Feb 24, 2021

An opinion piece by Roojin Habibi, Benjamin Mason Meier, Tim Fish Hodgson, Saman Zia-Zarifi, Ian Seiderman & Steven J. Hoffman

In the COVID-19 response, leaders around the world have resorted to wartime metaphors to defend the use of emergency health measures . Yet, as the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) has noted, States have seldom taken into account corresponding obligations under international human rights law when formulating their ‘call to arms’ against an elusive new enemy.

In assessing the appropriateness of health measures that limit human rights, human rights defenders, academics, international organizations and, most recently, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus have all looked to the Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogations Provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Developed in 1984 through a consensus-building effort among international law experts co-convened by the ICJ, the Siracusa Principles sought to achieve “an effective implementation of the rule of law” during national states of emergency, constraining limitations of human rights in government responses. The Siracusa Principles are aimed at ensuring that emergency response imperatives are taken with human rights protections as an integral component, rather than an obstacle. The Principles have since been incorporated into the corpus of international human rights law, in particular through the jurisprudence of the UN Human Rights Committee. They have come to be widely recognized as the authoritative statement of standards that must guide State actors when they seek to limit or derogate from certain human rights obligations, particularly in times of exception – including those states of emergencies that “threaten the life of the nation.”

Framing global health law to control public health emergencies, the World Health Organization’s International Health Regulations (IHR) have long sought to codify international legal obligations to guide responses to infectious disease threats. The IHR, last revised in 2005 in the aftermath of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak, bind states under global health law to foster international cooperation in the face of public health emergencies of international concern. This WHO instrument, which in general terms must be implemented with “full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedom of persons,” seeks to prevent, detect, and provide a robust public health response to disease outbreaks while minimizing interference with international traffic and trade. Yet, the agreement that is legally binding on 194 states parties has been all but forgotten amid the biggest pandemic in a century, with its legal limitations exposed in this time of dire need.

The lack of certainty regarding the scope, meaning and implementation of international human rights obligations during an unprecedented global health emergency has enabled inappropriate and violative public health responses across nations. As the world’s struggle against the coronavirus stretches on, we must begin to consider how global health law and human rights law can be harmonized – not only to protect human dignity in the face future global health crises, but also to strengthen effective public health responses with justice.

The necessarily multi-sectoral response to COVID-19 reveals the distinctive nature of interpreting human rights limitations in a global health emergency that (1) is an international (compared to a national) phenomenon; (2) endangers not only civil liberties and fundamental freedoms, but a broad range of health-related human rights, including the right to health itself; and (3) challenges governments to assess proportionate public health responses in situations of scientific uncertainty.

Global health emergencies raise the imperative for global solidarity

It has proven challenging to ensure that States comply with international standards for permissible human rights limitations amid an emergency that extends across all nations. As a set of standards that primarily guides State conduct in response to national threats to public welfare and security, the Siracusa Principles do not fully contemplate and provide for today’s lived experience in which an international emergency has infiltrated every continent. Similarly, although the IHR make explicit the international duty to collaborate and assist in addressing global health threats, a lack of textual clarity and general failing among states parties to operationalize this obligation render the provision devoid of meaning.

Global solidarity through international cooperation is both a human rights imperative and a global public health necessity. Breakdowns in the international commitment to hasten the supply of COVID-19 vaccines to all States, however, portend future struggles in achieving unity among nations against a common danger. As a number of UN Human Rights Council experts warned in late 2020, “[t]here is no room for nationalism or profitability in decision-making about access to vaccines, essential tests and treatments, and all other medical goods, services and supplies that are at the heart of the right to the highest attainable standard of health for all.” In the coming decades, the world will inevitably face increasing, intensified, and interconnected planetary health threats, including not only the emergence of new infectious diseases, but also the evolution of highly drug-resistant microbes, environmental degradation, climate change, and biological weapons proliferation. Since no country can face these perils alone, overcoming them will require robust, science-based and enduring international cooperation within the framework of “a social and international order in which rights can be fully realized.”

