Apr 9, 2021 | Advocacy, News

The ICJ, together with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan) in Indonesia, held a webinar on 6 April to consider ways to combat discrimination and violence faced by Indonesian women.

In particular, participants identified advocacy strategies towards strengthening Indonesia’s compliance with its international legal obligations under the UN Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

The webinar was broadcast live on Facebook and showcased the Bahasa Indonesia version of CEDAW video and attended by more than 50 women human rights defenders. The participants discussed the adequacy of measures taken by the Indonesian government to implement recommendations issued by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee) after it had reviewed Indonesia’s report in 2012. These recommendations included a call to repeal discriminatory by-laws adopted at the provincial level that restrict women’s rights in Aceh province and elsewhere; the adoption of measures taken to ensure that the draft or proposed amendments to the Criminal Code Bill and other bills do not contain provisions that discriminate against women; the need to address gender based violence and sexual violence against women including indigenous women; and the protection of women human rights defenders.

Devi Anggraini, Chairperson of Association of Indigenous Women of the Archipelago (Perempuan Aman) said although Indonesia had ratified CEDAW through Law No. 7 year 1984 to protect the individual rights of Indonesian women, policies had yet to effectively protect the collective rights of indigenous women. She shared her concerns regarding discrimination against Indigenous women in the context of large-scale development projects, exploitation of natural resources, deforestation, and expansion of agriculture, as well as their access to land and resources.

“The Indonesian government does not seek ‘free, prior, and informed consent’ by the affected indigenous people, especially indigenous women and this has caused 87.8% of indigenous women to lose control of their traditional lands,” said Devi.

Dian Novita, Coordinator of Policy Advocacy Division from Legal aid for Women and Children (LBH APIK Jakarta) raised concern about discriminatory draft laws and provincial laws.

“LBH APIK assists many cases of women who are victims of gender-based violence in which their videos containing private sexual conducts were distributed online. However, they were criminalized under the pornography law and Electronic Information’s and Transactions (EIT) Law. We are currently trying to pursue judicial review of the ETI Law from women’s perspective”, said Dian.

Andy Yentriyani, Head of Komnas Perempuan said that despite existing challenges and new obstacles, there had been some progress in responding to the Recommendations of the CEDAW Committee from the previous cycle, such as the enactment of Supreme Court Regulation no.3 year 2017 on guidance for judges in adjudicating cases involving women and similar gender sensitive regulation released by the Attorney General’s Office and the Police. “It is now our duty to monitor that these policies and training are effectively implemented. For example, we gained extraordinary support from the civil society during the campaign urging the Government to adopt the Sexual Violence Bill and this expanded participatory space for constructive dialogue for public to understand more about State responsibilities to protect and promote the fundamental rights of women.”

Watch

Contact

Ruth Panjaitan, Legal Adviser for Indonesia, e: ruthstephani.panjaitan(a)icj.org

Apr 2, 2021 | News

The Thai authorities’ adoption of a draft law to regulate non-profit groups would strike a severe blow to human rights in Thailand, several international organizations said today. The bill is the latest effort by the Thai government to pass repressive legislation to muzzle civil society groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

The “Draft Act on the Operations of Not-for-Profit Organizations” contains provisions that would have a deeply damaging impact on those joining together to advocate for human rights in the country, in violation of their right to freedom of association and other rights. The Thai government provided a perfunctory and inadequate consultation process for the bill. Because of fundamental problems in the draft law, the authorities should withdraw the draft entirely and ensure that any future law regulating NGOs strictly adheres to international human rights law and standards, the organizations said.

“This draft law poses an existential threat to both established human rights organizations and grassroots community groups alike. If enacted, this law would strike a severe blow to human rights by giving the government the arbitrary power to ban groups and criminalize individuals it doesn’t like,” said Maria Chin Abdullah, member of ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) and a Malaysian Member of Parliament (MP).

“This draft blatantly breaches Thailand’s own constitution and its human rights obligations. A thriving, independent and free civil society is an essential component of a rights-respecting, open society. The authorities should withdraw this deeply flawed draft and go back to the drawing board,” said Brad Adams, Director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia Division.

