Mar 24, 2021 | News

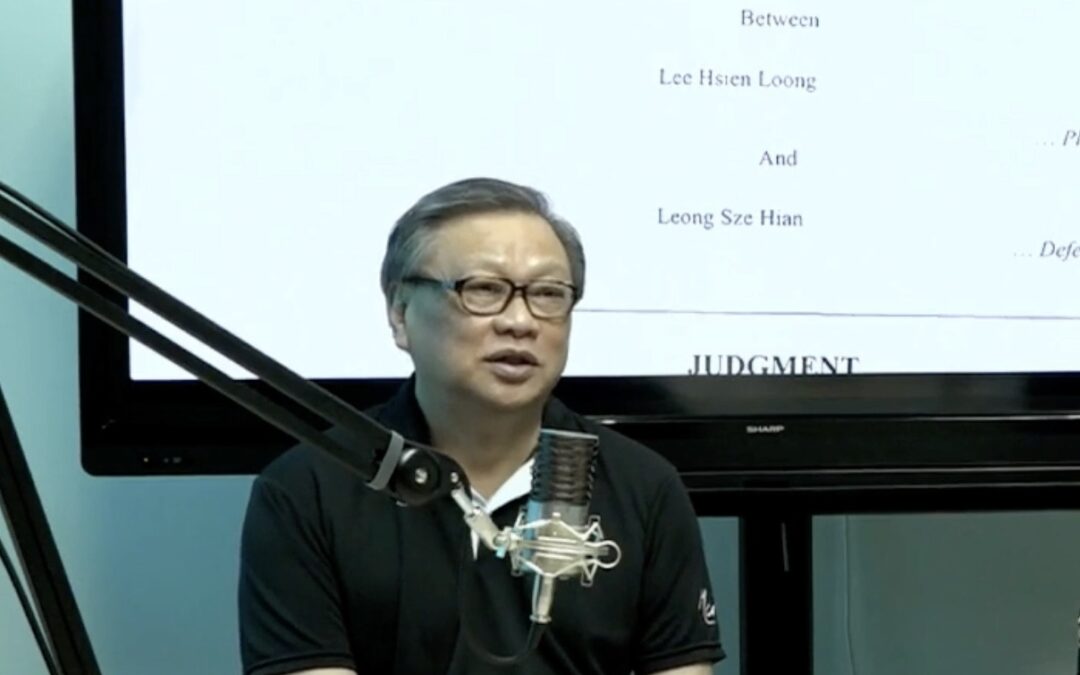

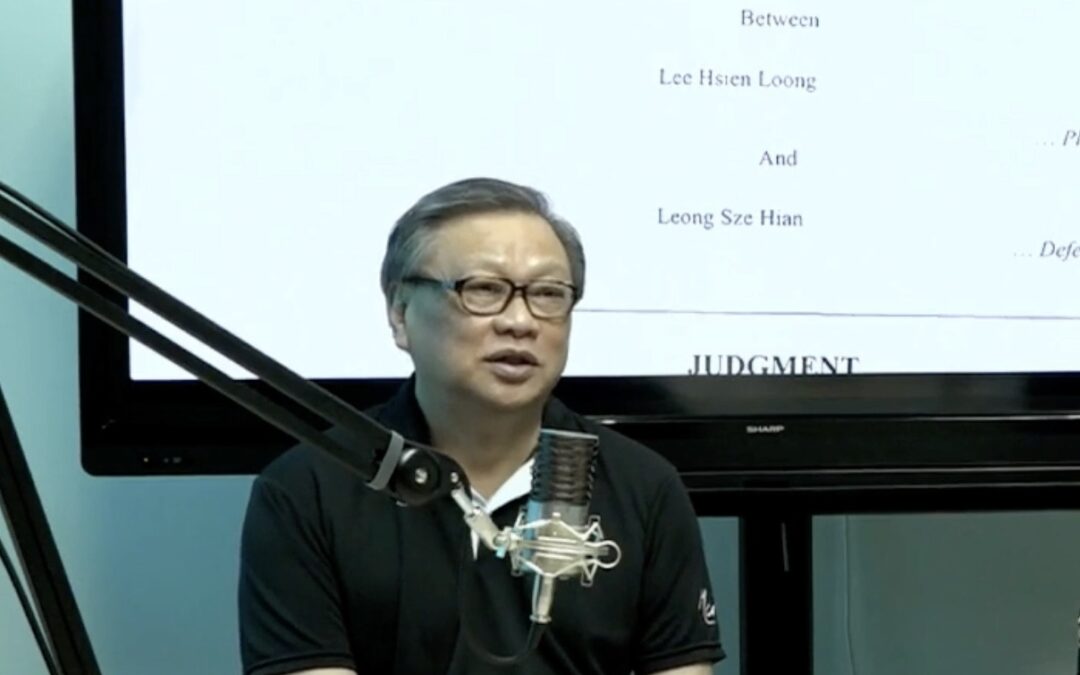

The High Court of Singapore decision ordering a blogger to pay the Prime Minister thousands of dollars in a defamation suit continues the country’s troubling trend of restricting online freedom of expression, the ICJ said today.

Mar 18, 2021 | News

The ICJ today condemned Sri Lanka’s new ‘de-radicalization’ regulations, which allow for the arbitrary administrative detention of people for up to two years without trial. The regulations could disproportionately target minority religious and ethnic communities.

Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa promulgated Prevention of Terrorism (De-radicalization from holding violent extremist religious ideology) Regulations No. 01 of 2021, which was publicized by way of gazette notification on 12 March, 2021. The “regulations”, which were dictated by the executive without the engagement of Parliament, would send individuals suspected of using words or signs to cause acts of “religious, racial or communal violence, disharmony or feelings of ill will” between communities to be “rehabilitated” at “reintegration centres” for up to two years without trial.

“These regulations, which have been dictated by executive fiat, allow for effective imprisonment of people without trial and so are in blatant violation of Sri Lanka’s international legal obligations and Sri Lanka’s own constitutional guarantees under Article 13 of the Sri Lankan Constitution.”

– Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director

Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Sri Lanka is a party, provides for a number of procedural guarantees for any person deprived of their liberty, many of which are absent in the Regulation. Administrative detention of the kind contemplated under the Regulations, is not permitted, as affirmed repeatedly by the UN Human Rights Committee.

