Jun 8, 2015 | News

While the constitution of Pakistan’s first National Commission for Human Rights is welcome, the Commission risks being toothless unless its powers are extended to investigate human rights violations allegedly committed by the security agencies, the ICJ warned today.

The ICJ was informed that members of the National Commission for Human Rights were notified on 20 May 2015, three years after the National Commission for Human Rights Act was passed in June 2012.

“The establishment of a national human rights commission is a much-needed step for the promotion and protection of human rights in Pakistan,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia Director. “But for the new Commission to be able to assist the people of Pakistan, who face tremendous violations of their rights in terms of civil, political, social, economic, and cultural rights, it must be able to address the conduct of the country’s powerful military and security agencies.”

Under the National Commission for Human Rights Act, the Commission’s powers include investigating human rights violations, suo motu or on petition; visiting detention centers to ascertain the legality of the detention of detainees and ensure detainees are treated according to law; reviewing and suggesting amendments to Pakistan’s constitutional and legal framework on human rights; making recommendations for the effective implementation of international human rights treaties; and developing a national plan of action for the promotion and protection of human rights.

The law provides that while inquiring into complaints under the Act, the Commission shall have all powers of a civil court, including summoning and ensuring attendance of witnesses, receiving evidence on affidavits; and discovery and production of documents.

However, the Commission’s mandate is very limited where the armed forces or security agencies are accused of committing human rights violations, the ICJ says.

The law specifically states that “the functions of the Commission do not include inquiring into the act or practice of the intelligence agencies”.

Where the armed forces are accused of human rights violations, the Commission is only authorized to seek a report from the Government and make recommendations.

“The Commission’s restricted mandate over the armed forces, and especially the intelligence agencies, is of grave concern given that Pakistan’s military and intelligence services are accused of perpetrating gross human rights violations, including enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and torture and ill-treatment,” Zarifi said. “A human rights commission that does not have jurisdiction over abuses by these actors risks being toothless and ineffective – and worst, a cover for continuing government inaction in response to these violations.”

“With these exceptions in place, it seems questionable that the Commission will get accreditation by the International Coordinating Committee of NHRIs, which is a requirement for a National Human Rights Institution to be recognized internationally,” he added. “The Pakistani government should ensure that the Commission complies with international standards so it can help protect and promote the rights of all people in Pakistan.”

Additional Information:

Justice (r) Ali Nawaz Chohan was appointed as the Chairperson of the Commission. Other members include one representative from each province; one representative each from the Islamabad Capital Territory and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas; the Chairperson of the National Commission on the Status of Women; and a member belonging from a religious minority community.

The UN Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions (Paris Principles) provide the minimum standards required by national human rights institutions to be considered credible and effective, and get accreditation by the International Coordinating Committee of NHRIs. Section 3 (a) (ii) of the Paris Principles states that a NHRI should have the power to hear a matter without higher referral over “any situation of violation of human rights which it decides to take up”.

Section 4 of the National Commission on Human Rights Act, 2012, provides the following procedure for appointment of members of the Commission: the Federal Government invites nominations for commissioners through public notice; the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition scrutinize the nominations; and the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition forward three names for each member of the commission to a parliamentary committee for confirmation. The law provides that the parliamentary committee would comprise of two members of the National Assembly (lower house) and two members of the Senate (upper house) –with two members each from the government and two from the opposition.

Contact:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia Pacific Regional Director (Bangkok), t: +66 807819002; e: sam.zarifi(a)icj.org

Reema Omer, ICJ International Legal Adviser for South Asia (London), t: +44 7889565691; e: reema.omer(a)icj.org

