Feb 11, 2014 | News

The ICJ condemned the Cambodian Court of Appeal’s decision to deny bail to 21 workers and activists who were arrested in connection with protests by garment factory workers.

They have been held in detention since their arrests on 2 and 3 January 2014.

The court upheld an earlier decision of the Phnom Penh Municipal Court.

Garment factory workers were protesting to seek a higher minimum wage.

“International law is clear that pre-trial detention may only be ordered in exceptional circumstances and avoided if suitable alternatives are possible,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Regional Director for Asia and the Pacific. “The ongoing detention of these protesters, and the failure of the government to provide accountability for the death of five unarmed protesters on 3 January, demonstrates the government’s efforts to stop protesters exercising their rights to assemble freely and express their opinions.”

“Not only is this a very disappointing outcome for the 21 detainees and their families, but it also sets a worrying precedent in what is still a developing area of the law in Cambodia,” he added.

Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Cambodia is a party, guarantees the right to liberty.

It states, “It shall not be the general rule that persons awaiting trial shall be detained in custody, but release may be subject to guarantees to appear for trial.” Such guarantees include bail.

Articles 19 and 21 of the ICCPR guarantee the rights to freedom of opinion and assembly.

Contact:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director, (Bangkok), t:+66 807819002, e-mail: sam.zarifi(a)icj.org

Craig Knowles, ICJ Media & Communications, (Bangkok), t:+66 819077653, e-mail: craig.knowles(a)icj.org

Feb 7, 2014 | News

Bangladesh authorities must immediately cease their harassment of Adilur Rahman Khan, Secretary of Odhikar, a prominent human rights organization and ICJ affiliate, and members of his family, the ICJ said today.

On 5 February 2014, Odhikar reported that two officers of the Special Branch of Police followed a member of Adilur Rahman Khan’s family from his home. When he realized he was being followed he decided to return home. The security officers continued to follow him, and parked their motorcycle next to his house.

Odhikar previously reported that security forces monitor its Dhaka offices as well as Adilur Rahman Khan, his family and other staff. In August 2013, security forces raided Odhikar’s office, confiscating computers containing potentially sensitive material such as the identities of witnesses.

“These actions are deliberate acts of intimidation against Odhikar, its staff and their families, designed to silence the legitimate actions of human rights defenders,” said Ben Schonveld, the ICJ’s Asia Director.

Article 12 of the United Nations Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups, and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (Declaration on Human Rights Defenders), clarifies that States must take all necessary measures to ensure the protection of human rights defenders from any violence, threat, retaliation, pressure, or any other arbitrary action as a consequence of the legitimate exercise of rights, including the freedom of expression.

Background:

Adilur Rahman Khan and Nasiruddin Elan, Secretary and Director of Odhikar, have been charged under section 57 of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act, 2006, for publishing a report on the Government crackdown on a Hefazat-e-Islam rally in May 2013. The report alleged that 61 people were killed in the protest; the Government disputes the number of casualties. Rahman and Khan were indicted on 8 January 2014 and are both currently on bail.

Contact:

Ben Schonveld, ICJ South Asia Director (Kathmandu), t: +977 14432651; email: ben.schonveld(a)icj.org

Reema Omer, ICJ International Legal Advisor (London), t: +447889565691; email: reema.omer(a)icj.org

Jan 10, 2014 | News

The ICJ calls on the Bangladeshi authorities to immediately and unconditionally drop ‘cybercrime’ charges against Nasiruddin Elan and Adilur Rahman Khan, President and Secretary of the human rights group Odhikar.

“These charges are a flagrant attempt to silence critical voices, and the Bangladeshi authorities must immediately and unconditionally drop all charges against the two human rights defenders,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia director.

On 8 January 2014, a cyber crimes tribunal in Dhaka indicted Nasiruddin Elan (picture, on centre) and Adilur Rahman Khan under section 57 (1) and (2) of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act, 2006, for publishing “fake, distorted and defamatory” information. Khan and Elan plead innocent to the charges.

The charges relate to a report by Odhikar that alleged that security forces had killed 61 people during a rally by the Islamist group Hefazat-e Islam in May 2013. The Government disputes the casualty numbers.

The trial is set to begin on 22 January 2014. Under the terms of the newly amended ACT the two human rights defenders face a minimum of seven and maximum of 14 years imprisonment.

“The ICJ has warned that the ICT Act can be used to attack freedom of expression in Bangladesh,” said Sam Zarifi. “As predicted, the Government is now using the newly amended law to silence political and public discourse through the threat of punitive sentences and deliberately vague and overbroad offences in clear violation of international law.”

