Nov 30, 2018 | Eventos

La conferencia sobre el tema ‘Las Empresas y los Derechos Humanos en el Departamento de Izabal, Guatemala’ que se llevó a cabo el 29 de noviembre en la Universidad de Ginebra, fue organizada por el Departamento de Derecho Público Internacional y las Organizaciones Internacionales de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de Ginebra en colaboración con la Ciudad de Ginebra.

El evento fue moderado por la Dra. Antonella Angelini del Departamento de Derecho Público Internacional, experta en empresas y derechos humanos. Participaron también Ramon Cadena, Director de la oficina de la CIJ para America Central, Sandra Ratjen, de la Franciscans International, Maynor Alvarez, Director del Departamento de Asuntos Comunitarios de la CGN, Sra. Amalia Caal Coc, de la Fundación Guillermo Toriello, y el Prof. Marco Sassoli, Comisionado de la CIJ.

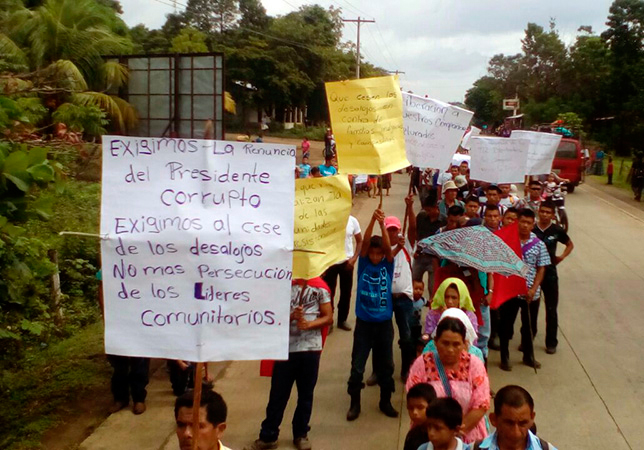

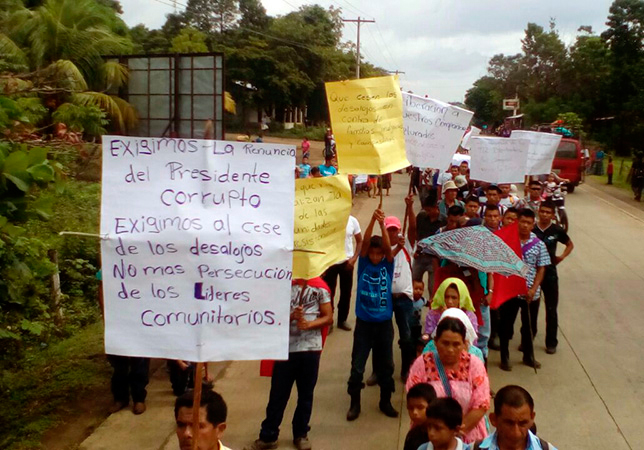

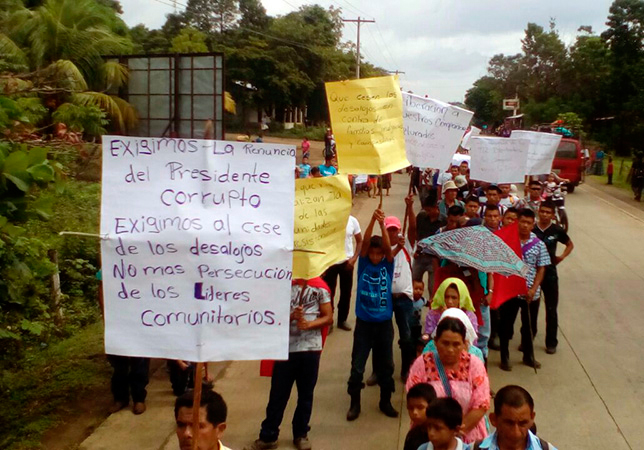

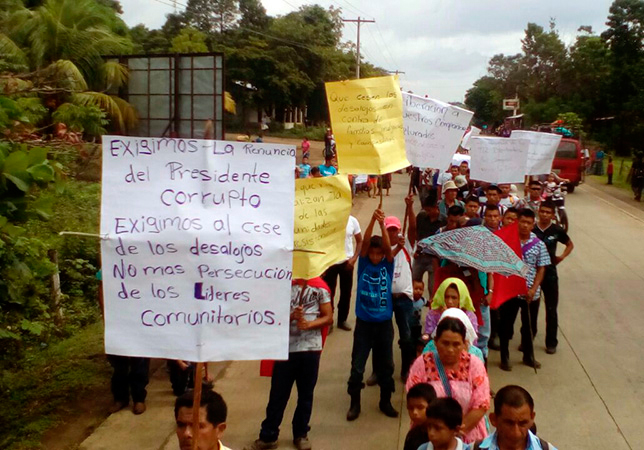

El principal problema discutido fue el impacto sobre las comunidades locales de las operaciones de la Compañía Guatemalteca de Níquel (CGN-PRONICO), una compañía minera de níquel en El Estor, propiedad de Solway Investment Group, compañía registrada en Zug, Suiza.

Ramón Cadena, Director de la oficina de la CIJ para América Central, presentó un resumen de la situación en Guatemala, un país plagado por problemas de corrupción, violencia e impunidad. Enfatizó la necesidad de fortalecer el estado de derecho. Dijo que en el Departamento de Izabal existe mucha preocupación respecto a los impactos de la empresa sobre las comunidades locales de indígenas Q’eqchis. Explicó que estas comunidades no se oponen al desarrollo en sí, pero quieren asegurarse que esta actividad beneficiaría a la mayoría de la población. Concluyó diciendo que la iniciativa popular suiza referente a la responsabilidad social corporativa era sumamente importante ya que implicaría que las multinacionales basadas en Suiza serían responsables de los actos de sus sucursales en otros países.

En sus comentarios finales, el Prof. Marco Sassoli recomendó que se organizara una misión internacional a Izabal en Guatemala con el objetivo de tener una mejor comprensión de los problemas que se presentan a las comunidades locales de Q’eqchis como resultado de las operaciones mineras de níquel de la compañía Solway.

