Jun 15, 2021 | Human Rights Council, News, Work with the UN

To the Permanent Representatives of Member and Observer States of the United Nations Human Rights Council,

Excellencies,

We, the undersigned Lebanese and international organizations, individuals, survivors, and families of the victims are writing to request your support in the establishment of an international, independent, and impartial investigative mission, such as a one-year fact-finding mission, into the Beirut port explosion of August 4, 2020. We urge you to support this initiative by adopting a resolution establishing such a mission at the Human Rights Council.

هذه الرسالة متاحة باللغة العربية أيضاً

On August 4, 2020, one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history decimated the port and damaged over half the city. The Beirut port explosion killed 217 people, including nationals of Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Bangladesh, Philippines, Pakistan, the Netherlands, Canada, Germany, France, Australia, and the United States. It wounded 7,000 people, of whom 150 acquired a physical disability, caused untold psychological harm, and damaged 77,000 apartments, forcibly displacing over 300,000 people. At least three children between the ages of two and 15 lost their lives. Thirty-one children required hospitalization, 1,000 children were injured, and 80,000 children were left without a home. The explosion affected 163 public and private schools and rendered half of Beirut’s healthcare centers nonfunctional, and it impacted 56% of the private businesses in Beirut. According to the World Bank, the explosion caused an estimated US$3.8-4.6 billion in material damage.

The right to life is an inalienable and autonomous right, enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (article 6), which Lebanon ratified in 1972. The Human Rights Committee, which interprets the ICCPR, has stated that states must respect and ensure the right to life against deprivations caused by persons or entities, even if their conduct is not attributable to the state. The Committee further states that the deprivation of life involves an “intentional or otherwise foreseeable and preventable life-terminating harm or injury, caused by an act or omission.” States are required to enact a “protective legal framework which includes criminal prohibitions on all manifestations of violence…that are likely to result in a deprivation of life, such as intentional and negligent homicide.”

The facts as currently known suggest that the storage of more than 2,700 tons of ammonium nitrate alongside other flammable or explosive materials, such as fireworks, in a poorly secured hangar in the middle of a busy commercial and residential area of a densely populated capital city likely created an unreasonable risk to life.

Since the explosion, a number of official documents were leaked to the press, including official correspondence and court documents that indicate customs, port, judicial, and government officials as well as military and security authorities had been warned about the dangerous stockpile of potentially explosive chemicals at the port on multiple occasions since 2013.

Further, the Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 36 on article 6 states: “The duty to protect by law the right to life also requires States parties to organize all State organs and governance structures through which public authority is exercised in a manner consistent with the need to respect and ensure the right to life, including by establishing by law adequate institutions and procedures for preventing deprivation of life, investigating and prosecuting potential cases of unlawful deprivation of life, meting out punishment and providing full reparation.” The investigations into violations of the right to life must be “independent, impartial, prompt, thorough, effective, credible, and transparent,” and they should explore “the legal responsibility of superior officials with regard to violations of the right to life committed by their subordinates.”

The impact and aftermath of the explosion also likely violated Lebanon’s international human rights obligations to guarantee the rights to education and to an adequate standard of living, including the rights to food, housing, health, and property. More notably, Lebanon can only uphold its obligation to provide effective remedy to the victims on the basis of a credible, effective, and impartial investigation whose findings would then be the basis for any effective remedy plan.

In August, 30 UN experts publicly laid out benchmarks, based on international human rights standards, for a credible inquiry into the August 4, 2020, blast at Beirut’s port, noting that it should be “protected from undue influence,” “integrate a gender lens,” “grant victims and their relatives effective access to the investigative process,” and “be given a strong and broad mandate to effectively probe any systemic failures of the Lebanese authorities.”

The domestic investigation into the Beirut blast has failed to meet those international standards. The ten months since the blast have been marked by the authorities’ obstruction, evasion, and delay. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Legal Action Worldwide, Legal Agenda, and the International Commission of Jurists have documented a range of procedural and systemic flaws in the domestic investigation that render it incapable of credibly delivering justice, including flagrant political interference, immunity for high-level political officials, lack of respect for fair trial standards, and due process violations.

Victims of the blast and their relatives have been vocal in calling for an international investigation, expressing their lack of faith in domestic mechanisms. They claim that the steps taken by the Lebanese authorities so far are wholly inadequate as they rely on flawed processes that are neither independent nor impartial. This raises serious concerns regarding the Lebanese authorities’ ability and willingness to guarantee victims’ rights to truth, justice, and remedy, considering the decades-long culture of impunity in the country and the scale of the tragedy.