In a briefing paper released on 20 November 2013, ICJ highlighted that provisions of the 2006 ICT Act (amended 2013), particularly section 57, violate Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Bangladesh ratified on 6 September 2000: the offences prescribed are poorly defined and overbroad; the restrictions imposed on freedom of expression go beyond what is permissible under Article 19(3) of the ICCPR; and the restrictions are not necessary and proportionate to achieve a legitimate purpose.

In addition, the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders underscores that States must take all necessary measures to protect human rights defenders “against any violence, threats, retaliation, de facto or de jure adverse discrimination, pressure or any other arbitrary action as a consequence of his or her legitimate exercise of his or her rights.”

Contact:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director, (Bangkok), t: +66 807819002; email: sam.zarifi(a)icj.org

Ben Schonveld, ICJ South Asia Director, t: +61 422 561834; email: ben.schonveld(a)icj.org

Additional information

Adilur Rahman Khan was arrested his home on 10 August 2013 without an arrest warrant.On August 11, a Magistrate’s Court refused his bail application and remanded him for five days of custodial interrogation.

On August 12, the High Court Division of the Supreme Court stayed the remand order and directed that Adilur Rahman be sent back to jail, where he could be interrogated ‘at the gate of the jail.’

On 4 September 2013, the Detective Branch of Police filed a charge sheet against Adilur Rahman Khan and Odhikar’s Director, Nasiruddin Elan, under Section 57 of the International Communication and Technology Act 2006. On 30 October Adilur Rahman Khan was released on bail. On 6 November 2013, a Dhaka cyber crimes tribunal rejected Nasiruddin Elan’s bail application and ordered his detention in Dhaka Central Jail. Bail was granted on 24 November by the High Court. But the bail order was finally enforced after the appellate division’s order on 3 December 2013.