Arbitrary and vaguely-defined powers

According to the Draft Act (in Section 3), the government would have wide discretion as to which organizations will be exempted from the application of the law.

The Draft Act (in Section 4) also uses an overbroad definition of not-for-profit organizations (NPO), which has left it open to abusive and arbitrary application by the authorities.

The broad terms of the Draft Act would allow unequal treatment of certain disfavoured groups and carry dire consequences for associations critical of the government, with little scope to legally challenge government decisions. Groups as varied as academic institutions, community groups, sports associations, art galleries and ad hoc disaster relief collectives could be deemed to be NPOs and therefore be subject to the law’s mandatory registration requirement and potential criminal prosecution. The vague and overbroad definition of ‘not-for-profit organizations’ amounts to a violation of the “legality” principle, which requires any restriction to freedom of association and other fundamental freedoms be clearly “prescribed by law”.

Registered and unregistered groups alike must be allowed to function freely and be able to enjoy the right to freedom of association on equal terms. In order to enable individuals to exercise their right to freedom of association, States need to provide a simple, accessible, non-burdensome and non-discriminatory notification process for organizations to obtain their registration and must not require the authorities’ prior authorization.

“The draft law’s broad terms could be applied against virtually any group, no matter how small or informal,” said David Diaz-Jogeix, Senior Director of Programmes at ARTICLE 19. “If passed in its current form, the draft law will likely cause entire sectors of Thai civil society to collapse or take their activities underground.”

Excessive punishments

“Those found in breach of this law’s many faulty provisions risk lengthy prison sentences. Targetted NGOs could have their very existence extinguished at the whim of governmental authorities – enabling the silencing of critical and independent voices in Thailand,” said Ian Seiderman, Legal and Policy Director at the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ).

By making the registration of an NPO mandatory (in Section 5) and rendering any unregistered group illegal, the Draft Act would violate the right to freedom of association and severely impede the work of groups that defend and promote human rights.

Notably, under the proposed law (in Section 10), anyone found to belong to an unregistered association that operates within Thailand could be jailed for up to five years, fined up to 100,000 THB (approx. 3,200 USD), or both. This would effectively criminalize people solely for their peaceful exercise of the right to freedom of association.

“Paranoia” of foreign funding

“Around the world, bogus claims regarding foreign funding for NGOs are constantly used by repressive governments to distract from their own human rights record and to stigmatize and fuel paranoia regarding those who speak truth to power – often simply because they are critical of the government,” said Shamini Darshni Kaliemuthu, FORUM-ASIA’s Executive Director. “Now Thailand seems to want to follow suit, adding itself to an unwelcome list of rights-abusing governments trying to control or severely limit NGO funding.”

The Draft Act (in Section 6) places discriminatory restrictions on organizations that receive foreign funding. Authorities have the sole discretion to determine which activities may be carried out using funds from foreign or international sources, leaving ample room for abuse.

Moreover, the Draft Act states as a rationale for enacting the law: “several [NPOs] accepted money [from foreign sources], and used them to fund activities that may affect the relationship between the Kingdom of Thailand and its neighboring countries, or public order within the Kingdom.” This justification stigmatizes organizations that use foreign funding by equating their objectives to those of “foreign agents”. The government has failed to recognize the legitimate work carried out by organizations and their contribution to the rule of law and development of the country, merely because they are funded by foreign sources.

Privacy invaded and censorship on expression

“In addition to the ongoing criminalization of online expression in Thailand, the Draft Act gives sweeping, unchecked and discretionary administrative powers to the authorities to further obstruct the work of human rights organizations,” said Emerlynne Gil, Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for Research.

The Draft Act not only confers the power to the authorities to closely scrutinize organizations, it also contains provisions to subject NPOs’ offices and members to invasive surveillance and searches without judicial oversight. The Draft Act (in Section 6) allows the authorities to enter civil society organizations’ offices and make copies of their electronic communications traffic data without prior notice or a court warrant. This is a serious threat to the right to privacy and to freely express the ideas and opinions of its members.

Without prior notice or a valid warrant, this arbitrary power clearly violates domestic and international standards on due process of law.

