Mar 23, 2022 | Advocacy, Non-legal submissions

The ICJ today drew the attention of the UN Human Rights Council to the lack of respect, protection and fulfilment of the freedom of expression, assembly and association and to the widespread discrimination of LGBTI persons during the discussion on the outcome of the UPR of Eswatini.

May 17, 2021 | News

LGBTI people in Indonesia, particularly trans women, face significant discrimination in access to Covid-19 vaccines as the country rolls out its vaccination programme in the face of a surge in the pandemic, the ICJ said today.

Indonesia is planning to start vaccinating the general population in July and an electronic identity card (e-KTP) is required to be vaccinated. However, most trans women do not have, or cannot obtain, an e-KTP and are thus unable to access the COVID-19 vaccines.

“As we mark the International Day against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia on 17 May, Indonesian authorities must ensure that LGBTI communities, trans women in particular, are not excluded from access to vaccines,” said Ruth Panjaitan, ICJ Legal Adviser for Indonesia.

To get an ID card, trans women need to present a Family Card, a document issued to the head of the family. However, many, trans women or waria have been kicked out of or fled their family homes without formal documents as a result of domestic violence. Between 50-60% of transwomen senior citizens reportedly do not have e-KTP, which makes it difficult for them to access government’s healthcare service, including COVID-19 vaccination.

“Most waria in Indonesia don’t even have an ID card let alone an e-KTP. The current system compounds the discrimination against trans women with the heightened risk of illness due to Covid-19. Indonesian authorities must urgently reform the e-KTP system to facilitate the legal status of people based on their own self-identified gender identity,” Ruth Panjaitan said.

Trans women who want to process their e-KTP in accordance with their gender identity have to first obtain an affirmation of their gender from a court, as the e-KTP does not recognize transgender. There is currently no definite and clear regulation for the legal gender change under Indonesia’s law or Supreme Court regulations, so the determination will depend on individual judges in each court’s jurisdiction. LGBTI activists have noted that in practice many judges apply arbitrary religious-based criteria to reject the petition to change gender. In most cases, the court that takes on the application still requires a doctor’s medical certificate that the petitioner has conducted gender reassignment surgery or other hormonal treatment as well other onerous document requirements, such as a psychiatric evaluation and witness information.

“These intrusive, arbitrary, prolonged and burdensome procedures make it even more difficult for trans women in Indonesia to get legal recognition of their gender identity, and lack of recognition of gender identity before the law blocks their access to health care,” Ruth Panjaitan said.

The Indonesian authorities have recently started their effort to reach out to transgender people in order for them to be registered in accordance with Law No.24 year 2013 and Law No.23 year 2006 regarding Civil Administration, which mentions that all Indonesian citizens have to be registered and that they have to have both ID and Family Card, so that they can get a good public service. However, the current system still falls short under international law to protect transgender people.

“Excluding and marginalizing trans women in the middle of a pandemic aggravates the longstanding discrimination they have faced from the Indonesian government, and it is also counterproductive to an effort to vaccinate as many people as possible to stop the spread of the disease,” Ruth Panjaitan said.

Additional information

Transgender people in Indonesia have a right to nondiscriminatory access to vaccines and overall rights to health, which is protected under Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) to which Indonesia is party. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has affirmed that all healthcare goods, facilities, and services must be available, accessible, acceptable and of adequate quality, especially to the most vulnerable or marginalized sections of the population, in law and in fact, without discrimination of any of the prohibited grounds.

Under international human rights law and standards, a person’s declaration of their preferred gender identity for the purpose of obtaining gender recognition should not require validation by a medical expert, judge or any other third party. Requiring someone seeking legal recognition of their self-identified gender to undergo treatment is a breach of their right to protection against attacks on their dignity and physical and mental integrity, guaranteed under the ICESCR and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Indonesia is a party.

As affirmed by the Yogyakarta Principles, which address the human rights of LGBTI persons, gender identity is a private matter, concerning someone’s deeply felt individual conviction, which should not be subject to arbitrary third-party scrutiny. Legal gender recognition processes protecting the rights of transgender people must be conducted without medical requirements and it must be quick, transparent, and accessible, and effectively uphold the rights of transgender people, including their right to self-determination.

As of 10 May 2021, Indonesia has reported more than 5,000 new infections on average each day and 1,718,575 cumulative confirmed COVID-19 cases. The figure brought the country to the fourth position of countries with highest cases in Asia. The inoculation programme kicked off in mid-January for those deemed to be high priority, such as health workers, the police and military, and other public workers. The proportion of Indonesia’s total population that has received at least one dose of a vaccine as at 4 May 2021 was 4.64 per cent.