May 27, 2015 | News

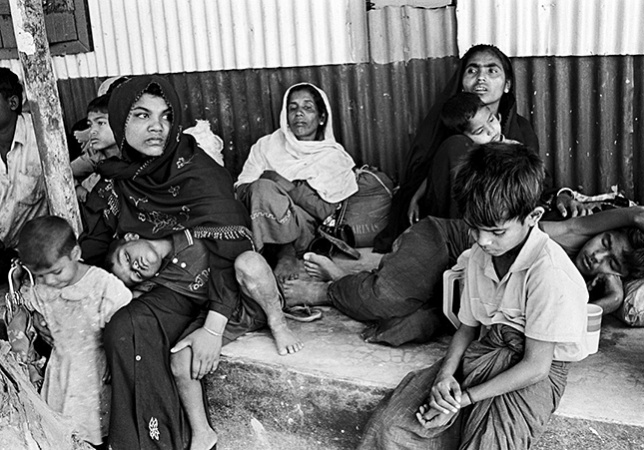

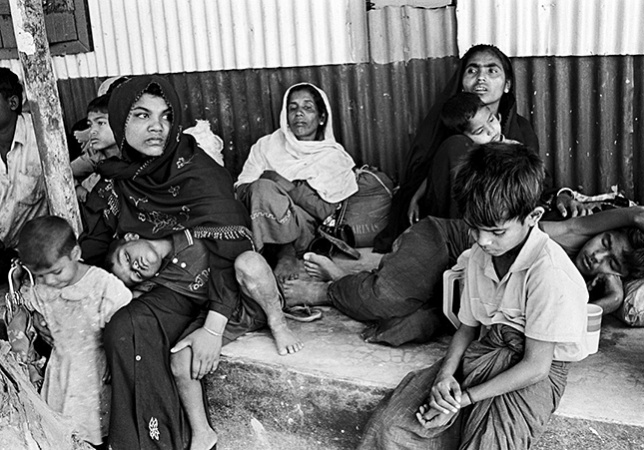

Representatives of 17 countries gathering in Bangkok on 29 May to discuss the humanitarian crisis involving thousands of Rohingya and Bangladeshis adrift in the Andaman Sea must adopt a regional response that complies with international human rights law and standards, said the ICJ today.

“The countries in ASEAN should work with each other and the international community to immediately save the lives of thousands of Rohingya and Bangladeshi people now trapped on ‘floating coffins’, and to address the human rights disaster in Rakhine state that helped create and foster this crisis,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia director.

“It’s essential that the participants of this meeting use this opportunity to establish a response that complies with international law and standards on human rights, the treatment of refugees and migrants, and people in distress on the sea,” he added.

The government of Thailand called the “Special Meeting on Irregular Migration in the Indian Ocean” to provide a forum for countries affected by this crisis.

The main countries involved in this crisis, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Malaysia, have not signed on to the Refugee Convention or to the Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons.

“Now they have to scramble to come up with a sensible and humane response,” Zarifi said.

“ASEAN countries have hidden behind the notion of ‘noninterference’ to turn a blind eye to the persecution of Rohingya in Myanmar, to the growth of criminal smuggling and human trafficking networks, and the increasing demand for undocumented laborers,” he added.

“But this crisis shows that problems in one country can and will quickly spread to the others unless ASEAN can provide a rights-compliant regional response.”

The ICJ calls on all ASEAN Member States and Bangladesh to become parties to key international treaties, such as the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, the Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, and the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR).

The SAR encourages parties to enter into search and rescue agreements with neighboring states to ensure that assistance be provided to any person in distress at sea regardless of the nationality or status of such a person or the circumstances in which that person is found, and provide for their initial medical or other needs, and deliver them to a place of safety.

A draft ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children (ACTIP) and a corresponding Regional Plan of Action (RPA) for the Convention’s operationalization have yet to be endorsed by ASEAN leaders, and no copies of the drafts have been released to the public.

The ICJ calls on ASEAN to make this draft Convention and RPA public and hold consultations with civil society organizations, especially those that work with trafficked persons on which governments so frequently rely as service providers.

The ICJ also points out that certain ASEAN Member States have critical roles to play as integral components to the regional efforts addressing the current crisis.

It is clear that discriminatory policies and actions in Myanmar have significantly contributed to this regional humanitarian crisis, the ICJ says.

The ICJ adds that the Rohingya are forced to flee their homes because of ethnic conflict and the policies of the Myanmar government.

“The government has persecuted the Rohingya, refused to extend basic citizenship rights to them and in fact has recently passed legislation to entrench discrimination against the Rohingya such as the Protection of Race and Religion laws,” said Zarifi.

“These are some of the so-called ‘root causes’ that have displaced thousands within Rakhine State and driven the Rohingya to the sea and to the territory of neighboring countries. It is no longer possible to cite ‘sovereignty’ as an excuse for silencing regional discussions about these serious human rights concerns,” he added.

The ICJ has called on Myanmar to scrap laws that discriminate against minorities and to actively prosecute acts of violence fuelled by discrimination as well as crimes of hate speech.

The ICJ has also urged Myanmar to undertake every effort to improve basic living conditions for the Rohingya and Arrakhanese population in Rakhine State by enhancing respect for and protection of their economic, social, and cultural rights.

The ICJ also called on Thailand to assume its natural role as a key stakeholder in resolving this crisis.

“Thailand’s full commitment to a coordinated regional human rights based response is crucial,” Zarifi further said. “Thailand’s convening of a regional meeting is a welcome step, but as the meeting’s name suggests, Thailand still views this problem as primarily one of migration and trafficking, instead of as a serious human rights crisis that demands a human rights-based regional response.”