As we approach the one-year anniversary of the explosion, the case for such an international investigation has only strengthened. The Human Rights Council has the opportunity to assist Lebanon to meet its human rights obligations by conducting an investigative or fact-finding mission into the blast to identify whether conduct by the state caused or contributed to the unlawful deaths, and what steps need to be taken to ensure an effective remedy to victims.

The independent investigative mission should identify human rights violations arising from the Lebanese state’s failure to protect the right to life, in particular whether there were:

- Failures in the obligation to protect the right to life that led to the explosion at Beirut’s port on August 4, 2020, including failures to ensure the safe storage or removal of a large quantity of highly combustible and potentially explosive material;

- Failures in the investigation of the blast that would constitute a violation of the right to remedy pursuant to the rights to life.

The independent investigative mission should report on the human rights violated by the explosion, failures by the Lebanese authorities, and make recommendations to Lebanon and the international community on steps that are needed both to remedy the violations and to ensure that these do not occur in the future.

The Beirut blast was not an isolated or idiosyncratic incident. In the weeks following the explosion, two fires broke out at the port in scenes reminiscent of the fire that resulted in the Beirut blast, terrorizing the public. In February 2021, a German firm tasked with removing tons of hazardous chemicals left in Beirut’s port for decades warned that what they found amounted to “a second Beirut bomb.” If these substances caught fire, Beirut would have been “wiped out”, the interim port chief said.

It is time for the Human Rights Council to step in, heeding the calls of the families of the victims and the Lebanese people for accountability, the rule of law, and protection of human rights. The Beirut blast was a tragedy of historic proportions, arising from failure to protect the most basic of rights – the right to life – and its impact will be felt for far longer than it takes to physically rebuild the city. The truth of what happened on August 4, 2020, is a cornerstone in redressing and rebuilding after the devastation of that day.

The thousands of individuals who have had their lives upended and the hundreds of thousands of individuals who have seen their capital city disfigured in a most irrevocable way deserve nothing less.

List of signatories:

Organizations:

Access Center for Human Rights (Wousoul)

Accountability Now

ALEF – Act for Human Rights

Amnesty International

Anti-Racism Movement

Arab NGO Network for Development

Arab Reform Initiative

Basmeh & Zeitooneh

Baytna

Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

Centre d’accès pour les droits de l’homme (ACHR)

Committee of the Families of the Kidnapped and Disappeared in Lebanon

Dawlaty

Gherbal Initiative

Gulf Centre for Human Rights

Helem

Human Life Foundation for Development and Relief (Yemen)

Human Rights Research League

Human Rights Solidarity (HRS)-Geneva

Human Rights Watch (HRW)

Human Rights Without Frontiers (HRWF)

Impunity Watch

International Commission of Jurists

Justice and Equality for Lebanon

Justice for Lebanon

Khaddit Beirut

Kulluna Irada

Lebanese-Swiss Association

Legal Action Worldwide

Legal Agenda

Liqaa Teshrin

Mada Network

Media Association for Peace (MAP)

Meghterbin Mejtemiin (United Diaspora)

Mwatana for Human Rights

National Youth for Lebanon Movement

PAX (Netherlands)

Peace Track Initiative

Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED)

Refugees=Partners Project

Samir Kassir Foundation

SEEDS for Legal Initiatives

Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression – SCM

The Alternative Press Syndicate Group

The Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief (IHH)

The International Center for Transitional Justice

The Lebanese Center for Human Rights (CLDH)

The Lebanese Diaspora Network (TLDN)

Tunisian League of Human Rights defense (LTDH)

UMAM Documentation & Research

Individuals:

Christophe Abi-Nassif – Lebanon Program Director, Middle East Institute

Nasser Saidi – President Nasser Saidi & Associates; Former Lebanese Minister of Economy & Industry

Randa Slim – Senior Fellow and Director of the Conflict Resolution and Track II Dialogues Program at the Middle East Institute

Survivors and Families of the Victims:

Alexandre Ibrahimcha, lost his mother Marion Hochar Ibrahimcha

Anthony, Chadia, Ava and Uma Naoum

Antoine Kassab, lost his father

Aya Arze Salloum

Carine Farran Sacy

Carine Tohme

Carine Zaatar

Carole Akiki

Cecilia and Pierre Assouad

Cedric el Adm, lost his sister

Charbel Moarbes

Charles Nehme, lost his father

Cybele Asmar lost her aunt Diane Dib

Fouad Rahme, lost his father

Georges Zaarour, lost his brother

Jean-Marc Matta

Jihad Nehme

Joanna Dagher Hayek

Karine Makhlouf, lost her mother

Karine Mattar

Laura Khoury

Lyna Comaty

Mireille el Khoury, lost her son

Myrna Mezher Helou, lost her mother

Nadine Khazen, lost her mother

Nicolas and Vera Fayad

Nicolas Dahan

Olga Kavran

Patrice Cannan, lost his brother

Patricia Haddad, lost her mother

Paul and Tracy Naggear, lost their daughter Alexandra Naggear

Reina Sfeir

Rénié Jreissati

Rima Malek

Rony Mecattaf

Sara Jaafar

Sarah Copland, lost her son Isaac Oehlers

Tania Daou Alam, lost her husband

Tony Najm, lost his mother

Vartan Papazian, lost his daughter-in-law

Vicky Zwein

Zeina Sfeir

Families of the following firefighters:

Charbel Hetty

Charbel Karam

Elie Khouzamy

Joe Akiki

Joe Andoun

Joe bou Saab

Joe Noun

Joseph Merhy

Joseph Roukoz

Misal Hawwa

Najib Hetty

Ralph Mellehy

Ramy Kaaky

Sahar Fares

Contact:

Said Benarbia, Director of the ICJ’s Middle East and North Africa programme, email: said.benarbia@icj.org phone number: +41 79 878 35 46

Asser Khattab, Research and Communications Officer at the ICJ’s Middle East and North Africa programme, email: Asser.khattab(a)icj.org

May 4, 2021 | News

The removal of Lebanese public prosecutor Ghada Aoun from financial cases she had been overseeing constitutes a further attack on the independence of an already enfeebled judiciary, the International Commission of Jurists said today.

On 15 April 2021, Lebanon’s General Prosecutor removed Ghada Aoun, Mount Lebanon Public Prosecutor, from the financial cases she had been overseeing, including high-profile corruption and illegitimate gains cases. Aoun had charged Riad Salameh, the Governor of Lebanon’s Central Bank, with dereliction of duty and breach of trust, and had charged former Prime Minister Najib Mikati with illegitimate gains. She had also been overseeing and issuing arrest warrants in other high-profile cases.

“The Lebanese judiciary has a long history of utter subordination to the ruling political class in Lebanon,” said Said Benarbia, the Director of the ICJ MENA Programme.

“Removing prosecutors and investigating judges from cases solely because they carry out their legitimate functions flies in the face of the independence of the judiciary and sends a chilling message to others who might dare challenging the authorities.”

Aoun’s ouster followed the removal of investigative judge Fadi Sawan from the 2020 Beirut port blast case. Sawan was removed on 18 February 2021 by the Court of Cassation after bringing criminal negligence charges against the acting President of the Cabinet and former ministers in relation to the devastating explosion on 4 August 2020, in which nearly 200 people died and thousands more were injured. His removal by the Court of Cassation came after two former Ministers who were facing criminal charges filed a complaint against Fadi Sawan before the General Prosecutor, requesting his removal from the case.

The Lebanese authorities, including judicial authorities, should comply with their obligations under international law and ensure that judges and prosecutors be able to exercise their functions independently, free of any influences, pressures, threats or interference from any quarter or for any reason.

In August 2020, the ICJ urged the Lebanese authorities to work with the United Nations to establish a special, independent mechanism to probe the Beirut blast in line with international law and standards with a view to establishing the facts and making recommendations for appropriate accountability measures, including criminal prosecutions.

The call was informed by the ICJ publications and findings on the independence and functioning of the judiciary in Lebanon, including recommendations to ensure that the judiciary is not subject to any form of undue influence by political actors and confessional communities, and that it is able to fulfill its responsibility to uphold the rule of law and human rights.

This press release is also available in Arabic.