Contact

Ruth Panjaitan, Legal Adviser for Indonesia, e: ruthstephani.panjaitan(a)icj.org

Download

Press Release in Bahasa Indonesia.

Apr 1, 2021

An opinion piece by Mathuri Thamilmaran, ICJ National Legal Adviser in Sri Lanka.

On 1 March 2021, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa elicited considerable public interest through a single tweet. In his tweet commemorating Zero Discrimination Day, he declared his intent to ‘secure everybody’s right to live life with dignity regardless of age, gender, sexuality, race, physical appearance and beliefs’.[1]

According to reports, the tweet made history as the first public acknowledgment by a South Asian Head of State of everyone’s right not to be discriminated against on the basis of sexuality and gender, thus affirming, effectively, one’s right to live life with dignity regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity or expression. It comes at a time when the President has initiated the drafting process of a new Constitution and a first draft is expected soon.

The tweet has opened up a much-needed conversation on sexual orientation, gender identity and expression (SOGIE) in Sri Lanka, particularly regarding the Government’s obligation to ensure that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people are not discriminated against in law or practice.

As it stands, the Sri Lankan Constitution guarantees the right to equality before the law and equal protection of the law of all persons (Article 12). It also prohibits discrimination on the grounds of race, religion, language, caste, sex, political opinion and place of birth.

Notably, therefore, the Constitution does not prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity and/or expression.

Sections 365 and 365A of Sri Lanka’s Penal Code (1883) criminalize “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” and “acts of gross indecency”, respectively. Both sections have been used to criminalize consensual same-sex sexual relations, albeit the Penal Code does not provide a definition of the terms used by those sections. Those convicted of the ‘crime’ may face up to ten years’ imprisonment.

Section 399 of the Penal Code criminalizes “gender impersonation”, and has often been used against transgender persons with cases being filed against them “for misleading the public”. Further, the loitering provisions of the Vagrants Ordinance (1842) have been used to intimidate, extort, detain and interrogate individuals whose appearance do not conform to gender norms.

In addition, Article 16 of the Constitution states that ‘existing written law and unwritten law shall be valid and operative notwithstanding any inconsistency’ with the provisions of the Fundamental Rights chapter.

As a result, judicial review of existing laws, such as the Penal Code and Vagrants Ordinance, is precluded, thereby shielding the authorities from any scrutiny, including in cases that have given rise to abuse allegations. These provisions have all contributed to an increase in human rights violations by police officers against LGBT persons.

Just last year, a special investigation by a local newspaper found that inhumane methods, including flogging and anal/vaginal examinations, which amount to torture or other ill-treatment, were being used against LGBT people by Sri Lankan authorities to obtain “evidence” of same-sex sexual relations. There had also been instances where H.I.V. tests had been ordered by courts and their results publicly revealed in court, a clear violation of the right to privacy of the individuals concerned.

Following these revelations, the Minister of Justice, Hon. Ali Sabry, made an official statement that he had instructed the relevant authorities to stop such harmful practices while also reiterating his belief in non-discrimination on the basis of ‘gender, sexual preference or identity’. Further, it was reported that as recently as this month, judges were warning the police not to harass transgender persons by misusing the laws and to treat them with dignity.

In 2014, the then Sri Lankan government made representation before the UN Human Rights Committee that Article 12 of the Constitution included non-discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, but, as seen above, explicit provisions and application of the law seem to negate this argument.

Furthermore, in 2017, during its Universal Periodic Review at the Human Rights Council, Sri Lanka committed to taking steps to end discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Since then, however, attempts to include SOGIE in the National Action Plan on Human Rights have been dropped due to opposition within the Cabinet.

Sri Lanka’s neighbours in South Asia have made progressive strides, with both India and Bhutan having decriminalized consensual same-sex sexual relations in recent years. Bhutan’s penal code provision regarding ‘sex against the order of nature’ had been enacted only in 2004 but activism and the recognition that the law would dissuade those in same–sex relations from actively seeking treatment for H.I.V. led to the decision to decriminalize.

In 2018, the Indian Supreme Court read down section 377 of the Indian penal code which was used to criminalize consensual same-sex sexual relations, and stated that its application to consensual relations between LGBT persons was unconstitutional as it was in violation of certain fundamental rights, including the right to equality.