Global health emergencies call for dedicated focus on health-related rights, including the right to health

Nearly all governments have resorted to physical distancing policies to control the spread of disease. While ostensibly adopted to protect public health, such interventions have rarely been accompanied by social relief programmes, such as income support and debt suspension, that are necessary to avoid collateral damage to economic and social rights, including the rights to health, social security, work, and housing. Instead, responses to the pandemic have largely magnified the fault lines of racial, socioeconomic, disability, gender and age inequalities, intensifying the suffering of those already at greatest risk and falling short of State obligations to ensure that responses to public health emergencies do not have discriminatory impacts. However, neither the Siracusa Principles nor the IHR give sufficient attention to the breadth of health-related human rights imperilled by an emergency response. The Siracusa Principles are expressly addressed to limitations of civil and political rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the IHR never mentions the right to health or economic, social and cultural rights, despite WHO’s constitutional mandate to advance the right to health – including the social determinants of health – being central to global health governance.

More than 30 years ago, the HIV pandemic imparted crucial lessons to the world on the intricate linkages between health and human rights. These lessons reverberate once again in the current crisis, reinforcing the interdependence of all human rights as a foundation for global health. Bearing obligations to realize collective rights to public health in a pandemic response, how should States consider the impact of public health emergency measures on their indivisible obligations to realize economic, social, and cultural rights, including the right to health and its underlying determinants? Given the rapid privatization of basic healthcare services and the interests that pharmaceutical companies hold over global vaccine distribution, what are the responsibilities of private actors in the context of public health emergencies? Global health law and human rights law must converge to account for limitations to economic, social, and cultural rights that underlie public health in the context of global health emergencies, and advance effective legal remedies to ensure accountability for the unjustified violation of all human rights in the public health response.

Global health emergencies challenge proportionality assessments in a moment of scientific uncertainty

Under the Siracusa Principles, public health emergencies allow for measures that restrict human rights only to the extent they are “necessary” – that is, measures responding to “a pressing public or social need,” in pursuit of “a legitimate aim,” and “proportionate to that aim.” Government responses to global health emergencies, however, are strained by high degrees of scientific uncertainty, especially at the outset of emerging disease outbreaks. The IHR, much like the Siracusa Principles, evaluates the proportionality of public health measures by requiring that they be no more restrictive of international traffic and no more invasive or intrusive to persons “than reasonably available alternatives,” but it further calls for their implementation to be based on “scientific principles,” “scientific evidence,” and “advice from the WHO.” However, even the IHR’s explicit consideration of scientific knowledge in the proportionality criteria have failed to guide policy actions in the pandemic response.

Selective travel restrictions, for instance, have become the prima facie response not only to the containment of the original SARS-CoV-2 virus, but also to its more transmissible and possibly more lethal variants – despite the discouragement of targeted travel bans under the explicit language of the IHR, mixed scientific evidence of their effectiveness in the absence of other non-pharmaceutical interventions, and historical lessons on their potential to disincentivize the reporting of future outbreak. Measures justified by public health concerns, of which travel restrictions are but one example, if improperly conceived and implemented, may lend themselves to politicization, ineffective or counterproductive public health impacts, discriminatory use, and human rights violations – fracturing the world and distracting from a united and sustainable response to common threats. Moreover, the scientific uncertainty that is inherent to global health emergencies is likely to challenge our conception of how long de jure or de facto national states of emergency may last, and by extension, how to maintain the rule of law, democratic functioning of societies, and realization of the right to health and health-related rights such as access to food, water and sanitation, housing, social security, education and information under such strained conditions.

To hold governments accountable for their management of prolonged global health emergencies, more nuanced normative guideposts are needed. Building on global appeals for public health responses that are anchored in transparency, meaningful public participation, and the “best available science,” careful consideration must especially be given to bridging understandings of “proportionality” under human rights law and global health law.

Harmonizing Approaches in Human Rights Law and Global Health Law: A Call to Action

The COVID-19 pandemic is a harbinger of the evolving nature of emergencies in the 21st century and beyond. Building on the Siracusa Principles and the IHR, any subsequent restatement of the law must take into account these changing circumstances. The pandemic provides an opportunity to clarify human rights law and develop global health law in step with pressing threats to human dignity and flourishment in the modern era. Processes to update, nuance and supplement the Siracusa Principles and IHR are important to this process – providing an opportunity to harmonize human rights assessments across human rights law and global health law.