Contact:

Said Benarbia, Director, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, t: +41-22-979-3817; e: said.benarbia(a)icj.org

Asser Khattab, Research and Communications Officer, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: asser.khattab(a)icj.org

Feb 18, 2021 | Advocacy, News, Publications

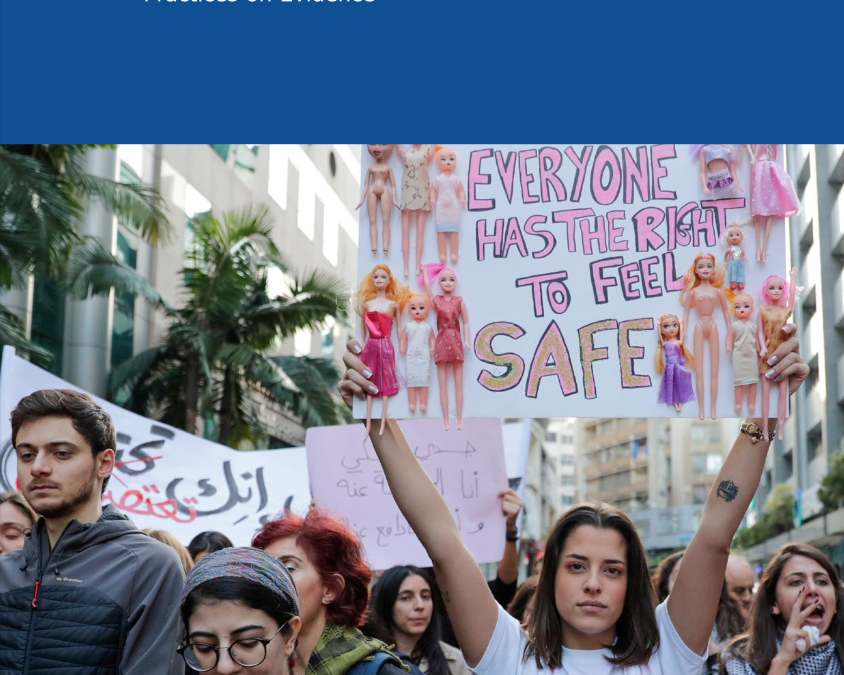

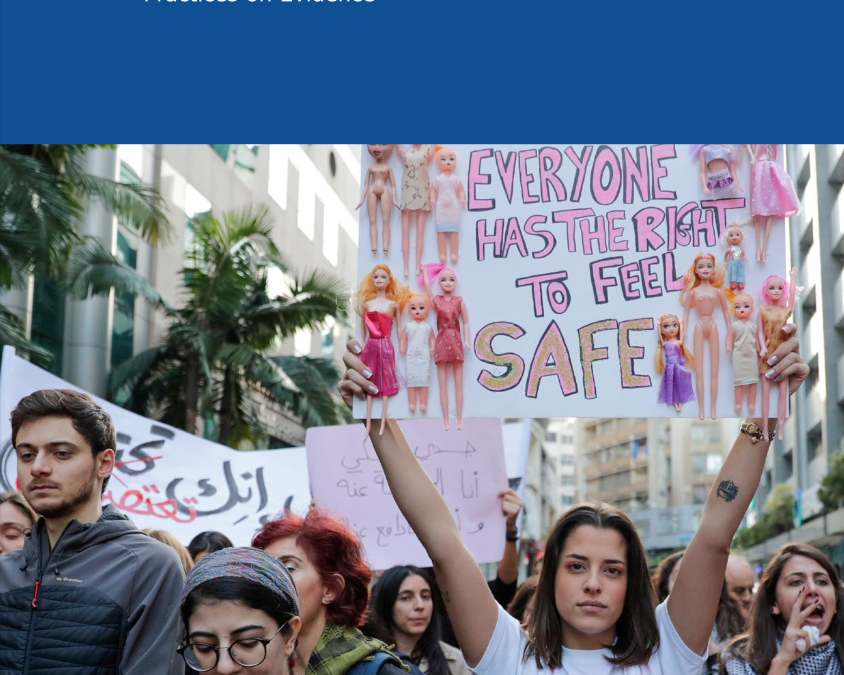

In a memorandum released today, the ICJ published guidance and recommendations aimed at assisting Lebanon’s criminal justice actors in addressing significant gaps in evidentiary rules, practice and procedures undermining the investigation, prosecution and adjudication of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) crimes in the country.

The 42-page memorandum, Sexual and Gender-based Violence Offences in Lebanon: Principles and Recommended Practices on Evidence (available in English and Arabic), aims to advance accountability and justice for SGBV, and is especially designed for investigators, prosecutors, judges and forensic practitioners.

“Criminal justice actors are indispensable to eradicating harmful practices and curbing entrenched impunity for SGBV in Lebanon,” said Said Benarbia, Director of the ICJ’s Middle East and North Africa Programme.

“Rather than buying into false, stereotyped narratives that impugn survivors’ credibility and call into question their sexual history, the criminal justice system must adopt and enforce gender-sensitive, victim-centric evidence-gathering procedures that put the well-being of SGBV survivors at the forefront.”