“In going down this route, Thailand stands to poison the space for civil society. The passage of this law would severely undercut Thailand’s claims to be a rights-respecting country with a flourishing civil society,” said David Kode, Advocacy and Campaigns Lead at CIVICUS.

Contact

Ian Seiderman, ICJ Legal and Policy Director, ian.seiderman(a)icj.org, +41 229793800

Download

The statement with additional background information and list of organizations in English and Thai.

Submissions

Amnesty International

Article 19

Human Rights Watch

International Commission of Jurists – English and Thai

Apr 2, 2021 | News

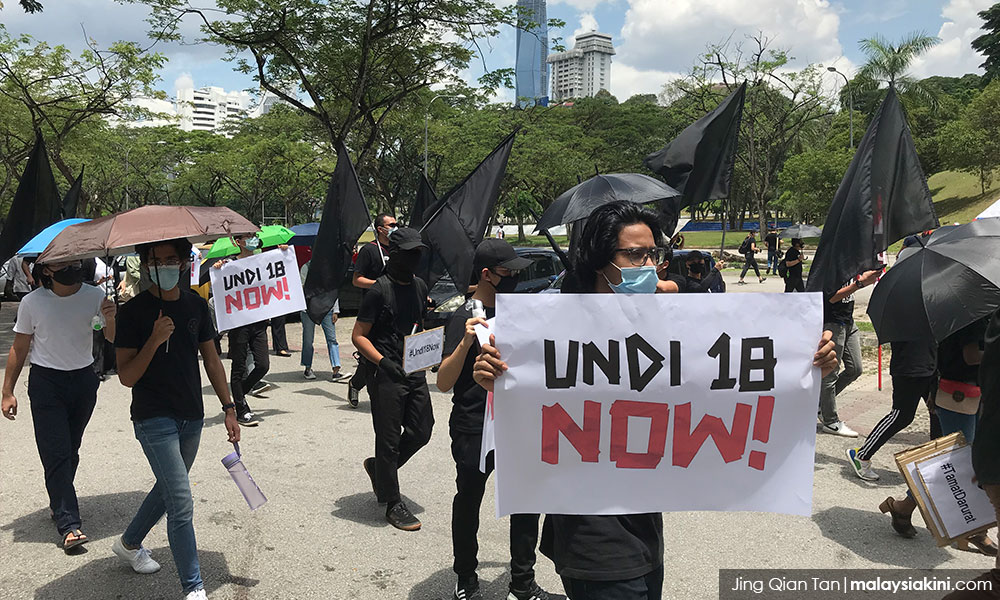

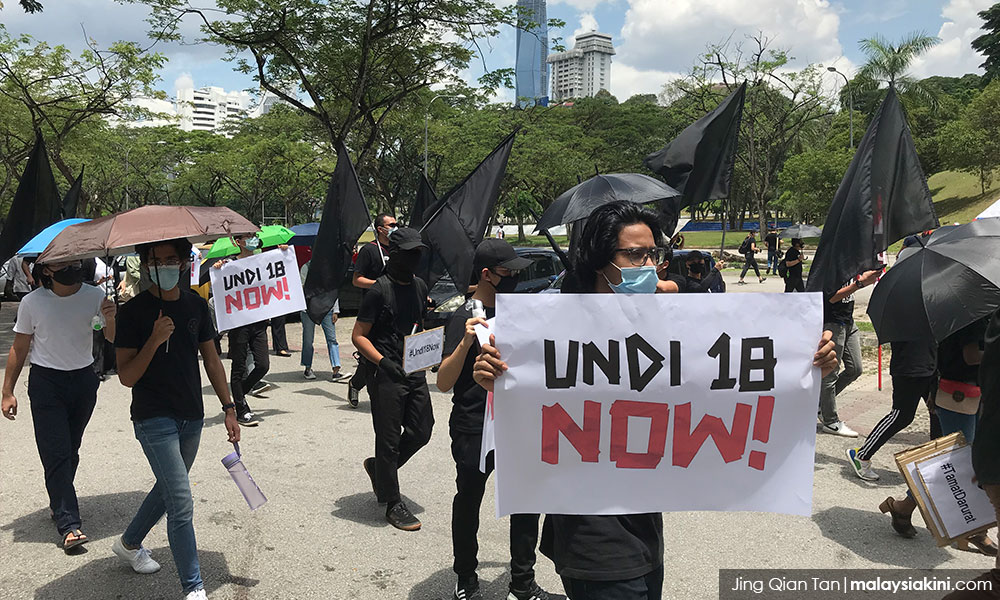

The ICJ today called on the Malaysian authorities to drop their criminal investigations of at least 11 participants in the peaceful Undi18 protests.

