Mar 22, 2013 | Feature articles, News

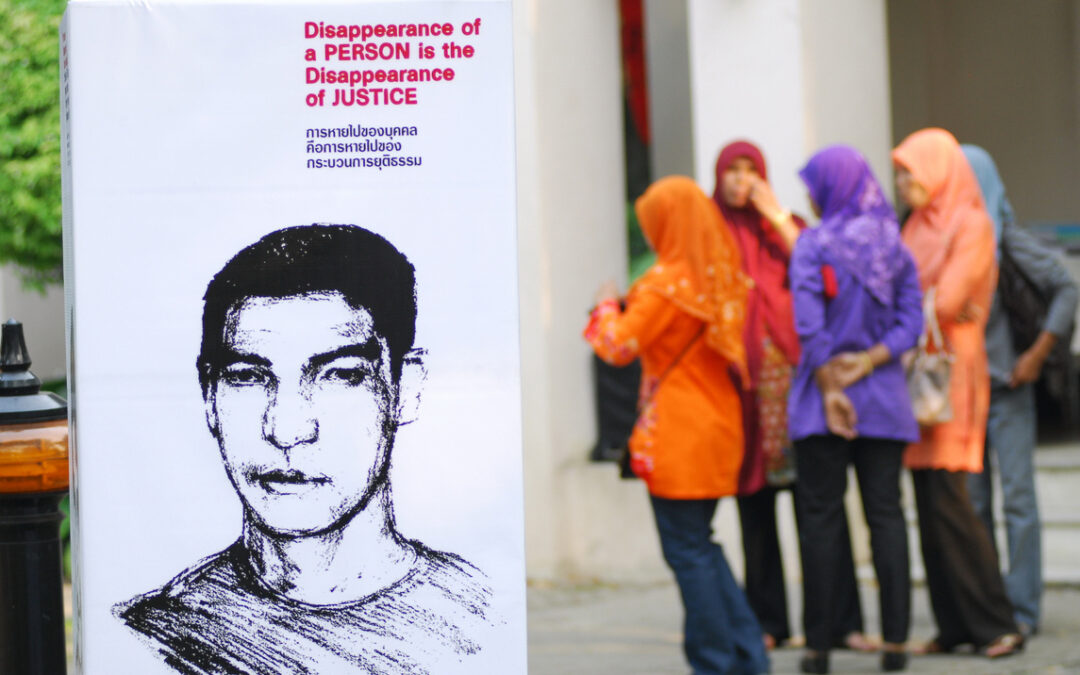

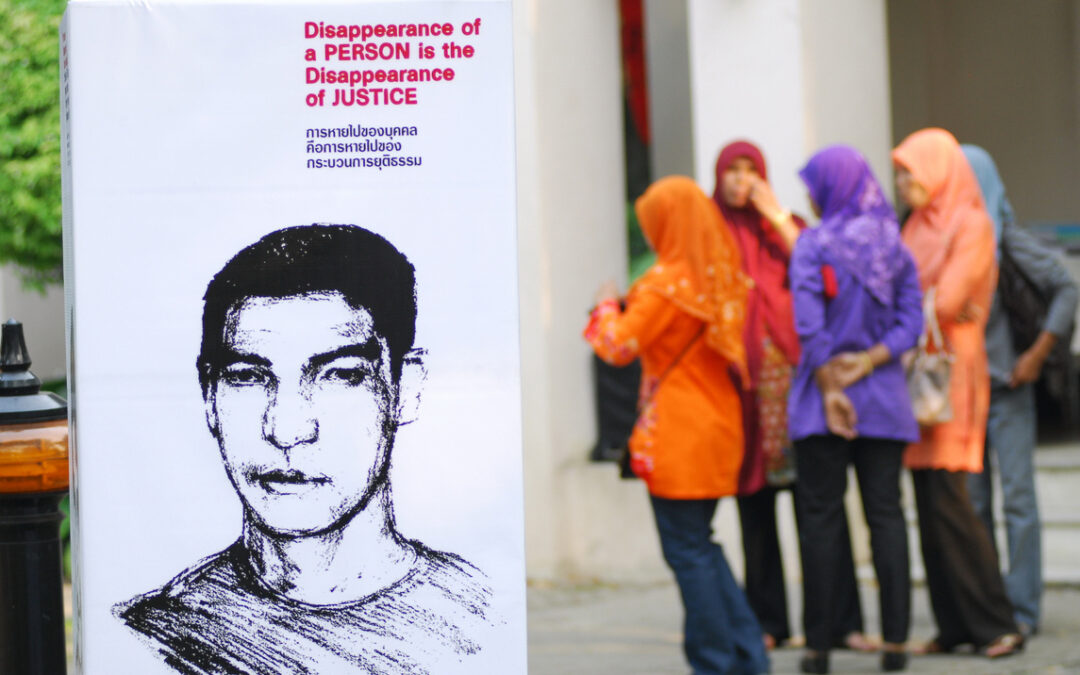

The inclusion of an amnesty provision, which could cover the worst possible crimes, in Nepal’s new Truth, Reconciliation and Disappearance Ordinance, will make it impossible for thousands of victims of gross human rights violations to obtain justice, ICJ and other right groups said today.

The Asian Centre for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, the International Commission of Jurists and TRIAL pointed to fundamental flaws in Nepal’s new law, passed by President Ram Baran Yadav on March 14, 2013.

“The new ordinance leaves open the door to amnesties for persons implicated in gross human rights violations and crimes under international law,” said Ben Schonveld, ICJ’s South Asia director in Kathmandu. “Amnesties for serious rights violations are prohibited under international law and betray the victims, who would be denied justice in the name of political expediency.”

At least 13,000 people were killed and over 1,300 subjected to enforced disappearance in Nepal’s decade-long conflict between government forces and Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) combatants.

The fighting ended with the signing of the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, consolidating a series of commitments to human rights.

However, the government has yet to take steps to ensure that those responsible for crimes under international law during the fighting are identified and prosecuted.

International and local human rights groups have consistently decried the government’s efforts to side-step promises of justice and accountability, represented most recently by this new ordinance.

The revised ordinance calls for the formation of a high-level commission to investigate serious human rights violations committed during Nepal’s armed conflict from 1996 to 2006.

It grants the commission discretion to recommend amnesty for a perpetrator if the grounds for that determination are deemed reasonable.

The government then decides whether to grant an amnesty. There is no definition of what is reasonable.

Confusion over scope of amnesty provision

The ordinance states that “serious crimes,” including rape, cannot be recommended for an amnesty, but it does not define what other “serious crimes” are not subject to an amnesty.

Gross violations of human rights, such as extrajudicial killing, torture and enforced disappearance, are not mentioned.

Torture and enforced disappearance are not specific crimes under Nepali domestic criminal law.

The organizations expressed concern that the commission’s powers to recommend prosecution may mean little without crimes being adequately defined in law.

The final decision on whether to prosecute can only be made by the attorney general, a political appointee of the government, instead of an independent entity.

