Aug 29, 2013 | News

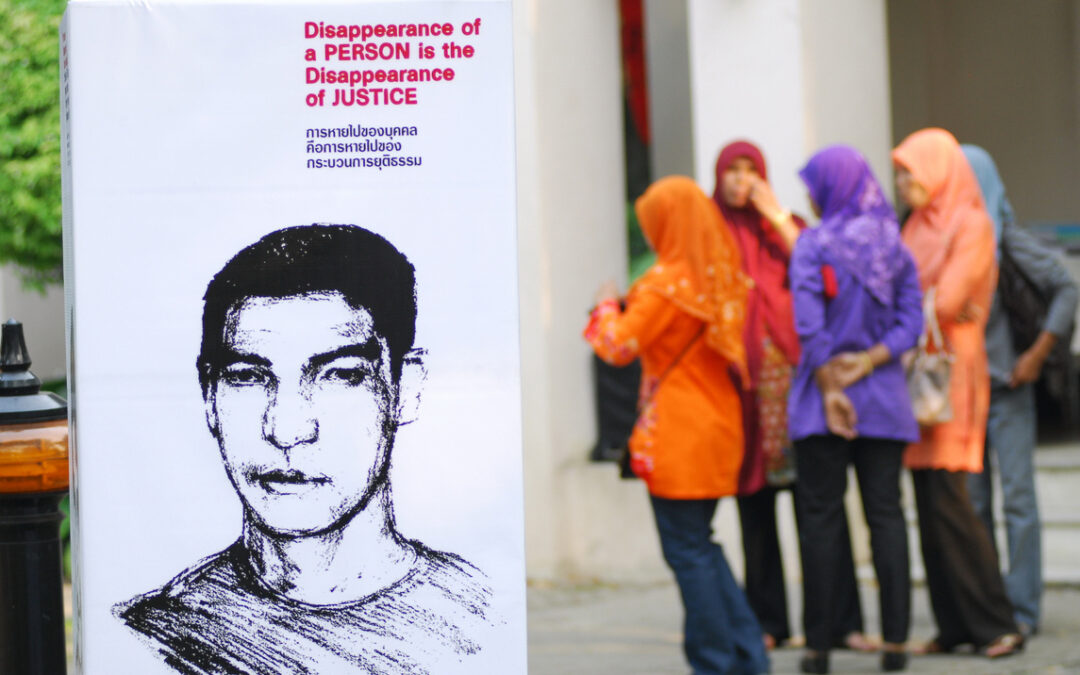

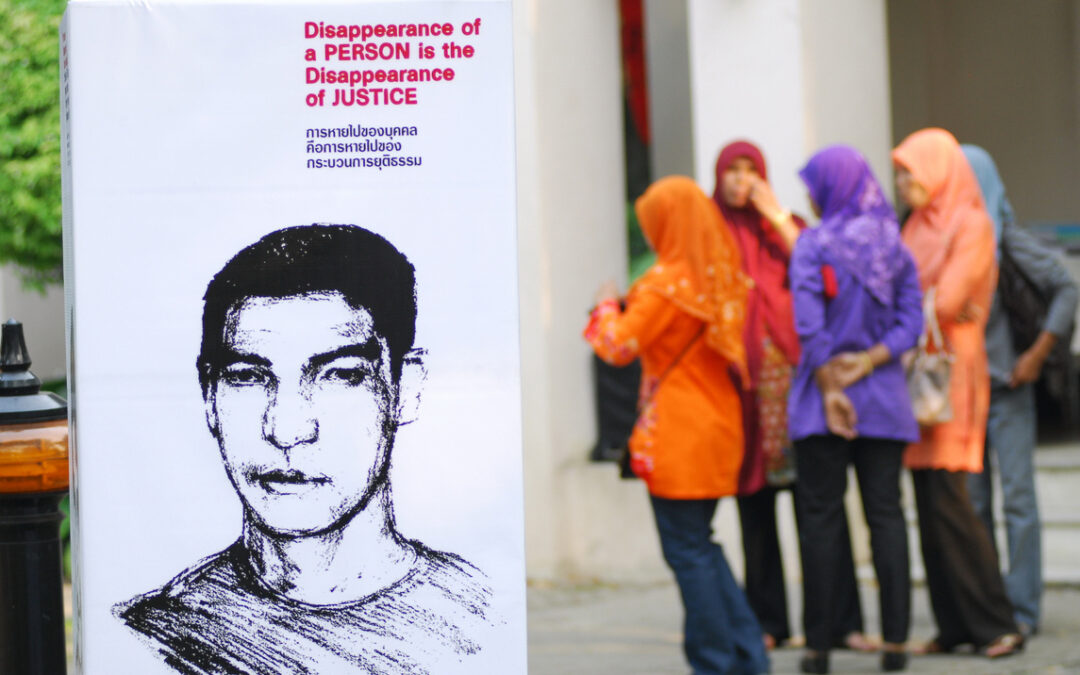

The Pakistani government should affirm its commitment to end enforced disappearances by ratifying the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

The call by the ICJ and Human Rights Watch comes on the eve of the third annual United Nations International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances (30 August 2013).

“Ratifying the Convention against Disappearances is a key test for Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s new government,” said Ali Dayan Hasan, Pakistan director at Human Rights Watch. “The government would send a clear political message that it’s serious about ending ‘disappearances’. And it would show its commitment to ensuring justice for serious human rights violations.”

Pakistan’s participation in the United States-led “war on terror” since 2001 has resulted in hundreds and perhaps thousands of individuals being “disappeared.”

In addition to those arbitrarily detained in counter-terrorism operations, journalists, human rights activists and alleged members of separatist and nationalist groups, particularly in Balochistan province, have been and continue to be forcibly disappeared.

“Pakistan’s failure to hold even a single perpetrator of enforced disappearances to account perpetuates the culture of impunity in Pakistan,” said Sam Zarifi, Asia-Pacific Regional Director of ICJ. “The prevalence of gross violations of human rights in the country today is partly a legacy of this impunity.”

Despite repeated denials by Pakistan’s security agencies, the Supreme Court of Pakistan has acknowledged and human rights groups have documented evidence of the involvement of intelligence and security agencies in enforced disappearances.

In July, Pakistan’s attorney general admitted that more than 500 “disappeared” persons are in security agency custody.

“In Balochistan and beyond, Pakistani security forces have forcibly disappeared, tortured, and unlawfully killed people in the name of counter-terrorism,” Hasan added. “Pakistan has a responsibility to arrest and prosecute militants acting outside the law, but abuses against suspects cannot be explained away as a way to end terrorism.”