In 2018, Pakistan enacted a law recognizing the human rights of transgender people, including the right to legal recognition of one’s preferred gender identity. Among other things, the understanding that most of the discriminatory legal provisions were remnants of British colonial rule and the need to move past such influence has led to these developments.

In Sri Lanka, homophobia is primarily seen as cultural issue, but there are indications that times are changing. Sections of the media now allow more space for discussions of LGBT persons’ human rights, even covering Pride events, while a Supreme Court judgment in 2016 noted that ‘consensual sex between adults should not be policed by the state nor should it be grounds for criminalisation’.

If a discriminatory law passed as late as 2004 can be discarded by Bhutan, then surely Sri Lanka too can follow its neighbours and break free from its colonial era shackles and guarantee equality for LGBT persons.

It is time that Sri Lanka steps up to fulfil its international human rights obligations by ensuring equality to all persons, including LGBT people, and that it delivers on the expectations raised by the President’s tweet and previous public pronouncements. Last year the President appointed an ‘Expert Committee’ to undertake the drafting of a new Constitution.

The inclusion of SOGIE as prohibited discrimination grounds in the Fundamental Rights protection provided by the (new) Constitution would be a first step in fulfilling the state’s international law commitments as well as rebuilding its relationship with LGBT people.

[1] https://twitter.com/GotabayaR/status/1366258501886955526

SriLanka-SOGI discrimination-News-opeds-2021-TAM (version in Tamil)

SriLanka-SOGI discrimination-News-opeds-2021-SIN (version in Sinhala)

Mar 31, 2021

For International Transgender Day of Visibility, the ICJ launched a report setting out an overview of States’ legal obligations under the international human rights framework in relation to issues of sexual orientation, gender expression and gender identity, and an analysis of the human rights situation of LGBT persons in Colombia, Malaysia and South Africa.

The 60-page report, Invisible, Isolated, and Ignored: Human Rights Abuses Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity/Expression in Colombia, South Africa and Malaysia, was launched through a discussion facilitated by The Cheeky Natives, a literary podcast, with four activists from the three countries on which the report focussed. The activists discussed the content of the report through the lens of their own experience of working with LGBT persons in the respective countries

“As a country, South Africa has possibly one of the most progressive constitutions in the world. It explicitly names sexual orientation. We recognise civil unions; we have a legal gender recognition law. On paper, we are beautiful. In practice, I think we have continuously failed to actualise these rights: access to education, access to healthcare, access to anything that is a general need for every other human being has not been the same for LGBTI people and as marginalised as LGBTI people are in the country, Trans people sit on the margins of that marginalisation,” said Akani Shimange, Director of Matimba, a South African organisation which advocates for kids and teenagers that are transgender or/and gender variant to have happy and healthy lives.

The report aims to offer an overview of different contexts and issues relevant to the respect, protection and promotion of the human rights of LGBT people through a human rights-based analysis and, in so doing, it aims to support lawyers working to enhance protection for the human rights of LGBT persons within their challenging domestic legal frameworks.

“To this day, discrimination and abuse on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity remain rampant around the world. It is important to listen to accounts of LGBT persons who constantly face criminalization, lack of acceptance and continued violence in a climate of impunity exacerbated by the COVID-19 outbreak. This report considers these obstacles, and also makes recommendations to overcome them,” said Sam Zarifi, Secretary General of the ICJ.

The report provides support to the work of LGBT human rights defenders working on human rights issues, as well as assisting policymakers to better understand the impact of law and policy on the human rights of LGBT persons globally.

In addition, the report makes country-specific recommendations to enhance respect, protection and promotion of the human rights of LGBT persons with a view to ameliorating their lives. In Malaysia, where the laws are considerably different from the more progressive Colombian and South African legal frameworks, the recommendations mostly focused around the decriminalization of same-sex consensual conduct and abolition of all laws that criminalize sexual orientation and gender diverse identities as these laws threaten the safety and security of LGBT people and also detrimentally affect the ability of LGBT persons to exercise and enjoy their human rights without discrimination.

As for the Colombian and South African recommendations, the emphasis was on ensuring LGBT persons’ effective access to and enjoyment of existing rights, as well as conducting training programmes on the human rights of LGBT persons based on national and international human rights standards. Additionally, the report calls for programmes to raise awareness about harmful stereotypes, including the use of pejorative language, directed at LGBT persons. In particular, with respect to South Africa, the report documented the limitation on the enjoyment of human rights that have arisen as a consequence of making medical interventions and medical reports mandatory for gender marker change.