Human Rights Watch, ICJ and TRIAL have previously documented the systematic failures of the Nepali criminal law system to address serious human rights violations.

“Nepal has had years to investigate some 1,300 suspected enforced disappearances during the conflict and thousands of other human rights violations, but it has failed to deliver any credible or effective investigations,” said TRIAL Director Philip Grant in Geneva. “The provisions on prosecution contained in this ordinance don’t appear to be strong enough to overcome Nepal’s entrenched practices of safeguarding impunity by withdrawing cases or failing to pursue credible allegations. It does not leave victims with much faith that the commission will fulfill its mandate to end impunity.”

Call for review and consultation

The organizations called upon the government to establish a mechanism to review and amend the legislation in consultation with victims of human rights abuses and representatives of civil society.

“This ordinance was signed by the prime minister and president in record time without any consultation with conflict victims and civil society,” Schonveld added. “If the government had carried out proper consultations, the result would have been different, and we wouldn’t have an ordinance that entrenches impunity.”

The rights organizations also expressed concern about the ordinance’s heavy emphasis on reconciliation at the possible expense of justice for victims.

The ordinance cedes authority to the commission to implement “inter-personal reconciliation” between victim and perpetrator, even if neither the victim nor the perpetrator requests it, which could result in pressure being placed on a victim to give up any claims against a perpetrator.

Although the ordinance mentions the need for victim and witness protection, there are no specific safeguards to ensure the safety and security of victims who become involved in reconciliation processes.

Violation of international obligation for political expediency

Under international law, Nepal is obliged to take effective measures to protect human rights, including the right to life and freedom from torture and other ill-treatment.

Where a violation occurs, Nepali authorities must investigate, institute criminal proceedings, and ensure victims are afforded access to effective remedy and reparations.

“The passage of this ordinance is just the latest example of the Nepali government’s cynical willingness to trade meaningful justice and accountability for political expediency,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The government is kidding itself if it thinks it can ignore the voices of Nepal’s thousands of victims of human rights abuses. Nepal needs meaningful government initiatives to address its human rights problems, not the veneer of justice that this flawed ordinance represents.”