Thailand has recently committed to provide humanitarian assistance to migrants and refugees on board the boats.

However, the ICJ emphasized that Thailand and other countries must go further and rescue individuals in distress at sea and allow those who arrive on their shores to expeditiously and safely disembark.

Rather than pushing them back, involuntarily returning them, detaining them or applying other punitive measures, they should be provided with adequate and humane reception conditions and necessary medical care in the country.

Thereafter, with the aid of experts, their further protection and assistance needs must be individually and accurately determined and then addressed, consistent with international standards.

“The Thai government’s response that a naval vessel will be used as a floating administrative center for people already adrift in the waves, and that not even those in need of medical assistance will be allowed onshore, is simply callous and in violation of Thailand’s international obligations,” concluded Zarifi.

Additional information:

Eight ASEAN Member States will be attending the “Special Meeting on Irregular Migration in the Indian Ocean”: Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand. Singapore and Brunei Darussalam are not taking part in the meeting.

Also present will be representatives of Afghanistan, Australia, Bangladesh, India, Iran, New Zealand, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, and Sri Lanka; the United States of America and Switzerland will participate as observers.

Three international organizations, namely the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the UN Office of Drugs and Crimes, and the International Organization of Migration will also join the meeting.

Contact:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Regional Director for Asia and the Pacific, t: +66807819002 ; e: sam.zarifi(a)icj.org

May 4, 2015 | Advocacy, Non-legal submissions

The ICJ welcomes the opportunity offered by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to contribute to its current work on the right to just and favourable conditions of work.

Like other UN treaty bodies, the Committee elaborates general comments to interpret the treaty it is in charge of monitoring and to provide guidance on how to implement the provisions and thus comply with the obligations under this treaty.

Currently, the Committee is consulting relevant actors on its further general comment on article 7 of the international Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

This article guarantees a number of rights to individuals at work, including regarding remuneration and occupational health.

The ICJ is particularly pleased to be given the possibility to share its international and country-based experience on the very topical issues covered by article 7.

In addition to its written submission (read below), the organization will actively participate in the further consultation that will take place during the Committee’s next session in June.

Universal-CESCR Draft General Comment Article 7-Advocacy-Non legal submission-2015-ENG (full text in PDF)

Apr 20, 2015 | News

The ICJ and the Zimbabwe Law Students Association (ZILSA) held a symposium on economic, social and cultural rights (ESC rights) on 17 April 2015 at Rainbow Towers Hotel, Harare.

A total of 84 people attended the symposium, 77 being students from the University of Zimbabwe.

The presenters at the symposium were Deputy Chief Justice L. Malaba, Dr V. Guni, Mr. D. Chimbga, Ms R. Rufu and Mr. J Mavedzenge.

Economic, social and cultural rights are a new phenomenon in Zimbabwe’s human rights discourse as they have been introduced into Zimbabwe’s Declaration of rights by the new Constitution of Zimbabwe (Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.20) Act 2013).

Zimbabwean jurisprudence on ESC rights is therefore still developing.

As a consequence, the notion of the justiciability of ESC rights is one that still requires nurturing if greater protection of these rights is to be achieved.

It was this background that motivated the ICJ and ZILSA to hold this symposium on ESC rights.

The symposium forms part of a broader initiative by the ICJ to ensure ESC rights awareness, education and litigation in Zimbabwe.

Through this symposium, the ICJ and ZILSA sought to provide a platform for law students to engage in an academic discussion on the scope, meaning and enforcement of the ESC rights.

The symposium discussions were meant to increase the students’ knowledge and understanding of ESC rights.

The topics presented at the symposium focused on the historical development and significance of ESC rights, litigation and justiciability of ESC rights under the new constitution and international best practices in the implementation of ESC rights.

The key note address was made by Deputy Chief Justice Malaba, under the topic, “Defining the Role of the Judiciary in the Enforcement of ESC Rights in Zimbabwe”.

The focus of his presentation was how the Zimbabwean judiciary has developed jurisprudence around ESC rights and in particular the approach of the Constitutional Court to the issue of “progressive realization” of ESC rights.

Commenting, after the symposium, Herbert Muromba a 4th year law student and President of ZILSA said: “The Deputy Chief Justice has transformed my understanding of ESC rights. The whole concept is no longer abstract but real, alive and relevant in my everyday life.”

Contact:

Arnold Tsunga, ICJ Regional Director for Africa, t: +27 73 131 8411, e: arnold.tsunga(a)icj.org