The Dang Wangi district police opened investigations against Dato’ Ambiga Sreenevasan, an ICJ Commissioner, and at least ten other individuals including Simpang Renggam MP Maszlee Malik, Petaling Jaya MP Maria Chin Abdullah, and Segambut MP Hannah Yeoh in relation to the wholly peaceful and socially distanced Undi18 protest rally held on 27 March 2021.

They are being investigated for alleged violations of section 9(5) of the Peaceful Assembly Act 2012 (‘PAA’) and Regulation 11 of the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases (Measures Within Infected Local Areas) (Conditional MCO) (No. 4) Regulations 2021 (‘MCO No. 4 Regulations’).

The ICJ said that the application of these laws against the protestors would not be consistent with international law and standards on freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.

The ICJ said that the investigations seem intended to harass and intimidate those who would exercise their rights to free expression and peaceful assembly.

If charged and convicted, violations of the PAA could result in a fine of up to RM$10,000 (approx. USD 2,410). Violations of the MCO No. 4 Regulations may result in a prison term of up to six months and/or a fine of RM$10,000 (approx. USD 2,410).

The ICJ reiterated its previous call for Malaysian legislators to reform the PAA, which imposes unjustifiably burdensome restrictions carrying excessive penalties on the exercise of freedom of expression and assembly.

Contact

Boram Jang, International Legal Adviser, Asia & the Pacific Programme, e: boram.jang(a)icj.org

Background

In July 2019, the Malaysian Parliament unanimously voted to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 years old.

On 25 March 2021, the Election Commission announced that it would postpone the implementation of this new rule from July 2021 to September 2022 at the latest. The Commission cited the COVID-19 lockdowns as a reason for the delay. This would affect the ability of 1.2 million people to vote, if elections are called later this year.

On 27 March 2021, hundreds of individuals gathered peacefully in front of Malaysia’ Parliament building to protest this delay. It was reported that the protestors were wearing face masks and trying to observe physical distancing, with some protestors donning full personal protective equipment.

On 29 March 2021, 11 individuals were summoned for questioning for alleged violations under section 9(5) of the PAA and Regulation 11 of the MCO No. 4 Regulations.

On 30 March 2021, eight of them gave their statements at the Dang Wangi police station in Kuala Lumpur. Four others, including Dato’ Ambiga Sreenevasan, will give their statements on 2 April 2021.

Section 9(5) of the PAA imposes a requirement for a five-day notice of an assembly to the Officer in Charge of the Police District. Failure to do so may result in a fine not exceeding RM$10,000 (approx. USD$2,410). Section 21A also allows the police to issue compounds of up to RM$5,000 instead of a charge being proffered subject to the written consent of the Public Prosecutor.

Regulation 11 of the MCO No. 4 permits the gathering or involvement in a gathering subject to any directions issued by the Director General. Regulation 17 states that failure to comply may result in a fine not exceeding RM$1,000 (approx. USD$241), imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months, or both. Additional emergency laws have raised the potential fine that may be imposed to up to RM$10,000 (approx. USD$2,410).

Mar 31, 2021 | News

Today, the ICJ submitted recommendations to Thailand’s Office of the Council of State concerning the Draft Act on the Operation of Not-for-Profit Organizations B.E. … (‘Draft Act’), which is scheduled for public consultation between 12 and 31 March 2021.

The ICJ urged that the Draft Act be repealed in its entirety or substantially revised in order to ensure compliance with Thailand’s international legal obligations.

The ICJ is concerned that the law, if adopted, would pose onerous and unwarranted obstacles to many civil society organizations in Thailand, including human rights NGOs, in carrying out their work. In its submission, the ICJ underscores the imprecise and overbroad language of the draft law, which would allow for abusive and arbitrary application by the Thai authorities on “Not-for-Profit Organizations” (NPOs). In particular, it provides for discriminatory restrictions on organizations that receive foreign funding.