Contact:

In Kathmandu, for ICJ, Ben Schonveld: ben.schonveld(at)icj.org

In Bangkok, for ICJ, Sheila Varadan: +66-857-200-723; sheila.varadan(at)icj.org

Mar 21, 2013 | News

A resolution adopted today by the UN Human Rights Council highlights the Sri Lankan Government’s ongoing failure to provide accountability for serious violations of human rights and the laws of war, the ICJ said.

“The ICJ welcomes this resolution as it underscores the international community’s continuing concern about the horrific atrocities committed by all sides to the Sri Lankan conflict,” said Alex Conte, Director of ICJ’s International Law and Protection Programmes. “The UN, as well as the Commonwealth and other international organizations interested in helping the Sri Lankan people, should now press and assist the Sri Lankan Government to show tangible implementation of their oft-repeated promises.”

Twenty-five States supported the resolution, following from a similar resolution adopted by the Council on Sri Lanka last year.

The resolution reiterates the need for the Sri Lankan Government to demonstrate tangible steps to ensure accountability for violations of human rights and the laws of war, especially during the final months of the three-decade long conflict in 2009.

In particular, the resolution calls on the Sri Lankan Government to implement the recommendations of its own Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC).

The LLRC was widely criticized by Sri Lankan civil society as well as international observers as falling short of international standards of providing accountability.

“Sri Lanka has a long history of promising justice but delivering impunity, and the LLRC is only the most recent example of that. With this resolution, the international community shows it wants to see concrete action,” Conte added. “Not only has the Sri Lankan Government not addressed the violations of the past, but there are strong indications that the rule of law has significantly deteriorated.”

The resolution notes with concern the ongoing reports of human rights violations being committed with impunity in Sri Lanka, including enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings and torture.

In October 2012, the ICJ released a 150-page report Authority without Accountability: The Crisis of Impunity in Sri Lanka, documenting the systematic erosion of accountability mechanisms in Sri Lanka.

In recent months, Sri Lanka’s Government has stepped up its assaults on the independent functioning of the judiciary. In particular, the country’s Chief Justice was removed from office after she had challenged the legality of Government efforts to consolidate authority. The heavily politicized impeachment process was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka and was inconsistent with international human rights law and standards.

“In light of this resolution and the situation in Sri Lanka, the Commonwealth should change its plans to hold the 2013 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Colombo,” said Conte. “Sri Lanka has demonstrated its rejection of the Commonwealth Principles, notably democracy, the independence of the judiciary and human rights. This will no doubt be further confirmed when the High Commissioner for Human Rights presents her oral update to the Human Rights Council in September this year, just two months ahead of the scheduled Heads of Government Meeting.”

The ICJ has urged the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG), which meets next month, to address the human rights situation in Sri Lanka with the objective of removing its right to host the Heads of Government Meeting.

CONTACT:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director, (Bangkok); t:+66(0) 807819002; email: sam.zarifi(at)icj.org

Sheila Varadan, ICJ Legal Advisor, South Asia Programme (Bangkok); t: +66 857200723; email: sheila.varadan(at)icj.org

NOTES:

- The resolution of the Council was adopted by 25 votes in favor, 13 against and 8 abstentions (with Congo, Ecuador, Indonesia, Kuweit, Maldives, Mauritania, Pakistan, Philippines, Qatar, Thailand, Uganda, United Arab Emirates and Venezuela voting against; and Angola, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Malaysia abstaining)

- The resolution was led by the United States of America and co-sponsored by Austria, Canada, Estonia, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Spain, and Switzerland; as well as by the following non-member States of the Council: Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Monaco, Norway, Portugal, Saint Kitss and Nevis, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

- In January 2012, Chief Justice Dr Shirani Bandaranayake was removed in an impeachment process that violated international standards of due process and was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. The impeachment was widely condemned internationally. The ICJ issued a letter supported by fifty-six senior jurists from over thirty countries worldwide.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Open letter: Sri Lanka should not host the 2013 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting

ICJ calls for International Commission of Inquiry on accountability in Sri Lanka

The International Commission of Jurists welcomes key Human Rights Council resolution on Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka: judges around the world condemn impeachment of Chief Justice Dr Shirani Bandaranayake

Jan 22, 2013 | News

The ICJ today expressed its concern at further delays in the trial of President Desiré Delano Bouterse and 24 others, who are accused of the murder of thirteen civilians and two military personnel in 1982.