Even prior to the promulgation of the new regulations under Sri Lanka’s Prevention of Terrorism Act No. 48 of 1979 (PTA), Sri Lankan authorities had already been invoking the PTA and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Act, No. 56 of 2007 (enacted to incorporate certain provisions of the ICCPR into domestic law) effectively to persecute people from minority communities. Yet little or no action has been taken by the authorities against those inciting hatred or violence against minorities.

“The new regulations are likely to be used as a bargaining tool where the option is given to a detainee to choose between a year or two spent in “rehabilitation” or detention and trial for an indeterminate period of time, instead of a fair trial on legitimate charges.”

– Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s Legal and Policy Director

Contact

Osama Motiwala, Communications Officer – osama.motiwala@icj.org

Background

Section 3(1) of the ICCPR Act which prohibits advocacy of hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, violence or hostility has hitherto been misused to target members of minority communities. In April 2020, Ramzy Razeek, a retired government employee, was arrested for a Facebook post calling for an ideological ‘jihad’ against the policy of mandatory cremation of people who had died as a result of Covid-19. He was detained under the ICCPR Act for more than five months and finally released on bail due to medical reasons in September 2020.

In May 2020, Ahnaf Jazeem, a young Muslim poet, was arrested under the PTA in connection with a collection of poems he had published in the Tamil language, which were apparently misinterpreted by Sinhalese authorities to be read as containing extreme messages. Just last week, a few days after the promulgation of the new regulations, Ahnaf’s lawyers expressed alarm that both Ahnaf and his father were being pressured to make admissions that he had engaged in teaching ‘extremism’. The ICJ had previously raised concerns about the arbitrary arrest and prolonged detention of Human Rights lawyer Hejaaz Hizbullah. After being detained under the PTA for 10 months without being given reason for his arrest, he is now being tried for speech-related offences under the PTA and ICCPR Act.

