Mar 17, 2021 | News

All children regardless of their age must have access to procedural rights when they are accused of criminal acts, the Council of Europe’s European Committee of Social Rights decided in a landmark case (No. 148/2017) brought by the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) with support from the Prague-based Forum for Human Rights.

The ICJ and Forum lodged a complaint challenging the failure of the Czech Republic to provide for legal assistance to children under the age of 15 (the age of criminal responsibility in the Czech Republic) in the pre-trial stage of proceedings and failure to provide alternatives to formal judicial proceedings for them.

The European Committee of Social Rights, which is responsible for oversight of the European Social Charter of 1961, found the Czech Republic was violating the rights of children under 15, who face proceedings in the child justice system but are below the age of criminal responsibility. The Committee found that the failure to provide these due process safeguards violated the rights of the children to social protection under Article 17 of the 1961 Charter. Human rights protected under the European Social Charter are legally binding on States party to it.

“The Committee’s decision is ground-breaking in many ways, yet two implications are revolutionary. First, it clearly emphasises the inter-dependence between fair-trail rights and child’s well-being. In modern human rights law, there is no such a thing as a clear-cut division between civil and political rights and social rights. But most importantly, the decision undermines paternalistic attitudes towards young children who enter the juvenile justice system and makes clear that all children – regardless their age – must be ensured adequate procedural protection in the course of the whole proceedings, based on the restorative justice principles,” said Maroš Matiaško, senior legal consultant of Forum.

The decision of the European Committee on Social Rights should lead to fundamental changes in the Czech child justice system, Forum for Human Rights and the International Commission of Jurists said today.

“We brought this case to ensure that children below the age of criminal responsibility do not have lower standards of protection of their rights compared to the older children in the child justice system,” said Karolína Babická, ICJ Legal Adviser. “We expect the Czech Republic to swiftly implement the decision of the Committee and ensure that all children regardless their age have access to procedural rights and alternative procedures like settlements and conditional termination or withdrawal of prosecution.”

Background

The legal findings come following a collective complaint submitted to the European Committee on Social Rights by Prague-based Forum for Human Rights and the International Commission of Jurists in 2017.

The Committee’s decision is built on two legal grounds, (I) mandatory legal representation for all children in conflict with the law regardless of age already in the pre-trial stage and (II) their access to alternatives in line with restorative justice principles.

On the first ground, the Committee found that the State must ensure mandatory legal assistance to children below the age of criminal responsibility already in the pre-stage of the proceedings. The reasoning is built on four grounds:

–Children below the age of criminal responsibility are not always able to understand and follow pre-trial proceedings due to their relative immaturity. It cannot therefore be assumed that they are able to defend themselves in this context.

–Children below the age of criminal responsibility should be assisted by a lawyer in order to understand their rights and the procedure applied to them, so as to prepare their defence. The failure to ensure legal assistance for children below the age of criminal responsibility in the pre-trial stage of proceedings is likely to impact negatively on the course of the proceedings, thereby increasing the likelihood of their being subjected to measures such as deprivation of liberty.

–Legal assistance is necessary in order for children to avoid self-incrimination and fundamental to ensure that a child is not compelled to give testimony or to confess or acknowledge guilt.

–The assistance of a lawyer is also necessary in situations where parents/legal guardians have interests that may conflict with those of the child and where it is in the child’s best interest to exclude the parents/legal guardians from being involved in the proceedings. Therefore, the Committee concluded that mandated separate legal representation for children is crucial at the pre-trial stage of proceedings.

In relation to the second legal ground, the Committee emphasised that diversion (alternatives to proceedings, such as settlement or conditional termination or withdrawal of criminal proceedings) from judicial proceedings should be the preferred manner of dealing with children in the majority of cases and diversion options should be available from as early as possible after contact with the system, before a trial commences, and throughout the proceedings. The principle applies to an even greater degree to a situation in which children below that age can still be engaged in the child justice system.

It may be left to the discretion of States Parties to decide on the exact nature and content of diversion measures, and to take the necessary legislative and other measures for their implementation, though there are relevant standards that should be taken into account, especially those developer by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child.

Collective complaints alleging violations of obligations under the European Social Charter, may be brought against States which have ratified the 1995 Additional Protocol to the European Social Charter. On the basis of the European Committee on Social Rights’ decision on a collective complaint, the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers may recommend that the State take specific measures to implement the decision.