Working together across legal regimes, the ICJ and the Global Health Law Consortium are developing a consensus-based restatement of principles, drawn from international legal standards, to ensure the harmonization of public health and human rights imperatives as world leaders reconsider the role of international law in guaranteeing rights-based approaches to the inevitable public health emergencies of the future. While the microbe is natural, public health is the product of human will, and in the words of Camus, “of a vigilance that must never falter.”

The ICJ-GHLC invites readers to submit their thoughts, suggestions and/or feedback on a set of principles for global health emergencies to feedback@globalstrategylab.org

Originally published in OpinioJuris on 24 February 2021 here.

Feb 23, 2021

An opinion piece by César Landa, ICJ Commissioner from Peru.

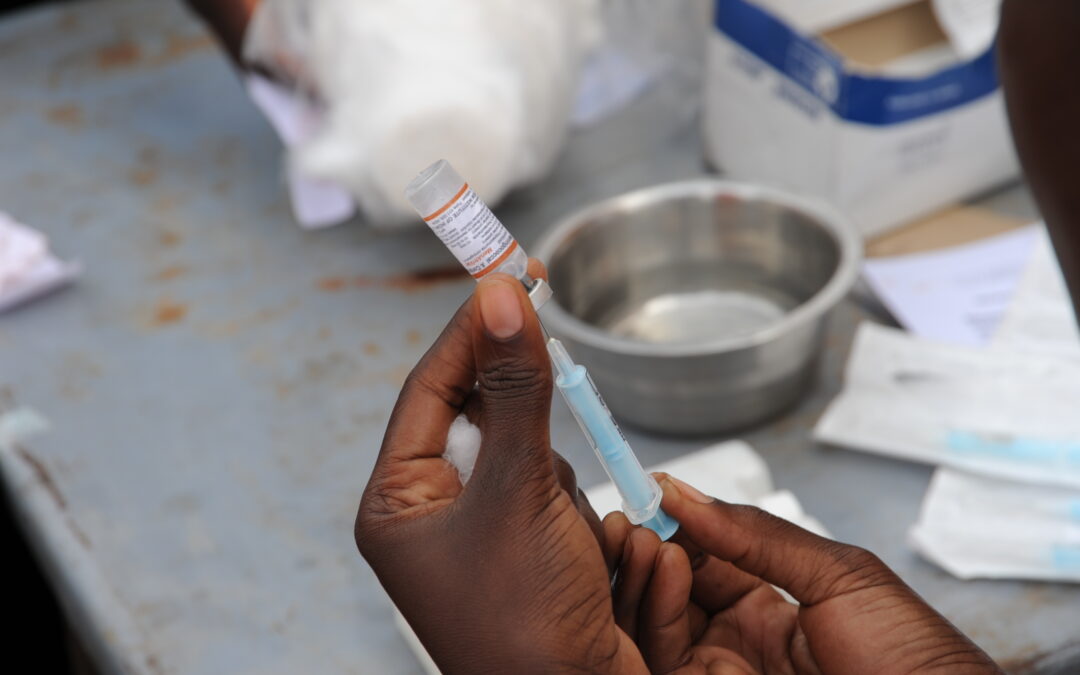

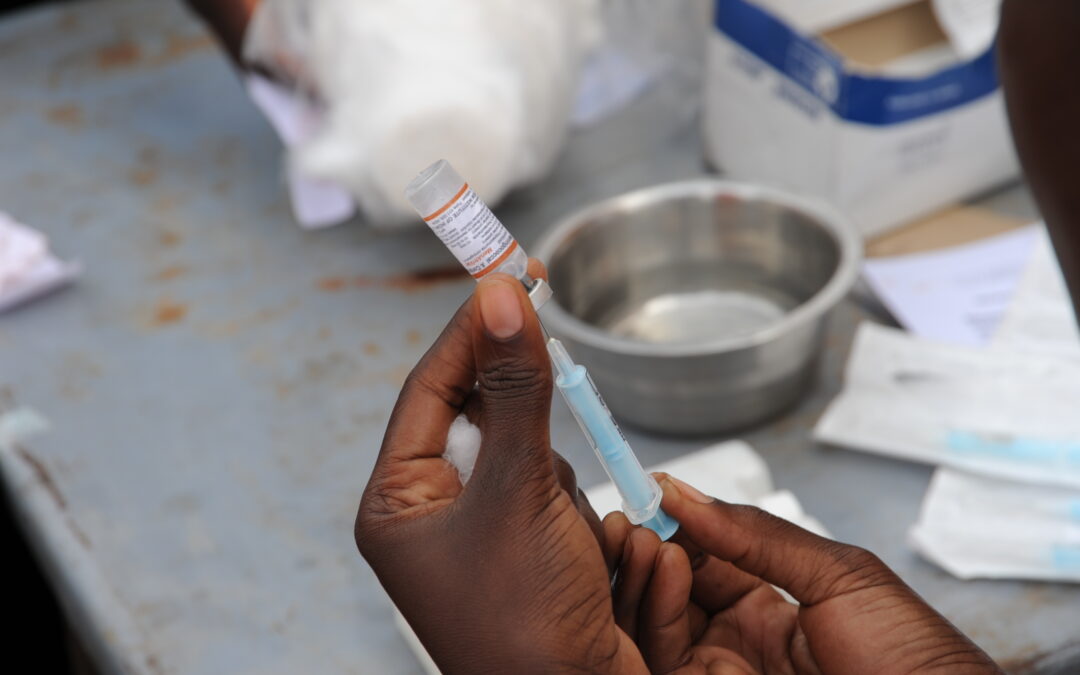

Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in millions of infections and deaths across the globe. In response to this crisis, there have been rapid development and production of vaccines in some countries of the global North and governments have approved and emergency use of the vaccines. However, vaccine distribution has been unequal at the national and international levels.

Since COVID-19 vaccines are scarce and much demanded goods, widespread access to them is treated as a national achievement by various Latin American governments, including Peru. In the case of Peru, it is important to note that since the introduction of the clinical trials of the Sinopharm vaccine, media sources have reported that, between September and January, approximately 500 people from the Peruvian elite have been vaccinated secretly. These individuals include politicians, including former President Vizcarra, two ministers and candidates for Congress, authorities of the two universities leading the clinical trials, and high-level public servants of the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Foreign Affairs. These secret vaccinations were applied with a clear disregard for health workers and individuals in vulnerable conditions, who are most in need of the limited available vaccines.

The Peruvian case demonstrates the need to consider vaccines as an essential health product that requires the application of a human rights-based approach to guarantee universal and equal access to the vaccine, in line with international standards as argued by the International Commission of Jurists. A human rights-based approach requires some essential standards for the purchasing of effective and safe vaccines. These include, for example, the purchasing of vaccines from different suppliers; transparent negotiations, without confidentiality clauses, to prevent acts of corruption; access to vaccines for all without discrimination of any kind, including persons in vulnerable conditions, such as undocumented persons or prisoners; accountability mechanisms for public and private vaccination, which should include the access to effective judicial remedies in case of failure to provide non-discriminatory and equal access to the COVID-19 vaccine.

Equal access to vaccines is critical in both the global north and south. Mass-vaccination provides the singular, most effective measure to prevent a new global COVID-19 wave. Moreover, it will facilitate everyone’s ability to fully enjoy civil and political rights, which has been greatly compromised due to the pandemic. The rights impacted include the right to freedom of movement, the right to freedom of assembly and, the right to liberty. Critically, mass-vaccination will contribute to the protection of economic, social, and cultural rights, including the right to health, work, and education, particularly, in the case of persons in vulnerable conditions.

Although it is impossible to ensure immediate access to COVID-19 vaccines for everyone, it is not acceptable that, to date, more than 130 countries have not been able to acquire or receive a single vaccine dose. This is mainly a result of the fact that ten countries have acquired 75% of all available doses, according to the United Nations Secretary-General.

Since the mass production and distribution of vaccines are enormously high in cost, only a few of the wealthiest countries of the global north have had the means to invest in development and supplies from large pharmaceutical corporations. Only through such measures has it been possible to develop vaccines in record-time and consolidate administrative procedures as well as health controls and emergency approvals. Furthermore, vaccines from developing countries such as China, Russia, and India have also entered the market with parallel autonomous research, production, validation, and commercialization processes.

In light of the above, two main challenges need to be solved using the universal human rights framework. First, the implementation of an international system for the protection of health to promote the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines in developing and most vulnerable countries that have not acquired vaccine doses. To do so, the system should use the Global vaccine mechanism COVAX, supported by the World Health Organization.

Second, it should be ensured that the national vaccination plans prioritize health care workers and others who provide emergency care. Similarly, people at greater risk of developing serious illnesses from Covid-19 should be prioritized. This includes older persons, people with existing conditions that place them at risk, persons living in poverty, indigenous peoples, racial and ethnic minorities, migrants, refugees, displaced persons, prisoners, and other marginalized and disadvantaged people.

At the moment, COVID-19 vaccines are scarce goods. However, this should not be used as an excuse by Governments to only protect their inhabits’ right to health and right to life. Humanity cannot return, even temporarily, to a Hobbesian state of nature in which “man is wolf to man”. On the contrary, the current situation, with the life and health of billions of people are at risk, requires and appeal to international solidarity based on human dignity.

Download the Op-Ed in English and Spanish.

Dec 8, 2020

An opinion editorial by Carolina Villadiego Burbano, ICJ Latin America Legal and Policy Adviser, and Carlos Lusverti, ICJ consultant.

Around the world, women’s human rights have been severely and adversely affected during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Venezuela is no exception to this trend.

The more general ongoing human rights crisis that Venezuela has faced since 2014, which has had a disproportionate impact on women and girls, and the COVID-19 pandemic and the sometimes ill-conceived government measures to tackle the pandemic have combined to aggravate the situation of women’s human rights.

This was recently well expressed in a 2020 October Resolution on Venezuela by the UN Human Rights Council. It is against this backdrop that we discuss the health risks and the gender-based violence that women are facing during the pandemic in Venezuela with the aim to provide some recommendation for authorities.

Health risks for women

According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), women in Latin America are “particularly affected by the pressure on health systems because they account for 72.8% of people employed in the sector in the region”.

The Venezuelan healthcare system was in a critical state before the COVID-19 pandemic engulfed the country, and the pandemic has aggravated the situation. For many years, several institutions and organizations have been expressing about the dire state of the health system in the country.

Since the pandemic struck, the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) and Human Rights Watch have called on the need to protect Venezuelans’ rights to health; the OHCHR has provided similar statements.

During the pandemic, the already limited health services have been primarily focused on responding to COVID-19. This has resulted in a diminished access to non-COVID-19 related health services, including those needed for sexual and reproductive care and for pregnant women.

A group of 91 Civil society organizations and additional individuals have expressed concerns about cases of pregnant women suspected of COVID-19 who have been denied timely care and the suspension of pre and postnatal care services in maternal health centers.

They stressed the need for the authorities to act to guarantee women’s rights, including access to sexual and reproductive care for women and girls.

Also, women in disproportionate numbers are responsible for dependents or people in need of care within their homes, and this has exposed them to additional risks during the pandemic.

The Asociación Venezolana de Educación Sexual Alternativa (AVESA), a local NGO, documented how the lockdown/quarantine measures increased home care tasks and deepened the economic problems women were already experiencing.

It is clear the Venezuelan authorities must act more effectively to protect women’s rights during the pandemic in line with their legal obligations under international human rights law.

Venezuela is party to several human rights treaties that provide for this legal obligation, including the Inter-American Convention for the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (“Convention of Belém do Pará”) and the UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (“CEDAW”).

The CEDAW Committee has stated that States should “address the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on women’s health”; “provide sexual and reproductive health as essential services”; “protect women and girls from gender-based violence”; and “strengthen institutional response, dissemination of information and data collection”, among other recommendations.

Additionally, Venezuelan authorities should adopt policies related to the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 with gender perspective, considering the intersectional approach and the different contexts in which may women live in Venezuela, including situations of poverty.

Also, authorities should ensure proper resource allocation to the health system, guarantee the health right of the health workers, and provide sexual and reproductive health services for all women.

Home is an unsafe place for women

In 2019, Venezuelan civil society organizations reported that in 58.6% of the cases of violence against women, the perpetrators were their current partners; and in an additional 7.7% of the cases, the attacks were perpetrated by former partners.

According to the media monitoring done by COTEJO, during that year around 107 women were victims of femicides.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFP) representative in Venezuela said that during the first semester of 2020 there were more femicides than people dying from COVID-19. Also, the Attorney General’s office reported on 185 cases during 2020.