The ICJ has consistently called for the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act, which has been used to arbitrarily detain suspects for months and often years without charge or trial, facilitating torture and other abuse. The ICJ reiterates its call for the repeal and replacement of this vague and overbroad anti-terror law and regulations brought under it, in line with Sri Lanka’s international obligations.

The new PTA regulations require those who surrender or are arrested on suspicion of using words or signs to cause acts of violence, disharmony or ill will between communities to be handed over to the nearest Police Station within 24 hours after which a report is to be submitted by the Police to the Defence Minister (the position is currently held by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa) to consider whether the suspect should be detained further. The regulations would also apply to those who had surrendered or been taken into custody under the PTA, the Prevention of Terrorism (Proscription of Extremist Organizations) Regulations No. 1 of 2019 and the Emergency (Miscellaneous Provisions and Powers) Regulation, No. 1 of 2019.

The Attorney General is given the power to decide if a suspect should be tried for a specific offence or be send to a rehabilitation centre as an alternative. If the decision is to rehabilitate, the suspect would be produced before a Magistrate with the written consent of the Attorney General. The Magistrate may thereafter order that the suspect be referred to a rehabilitation centre for a period not exceeding one year. Such period can be extended by a period of six months at a time up to one more year by the Minister upon the recommendation of the Commissioner-General for Rehabilitation. The regulations further state that the Commissioner–General should provide the detainee with psycho-social assistance and vocational and other training during the rehabilitation period to ensure reintegration into society. The regulations also provide that such detainee may with the permission of the officer in charge of the Centre be entitled to meet their parents, relations or guardian once every two weeks.

Mar 17, 2021 | News

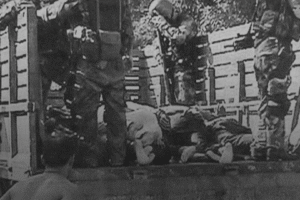

Imposition of Martial Law in several areas of Myanmar subjects civilians to trial by military tribunals, a dangerous escalation of the military’s repression of peaceful protests, said the ICJ today.

“Use of martial law marks the return to the dark days of completely arbitrary military rule in Myanmar. It effectively removes all protections for protestors, leaving them at the mercy of unfair military tribunals.”

– Ian Seiderman, ICJ’s director of law and policy

On 14 March, the Myanmar military issued Martial Law Order 3/2021, covering a number of townships of different provinces in Myanmar. According to this order, military officials assume full authority from civilian officials, and civilians may be subjected to military tribunals for charges of 23 violations of the criminal code and other laws. The 23 crimes include many of the charges used most against peaceful protesters in the past month, including charges of ‘disrupting or hindering government employees and services’ and ‘spreading false news’ about the government, and ‘exciting disaffection towards the government.’

The Martial Law Order also assigns disproportionately severe sentences, including the death penalty and prison sentences with hard labor. Judgments of military tribunals are not subject to appeal, even if the death penalty is imposed.

“Martial law has been imposed in precisely the areas where the military have used unlawful and lethal force against peaceful protesters, and removes even the pretense of access to courts for the people whose rights have been violated systematically by the military, ” said Seiderman.

The ICJ’s detailed review of military courts has documented that they lack competence, independence and impartiality to prosecute civilians. International law provides that the jurisdiction of military tribunals must generally be restricted solely to specifically military offenses committed by military personnel.

“The military courts lack transparency, due process and judicial oversights. It leaves no possibility to appeal the sentences, including the death sentences that have been handed down by military generals, ” said Seiderman.

Since the military coup d’etat of February 1 and the declaration of a state of emergency, the military has enacted and amended legislation enabling ongoing gross human rights violations, including possible crimes against humanity. More than 200 people have been unlawfully killed, with 2,000 more injured as security forces have used excessive force to suppress peaceful protests.