Read the full decision here.

See more information about the case here.

Watch our talk on the case and its importance:

Contact:

Karolína Babická, Legal adviser Europe and Central Asia Programme; karolina.babicka(a)icj.org

Feb 16, 2021 | Agendas, Events, News

Today, the ICJ in collaboration with Forum for Human Rights (FORUM) is holding an online training seminar on the rights of children who are suspected or accused of violating the law within the European Union.

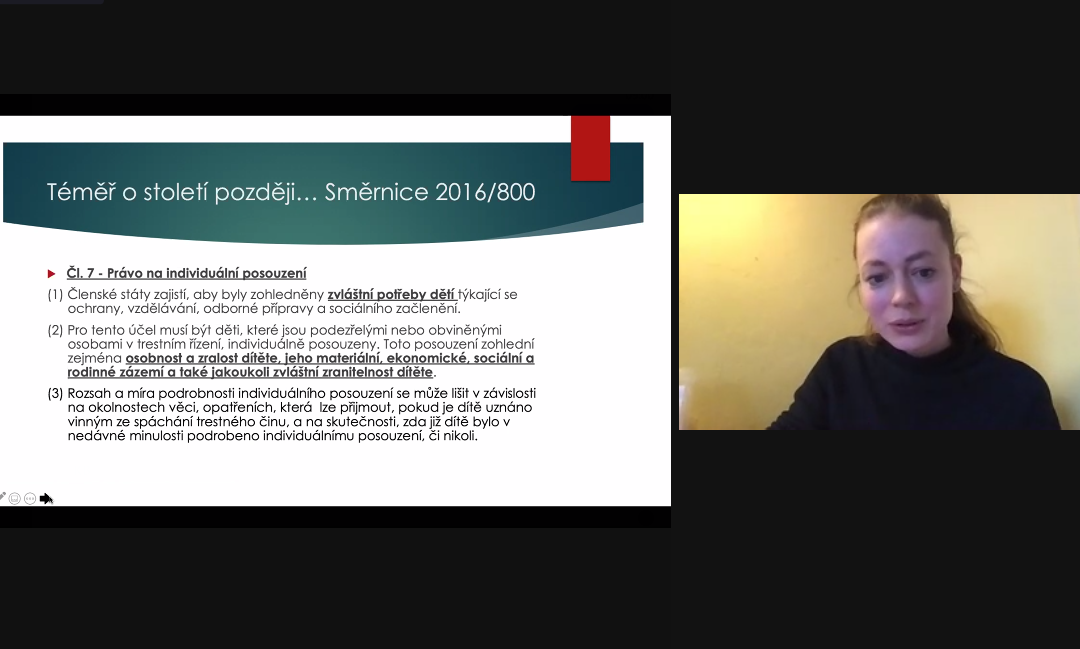

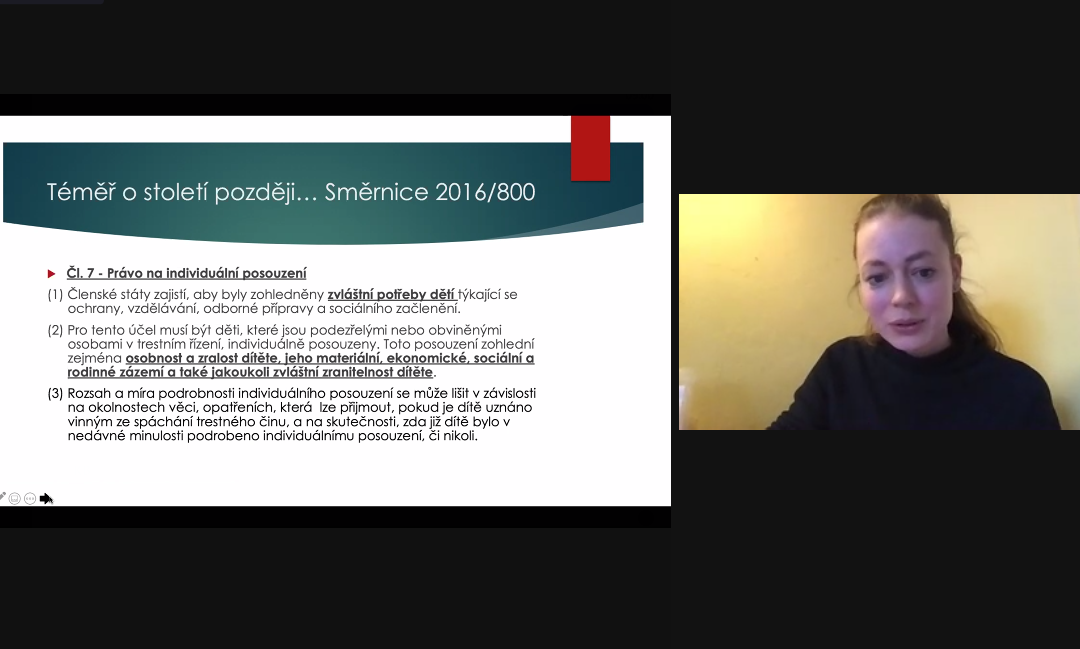

The training (16-18 February 2021) focuses on the right of a child in conflict with the law to an individual assessment, under Article 7 of EU Directive 2016/800 on procedural safeguards for children suspected or accused in criminal proceedings. The individual assessment of the particular circumstances and needs of the child provides an important guarantee which, if implemented through a rights-based approach, can ensure that the best interests of the child are protected and that the child’s rights are upheld throughout the criminal justice process.

The training brings together some of the key professionals involved in implementing individual assessments in the Czech Republic and Slovakia – over 20 lawyers and 20 social workers from both countries working in the field of child justice. Speakers at the training will consider the approach to the individual assessment in light of international human rights law as well as experiences from other EU Member States. They will explore the potential of the restorative justice approach to ensure that the child has practical and effective opportunity to actively participate in the proceedings.

Speakers include Mikiko Otani, ICJ Commissioner and member of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, Dainius Puras, former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, as well as judges and academics other EU Member States and from the European Forum on Restorative Justice, FORUM and ICJ.

See the full agenda here:

in English

in Czech

in Slovak.

This project was funded by the European Union’s Rights, Equality, and Citizenship Programme (2014-2020). The content of this publication represents the views of ICJ only and is its sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

Jun 24, 2019 | News

The ICJ convened a half-day panel discussion today in Yangon, Myanmar, to discuss national laws governing citizenship, and outline how, throughout the country, they have a discriminatory impact on people’s enjoyment of their human rights.

The event also provided the opportunity to introduce the ICJ’s new legal briefing Citizenship and Human Rights in Myanmar: Why Law Reform is Urgent and Possible

