Apr 24, 2020 | News

On 24 April 2020, the ICJ, Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) and the Cross Cultural Foundation (CrCF) made a joint supplementary submission to the UN Human Rights Committee on Thailand’s implementation of its human rights obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

In their submission, the ICJ, TLHR and CrCF detailed their concerns in relation to Thailand’s failure to implement the Committee’s recommendations, including the ongoing human rights shortcomings of the country’s Constitutional and legal framework; the continued lack of domestic legislation criminalizing torture, other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance; and reports of torture and other ill-treatment. In addition, the three human rights organizations expressed concern over the use of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situation to combat the COVID-19 outbreak, and measures imposed under the Decree that may constitute a blanket restriction on fundamental freedoms, including the rights to free expression, opinion, information, privacy and freedom of assembly and association, with no opportunity for the courts to review these extraordinary measures.

The organizations’ submission also describes human rights concerns with respect to the following:

Constitution and legal framework

- Head of the NCPO Order No. 22/2561; and

- Head of the NCPO Order No. 9/2562

Extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances and torture

- continued lack of domestic legislation criminalizing torture, other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance;

- reports of extrajudicial killings, torture, other ill-treatment, enforced disappearances, and the progress and results of investigations;

- the application of security-related laws; and

- threats and reprisals against persons working to bring to light cases of alleged torture, ill–treatment and enforced disappearance.

Download

Thailand-UN-Human-Rights-Committee-Supplementary Submission-2020-ENG (English, PDF)

Thailand-UN-Human-Rights-Committee-Supplementary Submission-2020-THA (Thai, PDF)

Background

On 23 March 2017, during its 119th Session, the Human Rights Committee adopted its Concluding Observations on the second periodic report of Thailand under article 40 of the ICCPR.

Pursuant to its rules of procedure, the Committee requested Thailand to provide a follow up report on its implementation of the Committee’s prioritized recommendations made in paragraphs 8 (constitution and legal framework) 22 (extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances and torture) and 34 (conditions of detention), within one year of the adoption of its Concluding Observations – i.e., by 23 March 2018.

On 18 July 2018, Thailand submitted its follow-up report to the Committee. The report was published on 9 August 2018.

On 27 March 2018, the ICJ, TLHR and CrCF made a joint follow-up submission to the UN Human Rights Committee. However, since then, there have been several developments that the three organizations wish to bring to the attention of the Committee through this supplementary submission.

The UN Human Rights Committee will review Thailand’s implementation of the prioritized recommendations during its 129th Session, in June/July 2020.

Further reading

ICJ and TLHR, Joint submission to the UN Human Rights Committee, 13 February 2017

ICJ, TLHR and CrCF, Joint follow-up submission to the UN Human Rights Committee, 27 March 2018

Apr 22, 2020 | Advocacy, News

The ICJ based on the consultations with the participants of the Regional Forum of Lawyers held in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, published recommendations on the Independence of Legal Profession and Role of Lawyers in Justice Systems of the Central Asian States.

The recommendations draw attention of State and non-State actors in the Central Asian countries to the urgency in ensuring in law and practice the independence of the lawyers’ professional associations and individual lawyers.

“Lawyers play a critical role in strengthening the rule of law and protection of human rights in the justice systems of all countries of the world, including in Central Asia,” Temur Shakirov, ICJ Senior Legal Adviser said.

“We hope that these recommendations, which are based on consultations and international law and standards on the role of lawyers, will contribute to strengthening the independence lawyers and Bar Associations in Central Asia”.

The recommendations, apart from the lawyers’ communities themselves, are addressed to national professional associations of lawyers, Parliaments, and Governments, and specifically Ministries of Justice that continue in some countries of Central Asia to exercise formal and informal influence over the national Bar Association, including by imposing control in regard to access to the profession and disciplinary proceedings.

“The ICJ calls on these institutions to adopting urgent and effective measures legal and policy measures to safeguarding lawyers’ ability to carry out their professional duties in an atmosphere free from any other improper interference, institutional or personal, in each of the countries of the Central Asian region,” Shakirov added.

Background:

On 9 November 2018, the ICJ facilitated the Regional Forum on the Independence in Justice Systems of the Central Asian States in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. This was the first regional event hosted by the Union of Lawyers of Tajikistan, a professional association of lawyers that was established in 2014. The Forum brought representatives of the National Bar Associations of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, the Republic of Tajikistan and the Republic of Uzbekistan. The event was also supported by Legal Policy Research Centre (LPRC), a think tank from Almaty, Kazakhstan, that works on the reform of legal profession in the region.