“All disappeared persons must be released or, if charged with recognizable crimes, brought without further delay before a court to see if their continuing detention is legal,” Zarifi concluded. “The government should also fully investigate and prosecute those who are responsible for ordering, participating or carrying out enforced disappearances.”

The UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances in its 2012 report on Pakistan found that the country’s anti-terrorism laws, in particular the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997, and the FATA/PATA Action (in aid of civil powers) Regulations 2011, allowed arbitrary deprivation of liberty, which has enabled enforced disappearances.

Under international law, a state commits an enforced disappearance when its agents take a person into custody and then deny holding the person, or conceal or fail to disclose the person’s whereabouts.

Family members and legal representatives are not informed of the person’s whereabouts, well-being, or legal status.

“Disappeared” people are often at high risk of torture, a risk even greater when they are detained outside of formal detention facilities such as prisons and police stations.

An enforced disappearance removes an individual from the protection of the law, leaving the individual without protection from theirs.

It violates many of the rights guaranteed under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Pakistan ratified in 2010.

The UN General Assembly has repeatedly described enforced disappearance as “an offence to human dignity” and “a grave and flagrant violation” of international human rights law.

The ICJ and Human Rights Watch called on the Pakistani government to carry out a full review of security-related legislation and ensure that all laws conform to Pakistan’s international law obligations to prevent such violations.

Contact:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director, t: +66 807 819 002 (mobile); email: sam.zarifi(at)icj.org

Read also:

Justice for Pakistan’s “disappeared”

Apr 23, 2013 | Advocacy, Cases, Legal submissions

The ICJ and Amnesty International presented a third party intervention in the case Abu Zubaydah v. Lithuania before the European Court of Human Rights.