Un informe más detallado sobre la conferencia es disponible acá.

Nov 30, 2018 | Events

The conference on business and human rights in the Department of Izabal, Guatemala was held at the University of Geneva on 29 November 2018 and co-hosted with the Department of Public International Law and International Organization, Faculty of Law of the University of Geneva and the City of Geneva.

The main issue under review was the impact on the local communities of the operations of the Compañia Guatemalteca de Nickel (CGN-ProNico) a nickel mining company in El Estor, wholly owned by Solway Investment Group, a company registered in Zug, Switzerland.

Speaking at the conference, Prof. Marco Sassòli, a Commissioner of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), recommended there be an international mission to Izabal, Guatemala in order to understand the problems facing the local Q’eqchis communities as a result of the Solway nickel mining operations.

Other speakers included Ramon Cadena, the Director of the ICJ Central America office, Amalia Caal Coc, from the Guillermo Torielo Foundation in Izabal, Guatemala, Maynor Alvarez, the manager of the CGN Community Affairs Department, and Sandra Epal Ratjen, Deputb Executive Director at Franciscans International.

Dr Antonella Angelini from the Department of Public International Law and an expert in business and human rights was the conference moderator.

A more detailed account of the conference proceedings is available (download).

Nov 28, 2018 | Events, News

A conference on the situation of business and human rights in Izabal, Guatemala will be held on 29 November 2018 at UNIMAIL University of Geneva at 6:30 pm.

THIS CONFERENCE IS IN FRENCH AND SPANISH ONLY

The conference is co-organised by the International Commission of Jurists, the Department of International Public Law and International Organisation, Faculty of Law, University of Geneva and the Town of Geneva.

Speakers at the conference include Ramon Cadena, the Director of the ICJ Central America Office, Amalia Caal Coc, a local community leader from the Guilermo Torielo Foundation, Maynor Alvarez, Director of Community Relations from the Guatemalan Nickel Company, Solway Group, and Sandra Ratjen, Franciscans International. The panel moderator is Dr Antonella Angelini from the Department of International Public Law and International Organisation.