The participants of the Forum highlighted the continuing and renewed attempts to undermine the independence of the professional associations of lawyers in countries of Central Asia, including targeted disbarment and harassment of individual lawyers for fulfilment of professional duties towards their clients. The participants also discussed the emerging practice of the establishment of specialized bodies for the protection of the rights of lawyers within the professional associations of lawyers to counter negative trends in Central Asian countries, affecting the legal profession.

Recommendations, in PDF: Central Asia-Recommendations-Advocacy-2020-ENG

Apr 21, 2020 | News

The ICJ called upon the Sri Lankan authorities to respect human rights in the conduct of their investigation of the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings, including ensuring that investigations into the alleged involvement of Sri Lankan lawyer, Hejaaz Hizbullah, are conducted in accordance with due process and fair trial guarantees under international law.

Specifically, the authorities must specify the charges against him, grant him full and immediate access to a lawyer, and investigate the circumstances of his arrest for potential rights violations.

Sri Lankan Lawyer Hejaaz Hizbullah was arrested by the Criminal Investigation Department of the Police (CID) on April 14, 2020 pursuant to the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and has since been kept in detention. No reasons were provided at the time of the arrest. During a media briefing, a police spokesperson stated that he was arrested as a result of the evidence found against him during investigations into the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings. The ICJ understands that no remand or detention orders authorising his continued detention have been served even after the lapse of 72 hours as required by Sections 7 and 9 of the PTA. Moreover, Hizbullah was only granted limited access to legal counsel on April 15 and 16, under the supervision of a CID official, who had insisted that the conversation be in Sinhala, in breach of attorney-client privilege. Legal access has been denied at least since April 16, 2020.

“No one questions the government’s need and obligation to investigate the horrendous Easter Sunday attacks, but these investigations must be conducted in a way that is consistent with international law and the Sri Lankan Constitution,” said Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia-Pacific Director. “Not serving Hizbullah a remand order as required by law, and denying him full and confidential access to legal counsel is unacceptable and in violation of international standards on the right to liberty.”

A Habeas Corpus petition was filed by Hizbullah’s father on April 17 seeking his release from detention, and demanding that he be given access to his attorneys. According to the application, five persons posing as officials of the Ministry of Health entered his home and interrogated him, after placing him in handcuffs. They demanded access to two of his case files, recorded a statement from him and subsequently took him into custody at the Criminal Investigation Department.

“By allowing warrantless entry, search of premises and the arrest of persons, the Prevention of Terrorism Act violates basic due process guarantees under international law,” added Rawski. “This legal provision is one of many problematic provisions of the PTA. The ICJ reiterates it calls for the PTA to be repealed, and replaced with an a law that conforms with Sri Lanka’s international human rights obligations.”

According to Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, “anyone who is arrested shall be informed, at the time of arrest, of the reasons for his arrest and shall be promptly informed of any charges against him.” Article 14 entitles anyone charged of a criminal offence “to have adequate time and facilities for the preparation of his defence and to communicate with counsel of his own choosing”. Similar guarantees are enshrined under Article 13 of the Sri Lankan Constitution.

The UN Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers provide that, “Governments shall further ensure that all persons arrested or detained, with or without criminal charge, shall have prompt access to a lawyer, and in any case not later than forty-eight hours from the time of arrest or detention.”

The ICJ has consistently called for the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act, which has been used to arbitrarily detain suspects for months and often years without charge or trial, facilitating torture and other abuse. The ICJ reiterated its call for the repeal and replacement of this vague and overbroad anti-terror law in line with international human rights standards and Sri Lanka’s international obligations.

Contact

Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia-Pacific Director, t: +66 64 478 1121; e: frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