The ICJ and Amnesty International presented a third party intervention in the case Abu Zubaydah v. Lithuania before the European Court of Human Rights.

In the third party intervention, the ICJ and AI outlined developments on the knowledge imputable to Contracting Parties at relevant times; on the obligations attached to principle of non-refoulement; on the duty to investigate credible allegations of human rights violations and other procedural obligations; and on the human rights violations that detainees previously held in the USA’s secret detention and rendition programmes are currently enduring.

Abu_Zubaydah_v_Lithuania-ICJAIJointSubmission-ECtHR-final (download the third party intervention)

Apr 8, 2013 | News

The ICJ today expressed its deep concern at the decision of the President of the Republic of Italy to pardon Colonel Joseph L. Romano III, following his conviction by an Italian court for complicity in the rendition of Osama Moustafa Hassan Nasr, also known as Abu Omar (photo).

The ICJ today expressed its deep concern at the decision of the President of the Republic of Italy to pardon Colonel Joseph L. Romano III, following his conviction by an Italian court for complicity in the rendition of Osama Moustafa Hassan Nasr, also known as Abu Omar (photo).

“This pardon deals a serious blow to the rule of law and to accountability for CIA renditions and secret detentions, a system which involved torture, enforced disappearances, arbitrary and secret detention and other serious crimes under international law,” said Massimo Frigo, Legal Adviser with the ICJ Europe Programme. “Italy stood honourably as the only country where an effective prosecution had been brought against CIA and Italian agents responsible for crimes under international law committed through the CIA rendition programme. This pardon deletes, in a single stroke of the pen, years of relentless efforts of prosecutors, investigators and lawyers to assure accountability for these crimes under international law.”

The ICJ emphasized that the pardon granted by the Italian President of the Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, in his last weeks of office, defeats the efforts of the judiciary to uphold the State’s international law obligations to investigate, prosecute and bring to justice those responsible for gross violations of human rights.

“By nullifying the effects of years of efforts of the Italian judicial system, this pardon seriously undermines Italy’s action against impunity and weakens the very foundations of the rule of law,” Frigo added. “The fact that the President of the Republic justified this action by raising the “peculiarity of the historical moment” of 9/11, thus suggesting that a kind of state of exception for the rule of law could have existed, is an unacceptable position under international law.”

The ICJ deeply regrets this decision of the President of the Republic to use his prerogative of pardon to prevent accountability for such an egregious violation of the rule of law in name of US-Italian diplomatic relations.

The ICJ condemns this pardon and stresses that it must not constitute a precedent and that other convictions in this case must not be nullified by pardons or amnesties. All European countries must uphold their duty fight against impunity for gross violations of human rights.

Any further circumvention of accountability for perpetrators of renditions or other gross human rights violations would only extend the cloak of impunity over the rule of law in Europe.

Contact:

Massimo Frigo, Legal Adviser, ICJ Europe Programme, massimo.frigo(a)icj.org

PR-Italy-RenditionPardon-2013-eng (english version)

PR-Italy-RenditionPardon-2013-ita (italian version)

Mar 22, 2013 | Feature articles, News

The inclusion of an amnesty provision, which could cover the worst possible crimes, in Nepal’s new Truth, Reconciliation and Disappearance Ordinance, will make it impossible for thousands of victims of gross human rights violations to obtain justice, ICJ and other right groups said today.

The Asian Centre for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, the International Commission of Jurists and TRIAL pointed to fundamental flaws in Nepal’s new law, passed by President Ram Baran Yadav on March 14, 2013.

“The new ordinance leaves open the door to amnesties for persons implicated in gross human rights violations and crimes under international law,” said Ben Schonveld, ICJ’s South Asia director in Kathmandu. “Amnesties for serious rights violations are prohibited under international law and betray the victims, who would be denied justice in the name of political expediency.”

At least 13,000 people were killed and over 1,300 subjected to enforced disappearance in Nepal’s decade-long conflict between government forces and Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) combatants.

The fighting ended with the signing of the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, consolidating a series of commitments to human rights.

