An opinion piece by Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director.

An opinion piece by Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director.

An awkward silence in a small restaurant in Yangon: The veteran dissident and pro-democracy activist had just explained why he does not have much sympathy for the Rohingya despite the widespread and systematic violence they have faced, because, as he saw it, ‘Rohingya’ is a ‘made up’ name’ and ‘they are all illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and they should go back there.’

He is not at all unique. During our recent visits to Burma – now called Myanmar by its government – we heard this blatantly racist sentiment repeatedly, including from lawyers and activists who apparently saw no contradiction between demanding human rights and greater rights for the country’s beleaguered ethnic minorities while, at the same time, denying such rights to the Rohingya.

Two weeks ago, even Buddhist monks marched in downtown Yangon to demand expulsion of the Rohingya.

It is difficult to change such attitudes by confronting them directly, as tempting as it may be. What we have found is that a better response is pointing to international human rights standards – the same standards that many dissidents and activists in Myanmar have been invoking in their own defense – and explaining that these standards should be applied to all, regardless of their ethnicity or legal status.

It is crucial for the Myanmar government, as well as opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, to publicly announce—and demonstrate—their commitment to these standards and begin the work of getting public acceptance for them, for all people living in Myanmar.

The discrimination against the Rohingya has been egregious in Myanmar for years, as they have been rendered stateless under the country’s 1982 Citizenship Law, which denies them Myanmar citizenship and thus severely curtails their right to hold property, or enter school, or even get married.

Most recently the issue has gained increased urgency because of bloody clashes between the Muslim Rohingya and Buddhists in resource-rich Arakan state.

According to reports from credible sources, including Tomas Quintana, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the situation in Myanmar, armed gangs from both communities killed dozens, burned down several villages, and displaced tens of thousands of people while government security forces stood by, or worse, in some cases targeted the Rohingya.

In the face of such virulence, even Aung San Suu Kyi, the human rights icon and Nobel Peace laureate, has been uncomfortably ambiguous, calling only for ‘the rule of law’ to determine the Rohingya’s citizenship status. Her perceived silence has tarnished her halo, as international observers have criticized her for failing to stand up for the rights of a historically abused minority group.

From inside the country, however, Aung San Suu Kyi’s vacillation is more easily understood (though not excused). At this point she is a clear beneficiary (and somewhat surprising co-sponsor) of the remarkable reforms pushed by President Thein Sein. She is a member of parliament now, which her party, the National League for Democracy, has every expectation of dominating if open elections are held. She is also viewed as a strong candidate for the country’s leadership, should the reform process continue.

In such a position, she is severely constrained in what she can say to maintain her support among her political base and future voters. The Buddhist monks who marched in Yangon against the Rohingya were mostly drawn from a faction of activist monks who have supported Aung San Suu Kyi in her opposition to the government (most notably during the 2007 ‘Saffron Revolution’), but were also noted for consistently advocating violence against Muslims. They would likely press Aung San Suu Kyi strenuously to avoid any conciliatory language.

The hatred against the Rohingya is most pronounced, but a quick glance at media inside the country, now freer from government constraints, shows that racism is already prevalent and growing: there are frequent attempts to cast Chinese migrants allegedly entering Kachin State, or Indians from Manipur, as scapegoats for economic problems or the drug trade.

Myanmar’s government understands, as well as Aung San Suu Kyi, that ethnic and sectarian tensions pose a serious threat to the country’s economic development and its reform process. As hard as it may be, both Aung San Suu Kyi and the government must begin to curb this problem immediately.

This is precisely where international law and standards can be of immense value. There is enormous desire inside the country to end the country’s isolation, and a major part of that is cleaning up the country’s terrible human rights record.

One of the bedrock principles of international human rights is that governments cannot discriminate on the basis of religion or national origin. This is one of the pillars of international law, including the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Notwithstanding the legal status of the Rohingya, or any other ethnic and religious groups, they are protected by international law, and the government of Myanmar is obliged to protect their rights.

Myanmar’s leaders must begin publicly embracing these standards. Moreover, pro-democracy activists and human rights defenders within the country must also start realizing and begin to acknowledge that the same standards that were invoked to protect tens of thousands of refugees and asylum seekers from Myanmar in neighboring countries, such as Thailand, China, and India, also apply inside the country’s borders.

Public information campaigns about human rights thus would benefit both the government as well as the political opposition.

There are still tremendous human rights problems in Myanmar, ranging from incarceration of political critics and disbarring of activist lawyers, to war crimes in the grinding internal conflicts between the army and armed ethnic groups, to massive institutional failure to alleviate the country’s crushing poverty and high rates of maternal and infant mortality. But there is hope now that these problems can be addressed if the current trend toward reforms continues.

The people of Myanmar would greatly benefit from understanding that these rights apply to all, regardless of ethnicity or citizenship, and that their government will demonstrate in practice its commitment to implement these rights.

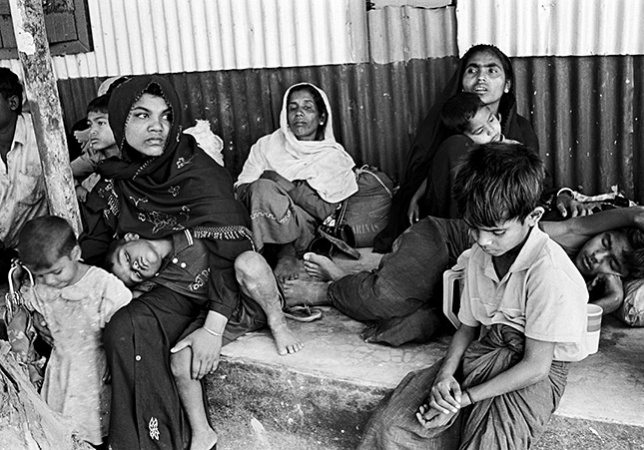

Photo credit: © Greg Constantine