Apr 18, 2020 | News

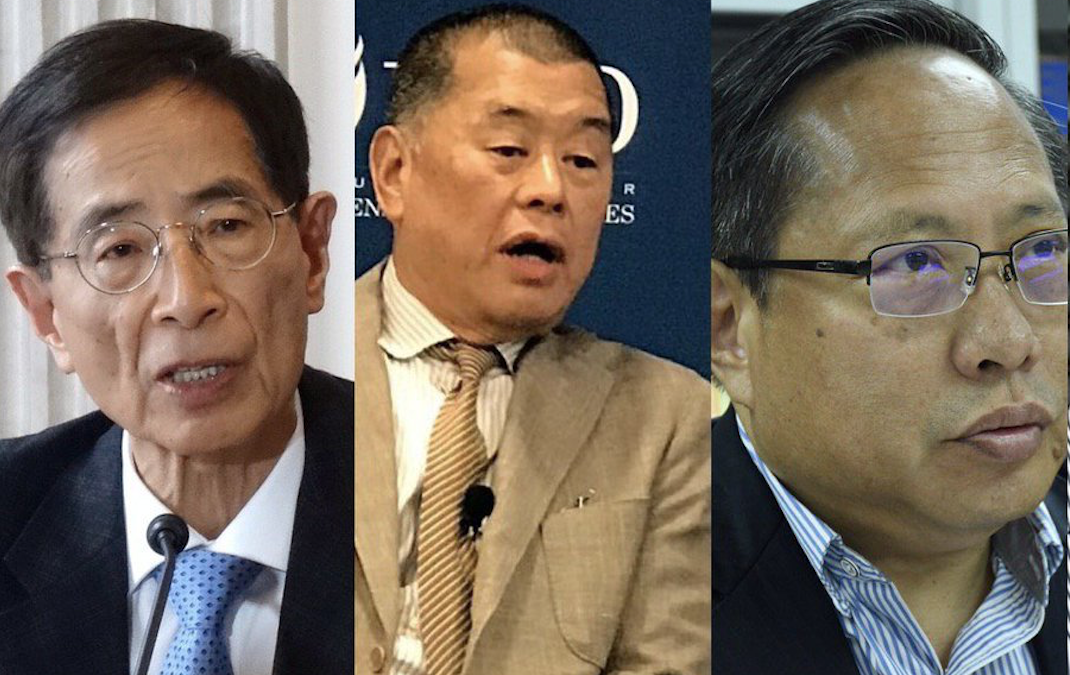

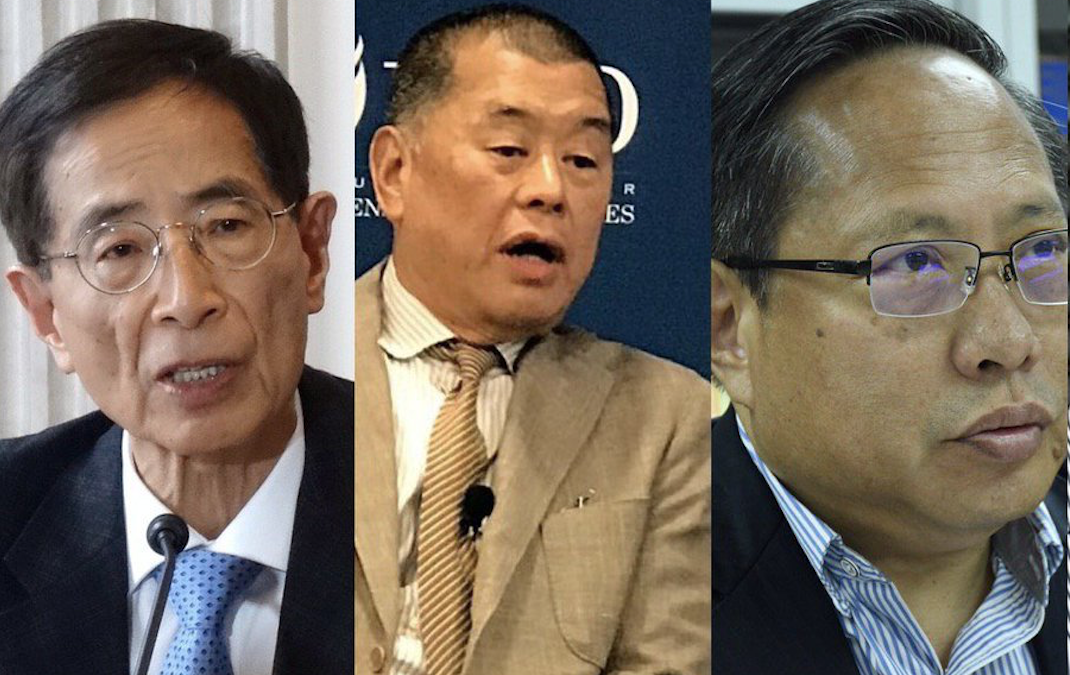

Today the ICJ joined other legal organizations in condemning the arrest of 15 pro-democracy figures in Hong Kong for organizing and taking part in ‘unauthorized assemblies’ in 2019. The arrests demonstrate the continued assault on the freedom of expression and the right to assembly in Hong Kong.

The joint statement reads:

The international legal community is seriously concerned by the arrest of 15 veteran pro-democracy figures in Hong Kong on Saturday 18 April 2020. In what appears to be a further clampdown on civil liberties and democracy following the 2019 protests, which began over the introduction of a controversial extradition bill, those arrested today include senior figures in the pro-democracy movement. These include lawmakers, party leaders and lawyers such as the democratic politician and legislator, Martin Lee QC who was also involved in the drafting of the Basic Law, the media owner, Jimmy Lai, and the barrister, Dr Margaret Ng. In October of last year, Margaret Ng and Martin Lee were jointly awarded the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Award for their lifelong defence of freedom, democracy and the rule of law.