However, the government has yet to take steps to ensure that those responsible for crimes under international law during the fighting are identified and prosecuted.

International and local human rights groups have consistently decried the government’s efforts to side-step promises of justice and accountability, represented most recently by this new ordinance.

The revised ordinance calls for the formation of a high-level commission to investigate serious human rights violations committed during Nepal’s armed conflict from 1996 to 2006.

It grants the commission discretion to recommend amnesty for a perpetrator if the grounds for that determination are deemed reasonable.

The government then decides whether to grant an amnesty. There is no definition of what is reasonable.

Confusion over scope of amnesty provision

The ordinance states that “serious crimes,” including rape, cannot be recommended for an amnesty, but it does not define what other “serious crimes” are not subject to an amnesty.

Gross violations of human rights, such as extrajudicial killing, torture and enforced disappearance, are not mentioned.

Torture and enforced disappearance are not specific crimes under Nepali domestic criminal law.

The organizations expressed concern that the commission’s powers to recommend prosecution may mean little without crimes being adequately defined in law.

The final decision on whether to prosecute can only be made by the attorney general, a political appointee of the government, instead of an independent entity.

Human Rights Watch, ICJ and TRIAL have previously documented the systematic failures of the Nepali criminal law system to address serious human rights violations.

“Nepal has had years to investigate some 1,300 suspected enforced disappearances during the conflict and thousands of other human rights violations, but it has failed to deliver any credible or effective investigations,” said TRIAL Director Philip Grant in Geneva. “The provisions on prosecution contained in this ordinance don’t appear to be strong enough to overcome Nepal’s entrenched practices of safeguarding impunity by withdrawing cases or failing to pursue credible allegations. It does not leave victims with much faith that the commission will fulfill its mandate to end impunity.”

Call for review and consultation

The organizations called upon the government to establish a mechanism to review and amend the legislation in consultation with victims of human rights abuses and representatives of civil society.

“This ordinance was signed by the prime minister and president in record time without any consultation with conflict victims and civil society,” Schonveld added. “If the government had carried out proper consultations, the result would have been different, and we wouldn’t have an ordinance that entrenches impunity.”

The rights organizations also expressed concern about the ordinance’s heavy emphasis on reconciliation at the possible expense of justice for victims.

The ordinance cedes authority to the commission to implement “inter-personal reconciliation” between victim and perpetrator, even if neither the victim nor the perpetrator requests it, which could result in pressure being placed on a victim to give up any claims against a perpetrator.

Although the ordinance mentions the need for victim and witness protection, there are no specific safeguards to ensure the safety and security of victims who become involved in reconciliation processes.

Violation of international obligation for political expediency

Under international law, Nepal is obliged to take effective measures to protect human rights, including the right to life and freedom from torture and other ill-treatment.

Where a violation occurs, Nepali authorities must investigate, institute criminal proceedings, and ensure victims are afforded access to effective remedy and reparations.

“The passage of this ordinance is just the latest example of the Nepali government’s cynical willingness to trade meaningful justice and accountability for political expediency,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The government is kidding itself if it thinks it can ignore the voices of Nepal’s thousands of victims of human rights abuses. Nepal needs meaningful government initiatives to address its human rights problems, not the veneer of justice that this flawed ordinance represents.”

Contact:

In Kathmandu, for ICJ, Ben Schonveld: ben.schonveld(at)icj.org

In Bangkok, for ICJ, Sheila Varadan: +66-857-200-723; sheila.varadan(at)icj.org

Mar 18, 2013 | Advocacy, Cases, Legal submissions

The ICJ and Amnesty International presented a third party intervention in the case Al Nashiri v Romania before the European Court of Human Rights.

The ICJ and Amnesty International presented a third party intervention in the case Al Nashiri v Romania before the European Court of Human Rights.

In the third party intervention, the ICJ and AI outlined developments on the prohibition of arbitrary deprivation of liberty as a rule of customary international law; on the knowledge imputable to Contracting Parties at relevant times; on the duty to investigate credible allegations of human rights violations and the right to truth; and on the evidential approach to enforced disappearances.

AlNashiri_v_Romania-ICJAIJointSubmission-ECtHR-final (download the third party intervention