The ICJ today expressed its concern at further delays in the trial of President Desiré Delano Bouterse and 24 others, who are accused of the murder of thirteen civilians and two military personnel in 1982.

The ICJ further expressed its dissatisfaction with the continued uncertainty on the applicability of an Amnesty Law that could threaten the status of the trial.

No public statement has been made by the Suriname Military Court since the judges hearing the matter decided to suspend the trial of President Bouterse in May 2012 and leave it to the public prosecutor and an undesignated court to decide whether President Bouterse and the other accused should benefit from the country’s Amnesty Law.

“It is unacceptable that there have been no pronouncements in this case since the last hearing over eight months ago,” said ICJ Secretary-General Wilder Tayler. “Justice has been denied for more than three decades and it is in everyone’s interests, both the accused and the families of the victims, that this trial should proceed without further delay”.

President Bouterse had been accused of having been present on 8 December 1982 at the military barracks of Fort Zeelandia, where 15 political opponents were allegedly executed.

Reports published by various organizations at the time, including by an ICJ affiliate, indicated that several of the victims had also been subjected to torture. At the time, Bouterse was leading a military government in Suriname.

On 19 July 2010, Desiré Delano Bouterse was elected President of Suriname, taking up office on 12 August 2010. On 4 April 2012, despite some contestation, an amendment to the existing Amnesty Law of 1989 was adopted by the country’s Parliament, purportedly granting amnesty to President Bouterse and others for the murders that allegedly took place in 1982.

As the ICJ noted in its report of 29 May 2012, there are a number of unresolved questions regarding the legality of the Amnesty law.

Read also:

Suriname: independent observation mission to the trial of President Desiré Delano Bouterse

Jan 15, 2013 | News

The appointment of former Attorney General Mohan Peiris (photo) as Sri Lanka’s new Chief Justice raises serious concerns about the future of the Rule of Law and accountability in the country, the ICJ said today.

The appointment of former Attorney General Mohan Peiris (photo) as Sri Lanka’s new Chief Justice raises serious concerns about the future of the Rule of Law and accountability in the country, the ICJ said today.

Mohan Peiris has served in a variety of high-level legal posts in the past decade, always playing a key role in defending the conduct of the Sri Lankan government.

He served as Sri Lanka’s Attorney-General from 2009 to 2011. Since then he has served as the legal adviser to President Mahinda Rajapakse and the Cabinet.

“During his tenure as Attorney-General and the government’s top legal advisor Mohan Peiris consistently blocked efforts to hold the government responsible for serious human rights violations and disregarded international law and standards,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia director.

“Mohan Peiris’ appointment as the new Chief Justice, after a politically compromised and procedurally flawed impeachment, adds serious insult to the gross injury already inflicted on Sri Lanka’s long suffering judiciary.”

The International Commission of Jurists, in its recent report on impunity in Sri Lanka, highlighted Mohan Peiris’ lack independence as Attorney-General, noting the alarming number of cases involving prominent politicians that were withdrawn during his tenure.

In November 2011, as Attorney General, Peiris told the UN Committee Against Torture in Geneva that political cartoonist Prageeth Ekneligoda, believed to have been subjected to enforced disappearance in January 2010, had actually left Sri Lanka. In June 2012, Peiris admitted to a court in Colombo that this claim was groundless.

“ICJ condemns this appointment as a further assault on the independence of the judiciary and calls on the Sri Lankan government to reinstate Chief Justice Shirani Bandaranayake. If there are grounds for questioning the Chief Justice’s actions, they should be pursued following due process and a proper impeachment process.”

CONTACT:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director, Bangkok, t:+66 807819002; email: sam.zarifi(at)icj.org

Sheila Varadan, ICJ Legal Advisor, South Asia Programme, Bangkok, t: +66 857200723; email: sheila.varadan(at)icj.org

NOTE:

In a statement today (see below), Justice Bandarayanake strongly denied all the charges against her and asserted her status as the legal Chief Justice of Sri Lanka’s supreme court. She said: “The accusations leveled against me are blatant lies. I am totally innocent of all charges…Since it now appears that there might be violence if I remain in my official residence or my chambers I am compelled to move…”

Sri Lanka-CJ final speech-2012 (full statement, in pdf)

Read also:

ICJ condemns impeachment of Sri Lanka’s Chief Justice

Sri Lanka’s Parliament should reject motion to impeach Chief Justice

Impeachment of Sri Lankan Chief Justice: Government must adhere to international standards of due process

Jan 8, 2013 | News

The Nepali government should cooperate with any investigation into allegations of torture against Nepal Army Colonel Kumar Lama, recently arrested and charged in the United Kingdom, the ICJ said today.