The arrests are purported to be based on suspicion of organising and taking part in ‘unauthorised assemblies’ on 18 August, 1 October and 20 October 2019, pursuant to the Hong Kong SAR Public Order Ordinance. No explanation has been reported for the apparent delay between those protests and the timing of today’s arrests. The leaders of the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement have long argued for their rights to peaceful assembly and protest to be exercised without the need for consent from the authorities.

The right to peaceful protest is protected under the Joint Declaration and the Basic Law. As part of the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ policy, the Hong Kong Basic Law guarantees freedoms that are not available to those in mainland China until 2047. Hong Kong residents are guaranteed the rights to ‘freedom of speech, of the press and of publication; freedom of association, of assembly, of procession and of demonstration’. Article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) provides that “[t]he right of peaceful assembly shall be recognised.” The Basic Law expressly preserves the ICCPR as applicable to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The State has a duty to protect and facilitate such protest, and the Public Order Ordinance must be implemented in conformity with Hong Kong’s obligations under the ICCPR.

Following growing concerns of eroding civil liberties and the rule of law in Hong Kong, the 2019 protests have been unprecedented in their scale and reach and have led to physical violence by authorities, as well as a regrettable violent response by a minority of demonstrators. Excessive crowd dispersal techniques have been used by the authorities, including the dangerous use of tear gas, water cannons, firing of rubber pellets, pepper spray and baton charges by the police to disperse pro-democracy demonstrations, and there is reliable evidence of violence upon arrest. No proper investigation into excessive force has taken place and indeed calls from the international community, including the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights, have been rejected.

Today’s arrests demonstrate the continued assault on the freedom of expression and right to assembly in Hong Kong. Indeed, we are gravely concerned that the arrests of senior lawyers and legislators who set out to protect human rights in a non-violent and proportionate manner, and pursuant to both rights granted in both domestic and international legal frameworks, represent an assault on the rule of law itself. The United Nations Human Rights Committee has repeatedly expressed concern that charges of ‘unlawful assembly’ against peaceful protesters in Hong Kong risks violating human rights. The arrest of a prominent media owner also sends a chilling message to those whose journalism is vital to a free society.

It is critical that authorities do not use their powers to encroach on fundamental human rights, and it is vital that legal systems continue to protect citizens from any abuse of power which may otherwise be unseen during the COVID-9 crisis in which the international community is submerged..

We strongly urge the Hong Kong authorities to immediately release the 15 individuals arrested and drop all charges against them. Moreover, we call on the authorities to discontinue such politicised and targeted prosecutions immediately and urge the Hong Kong government instead to engage in constructive dialogue with the leaders of the pro-democracy movement to foster a climate in which their legitimate concerns over democracy and human rights can be met.

To download the statement with more information and list of organizations, click here.

Apr 17, 2020 | News

On the sixth anniversary of the apparent enforced disappearance of Karen activist, Pholachi “Billy” Rakchongcharoen, the ICJ repeated its calls for Thailand to bring those responsible to justice and apply appropriate penalties that take into account the extreme seriousness of the crime.

On 23 December 2019, after the Thai Ministry of Justice’s Department of Special Investigation (DSI) in September had located bone fragments which they identified as likely belonging to Billy, eight charges, including premeditated murder and concealing the body, were brought against four officials of Kaeng Krachan National Park, with whom Billy was last seen. However, in January 2020, public prosecutors suddenly dropped seven murder-related charges against the four accused on the basis that there was insufficient evidence to take the cases to trial.

“It is disturbing that after six years the prosecutors could not move forward with the prosecution because the authorities failed to gather evidence to identify the perpetrator for Billy’s murder despite the discovery of bone fragments,” said Frederick Rawski, Asia Regional Director of the ICJ. “Thai authorities should, pursuant to its international legal obligations, continue to gather other direct and circumstantial evidence to prosecute and punish perpetrator with appropriate penalties.”

The four suspects are now facing only a minor charge for failing to exercise their official functions because they released Billy instead of handing him over to the police after they took him into custody in April 2014 for collecting wild honey in the park.

“Thailand needs to implement legislation criminalizing enforced disappearance without delay so that prosecutors have the appropriate tools to prosecute those responsible, and are not forced to bring charges for crimes of lesser gravity,” he added.

Download the statement with detailed background information in English and Thai.

Contact

Frederick Rawski, ICJ Asia-Pacific Director, t: +66 64 478 1121; e: frederick.rawski(a)icj.org

Further reading

Thailand: discovery of “Billy’s” remains should reinvigorate efforts to identify perpetrator(s)

Thailand: continuing delay in the enactment of the draft law on torture and enforced disappearance undermines access to justice and accountability