ICJ legal researcher Ja Seng Ing and legal adviser Sean Bain kicked off the event by noting that Myanmar’s legal framework for citizenship – enacted by unelected military governments – fuels widespread discrimination against members of ethnic minority groups throughout the country.

Bain highlighted the incompatibility of the domestic legal framework governing citizenship in Myanmar with core rule of law principles and with the State’s obligations under international human rights law, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

He presented the ICJ’s practical recommendations for law reform, outlined in the ICJ’s new legal briefing, including with respect to the 1982 Citizenship Law and the 2008 Constitution, and to the Child Rights Bill currently under consideration by Myanmar’s national parliament.

Senior Advocate U Ohn Maung, a lawyer with decades of experience supporting access for members of minority groups to the official documentation often necessary to obtain even basic services, emphasized that citizenship in Myanmar should be a more inclusive concept, reflective of its pluralistic, multi-ethnic demography.

Daw Zarchi Oo and Daw Su Chit shared the findings of independent civil society research.

They highlighted various groups including: migrants and migrant workers; individuals belonging to sexual and/or gender minorities; single mothers; the children of fathers who are foreign nationals or who are estranged from their fathers; and people living with disabilities, who are all adversely impacted by current legal arrangements for citizenship and by their discriminatory implementation.

Daw Zarchi Oo also spoke about her own past experience of being stateless, and Daw Su Chit elaborated on her work with civil society and others to develop a gendered analysis of the impact of discriminatory citizenship laws in Myanmar.

Around 60 participants, including from domestic civil society, the legal community, international non-government organizations, the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission, the diplomatic community and others joined this event, and participated in the discussions.

The 1982 Citizenship Law embedded the current narrow definition of citizenship, which generally links its acquisition to membership of a prescribed “national race.”

Many of the 2008 Constitution’s provisions on “fundamental rights” are restricted to citizens only, with a result being that the State generally does not recognize the human rights of persons who do not qualify as citizens under domestic law, or are otherwise excluded due to the laws’ discriminatory implementation.