The Nepali government should cooperate with any investigation into allegations of torture against Nepal Army Colonel Kumar Lama, recently arrested and charged in the United Kingdom, the ICJ said today.

“The ICJ welcomes the steps taken by the UK to criminally investigate and bring to justice an individual suspected of the serious crime of torture,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia Director. “If the government wants to prevent the future prosecution of conflict-era human rights violations in foreign countries, then it must cooperate with the UK proceedings, and take immediate steps to investigate and prosecute similar violations domestically, in line with Nepal’s own international obligations and the jurisprudence of Nepal’s Supreme Court.”

UK authorities arrested Colonel Lama on January 3rd for his alleged involvement in the torture of detainees while commander of the Gorusinge Battalion barracks in Kapilbastu in 2005.

Colonel Lama is currently serving as UN peacekeeper in the Sudan. At the time of the arrest, he was visiting family members who reside in the UK.

In response to the arrest, senior Nepali government leaders including the Deputy Prime Minister have called for his immediate release, and characterized the arrest as an “attack on national sovereignty.”

The ICJ pointed out that such statements seem to be predicated on a basic misunderstanding of both the UK and Nepal government’s international obligations to investigate and prosecute acts of torture, which are crimes under international law.

The Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment of Punishment, to which both the UK and Nepal are party, expressly provides under article 7 that a State must prosecute or extradite for prosecution a person found under its territorial jurisdiction.

This obligation is an expression of the legal principle of “universal jurisdiction,” under which all States have a duty, not only a right, to prosecute and punish crimes under international law, including torture, and to take effective measures including the adoption of national legislation to exercise jurisdiction over such crimes.

In many countries, including the UK, legislation grants the courts jurisdiction to prosecute certain international crimes, including torture, regardless of where the violations took place.

The UK legislation was passed as part of an effort to comply with international law, including the Geneva Conventions on the laws of war and the Convention Against Torture.

For the UK police to release Colonel Lama without conducting a full investigation, as called for by the government of Nepal, would constitute a violation of the UK’s own international obligations, the ICJ stresses.

“This arrest by the UK police is not a threat to the sovereignty of Nepal; on the contrary, the acceptance of international human rights legal obligations to combat torture constitutes a clear expression of sovereignty by both the UK and Nepal. The UK through its actions this week is rightfully discharging these obligations,” Zarifi said. “Nepali victims have been forced to seek redress outside their own country against perpetrators because of the government of Nepal’s track record of failing to prosecute conflict-era crimes.”

“Decades of experience from around the world demonstrates that the failure to provide truth and justice as a society transitions away from conflict hampers the development of a durable peaceful society. That’s why the Nepali government should do all it can to help thousands of Nepali victims receive truth and justice in Nepal, and wherever perpetrators may be hiding,” Zarifi added.

National courts are generally reluctant to invoke universal jurisdiction to prosecute foreign nationals, and usually only do so when it is clear that national authorities are unable or unwilling to investigate and prosecute the alleged violation.

In Nepal, successive governments have not only failed to show their commitment to prosecute these crimes, but have made systematic efforts to avoid accountability, and rewarded suspected violators with promotions, ministerial appointments and opportunities to participate in UN peacekeeping operations.

The ICJ advised the government of Nepal that the most effective way to prevent the future arrest and prosecution abroad of those alleged to have been responsible for torture and other gross human rights violations is to:

- Show its commitment to the international rule of law by cooperating with any investigation by the UK police into the culpability of Colonel Lama, including allowing police to visit Nepal if such a request is made as part of their investigation;

- Order the prosecution of serious crimes committed during the conflict to move forward, and end attempts to introduce an amnesty for such crimes;

- Introduce transitional justice legislation that is in line with Nepal’s obligations under international law, and precludes the granting of amnesty for serious crimes;

- End politically-motivated withdrawals of human rights cases now before Nepali courts; and

- Criminalize torture, enforced disappearance and other crimes under international law.

Contact:

In Kathmandu, for ICJ, Frederick Rawski: t +977-984-959-7681

In Bangkok, for ICJ Asia-Pacific, Sam Zarifi: t +66-807-819-002

FURTHER READING:

Nepal: ‘toothless’ commissions of inquiry do not address urgent need for accountability – ICJ report