“It is well-established in international law and standards that any registration of NPOs should be voluntary and that no law should outlaw or delegitimize activities in defence of human rights on account of the origin of funding,” said Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director.

Violators of the Draft Act would risk having their registration revoked. The Draft Act also imposes liability of criminal punishment on those who operate without registration with imprisonment not exceeding five years or fined not exceeding 100,000 THB (approx. 3,200 USD), or both.

“In cases of registration revocation, the legal recourse available for NPOs to challenge such decisions involves lengthy and burdensome administrative and judicial proceedings, which would normally take years to reach a conclusion. Proceedings of this kind will be untenable for some organizations and will deal a fatal blow to the essential work of many human rights defenders,” said Ian Seiderman.

The Draft Act also provides sweeping powers to government authorities to monitor activities, search and seize electronic data of NPOs without any court warrant, in violation of the rights to privacy.

Background

Thailand is a State party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which requires States to respect and protect, inter alia, the right to freedom of association, expression, peaceful assembly, the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs, the right to privacy and the right to an effective remedy. Thailand may impose limitations on NPOs only in narrow circumstances and subject to strict conditions as set out in the ICCPR.

On 23 February 2021, Thai Cabinet approved in principle the Office of the Council of State’s proposal to enact a law aims to provide oversight on NPOs’ operations.

The draft law is currently under consideration of the Council of State for legal review. Public consultation is currently carried out by the Office, only via their online platform. Members of the public were expected to have registered any concerns about the Draft Act through the website of the Office, by post or by email, between 12 to 31 March 2021 – a considerably tight period of time.

The draft law will then be resubmitted to the Cabinet, then presented to the Parliament.

Download

Recommendations in English and Thai (PDF)

Mar 30, 2021 | News

The ICJ today called for the reform of the country’s law on contempt of court to prevent their abuse and for the withdrawal of the contempt action filed against human rights lawyer Charles Hector.

Charles Hector faces potential contempt of court charges over a letter he sent to an officer of the Jerantut District Forest Office, as part of trial preparation. He is currently representing eight inhabitants of Kampung Baharu, a village in Jerantut, Pahang, in their civil lawsuit against two logging companies, Beijing Million Sdn Bhd and Rosah Timber & Trading Sdn Bhd.

The companies applied for leave to commence contempt of court proceedings against Charles Hector and the defendants. They claim that his letter violates an interlocutory injunction order prohibiting the villagers and their representatives from interfering with or causing nuisance to their work.

“Charles Hector is being harassed and intimidated through legal processes for carrying out his professional duties as a lawyer and gathering evidence in preparation for trial. The Malaysian authorities must act to protect human rights lawyers from sanctions and the threat of sanctions for the legitimate performance of their work,” said Ian Seiderman, the ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director.

The harassment of Charles Hector through legal processes violates international standards such as the UN Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers that make clear that lawyers must be able to perform their professional functions without intimidation, hindrance, harassment or improper interference.

Contempt of court, whether civil or criminal, may result in imprisonment and fines. Malaysia’s contempt of court offense is a common law doctrine and not codified statutorily.

“Fear of contempt charges stands to cast a chilling effect on the work of human rights lawyers and defenders. This further reinforces how Malaysia’s contempt of court doctrine needs to be urgently reformed as it is incompatible with international human rights law and standards,” said Seiderman.

The ICJ calls for the reform of Malaysia’s contempt of court doctrine to ensure clarity in definition, consistency in procedural rules and sentencing limits pertaining to criminal contempt cases. This reform should be in line with recommendations by the Malaysian Bar that the law of contempt be codified statutorily to provide clear and unequivocal parameters as to what really constitutes contempt.

Background

In September 2019, the two logging companies reportedly obtained approvals from the Jerantut District Forest Office to carry out logging in the Jerantut Tambahan Forest Reserve. The eight villagers are from a community many of whose residents have been protesting against the logging. The villagers depend on the forest reserve for clean water and their livelihoods.

