case shows Asian enterprises are not immune: the mine’s other joint-venture partner is the Chinese Wan Bao mining company, a subsidiary of weapons manufacturer Norinco.

The copper mine controversy also shows that the line between “government” and “company” in Myanmar can be blurry; large joint ventures often include the military-owned Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Company.

Indeed, the army is deeply involved in many companies and has a long record of human rights and humanitarian law violations.

In one landmark case, villagers sued Unocal in a US court for complicity in security forces’ human rights violations during the construction of the Yadana gas pipeline.

The case was settled in 2004 before a final decision on liability was reached. What made it significant – and still relevant – is that the US law used is not limited to US corporations.

The Unocal case was allowed to progress in the US because the courts found that the judicial system in Myanmar was not independent of the military government of the time and therefore could not provide a proper venue for a lawsuit.

Today, despite ongoing legal reform, there is a long way to go to rebut this finding.

The copper mine case presents an opportunity for the judiciary to demonstrate whether it can render just decisions.

Investment in Myanmar, if done lawfully and with reliable legal remedies, can be a strong force for good.

The international community should support Myanmar’s reformers in making this happen.

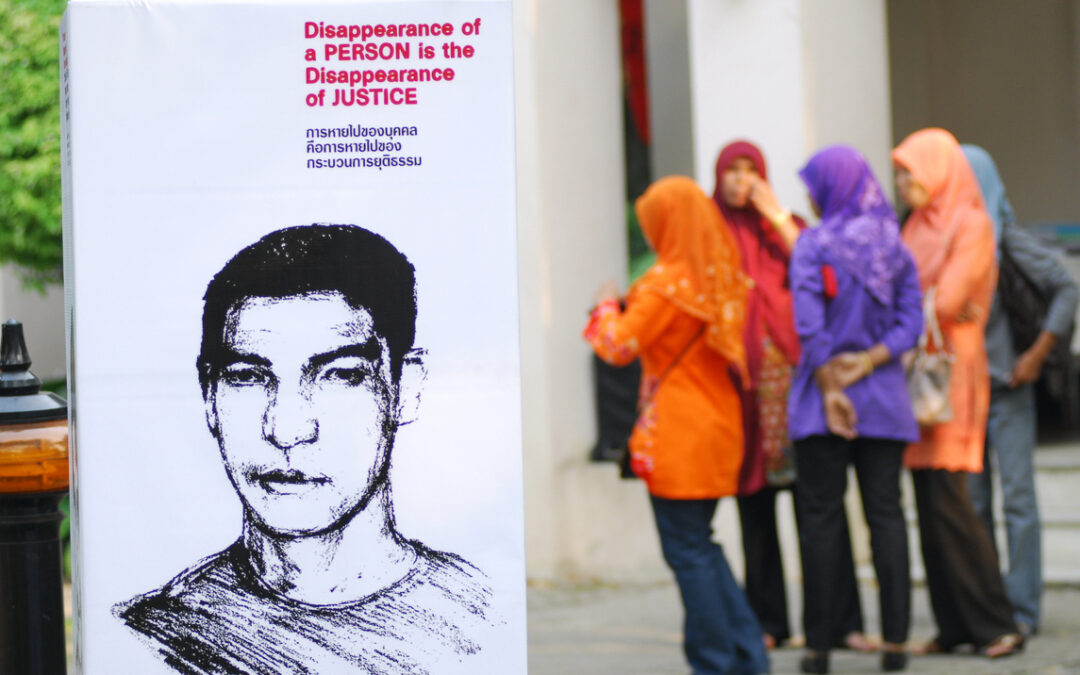

Jan 14, 2013

An opinion piece by Frederick Rawski, ICJ Nepal Country Representative, and Paul Seils, Vice President of the International Centre for Transitional Justice.

Rather than resist UK efforts to implement its obligations under international law, the Nepali government should develop a transitional justice programme to provide truth, justice and reparations.

As attested by last week’s arrest in the United Kingdom of Kumar Lama, a Nepali Army Colonel suspected of torture, the government of Nepal’s failure to pursue truth and accountability for conflict-era violations can have serious consequences.

If victims of serious human rights violations are unable to obtain an effective remedy in Nepal and the government continues to ignore their rights to truth, justice, and reparations, they will inevitably seek other avenues, including the pursuit of perpetrators in other countries.

Rather than resisting UK efforts to implement its obligations under international law, the Nepali government should develop a full transitional justice programme and redouble its efforts to provide truth, justice and reparations inside the country.

