The ICJ expressed disappointment over the decision made today by the Malaysian Federal Court to refer human rights defender Lena Hendry for trial, after dismissing the constitutional challenge on section 6(1)(b) of the Film Censorship Act 2002.

The ICJ said this provision is being applied in a manner inconsistent with the right to freedom of expression, which includes the right to seek and impart information of all kinds.

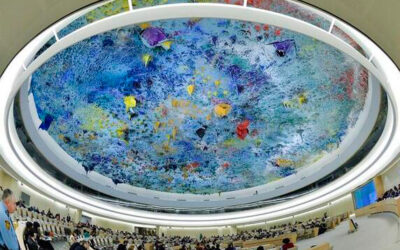

“The decision by the Federal Court is incompatible with the commitment to the rule of law and respect for human rights which was expressed by Malaysia during its last Universal Periodic Review at the UN Human Rights Council in 2013,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Regional Director for Asia and the Pacific.

“Lena Hendry is clearly a human rights defender and Malaysia has the special duty not only to respect her right to freedom of expression, but to protect her exercise of this right through the exposure of human rights violations in Sri Lanka,” he added.

The constitutional challenge was brought by the lawyers of Lena Hendry who was charged under section 6(1)(b) of the Film Censorship Act 2002 for screening the film “No Fire Zone: the Killing Fields of Sri Lanka” on 3 July 2013.

Authorities allege that she violated section 6(1)(b) of the law for showing a film that had not been approved by the Board of Censors.

The lawyers of Lena Hendry are now preparing for the trial before the Magistrate’s Court.

The ICJ calls on the Government of Malaysia to drop all charges against Lena Hendry and to undertake steps to make its laws consistent with the country’s obligations and commitments under international law.

Background:

Section 6(1)(b) of the Film Censorship Act 2002 states that “No person shall circulate, exhibit, distribute, display, manufacture, produce, sell, or hire any film or film publicity material, which has not been approved by the Board [of Censors].”

On 14 September 2015, the Federal Court of Malaysia dismissed the constitutional challenge on Section 6(1)(b) of the Film Censorship Act 2002. The question posed to the Federal Court was: “Whether section 6(1)(b) of the Film Censorship Act 2002 read together with section 6(2)(a) violates Article 10 read together with Article 8(1) of the Federal Constitution and therefore should be struck down and void for unconstitutionality.”

The Federal Court answered the question in the negative and ordered that the case be sent back to the High Court. The High Court, in turn, will transfer the matter back to the Magistrate’s court for trial. The Magistrate’s Court is where the matter initially originated.

If convicted, under section 6(2)(a) Lena Hendry could be fined up to RM30,000 (approximately US$6,900) and/or sentenced to up to three years imprisonment.

The right to freedom of expression is guaranteed in the Federal Constitution of Malaysia under Section 10(1)(a), which states that “every citizen has the right to freedom of speech and expression.”

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders also affirm the duty of all states to respect and facilitate freedom of expression, particularly as regards information or opinions about human rights.

Contact:

Emerlynne Gil, Senior International Legal Adviser of ICJ for Southeast Asia, t: +66 840923575 ; e: emerlynne.gil(a)icj.org