Jul 13, 2017 | News

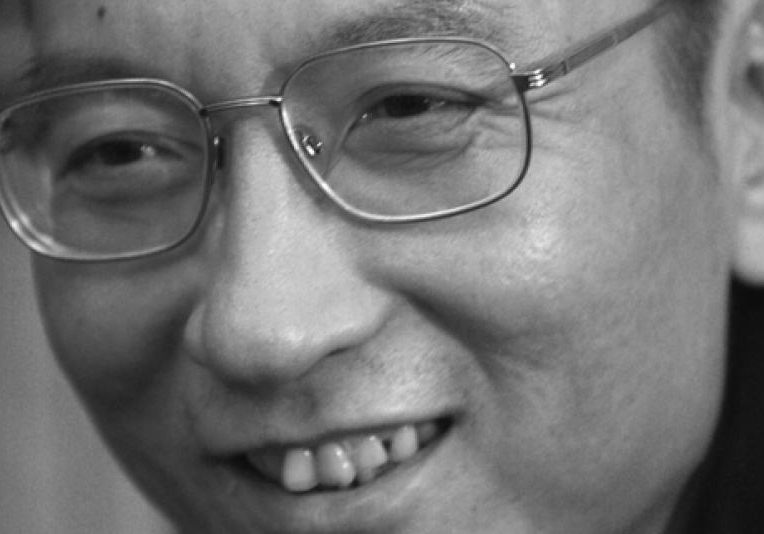

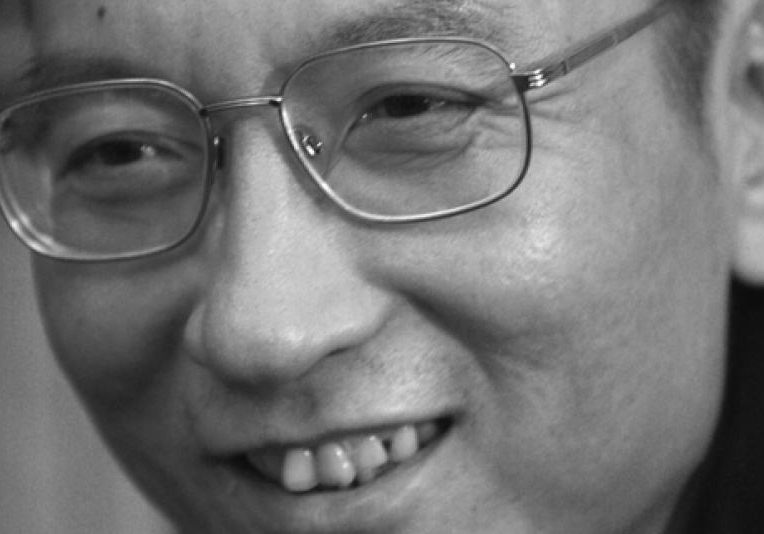

The ICJ today mourns the passing of Chinese human rights defender and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Liu Xiaobo. Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 and was described as the “foremost symbol of the struggle for human rights in China.”

He passed away today at the First Hospital of China Medical University, while still in the custody of Chinese authorities.

He has been imprisoned since 2009, after being found guilty for “subverting state power”, for calling for a new constitution in China. His wife, poet Liu Xia, remains under house arrest in Beijing.

In May 2017 authorities announced that he had been diagnosed with late-stage liver cancer.

Chinese authorities refused calls that he be allowed to travel to receive medical treatment abroad.

The ICJ honors Liu Xiaobo for his peaceful and unrelenting pursuit for human rights in China, and calls on the government to end the house arrest, and guarantee the freedom of movement, of Liu Xia.

Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Secretary General said: “Liu Xiaobo will continue to serve as an inspiration not only for those fighting for human rights in China, but also for all human rights defenders working to promote and protect human rights all over the world.”

The ICJ believes that the death of Liu Xiaobo should serve as a wake up call to the Government of China that they cannot simply and brutally silence dissenting voices.

Liu Xiaobo’s death only serves to amplify his call for human rights and upholding the rule of law in China.

The ICJ has consistently called upon the Chinese government to end the harrassment and unlawful detention of lawyers and human rights defenders.

Jun 30, 2017 | News

On 29 and 30 June, the ICJ co-organized a workshop for Cambodian civil society on the UPR.