Contact

Nokukhanya (Khanyo) Farisè, Legal Adviser (Africa Regional Programme), e: nokukhanya.farise(a)icj.org

Tanveer Jeewa, Legal and Communications Officer (Africa Regional Programme), e: tanveer.jeewa(a)icj.org

Download

Colombia-SouthAfrica-Malaysia-SOGIE-Publications-Reports-Thematic reports-2021-ENG

Nov 19, 2020 | News

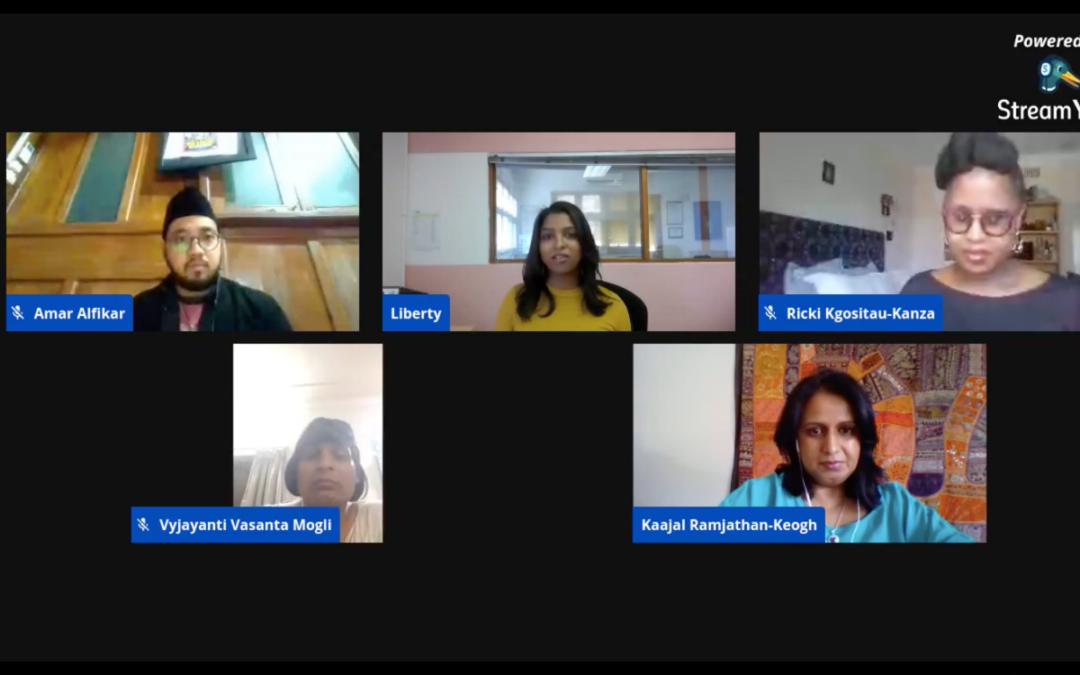

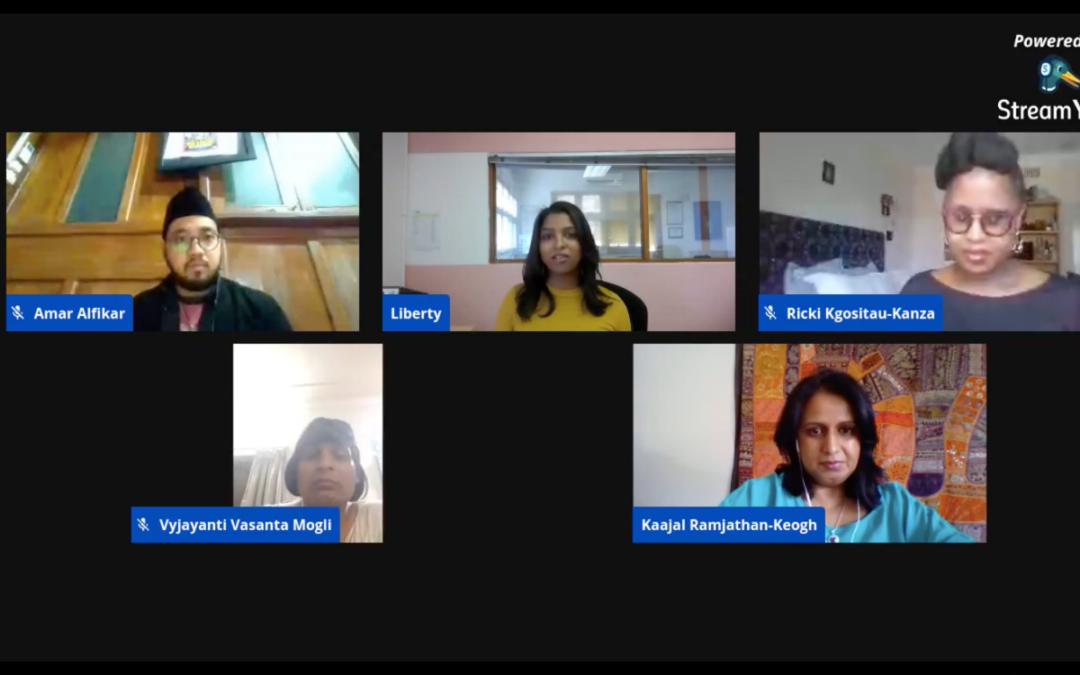

On 18 November 2020, the ICJ hosted a Facebook Live with four transgender human rights activists from Asia and Africa. It highlighted the stark reality between progressive laws and violent lived realities of transgender people.

The 20th November 2020 marks the Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR), the day when transgender and gender diverse people who have lost their lives to hate crime, transphobia and targeted violence are remembered, commemorated and memorialized.

The discussions focused on their individual experiences of Transgender Day of Remembrance in their local contexts, the impact of COVID-19 on transgender communities and whether laws are enough to protect and enforce the human rights of transgender and gender diverse people.

The renowned panelists were from four different countries, Amar Alfikar from Indonesia, Liberty Matthyse from South Africa, Tshepo Ricki Kgositau-Kanza from Botswana and Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli from India. The panel was moderated by the ICJ Africa Regional Director, Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh.

The panel aimed to provide quick glimpses into different regional contexts and a platform for transgender human rights activists’ voices on the meaning of Transgender Day of Remembrance and the varied and devastating impacts of COVID-19 on transgender people.

The speakers discussed the meaning that they individually ascribe to Transgender Day of Remembrance. A common theme running across the conversations was that it is not enough to highlight issues and concerns of the transgender community only on this day. Instead, these discussions should be part of daily conversations about the human rights of transgender people at the local and international level.

Liberty Matthyse discussed the importance of remembering the transgender persons who have lost their lives over the past years, and added:

“South Africa generally is known as a country which has become quite friendly to LGBTI people more broadly and this, of course, stands in stark contradiction to the lived realities of people on the ground as we navigate a society that is excessively violent towards transgender persons and gay people more broadly.”