The meeting room is R070 at UNIMAIL, There will be a discussion after the panel. Entrance is free and there will be interpretation in French and Spanish.

Flyer in Spanish (PDF)

Flyer in French (PDF)

Nov 21, 2018 | Noticias

En el contexto actual de Guatemala, es notorio que el riesgo de abusos de poder y de violaciones a los derechos humanos, ha aumentado significativamente. Esta situación ha hecho surgir graves tensiones entre la Justicia Constitucional, a cargo de la Corte de Constitucionalidad y los poderes Ejecutivo y Legislativo.

Este tipo de tensiones y conflictos se han presentado recientemente, cuando el Tribunal Constitucional ha invalidado actos del Poder Ejecutivo por ser inconstitucionales.

Las y los magistrados de la Corte de Constitucionalidad han demostrado en dichos casos, que pueden emitir resoluciones, sin que se subordinen al Poder Ejecutivo o a otro poder fáctico y velando por la protección de los derechos humanos de todas las personas.

Ramón Cadena, Director de la Comisión Internacional de Juristas expresó que “es necesario reconocer que las y los Magistrados de la Corte de Constitucionalidad, desempeñan una función sumamente difícil, que requiere muy elevadas cualidades judiciales y éticas. Sin embargo, por difícil y compleja que sea su función, cuando el poder público se ejerce con abuso de autoridad y contraviniendo el Derecho Interno y el Derecho Internacional de los Derechos Humanos, la Corte de Constitucionalidad debe fijar los límites que el Derecho Constitucional e Internacional impone al ejercicio del poder.”

Oct 1, 2018 | News

The Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) held a special hearing on the role of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) in Boulder, Colarado.

Ramón Cadena, the ICJ Director stated “We regret that the Government of Guatemala requested the IACHR to hold the hearing behind closed doors since all the points discussed were of public interest. The discussions should have been open to the press and the general public. We urge the authorities to ensure there will be no retaliations against the work carried out by human rights organizations and human rights defenders.”

The ICJ welcomed the participation of many NGOs at the event and the frank dialogue that took place on this crucial issue for human rights in that country. The Guatemalan government delegation claimed that the Inter-American System of Human Rights was not competent to consider the matter. However, the IACHR maintained it was competent, according to the American Convention of Human Rights and other regional human rights legislation. As an “external observer”, the IACHR stated it was “surprised” by the latest decisions taken by government authorities at the highest level not to extend the CICIG mandate nor allow the entry of Commissioner Iván Velásquez into the country. It considered these decisions were “excessive” and in no way strengthened the rule of law in Guatemala.

The government delegation further argued that the CICIG acted as a “parallel prosecutor” which affects the internal order of the country. The NGO delegation stated that on the contrary the CICIG acted as a “complementary prosecutor”. The delegation further noted that before the CICIG mandate was approved, the Constitutional Court, in an opinion published in the official gazette on 8 May 2007 (document no 791-2007), considered that the CICIG did not violate the constitutional order nor the rule of law in Guatemala.

The Constitutional Court referred to the CICIG as having “the function of supporting, assisting and strengthening the state institutions responsible for investigating crimes committed by illegal and clandestine security forces .. and does not exclude the possibility of receiving support from other institutions in the collection of evidence, provided that the participation has been established in a legal manner, as in the present case.”

The IACHR considered that the essential question was whether the State of Guatemala already had the judicial independence and strong institutions necessary to fight against corruption in Guatemala without the support of the CICIG. The NGO delegation considered, based on different arguments, that the presence of the CICIG in Guatemala was still necessary.

The IACHR also informed the government delegation that it was in their interest to invite an in-situ visit of the IACHR as soon as possible so as to better understand the human rights situation.

The ICJ Director for Central America Ramón Cadena participated in the hearing at the request of the Central American Institute for Social Democracy Studies (DEMOS), the Committee for Peasant Development (CODECA) and the Network of Community Defenders. The Indigenous Peoples Law Firm had been requested to attend by these organizations but was unable to do so at the last moment.