The intentionally discriminatory character of the 1982 Law, and its discriminatory implementation, largely explains why many long-term residents of Myanmar lack a legal identity (more than 25 percent of persons enumerated in the 2014 Census).

The situation of Rohingya people, who the State generally does not recognize as citizens, is the most egregious example of the human rights violations associated with this system.

This event is part of the ICJ’s broader support to promote and protect human rights in Myanmar through research, analysis, advocacy and creating spaces for discussion.

See also:

ICJ convenes workshop on reforming 1982 Citizenship law

Dec 15, 2018 | Events, News

The ICJ convened the 9th annual “Geneva Forum” of Judges and Lawyers in Bangkok, Thailand, 13-14 December 2018, on the topic of indigenous and other traditional or customary justice systems in Asia.

Indigenous and other traditional or customary justice systems play a significant role in many societies around the world, in terms of access to justice for rural communities, indigenous peoples, minorities, and other marginalized populations. At the same time, such systems raise a series of questions in terms of their relationship to international fair trial and rule of law standards, and impacts on human rights including particularly those of women and children.

9th annual Geneva Forum of Judges & Lawyers, 13-14 December 2018, Bangkok, Thailand

Following discussions on these topics at the 2017 ICJ Geneva Forum (an annual global meeting of senior judges, lawyers, prosecutors and other legal and United Nations experts, convened by the ICJ with the support of the Canton and Republic of Geneva (Switzerland) and other partners), the ICJ decided that in order to better engage with customary justice systems, the Geneva Forum would be “on the road” in 2018 and 2019, convening for a regional consultation in the Asia-Pacific in 2018, and in Africa in 2019.

Additional consultations will take place in the Americas. The Forum will return to Geneva for an enlarged session in 2020 to adopt final conclusions and global guidance.

The ninth annual Geneva Forum in Bangkok brought together judges, lawyers, and others engaged with traditional justice systems in the Asia-Pacific region, and practitioners from ordinary justice systems in the region, together with UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples Ms. Victoria Tauli Corpuz, as well as ICJ and UN representatives from Geneva, to discuss and develop practical recommendations, in a private small-group setting.

Participants came from a number of countries across the region, including: Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand and Timor Leste.

The potential and the risks for equal and effective access to justice and human rights

Many participants re-affirmed that traditional and customary justice systems can make an important contribution to improving access to justice for indigenous, and other rural or otherwise marginalized populations, as a result of such factors as geographic proximity, lower cost, lesser cultural or linguistic barriers, and greater trust by local communities, relative to the official justice system.

Indeed, for these and other reasons, for some marginalized and disadvantaged rural populations, traditional and customary courts may in practical terms be the only form of access they have to any kind of justice.

Furthermore, article 34 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples affirms the right of indigenous peoples “have the right to promote, develop and maintain their institutional structures and their distinctive customs, spirituality, traditions, procedures, practices and, in the cases where they exist, juridical systems or customs, in accordance with international human rights standards”.

Furthermore, official recognition of traditional or customary courts in a country can more generally be a positive reflection of the cultural and other human rights of other ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities.

At the same time, the Forum discussions confirmed that, as with formal justice systems, certain characteristics and processes of some traditional and customary justice systems can conflict with international standards on fair trial and the administration of justice, and human rights, particularly of women and children.

Participants in the 2018 Forum discussed a variety of ways in which the relevant communities, their leaders, and decision-makers in indigenous or other traditional systems, together with government authorities, international actors, development agencies, and civil society, can cooperate and coordinate with a view to seeing both formal and traditional systems operate more consistently with international standards on human rights and the rule of law.

There was a range of views on which forms of engagement or intervention were most appropriate or effective. It was also emphasized that work should continue to build the accessibility and capacity of official justice systems to ensure that individuals seeking justice have a real choice.

The above conclusions were subject to the acknowledgement that traditional and customary justice systems take many different forms across the region, and that they exist in many different contexts.

A full report of the Forum discussions will be published by the ICJ in the first part of 2019.

Development of Guidance by the International Commission of Jurists

The ICJ’s global experience and expertise, together with research and global consultations with judges, lawyers and other relevant experts, including the 2017 Geneva Forum, the 2018 session in Bangkok, and subsequent regional consultations in Africa and the Americas, will provide a foundation for the publication by ICJ in 2020 of legal, policy and practical guidance on the role of traditional and customary justice systems in relation to access to justice, human rights and the rule of law.