On 14 July 2020, the companies filed a writ of summons against the eight villagers in the Kuantan High Court. The writ stated that the plaintiffs had applied for an injunction order to stop the defendants from preventing the companies’ workers from carrying out their works and spreading “false information” online.

On 5 November 2020, the companies successfully obtained an interlocutory injunction order. It was reported that the injunction order prohibits the defendants and their representatives from interfering with the approval given to the plaintiffs by the District Forest Office or causing nuisance to the work of the plaintiffs in any manner whatsoever, including physically, online or by communication with the authorities.

On 17 December 2020 Charles Hector sent a letter on behalf of his clients to Mohd Zarin Bin Ramlan, an officer of the Jerantut District Forestry Office, seeking clarifications on a letter sent by the office on 20 February 2020.

The logging firms contend that the letter violated the injunction order. In January 2021, the companies filed an ex parte application for leave to commence contempt of court proceedings against Charles Hector and the eight villagers.

The hearing was postponed until 25 March 2021 at the Kuantan High Court. On 25 March 2021, the plaintiff’s lawyer opposed the presence and participation of Charles Hector’s lawyer on the grounds that it was an ex parte application, which was contested by Charles Hector’s lawyer. The Court decided to adjourn the hearing to 6 April 2021.

Contact

Boram Jang, International Legal Adviser, e: boram.jang(a)icj.org

Mar 29, 2021 | Advocacy, News

On 25 March 2021, the ICJ filed two submissions to the UN Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) ahead of the review of Thailand’s human rights record in November 2021.

For this particular review cycle, the ICJ made two joint UPR submissions to the Human Rights Council.

In the joint submission by ICJ and Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR), the organizations provided information and analysis to assist the Working Group on the UPR to make recommendations addressing various human rights concerns that arise as a result of Thailand’s failure to guarantee, properly or at all, a number of civil and political rights, including with respect to:

- Constitution and Legal Framework: concerning the 2017 Constitution that continues to give effect to some repressive orders issued by the military junta after the 2014 coup d’état, the Emergency Decree, the Martial Law, and the Internal Security Act;

- Freedom of Expression and Assembly: concerning the use of laws that are not human rights compliant and, as such, arbitrarily restrict the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly, in the context of the Thai government’s response to the pro-democracy protests and, purportedly, to COVID-19; and

- Right to Life, Freedom from Torture and Enforced Disappearance: concerning the resumption of death penalty, the failure to undertake prompt, thorough and impartial investigations, and to ensure accountability of those responsible for the commission of torture, other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance, and the failure, to date, to enact domestic legislation criminalizing torture, other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance.

In the second, joint submission by ICJ, ENLAWTHAI Foundation and Land Watch Thai, the organizations provided information and analysis to assist the Working Group to make recommendations addressing various human rights concerns that arise as a result of Thailand’s failure to guarantee, properly or at all, a number of economic, social and cultural rights, including with respect to:

- Human Rights Defenders: concerning threats and other human rights violations against human rights defenders, and the restrictions on civil society space and on the ability to raise issues that the government deems as criticism of its conduct or that it otherwise disfavours;

- Constitution and Legal Framework: concerning the continuing detrimental impact of the legal framework imposed since the 2014 coup d’état on economic, social and cultural rights;

- Community Consultation: concerning the lack of participatory mechanisms and consultations, as well as limited access to information, for affected individuals and communities in the execution of economic activities that adversely impact local communities’ economic, social and cultural rights;

- Land and Housing: concerning issues relating to access to land and adequate housing, reports of large-scale evictions without appropriate procedural protections as required by international law, and the denial of the traditional rights of indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands and natural resources; and

- Environment: concerning the widespread and well-documented detrimental impacts of hazardous and industrial wastes on the environment, the lack of adequate legal protections for the right to health and the environment, and the effectiveness of the environmental impact assessment process set out under Thai laws.

The ICJ further called upon the Human Rights Council and the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review to recommend that Thailand should take various measures to immediately cease all aforementioned human rights violations; ensure adequate legal protection against such violations; ensure the rights to access to justice and effective remedies for victims of such violations; and ensure that steps be taken to prevent any future violations.

Download

UPR Submission 1 (PDF)

UPR Submission 2 (PDF)