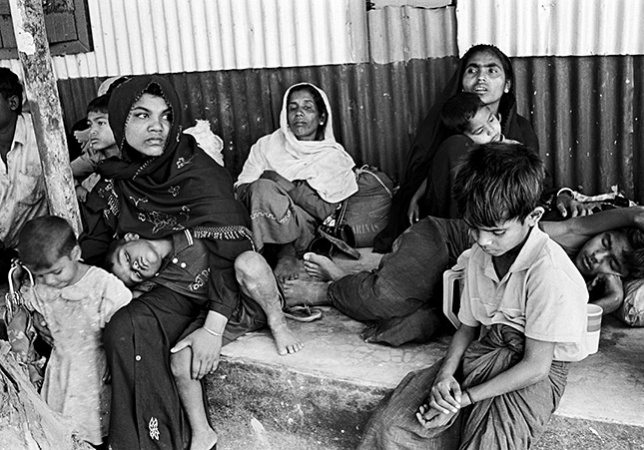

Nepal’s 10-year armed conflict between the Communist Party of Nepal- Maoist and state security forces saw systematic violations of international human rights law and serious breaches of international humanitarian law.

Some 13,000 people were killed, thousands more were tortured and displaced. Approximately 1,300 persons remain missing or disappeared.

Six years on, in spite of specific provisions in the peace agreement, the government of Nepal has failed to initiate investigation into the past.

Following Col Lama’s arrest, the Nepali government has again insisted that it will meet its international obligations by establishing a truth commission.

Three points to clarify

It is in this context that we write to clarify three points relating to transitional justice processes that are often misunderstood.

First, the state’s acknowledgement of the truth about conflict-era crimes is a right of victims and Nepali society as a whole, not a matter of charity. The state has a duty to fulfil the right to the truth, which must be done through an official mechanism in order to ensure official recognition.

Second, the search for truth, if carried out in good faith, can support efforts to achieve other rights of conflict victims, including to justice, reparations and the guarantee of non-reoccurrence.

Third, the work of a truth commission does not substitute for prosecutions of war crimes, crimes against humanity or other serious crimes under international law, including cases of torture, as alleged to have been perpetrated by Col Lama.

The search for truth is based on the right of victims, their families and society to know how and why terrible violations of human rights took place.

What happened? Who allowed these things to happen? And what have been the consequences for victims and families? The state has a duty to answer these questions, and victims have a right to search for and demand answers. For this reason there should be continued pressure for an official truth mechanism that complies with international law and incorporates best practice.

The Nepal government’s latest proposal, an ordinance for a combined disappearance and truth commission, does not satisfy these requirements.

Instead, it opens the way to a back-door route to amnesty for perpetrators of serious crimes and possible coerced “reconciliation”.

However, this does not mean that prospects for a truth commission should be written off. Rather, the ordinance should be withdrawn and efforts renewed to strengthen proposals, in consultation with civil society, to establish at the earliest opportunity a credible, effective and independent truth mechanism, or mechanisms.

Measures needed

However, an integrated transitional justice process means that truth seeking must be accompanied by measures to act on this knowledge-measures including criminal trials and reparations that contribute to preventing violations from taking place again.

The UN’s Un Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence of serious crimes and gross violations of human rights, Pablo de Greiff, has emphasised this point.

He has called on states to resist the tendency to think of transitional justice as ” a soft form of justice” and warned against selectivity about which measures to pursue.

In Nepal, criminal investigations and prosecutions can and should proceed with or without a truth commission.

Unlike many other countries in transition, Nepal has the advantage of a functioning judiciary that has taken courageous decisions on important conflict-era cases. Likewise, measures to reform institutions, including the removal of individuals suspected of involvement in human rights violations, do not depend on the establishment of a truth commission.

Nepal’s Supreme Court already ruled in August 2012 that the promotion of security officials should depend on their human rights record.

Victims in Nepal continue their efforts to search for and speak the truth, as witnessed by frequent events to remember the ” disappeared “, commemorate the dead and petition the courts. Yet despite repeated commitments, the Nepal government has yet to deliver.

Elsewhere when official’s processes have stalled or there has been a lack of confidence in them, civil society has initiated unofficial truth projects.

Because they are not alternatives to officials truth-seeking, they do not in any way limit or relieve the state of its obligations to guarantee the right to truth.

Rather, two decades of global experience shows that unofficial efforts can put additional pressure on the state to fulfil its duty regarding victims’ rights.

How? By raising voices publicly and providing solid documentation about serious crimes and their consequences.

The impact may be small on a national scale, but for individuals, it can mean an assertion of their own dignity and that of their loved ones.

Equally important, they help to maintain these crimes and the need for redress in the public agenda.

For the sake of these victims, their families and Nepali society as a whole, Nepal must not let up on efforts to establish official truth – seeking processes, advance court-ordered prosecutions and create a reparation programme.

Contrary to the views of some, pursuing justice is not about vengeance, but rather about moving forward on the path to a stable democracy, where individuals can trust state institutions knowing that their rights are protected.

An opinion piece by Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia-Pacific Regional Director and Benjamin Zawacki, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia.

An opinion piece by Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia-Pacific Regional Director and Benjamin Zawacki, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia.