Apr 10, 2020 | News

The ICJ today called upon the Myanmar government to ensure that everyone in the country, particularly those from communities affected by conflict, has access to critical information about COVID-19. This call includes putting an immediate end to restrictions on internet access in Rakhine and Chin States.

The ICJ said that there must not be undue restrictions on the right of people to seek and impart such information, in line with international law and standards protecting the right to freedom of expression and information.

“Access to information is absolutely essential for the protection of communities, especially their right to health during the COVID-19 outbreak,” said Frederick Rawski, ICJ Director for Asia and the Pacific. “This is especially true in areas of Myanmar affected by conflict. The wholesale blocking of internet access in Rakhine and Chin States, including access to websites of popular ethnic media outlets, has no justifiable basis in international law and will only serve to undermine efforts to mitigate the spread of the virus.”

On 26 March 2020, the Minister of Transport and Communications stated in a media interview that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the internet shutdown in Rakhine and Chin States would not be lifted until hate speech, misinformation and the conflict with the Arakan Army are addressed. The Minister’s statement appears to defy the UN Secretary-General’s appeal for a global ceasefire as well as the respective statements of members of Myanmar’s diplomatic community and of several ethnic armed organizations, including the Arakan Army, to cease hostilities in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. On 9 April 2020, the UN Special Rapporteur on Myanmar called for the same.

Instead, on 30 March 2020, pursuant to section 77 of the Telecommunications Law, the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MoTC) ordered major telecommunications networks to take down hundreds of websites on the dubious ground of containing misinformation. The MoTC did not disclose the full list of websites ordered to be blocked as well as the factual and legal basis that justified issuing the order. Under Section 77, the MoTC can direct a telecommunications provider to suspend services in the event of an “emergency situation.” It is not clear whether the misinformation relates to COVID-19 or if the pandemic is the pretext for the order.

As of 1 April 2020, media outlets of the Rakhine and Karen ethnic communities were among the websites to which access was blocked from major telecommunications providers. Access to Voice of Myanmar’s website, whose editor-in-chief had faced charges under Myanmar’s Counter-Terrorism Law until 9 April 2020 for publishing an interview with the Arakan Army, was also blocked.

The ICJ has previously expressed concern at the Myanmar Government’s use of the Telecommunications Act to justify an internet shutdown in the context of the conflict in Rakhine State. This practice does not comply with human rights law and standards. The Act itself is fundamentally flawed and must be amended. Among other defects, the Act does not define the scope of an “emergency situation.”

“Keeping these overbroad restrictions in place in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic puts the government in violation of international law. It is also counterproductive to the goal of stopping the spread of the virus and minimizing its impact on the country’s most vulnerable populations,” said Rawski.

Download the statement in Burmese here.

Contact:

Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director, e: Frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

Related work:

Event: ICJ hosts workshop on fair trial rights for Myanmar’s ethnic media

Report: Curtailing the Right to Freedom of Expression and Information in Myanmar

Statement: States must respect and protect rights in fighting COVID-19 misinformation

Apr 8, 2020 | News

The ICJ today warned that Cambodia’s draft Law on National Administration in the State of Emergency (“State of Emergency bill”) violates basic rule of law principles and human rights, and called on the Cambodian government to urgently withdraw or amend the bill in accordance with international human rights law and standards.

Last Friday, government spokesperson Phay Siphan explained that the government needed to bring a State of Emergency law in force to combat the COVID-19 outbreak as “Cambodia is a rule of law country”. The bill is now before the National Assembly and, if passed by the Assembly, will likely be considered in an extraordinary session convened by the Senate. The law will come into force once it has been signed by the King – or in his absence, the acting Head of State, Senate President Say Chhum.

“The Cambodian government has long abused the term “rule of law” to justify bringing into force laws or regulations that are then used to suppress free expression and target critics. This bill is no different,” said Frederick Rawski, ICJ’s Director for Asia and the Pacific.

“Any effective response to the COVID-19 outbreak must not only protect the rights to health and life, but be implemented in accordance with Cambodia’s human rights obligations and basic principles of the rule of law.”

Several serious shortcomings are evident in the State of Emergency bill, including:

- No delineation of a timeline for the imposition of a state of emergency, or criterial process for its termination. The bill provides vaguely that such declaration “may or may not be assigned a time limit. In the event that a state of emergency is declared without a clear time limit, such a state of emergency shall be terminated when the situation allows it” (article 3);

- Expansion of government powers to “ban or restrict” individuals’ “freedom of movement, association or of meetings of people” without any qualification to respect the rights to association and assembly in enforcing such measures (article 5);

- Expansion of government powers to “ban or restrict distribution of information that could scare the public, (cause) unrest, or that can negatively impact national security” and impose “measures to monitor, observe and gather information from all telecommunication mediums, using any means necessary” without any qualification to respect the rights to privacy, freedom of expression and information in enforcing such measures (article 5);

- Overbroad powers for the government to “put in place other measures that are deemed appropriate and necessary in response to the state of emergency” which can allow for significant State overreach (article 5);

- Severe penalties amounting to up to 10 years’ imprisonment of individuals and fines of up to 1 billion Riel (approx. USD 250,000) on legal entities for the vaguely defined offence of “obstructing (State) measures related to the state of emergency” where such obstruction “causes civil unrest or affects national security” (articles 7 to 9);

- No specific indication of which governmental authorities are empowered to take measures under the bill, raising concerns that measures could be taken by authorities or officials in an ad-hoc or arbitrary manner in violation of the principle of legality;

- No indication of sufficient judicial or administrative oversight of measures taken by State officials under the bill – The bill states that the government “must inform on a regular basis the National Assembly and the Senate on the measures it has taken during the state of emergency” and that the National Assembly and the Senate “can request for more necessary information” from the government (article 6) but does not clarify clear oversight procedures for accountability.

“The State of Emergency bill is a cynical ploy to further expand the nearly unconstrained powers of the Hun Sen government, and will no doubt be used to target critical comment on the government’s measures to tackle COVID-19,” said Rawski.

“If passed in its current form, this bill will reinforce the prevailing lack of accountability which defines the government in Cambodia. The government’s time would be better spent developing genuine public health policy responses to the crisis.”

Contact

Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia Pacific Regional Director, e: frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

To download the statement with detailed background information, click here.

See also

ICJ report, ‘Dictating the Internet: Curtailing Free Expression, Opinion and Information Online in Southeast Asia’, December 2019

ICJ report, ‘Achieving Justice for Gross Human Rights Violations in Cambodia: Baseline Study’, October 2017

ICJ, ‘Cambodia: continued misuse of laws to unduly restrict human rights (UN statement)’, 26 September 2018

ICJ, ‘Misuse of law will do long-term damage to Cambodia’, 26 July 2018

ICJ, ‘Cambodia: deteriorating situation for human rights and rule of law (UN statement)’, 27 June 2018

ICJ, ‘Cambodia human rights crisis: the ICJ sends letter to UN Secretary General’, 23 October 2017

Apr 6, 2020 | News

ICJ has joined other NGOs in welcoming steps taken by Indian authorities to decongest prisons in an effort to contain the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). The Government should release all unjustly detained prisoners as a matter of priority.

The joint statement read as follows:

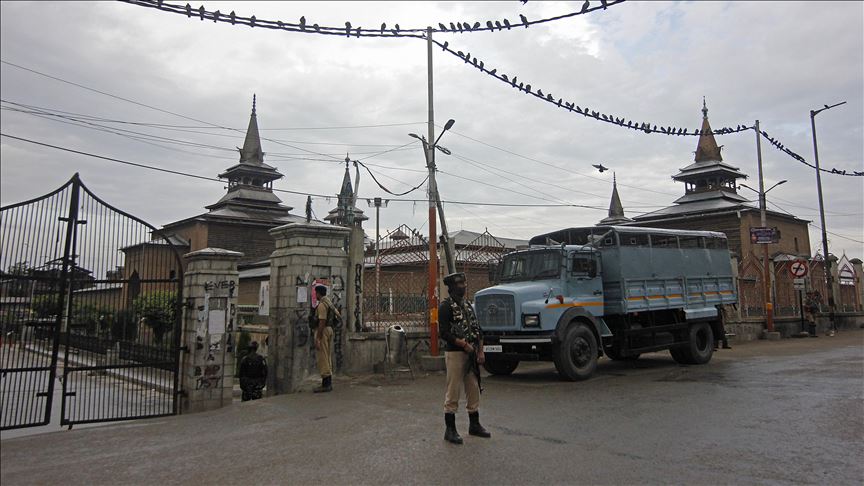

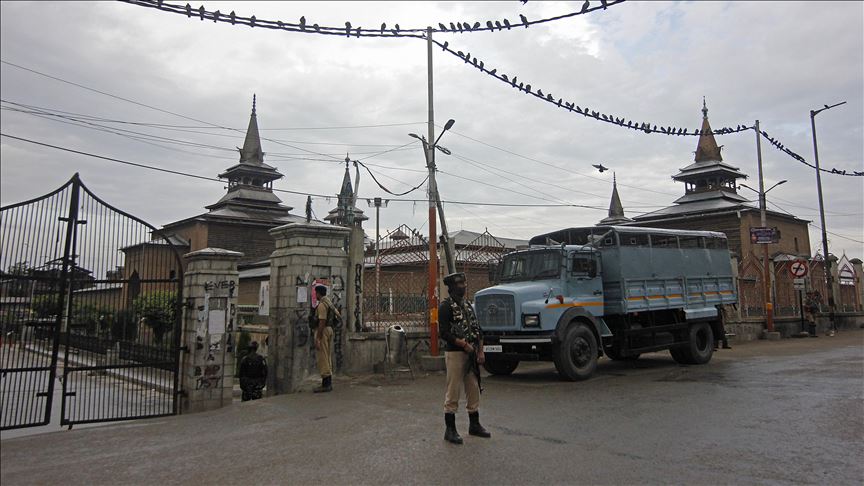

The fate of hundreds of arbitrarily detained Kashmiri prisoners hangs in the balance as the number of confirmed cases of coronavirus in India passes the 4,000 mark and many more are likely to remain undetected or unreported.

Inmates and prison staff, who live in confined spaces and in close proximity with others, remain extremely vulnerable to COVID-19. While the rest of the country is instructed to respect social isolation and hygiene rules, basic measures like hand washing – let alone physical distancing – are just not possible for prisoners.

Under international law, India has an obligation to ensure the physical and mental health and well-being of inmates. However, with an occupancy rate of over 117%, precarious hygienic conditions and inadequate health services, the overcrowded Indian prisons constitute the perfect environment for the spread of coronavirus.

In a bid to contain the spread of the disease among inmates and prison staff, the Supreme Court asked state governments on 23 March 2020 to take steps to decongest the country’s prison system by considering granting parole to those convicted or charged with offenses carrying jail terms of up to seven years.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet also called on governments to “examine ways to release those particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, among them older detainees and those who are sick, as well as low-risk offenders.”

Various state governments in India have now begun releasing detainees. However, there is a concern that hundreds of Kashmiri youth, journalists, political leaders, human right defenders and others arbitrarily arrested in the course of 2019, including following the repeal of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution on 5 August 2019, will not be among those benefiting from the measure. Article 370 provided special status to Jammu & Kashmir.

Human rights groups and UN experts have repeatedly called for the release as a matter of priority of “those detained without sufficient legal basis, including political prisoners and others detained simply for expressing critical or dissenting views.”

Last month, the Ministry of Home Affairs revealed that 7,357 persons had been arrested in Jammu & Kashmir since 5 August 2019. While the majority have since been released, hundreds are still detained under sections 107 and 151 of the Criminal Procedure Code, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), and the Public Security Act (PSA), a controversial law which allows the administrative detention of any individual for up to two years without charge or trial. Reportedly, many of those still detained are minors.

Many of those detained were transferred to prisons all across India, thousands of kilometers away from their homes, hampering their lawyers’ and relatives’ ability to visit them. Some of the families, often too poor to afford to travel, have been left with nothing but concerns over the physical and psychological well-being of their loved ones.

Mr. Miyan Abdul Qayoom, a human rights lawyer and President of the Jammu & Kashmir High Court Bar Association, was also cut off from his family and lawyer. Detained since 4 August 2019 in India’s Uttar Pradesh State, he was transferred to Tihar jail in New Delhi following a deterioration of his health. Mr. Qayoom, 70, suffers from diabetes, double vessel heart disease, and kidney problems.

Mr. Ghulam Mohammed Bhat was also transferred to a jail in Uttar Pradesh. In December 2019, he died thousands of kilometers away from his home at the age of 65 due to lack of medical care.

With the entire country in a lockdown and a ban on prison visits for the duration of the outbreak imposed, inmates are more isolated from the outside world than ever. In such a situation, prison authorities must ensure that alternative means of communication, such as videoconferencing, phone calls and emails, are allowed. However, this has not often been the case. Especially in Jammu & Kashmir, where full internet services are yet to be restored after a communication blackout imposed on the population on 5 August 2019, contacts between inmates and the outside world are even more limited.

- Amnesty International India

- Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

- CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

- International Commissions of Jurists (ICJ)

- International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

- World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

To download the statement with detailed information and key recommendations, click here.

Apr 6, 2020

Today, the ICJ submitted an open letter to the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister and acting Minister of Health, Minister of Public Security and Minister of Justice of Vietnam, expressing concerns about detainees whose physical integrity and well being are believed to be at risk.

This is because they have not been provided with adequate access to healthcare and medical treatment in prison.

The ICJ also called on the Vietnamese authorities to respect, protect and fulfill its obligations to ensure humane treatment and provide equal right of access to healthcare and health services to all prisoners and detained individuals, in their measures to combat the COVID-19 outbreak; and to release detainees particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 crisis, including older detainees and those who are sick or suffering from pre-existing medical conditions.

In its letter, the ICJ raised concerns about the condition of 21 detainees who have allegedly not been provided adequate access to healthcare and medical treatment. The detainees are adherents of the An Dan Dai Dao, a Buddhist religious organization which has been the target of official persecution, raising concerns that their prosecution and their mistreatment in detention may be linked to their religious affiliation.

The ICJ urgently requested Vietnamese authorities to take immediate steps to:

- Ensure that the responsible authorities provide the detained individuals with access to adequate, prompt and continuous healthcare and medical attention, in line with Vietnam’s Constitution, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) – both to which Vietnam is a State party. Such provision should also be in accordance with the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (“Nelson Mandela Rules”), which should be fully implemented;

- Ensure that the responsible authorities meet the State’s obligations to provide equal right of access to healthcare, health facilities, goods and services to all prisoners and detained individuals;

- Conduct medical examinations and risk assessments of all persons held in detention, and release those particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 virus, including older detainees and those who are sick or suffering from pre-existing medical conditions, including the 21 individuals named in the letter;

- Ensure that detainees, including the 21 individuals named in the letter, are not subjected to torture or other ill-treatment and that their rights to humane treatment, dignity and life are protected in accordance with articles 7 and 10 of the ICCPR and the UN Convention against Torture (UNCAT), to which Vietnam is a State party.

To download the open letter, click here.

To download the annex, click here.

To download the full statement with background information, click here.

Contact

Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia Pacific Regional Director, e: frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

Apr 6, 2020

An opinion piece by Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser, Global Redress and Accountability

In New Zealand, swimming at the beach is prohibited, an activity so entrenched in the Kiwi psyche that for many it is like being asked to go without oxygen.

The Government has asked everyone to “unite against Covid-19” by living under the severest restrictions on fundamental freedoms the country has ever known. On 25 March, a one-week State of Emergency was declared, which was renewed for another seven days on 31 March.

New Zealand is also experiencing a “lockdown” under a Government-imposed “Covid-19 Alert System”, which means that, under the current Alert Level 4, nearly everyone must stay at home for at least four weeks unless they are purchasing groceries, medical supplies or enjoying exercise locally, among other restrictions.

This situation has taken us into unchartered territory and Kiwis should monitor the actions of our Government carefully.

Restrictions are being enforced by the police, who now enjoy extensive, broadly-worded, powers under the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act and the Health Act.

And the police have been active, including by setting up checkpoints to screen peoples’ movements, asking Kiwis to report on their neighbours who break the rules, and requesting people in non-managed self-isolation give consent to the police to track their movements using their cellular devices.

The Government’s response to Covid-19 appears to have the general support of most people.

Kiwis have good reason trust their Government, with New Zealand’s strong track record of upholding human rights and the rule of law.

And it should be commended for its swift implementation of a range of special actions taken to alleviate peoples’ suffering at this time, including the most vulnerable, such as by providing a wage subsidy scheme, leave and self-isolation support, business cash flow and tax measures, a mortgage repayment holiday scheme and a business finance guarantee scheme.

Establishing a bi-partisan Epidemic Response Committee to oversee the Government’s response was also a positive step, and should serve as a model to other states.

That said, we should not be complacent about the magnitude of what we are being asked to endure, and what it already means for the “Kiwi way of life”, our communities and the nation.

Lessons learned from around the world where living under limitations on rights and states of emergency has become a way of life for many (such as in Thailand where I live and work), include that without constant scrutiny, restrictions put in place to respond to an emergency can be abused and sometimes linger long after they are required, assuming they were ever required in the first place.

Another, global, example is how in the post-September 11 context, different limitations which were put in place to combat the specific threat of terrorism – including enhanced powers of state surveillance – remain in place today, altering the trajectory of whole societies around the world.

So, what does monitoring our Government’s response to Covid-19 mean for New Zealand and what can we use as a yardstick?

It is not widely known that an international human rights legal framework exists which applies to precisely this situation, and that it is legally binding on New Zealand.

The Government – including the police – cannot simply do whatever it wants to combat the pandemic, even in good faith.

Rather, the framework requires New Zealand to place human rights and the rule of law at the forefront of its response.

Among other things, the Government must ensure that each and every restriction on our rights and freedoms has a clear legal basis; is described in specific terms so that people know how their rights are being limited, under which law, and precisely what they are (and are not) permitted to do; and is subject to the review of the courts, if necessary.

In combating Covid-19, all states, including New Zealand, are confronted with the challenge of ensuring that the whole protective fabric of human rights (civil, political, economic, social and cultural) and the rule of law is applied coherently and consistently.

New Zealand has a duty to respect, protect and fulfil a cluster of rights, including the right to life and the right to health.

These duties have a range of sources in national and international law, including under treaties to which New Zealand is a State Party, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

For example, Article 12 of the ICESCR – which deals with the right to health – recognises New Zealand’s duty to respect, protect and fulfil “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” and the obligation to take effective steps for the “prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases.”

At the same time, New Zealand has a duty to respect, protect and fulfil another range of interrelated and interdependent rights including the rights to free movement, expression, assembly and association found in our domestic law (such as the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act) and the ICCPR.

Article 12 of the ICCPR states that “Everyone lawfully within the territory of a State shall, within that territory, have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose his residence.”

This is the Article that protects, for example, our right to travel between cities or go for a swim at the beach.

Subsection 3 allows certain restrictions on the right to movement but only in limited circumstances, including to protect public health: “The above-mentioned rights shall not be subject to any restrictions except those which are provided by law, are necessary to protect national security, public order (ordre public), public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others, and are consistent with the other rights recognized in the present Covenant.”

And by declaring a State of Emergency, New Zealand has entered into another, quite specific, legal territory that has its own framework for dealing with public emergencies, should it seek to derogate (suspend or restrict obligations in certain emergency situations) from its obligations under the ICCPR, which it does not appear to have done so far.

Whether through normal limitation or emergency derogation, there are certain conditions to restricting rights that must always be observed under international human rights law and standards.

The Siracusa Principles and the jurisprudence of the UN treaty bodies (tasked with monitoring the implementation of the core international human rights treaties) set out what these requirements mean in practice.

In particular, any restrictions should, at a minimum, be:

• provided for and carried out in accordance with the law;

• directed toward a legitimate objective, as provided under the ICCPR (in this case public health);

• strictly necessary in a democratic society to achieve the objective;

• the least intrusive and restrictive available to reach the objective;

• based on scientific evidence and be neither arbitrary nor discriminatory in application; and

• of limited duration, respectful of human dignity, and subject to review.

While we should, of course, obey the current range of restrictions, we should also be aware of the Government’s obligations and our rights.

Government accountability, transparency and the rule of law – always necessary – is vital in these extraordinary times.

For example, we should welcome how initial confusion about the precise scope of restrictions, their legal basis and how they are being policed is now being addressed, including through a new, detailed, Health Act Order, and release of the Police’s Operational Policing Guidelines, both issued after questions were raised before the Epidemic Response Committee on Friday.

As the Covid-19 pandemic continues to rage around the world, many governments are struggling with an appropriate reaction.

New Zealand should continue to establish itself as a global leader on what a response grounded in human rights and the rule of law looks like.

To download the Op-Ed, click here.

This article was first published on Newsroom, available at: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/pro/2020/04/06/1117304/our-unprecedented-lockdown-should-be-carefully-monitored