Background

On 14 March, the military-appointed State Administration Council, in accordance with Article 419 of the Constitution, enacted Martial Law Order 1/2021, imposing martial law in a number of areas in Yangon. The affected areas were further expanded through two other orders issued on 15 March, Martial Law Order 2/2021 and 3/2021. These orders transfer all power to the Military Commander in those areas. All local administration bodies have been placed under martial law, effectively giving military full control of all judicial and administrative processes.

The Order 3/2021 in particular is divided into six main sections with the most concerning provisions in relation to the list of crimes to be heard by military tribunals, and the proscribed punishments.

Contact

Osama Motiwala, ICJ Asia-Pacific Communications Officer, e: osama.motiwala(a)icj.org

Mandira Sharma: ICJ Senior Legal Adviser, e: mandira.sharma(a)icj.org

Mar 16, 2021 | Advocacy

This side event will take place on Tuesday 16 March 2021, from 14:00-15:00 (CET) at the 46th session of the UN Human Rights Council. For registration: https://bit.ly/3llCCMF

Minority Rights Group International and South Asia Collective, along with ICJ, OMCT, Article 19 and FORUM-ASIA, are hosting a side event at 46th session of the Human Rights Council, on hate speech and incitement in South Asia. The aim is to instigate discussion on the causes and consequences of hate speech in South Asia, in the hope of encouraging UN and its agencies to engage better on preventive and early warning actions in the region.

Speakers

- Fernand de Varennes – UN Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues

- Alice Wairimu Nderitu – UN Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide

- Haroon Baloch, Pakistan – Digital Rights Researcher, Bytes for All Pakistan

- Farah Mihlar, Srilanka – Lecturer, University of Exeter; Srilanka Minority Rights campaigner

- Shakuntala Banaji, India – Professor of Media, Culture and Social Change at London School of Economics