The memorandum provides criminal justice actors with guidance and recommendations on the identification, gathering, storing, admissibility, exclusion and evaluation of evidence in SGBV cases, as well as on their immediate applicability in practice, pending consolidation and reform of Lebanon’s existing legal framework and procedures for the investigation, prosecution and adjudication of SGBV offences.

“Lebanon’s legal framework fosters and perpetuates a systematic denial of effective legal protection and access to justice for women survivors of SGBV,” said Benarbia. “The justice system must counter harmful gender stereotypes and attitudes rooted in patriarchy, which continue to undermine survivors’ right to effective remedies.”

The memorandum’s release is particularly timely given the escalation of SGBV witnessed since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The memorandum builds on previous research undertaken by the ICJ in this area, including Gender-based violence in Lebanon: Inadequate Framework, Ineffective Remedies and Accountability for Sexual and Gender-based Violence in Lebanon: Guidance and Recommendations for Criminal Justice Actors.

Download

Lebanon-GBV-Memorandum-2021-ENG (Memorandum in English)

Lebanon-GBV-Memorandum-2021-ARA (Memorandum in Arabic)

Lebanon-GBV-Web-Story-2021-ARA (Web story in Arabic)

Lebanon-GBV-Web-Story-2021-ENG (Web story in English)

Contact:

Said Benarbia, Director, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, t: +41-22-979-3817; e: said.benarbia(a)icj.org

Asser Khattab, Research and Communications’ Officer, ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, e: asser.khattab(a)icj.org

Feb 10, 2021 | News

The ICJ and the Lebanese Center for Human Rights (CLDH) are deeply concerned about the role of the military in the arrest, detention and referral for prosecution by military courts of dozens of civilians in Tripoli.

The military’s crackdown has taken place in the context of ongoing protests in the city against a dire economic situation exacerbated by the nation-wide lockdown imposed by the government with the stated intention of combatting the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Under the Rule of Law, the military has no business policing demonstrations, detaining protesters or prosecuting civilians,” said Said Benarbia, the ICJ’s Middle East and North Africa Programme Director. “Instead of addressing the legitimate grievances of those protesting, the Lebanese government is using the military to silence dissenting voices by arresting and sending protestors for trial before military tribunals.”

While the military reported the arrest of five individuals on 27 January, five on 29 January and another 17 on 31 January, for, among other things, allegedly engaging in “rioting,” “vandalism” and “obstruction of civil defence,” other sources suggest at least 58 civilians were arrested by the military in connection with the above-mentioned protests in Tripoli. The whereabouts of many detainees remained undisclosed for days following their arrest. According to lawyers, the military’s Office of Public Prosecution has referred at least 14 individuals to a military Investigating Judge.

The ICJ and CLDH call on the Lebanese authorities to ensure that the military plays no role in policing the ongoing protests and in other law enforcement functions that are properly the sole responsibility of civilian law enforcement agencies. The military courts’ jurisdiction, in particular, must be confined exclusively to the commission of military offences by military personnel and, in turn, totally exclude the possibility of prosecuting civilians, as well as cases involving the perpetration of human rights violations by military personnel.

Referrals by the military’s Office of Public Prosecution follow an increasing, worrying trend of trying those involved in anti-government protests before military courts, which are neither independent nor impartial, and whose procedures do not comply with international fair trial standards.

“Lebanon’s military tribunals have a grim history of unfair trials and politicized proceedings against those suspected of opposing the government,” said Fadel Fakih, CLDH’s Executive Director. “If faith in the Lebanese justice system is to be restored, the jurisdiction of military tribunals must be fully reformed,” he added.

In a 2018 briefing paper entitled “The Jurisdiction and Independence of the Military Courts System in Lebanon in Light of International Standards,” the ICJ called on the Lebanese authorities to enhance the independence and impartiality of military courts, ensure the fairness of their procedures, and restrict their jurisdiction to cases involving members of the military for military offences.

Contact

Said Benarbia, Director of the ICJ Middle East and North Africa Programme, t: +41 22 979 38 17; e: said.benarbia(a)icj.org.

Fadel Fakih, Director of the Lebanese Center for Human Rights, t +961 81 065 041; e: ffakih(a)cldh-lebanon.org

Download

Lebanon-Military-Courts-COVID19-Press-Release-2021-ENG.pdf (English)

Lebanon-Military-Courts-COVID19-Press-Release-2021-ARB.pdf (Arabic)