From the start of the pandemic and until early October, most courts and tribunals were closed. As a result, women faced even greater obstacles in securing access to justice.

The OHCHR has reported that it observed “a lack of due diligence in investigative proceedings related to cases of gender-based violence” in Venezuela.

In addition, as reported by the Centro de Justicia y Paz (CEPAZ), a local NGO, there are several obstacles for access to justice for women, including the dereliction of police responsibilities when women go to file complaints or the lack of rapid answers from prosecutors that result in victims needing to repeatedly to ask them for information.

The Venezuelan authorities must better tackle gender-based violence according with their legal obligations under international law, including the Inter-American Convention of Belem Do-Pará that stresses that the state must “apply due diligence to prevent, investigate and impose penalties for violence against women” (Article 7b).

Also, authorities should do better to ensure that the justice system provide services for women victims of gender-based violence, including the adoption of specific protocols for the effective investigation and the protection of victims.

Venezuelan authorities should comply with the recent ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (Lopez Soto case of 2018), and must implement compulsory permanent training programs for public servants that work in the justice and the health care systems, who intervene in cases of women victims of any type of violence.

Finally, Venezuelan authorities must allow the legitimate action of the humanitarian organizations, who can provide humanitarian aid with gender perspective during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Venezuela-Women at Risk-News-op-eds-2020-ENG (full op-ed in PDF)

Oct 27, 2020

An opinion piece by Boram Jang, Legal Adviser at the ICJ Asia & the Pacific Programme

On 15 October 2020, the Sri Lankan authorities imposed a curfew in parts of Katunayake Free Trade Zone (KFTZ) after hundreds of workers at the Brandix Fashion Ware factory in Minuwangoda tested positive for COVID-19. More than 1500 people connected to the garment factory have been infected with COVID-19 since October 9, and four factories, Chiefway Katunayake, Next Manufacturing, Naigai and Okaya Lanka, shut down.

Many KFTZ workers migrate from rural areas in Sri Lanka, and live in overcrowded boarding houses with minimum facilities. Some of these also accommodate pregnant women and mothers with their children. In an attempt to control the spread of Covid-19, the military was called in on 11 October to round-up workers, late at night and early in the morning, to forcibly take them to makeshift quarantine centers.

According to the media and civil society reports, soldiers raided the workers’ boarding rooms, telling them they had five to ten minutes to pack their bags. The workers boarded crowded buses and headed for quarantine centers which were not established according to procedures established by law.

Trade unions and human rights activists spoke out that during this course of action by military, the workers were not informed where the center was located nor provided with protective masks. They weren’t allowed to speak at all and children were separated from their mothers.

When the workers arrived at the center, they were given some food, which many workers found inedible. The facility itself had not been cleaned, toilets were flooded and unsanitary, and no polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests had been conducted on any of the workers upon their admission to the center. In short, the military-led response to the threat of infection ended up subjecting the workers to greater threat of contagion as well as numerous indignities.

A more sensible way forward is to ensure that responses to the pandemic comply with human rights principles, especially as we hear of more accounts of inappropriate or heavy-handed military behavior in reaction to this public health crisis.

The manner in which the Sri Lankan government and the military have handled the recent outbreak among the workers has been deeply troubling. The lack of clear information provided to the workers, unsafe transportation, unsanitary quarantine facilities established without a legal basis, and failing to conduct tests prior to loading workers onto buses and upon admission to the center, and absence of judicial oversight is in clear violation of basic COVID-19 regulations adhered by the government.

At the heart of all these problems, a heavily militarized and politicized COVID-19 response lies.

In March, Sri Lanka’s first case of COVID-19 was reported. The government set up the National Operation Centre for Prevention of COVID-19 Outbreak (NOCPCO) to prevent the spread of the disease. However, instead of putting a medical professional or civil officer in charge of the Centre, the Rajapaksa government picked Lieutenant General Shavendra Silva, an alleged war criminal, to head the NOCPCO.

Silva was the commander of the 58th Division of the Sri Lankan Army, which was identified by multiple UN investigatory bodies as having been involved in the commission of serious crimes and human rights violations during the last stages of Sri Lanka’s decades-long armed conflict which ended in 2009.

President Rajapaksa has also appointed retired and currently serving military officials to other key public sector positions including the Secretary of the Ministry of Health, the Director General of the Disaster Management Centre, and the Director General of the Customs Department.

After delaying for several weeks, a countrywide curfew was suddenly declared on March 20 without adequate steps to supply essentials goods and medicines to the people. The President also gave full powers to the police to arrest people for violating curfew.

More than Over 60,000 people have been arrested for alleged curfew violations and although most them had been released on bail, the police stated that they will be prosecuted on the advice of the Attorney General’s Department when the normal court proceedings begin once the COVID-19 epidemic is over.

The violators can be prosecuted in magistrate court and if convicted, can be imprisoned up to six months and fined up to Rs. 2000. Lawmakers argued about the curfew’s legality, but it continued to be enforced in several regions, as part of the state’s coronavirus containment strategy.

The military may have to conduct law enforcement functions during a state of emergency such as public health crisis. As the UN human rights guidance provided, the military may only be deployed in a law enforcement context for limited periods and specifically defined circumstances.

When the military conducts law enforcement functions, they should be subordinate to civilian authority and accountable under civilian law, and are subject to standards applied to law enforcement officials under international human rights law.

However, in Sri Lanka now, there is no public discussion or transparency about the actions and decisions of the military during the Covid-19 response. All decisions related to the public health crisis are being made by the NOCPCO with Silva at the helm, without any judicial or Parliamentary oversight, nor any public institutional processes informing those decisions and holding him accountable to them.

Vulnerable ethnic and religious groups are acutely affected by the militarization of the public health response. Tamil organizations and politicians have continuously called for the demilitarization of the North-East. Having the military to oversee the public health policy and to act as the State’s first responders also normalize military occupation, exacerbate the existing ethnic divides, and further deteriorate human rights in Sri Lanka.

Most of the quarantine facilities are located in the North and East of the country, which still remain occupied by the Sri Lankan military.

Despite local concerns about locating quarantine centers in areas already subject to ethnic and political tensions, the government ignored the local concerns and turned schools and educational establishments in the Northern and Eastern Provinces into the quarantine centers.

Furthermore, Muslims in Sri Lanka, have also complained about inappropriate State policies and violations of their freedom to worship. The government mandated compulsory cremations for Muslims who had died after contracting the virus, going against Islamic burial practices and World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines.

While certain limitations on human rights may be undertaken to confront the public health crisis, such limitations, in keeping with the Siracusa Principles, must be for a specific public health purpose, established by law, non-discriminatory and necessary and proportionate to addressing public health.

Sri Lanka’s involvement of the military at every level, with limited parliamentary and civilian oversight raises serious human rights and rule of law concerns. Public health officials have expressed disagreements with medical authorities in terms of statistics and strategy for managing the outbreak.

The government will only be able to implement successful public health measures and maintain public support and confidence when its policies in response to the pandemic are evidence-based, human rights compliant, and transparent.

Download the Op-Ed in Tamil and Sinhala.

Homepage photo credit: Shehan Gunasekara

First published in Daily FT on 27 October: http://www.ft.lk/opinion/Sri-Lanka-Vulnerable-groups-pay-the-price-for-militarisation-of-COVID-19-response/14-708073

Oct 9, 2020

An opinion piece by Michelle Yesudas, Legal Adviser, ICJ Asia-Pacific Programme and Rachel Chhoa-Howard, Researcher on Malaysia at Amnesty International.

For decades, Malaysia’s treatment of migrant workers and refugees has wavered between tacit acceptance, neglect, and outright hostility. And the current situation is the lowest point in years.

Refugees and migrant workers have emerged as the government’s favoured excuse for the rise in Covid-19 cases. Most recently, the Prime Minister has attributed the spike in Sabah’s rise in cases to undocumented migrant workers, despite reports of high-profile individuals ignoring quarantine restrictions in droves following state elections.

At a National Security Council meeting at the beginning of this month, the prime minister further stated that to combat the virus, more detention centres that house undocumented migrant workers should be built.

In a recent Information Note on Covid-19, the UN stated that governments have a greater duty to protect people who are in detention. This should be done through “avoiding overcrowding and ensuring hygiene and sanitation in prisons and other detention centres,” among other measures.

Despite this, the practice of arresting, detaining and eventually deporting people alleged to have breached immigration law continues, raising the heightened risk of the disease spreading amongst detainees, as well as spilling over into the general community.

A dangerous shift in government policy

This announcement is just the latest attack on refugee and migrant communities, using the pretext of Covid-19 and weaponised laws to cause untold misery. In recent months, operations by police and immigration officials have seen hundreds of people rounded up and placed in squalid and overcrowded immigration detention facilities, where the risk of contracting Covid-19 is far higher.

Indeed, following raids, immigration detention facilities recorded hundreds of new cases and saw clusters of infections within weeks.

Meanwhile, the coastguard and military pushed away boats of desperate Rohingya people risking their lives to reach the country, or otherwise detained and charged them with immigration offences. Ismail Sabri, Malaysia’s Defence Minister, announced publicly, that Rohingyas have “no status” in the country, despite previous governments being continuously vocal on its support and solidarity with Muslim Rohingyas since 2016.

Home Minister Hamzah Zainudin later added that the government does not recognise the documentation provided by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to these refugees, despite prior agreement that bearers of UNHCR cards would be afforded relative protection.

Malaysian authorities are also cracking down on those who publicly voiced concern and exposed the arbitrary, sweeping laws — on immigration and free speech — that make this toxic state of affairs possible.

In July this year, authorities investigated two Al Jazeera journalists from Australia involved in the making of a documentary shedding light on the appalling treatment of migrant workers and refugees amid the Covid-19 lockdown in Malaysia.

The government detained Rayhan Kabir — a Bangladeshi migrant worker featured in the documentary — for weeks. Since then, police have raided Al Jazeera’s offices in Kuala Lumpur and deported Kabir back to his home country. Other critical voices, including the founder of a refugee support organisation, have also faced harassment from the authorities.

The government has used Covid-19 as an opportunity to radically redefine its position on the acceptance of refugees. It’s most recent crackdown highlights the fact that without proper domestic laws protecting the human rights of migrants and refugees, people live in daily fear of exploitation, arbitrary arrest, detention and other human rights abuses.

An inadequate law at the heart of this inhumane policy

The arrest and detention of migrant workers and refugees emphasizes the problematic provisions of Malaysia’s Immigration Act. Under the Act, senior immigration officers have wide powers of search and arrest, which may be used to harass migrants. It also provides for the imprisonment, often indefinitely, of those in breach of local immigration laws in detention centres.

The Immigration Act has been used to sentence migrants to whipping, which is a cruel, inhuman, and degrading punishment prohibited under international human rights law. Furthermore, broadly-worded provisions of the Immigration Act provide the Director General of Immigration with arbitrary powers to revoke and alter the immigration status of non-citizens, such as the two Al Jazeera journalists whose work permits were not renewed.

In addition, Malaysian authorities have used the Immigration Act to arrest, detain and criminally charge a group of Rohingya refugees that arrived by boat and sentence them with the cruel punishment of whipping.

In June this year, the Langkawi Magistrates Court handed down a decision under Section 6 of the Immigration Act, to punish 27 Rohingya men with whipping and seven months in jail for entering Malaysia without valid documentation. Fortunately, following an outcry, the Alor Setar High Court overturned this decision.

However, there are no safeguards to ensure other Rohingya refugees will not face the same threat, in the future.

Time for change

Clearly, Malaysia’s law and policies do not fulfill its international obligations on migrants and refugees. In fact, they are driving them to despair. Caught between the risk of arrest and unemployment, several people are reported to have committed suicide.

It should not take a global health emergency for the Malaysian government to review its policies on the criminalisation of those who fall foul of the Immigration Act, however there is no better time for the government to do so.

Instead of criminalising people, the government should coordinate across ministries and agencies and work with civil society organisations to amend legislation as well as informal guidelines and policies that fall far below international standards.

Malaysia must also ratify international conventions relating to refugees and migrant workers. And instead of silencing critical voices, authorities should address their well-founded concerns. Only when these measures are in place, will migrants and refugees in Malaysia have the proper protection they deserve.

First published in Malay Mail on 9 October: https://www.malaymail.com/news/what-you-think/2020/10/09/unfettered-powers-fatal-gaps-malaysias-inhumane-crackdown-on-migrants-refug/1911091