Moderator

- Joshua Castellino – Executive Director, Minority Rights Group International

Mar 15, 2021 | Advocacy, News

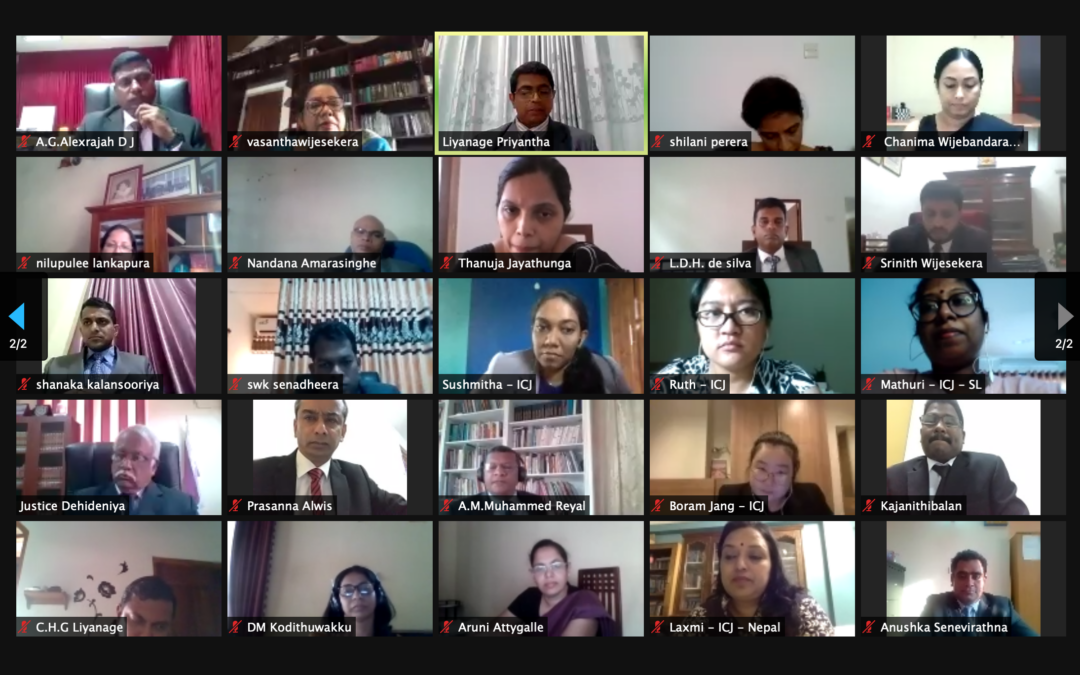

The ICJ and a group of Sri Lankan judges have agreed on the importance of taking effective measures to address discrimination and equal protection in accessing justice in the country.

On 6 and 13 March 2021, the ICJ, in collaboration with the Sri Lanka Judges’ Institute (SLJI), organized the National Judicial Dialogue on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and Enhancing Women’s Access to Justice. This event was organized under the ‘Enhancing Access to Justice for Women in Asia and the Pacific’ project funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA).

Twenty magistrates and District Court judges from around Sri Lanka, with judicial and legal experts from other countries, participated in this judicial dialogue which was conducted virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The dialogue highlighted how Sri Lankan women continue to face a myriad of challenges including legal, institutional and cultural barriers when accessing justice. Gender biases and discriminatory behaviour prevalent in every aspect of justice delivery needs to be dealt with in order to effectively enhance women’s access to justice.

Boram Jang, ICJ International Legal Advisor remarked that “judiciaries have an important role to play in eliminating gender discrimination in justice delivery as it is a critical component in promoting women’s access to justice. In order to do so, the judges should be equipped with a full understanding of Sri Lanka’s obligations under the CEDAW and other human rights instruments.”

Honorable L. T. B. Dehideniya, Justice of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka and Executive Director of the SLJI expressed hope that judicial dialogues such as this would “enhance the capacity of participant judges to use the international legal instruments, which Sri Lanka has ratified, in domestic judicial work especially with regard to the elimination of gender inequalities and biases.”

Ms. Bandana Rana, Vice Chair of the CEDAW Committee led a discussion with the judges on the application of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), pointing out that “judges play a pivotal role in identifying the incongruences between existing laws and international human rights standards and ensuring that the full gamut of women’s human rights is retained in line with the CEDAW framework.”

Justice Ayesha. M. Malik, High Court Judge, Lahore, Pakistan affirmed the importance applying the right to access to justice under international human rights law and suggested strategies for reflecting these international standards in judicial decisions.

Attorney Evalyn Ursua addressed on gender stereotypes and biases in justice delivery and engaged the participants on how these could be effectively eliminated. She stated that “the judiciary as a part of the State has the obligation to eliminate gender discrimination.” She encouraged the judges to use the cultural power of law to change language and attitudes surrounding gender discriminatory behaviour and stigma.

The second day featured a discussion on the specific barriers that women in Sri Lanka face when they access justice. Hon. Shiranee Tilakawardane, former Justice of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka led a discussion on the role and measures available to the judiciary as an institution to enhance access to justice for Sri Lankan women.

Justice Tilakawardane stated that “While theoretically, the Sri Lankan constitution enshrines equality before the law, in reality women continue to feel disadvantaged when they try to access justice” and added “the Sri Lankan judiciary can empower its women only when it understands, acknowledges and addresses the disadvantages they face owing to their gender.” She impressed upon the participant-judges that “ensuring equality is no longer a choice, nor is it merely aspirational, but a pivotal part of judicial ethics.”

The panelists on the second day surveyed the legal, institutional and cultural challenges faced by women at every step of the judicial process. The panel comprised of Prof. Savitri Goonesekere, Emeritus Professor of Law and Former member of the CEDAW Committee, Mrs. Farzana Jameel, P.C, Additional Solicitor General of the Attorney General’s Department and Mrs. Savithri Wijesekara, Executive Director of Women in Need.

Contact

Osama Motiwala, Communications Officer – osama.motiwala@icj.org