The ICJ guidance will focus on the mechanisms and procedures of traditional and customary justice systems, as opposed to tackling all aspects of the substantive law.

The guidance will seek to assist all actors involved in implementation and assessment of relevant targets of Sustainable Development Goal 16 on access to justice for all and effective, accountable and inclusive institutions, as well as Goal 5 on gender equality, including: decision-makers and other participants in traditional and customary justice systems; judges, lawyers and prosecutors operating in official justice systems; other government officials; development agencies; United Nations and other inter-governmental organizations; and civil society.

The guidance will be published and disseminated through activities with ICJ’s regional programmes, and its national sections and affiliates, through a series of regional launch events and workshops, as well as at the global level at the United Nations and in other settings.

The guidance will provide the basis for ICJ strategic advocacy at the national level in the years following the conclusion of this initial phase of this work.

Background Materials

Available for download in PDF format:

A Compilation of selected international sources on traditional and customary courts, is available here.

The Final report of the 2018 Geneva Forum, on traditional and customary justice systems, is available here: Universal-Trad-Custom-Justice-GF-2018-Publications-Thematic-reports-2019-ENG

The Final report of the previous, 2017 Geneva Forum, on traditional and customary justice systems, is available here: Universal-Trad Custom Justice Gva Forum-Publications-Thematic reports-2018-ENG

For more information, please contact matt.pollard(a)icj.org.

Jun 12, 2018 | Advocacy, Cases, Legal submissions

The ICJ and others intervened before the European Court of Human Rights in a case of thirteen undocumented children held in a hotspot in Italy.

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), the Dutch Council for Refugees and the AIRE Centre jointly intervened in the case of Trawalli and others v. Italy.

In this case, the European Court of Human Rights is called to rule, among other issues, on whether their detention and reception conditions were lawful and/or constituted an inhuman or degrading treatment under the European Convention on Human Rights.

In their third party intervention, the three human rights organizations submitted the following arguments:

a) Taking into consideration migrant children’s status as persons in situations of vulnerability and the principle of the best interests of the child, article 5 ECHR should be read in light of the rising consensus in international law towards a prohibition of detention of children on immigration grounds, in particular based on the consolidated and clear position of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. This applies to all instances of deprivation of liberty irrespective of their classification under domestic law.

b) In addition to the above, detention under article 5.1 ECHR will in any event be unlawful and arbitrary where it lacks a clear and accessible legal basis, outlining the permissible grounds of detention as well as the relevant procedural guarantees and remedies available to detainees, including judicial review and access to legal advice and assistance. In light of the obligations of EU Member States under EU law, the interveners submit that detention of asylum seeking children falling within the scope of the recast Reception Conditions Directive will result in a breach of the Convention standards also where it is not used as a measure of last resort, but rather is imposed without consideration of less onerous alternative measures and where the child’s best interests assessment has not been carried out and reflected in this decision.

c) Due to children’s extreme vulnerability, their detention for immigration purposes risks leading to a violation of Article 3 ECHR because of inadequate living conditions and/or to a violation of Article 8 ECHR because of a disproportionate and unnecessary interference with their development and personal autonomy, as protected under Article 8. In this sense, Article 8 must be regarded as affording protection from conditions of detention which would not reach the level of severity required to engage Article 3.

d) When the authorities deprive or seek to deprive a child of her or his liberty, they must ensure that he/she effectively benefits from an enhanced set of guarantees in addition to undertaking the diligent assessment of her/his best interest noted above. The guarantees include: prompt identification and appointment of a competent guardian; a child-sensitive due process framework, including the child’s rights to receive information in a child-friendly language, the right to be heard and have her/his views taken into due consideration depending on his/her age and maturity, to have access to justice and to challenge the detention conditions and lawfulness before a judge; free legal assistance and representation, interpretation and translation. The Contracting Parties must also immediately provide the child access to an effective remedy.

e) In order to fully comply with their obligations under the Convention, Contracting Parties must guarantee that asylum seeking children are accommodated in reception facilities which are adapted to their specific needs and provide adequate material conditions adapted to their age, condition of dependency and enhanced vulnerability. To do otherwise results in a failure by States to comply with their obligations under Article 3 ECHR and their specific obligations under EU law.

Italy-icj&others-Trawalli&others-Advocacy-legal submission-2018-ENG (download the intervention)