The workshop was organized with the Cambodian Center for Human Rights, the Cambodia Country Office of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UPR Info, and the Cambodian Human Rights Committee on the mid-point review of the Human Rights Council’s (HRC) Universal Review (UPR) of Cambodia.

The Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) underwent its second UPR in January 2014.

The objectives of the workshop were to:

1. conduct a comprehensive mid-term assessment of the progress and challenges as of late June 2017 of the RGC’s implementation of those recommendations made during the second UPR cycle of Cambodia that the RGC had accepted with a view to informing advocacy around the September 2017 session of the HRC;

2. To take stock of the situation of UPR implementation to provide a basis for preparation of NGO shadow reports during the 3rd cycle of the UPR;

3. To discuss a specific set of UPR recommendations among relevant government bodies and civil society organizations in order to build relationships and raise awareness of the recommendations;

4. To advocate for the full implementation of the recommendations accepted during the second UPR cycle of Cambodia; and

5. To increase awareness of and demand among the Cambodian public for the implementation of the accepted UPR recommendations and to increase awareness of the HRC and UPR process.

Kingsley Abbott, Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia for the ICJ, moderated a panel discussion on “developing strategic advocacy plans for monitoring the implementation of UPR recommendations” and delivered a presentation on “strategies to effectively implement recommendations and lessons learned from other countries” focusing on past UPR cycles of Thailand Lao PDR.

After a comprehensive review of the recommendations accepted by the RGC during the last UPR cycle it was determined that many of the recommendations had not been implemented.

Civil society agreed that it was important to further strengthen coordinated efforts to monitor and conduct advocacy around the UPR process, engage constructively with the RGC, and begin preparation for the third UPR cycle focusing on lessons learned from the last cycle and regional experiences.

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, t: +66 94 470 1345 ; e: kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

Jun 29, 2017 | Advocacy, News, Non-legal submissions

The ICJ, together with other 60 national and international human rights organizations urged today the Myanmar authorities, and in particular the Ministry of Transport and Communication and the Parliament, to ensure the repeal of the offence of criminal defamation.

Myanmar-JointStatement-CriminalDefamation-2017-ENG (joint statement in English)

Myanmar-JointStatement-CriminalDefamation-2017-BUR (joint statement in Burmese)

Jun 26, 2017 | Advocacy

Amnesty International (AI) and the ICJ welcome the commitments made by the Royal Thai Government to prevent torture and other ill-treatment and urge authorities to ensure no further delay in implementing these undertakings.

The statement came on on the 30th anniversary of the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT) – marked on June 26 as the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture.

October 2017 will mark ten years since Thailand pledged to respect and protect the right of all persons to be free from torture and other ill-treatment by ratifying the Convention against Torture. AI and the ICJ however remain concerned that torture is still prevalent throughout the country.

Thailand has made significant and welcome commitments at the United Nations Committee against Torture, Universal Periodic Review of the Human Rights Council and UN Human Rights Committee to uphold its obligations under the Convention against Torture.

These include commitments to penalize torture, as defined in the Convention, under its criminal law and to create an independent body to visit all places of detention under the purview of the Ministry of Justice.

However, to date, these remain paper promises, which have not yet translated into action.

AI and the ICJ call on Thailand to move forward with these commitments, including by criminalizing torture and other acts of ill-treatment, establishing practical, legal and procedural safeguards against such practices, and ensuring that victims and others can report torture and other ill-treatment without fear.

The prohibition of torture and other ill-treatment in international law is absolute. Torture is impermissible in all circumstances, including during public emergencies or in the context of threats to public security.

AI and the ICJ regret repeated delays to the finalisation and passage of Thailand’s Draft Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Act.

If the remaining discrepancies with the Convention against Torture are addressed, the passage of this Act would criminalise torture and enforced disappearances and establish other safeguards against these acts.

Both organizations urge the Royal Thai Government to actualise its commitment to eradicating torture by addressing remaining shortcomings in the Act and prioritising its passage into law in a form that fully complies with Thailand’s obligations under the Convention against Torture and the Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

Additional consultations with the public and other parties should be carried out in a transparent and inclusive manner and without delay.

Similarly, AI and the ICJ urge Thailand to move ahead with its commitment to ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture, which obligates authorities to establish a National Preventive Mechanism – an independent expert body authorised to visit places of detention, including by carrying out unannounced visits – as well as to allow such visits by an international expert body.