Amar Alfikar describes his work as “Queering Faiths in Indonesia”. This informs his understanding of what Transgender Day of Remembrance means in his country and he believes that:

“Religion should be a source of humanity and justice. It should be a space where people are safe, not the opposite. When the community and society do not accept queer people, religion should start giving the message, shifting the way of thinking and the way of narrating, to be more accepting, to be more embracing.”

It was clear from the discussions that a lot of the issues that have become prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic, have not arisen due to the pandemic. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has had the effect of a magnifying glass, amplifying existing challenges in the way that transgender communities are treated and driven to margins of society. Speaking about the intersectionality of transgender human rights, Vyjayanti Vasanta Mogli said:

“I don’t think LGBT rights or transgender rights exist in isolation, they are part of a larger gamut of climate change, racial equality, gender equality, the elimination of plastics, and all of that.”

The panelists had different opinions on whether it is enough to rely on the law for the recognition and protection of the human rights of transgender individuals.

The common denominator, however, was that the laws as they stand have a long way to go before fully giving effect to the right of equality before the law and equal protection of the law without discrimination of transgender people.

Tshepo Ricki Kgositau-Kanza, who was a litigant in a landmark case in Botswana in which the judiciary upheld the right of transgender persons to have their gender marker changed on national identity documents, explained the challenges with policies which, on their face, seem uniform:

“Uniform policies… are very violent experiences for transgender persons in a Botswana context where the uniform application of laws and policies is binary and arbitrarily assigned based on one’s sex marker on one’s identity document which reflects them either as male or female. Anybody in between or outside of that kind of dichotomy is often rendered invisible and vulnerable to a system that can easily abuse them.”

This conversation can be viewed here.

Contact

Tanveer Jeewa, Communications Officer, African Regional Programme, e: tanveer.jeewa(a)icj.org