Such independent scrutiny is critical to prevent torture and other ill-treatment, including through implementing their detailed recommendations based on visits.

Authorities should also act immediately on the commitment made at Thailand’s Universal Periodic Review before the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2016 to inspect places of detention in line with the revised UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, also known as the Nelson Mandela Rules.

Thailand-Torture satement AI-ICJ-Advocacy-ENG-2017 (full statement in English, PDF)

Thailand-Torture satement AI-ICJ-Advocacy-THA-2017 (full statement in Thai, PDF)

Jun 23, 2017 | News

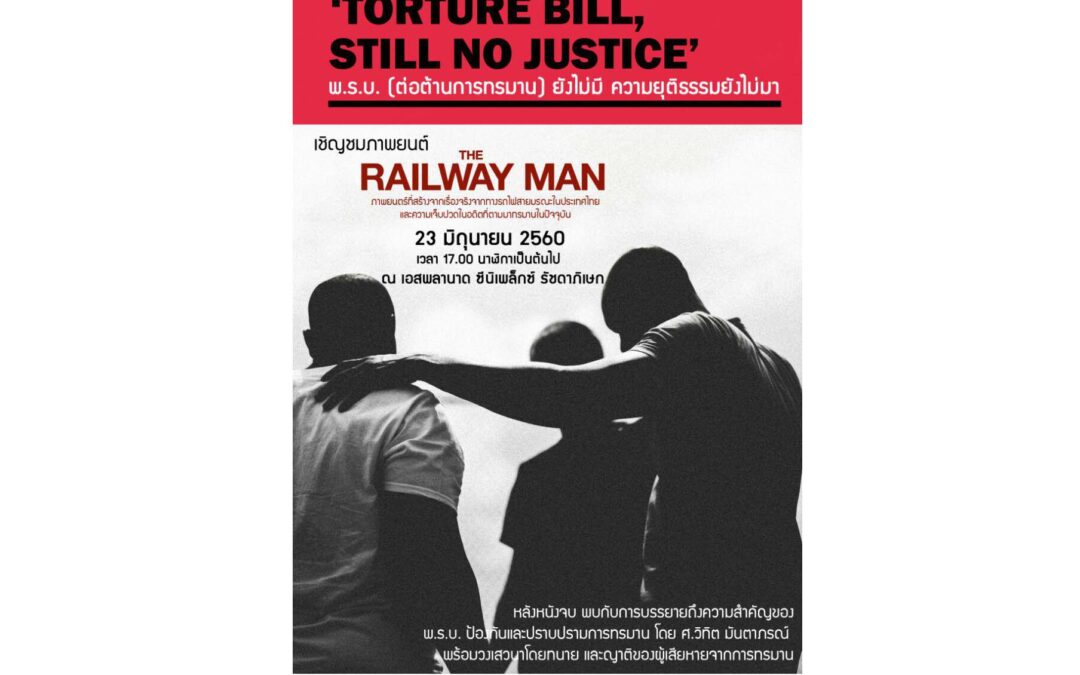

Today, the ICJ co-hosted an event in Bangkok, Thailand, named “Torture Bill, Still No Justice” to commemorate International Day in Support of Victims of Torture.

The event began with a keynote address by Professor Vitit Muntarbhorn, Special Rapporteur on violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity and former ICJ Commissioner.

Following a screening of the film “The Railway Man”, the ICJ moderated a panel discussion which included victims of torture.

The event focused on the decision in February this year of Thailand’s National Legislative Assembly (NLA) to further delay the passage of essential legislation criminalizing torture and enforced disappearance.

Thailand is a State party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), and has signed, but not yet ratified, the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED).

The other organizers of the event were the Southeast Asia Regional Office of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Amnesty International Thailand, the Cross-Cultural Foundation (CrCF), the Association for the Prevention of Torture (APT) and the Canadian Embassy in Bangkok.

A comic in English and Thai named “Torture is a Crime” was produced especially for the event by Shazeera Zawawi of APT.

Contact

Kingsley Abbott, ICJ Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, t: +66 94 470 1345 ; e: kingsley.abbott(a)icj.org

Thailand-Comic-Torture is A Crime-Advocacy-2017-ENG (English version of the comic, PDF)

Thai version here