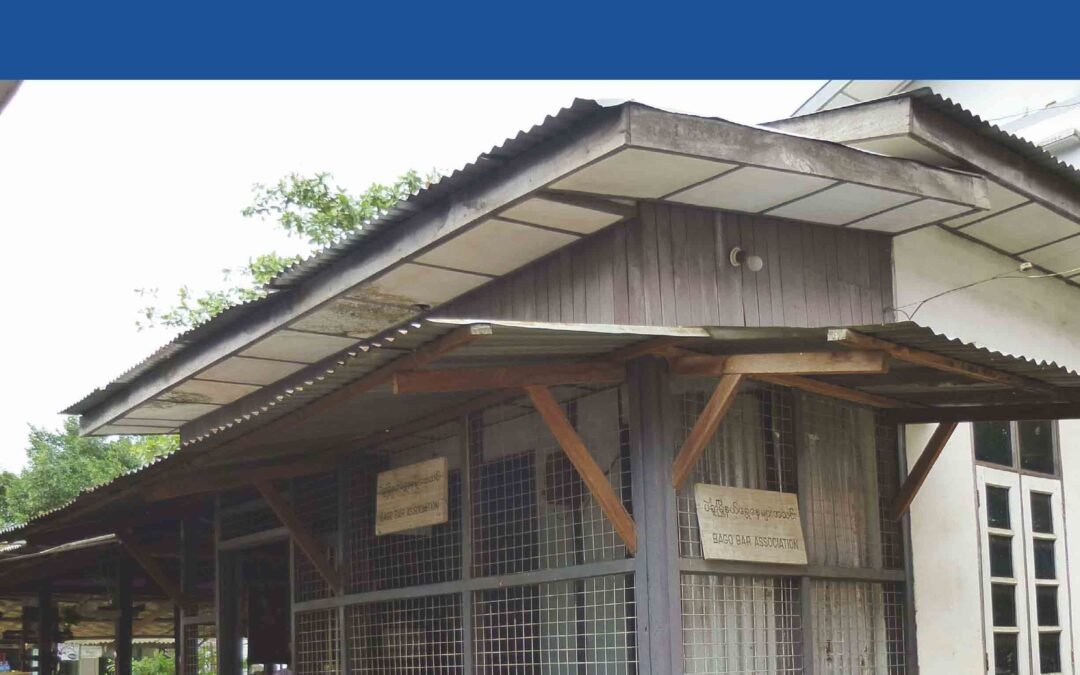

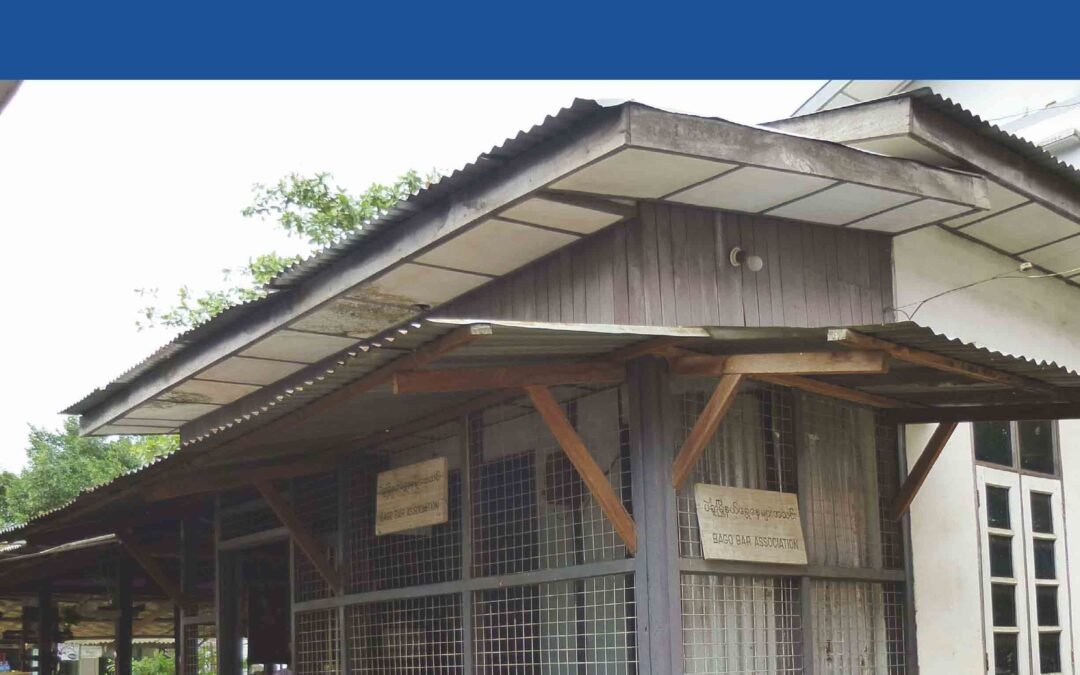

Dec 3, 2013 | News, Publications, Reports, Thematic reports

Lawyers continue to encounter impediments to the exercise of their professional functions and freedom of association, as well as pervasive corruption, although they have been able to act with greater independence, says the ICJ in a new report launched today.

Right to Counsel: The Independence of Lawyers in Myanmar – based on interviews with 60 lawyers in practice in the country – says authorities have significantly decreased their obstruction of, and interference in, legal processes since the country began political reforms in 2011.

“The progress made in terms of freedom of expression and respect for the legal process is very visible,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific director. “But despite the improvements, lawyers still face heavy restrictions and attacks on their independence, which can result in uncertainty and fear, particularly when it comes to politically sensitive issues.”

Systemic corruption continues to affect every aspect of a lawyer’s career and, as a result, is never absent from lawyers’ calculations vis-à-vis legal fees, jurisdictions and overall strategy.

“Corruption is so embedded in the legal system that it is taken for granted,” Zarifi said. “When the public also generally assumes that corruption undermines the legal system, this severely weakens the notion of rule of law.”

“Lawyers in Myanmar, as elsewhere, play an indispensable role in the fair and effective administration of justice,” Zarifi added. “This is essential for the protection of human rights in the country and the establishment of an enabling environment for international cooperation towards investment and development.”

But lawyers in Myanmar lack an independent Bar Council, the report says, noting that the Myanmar Bar Council remains a government-controlled body that fails to adequately protect the interests of lawyers in the country and promote their role in the fair and effective administration of justice.

The ICJ report shows that other multiple long-standing and systemic problems affect the independence of lawyers, including the poor state of legal education and improper interferences on the process of licensing of lawyers.

In its report, which presents a snapshot of the independence of lawyers in private practice in Myanmar in light of international standards and in the context of the country’s rapid and on-going transition, the ICJ makes a series of recommendations:

- The Union Attorney-General and Union Parliament should significantly reform the Bar Council to ensure its independence;

- The Union Attorney-General and Union Parliament should create a specialized, independent mechanism mandated with the prompt and effective criminal investigation of allegations of corruption;

- The Ministry of Education should, in consultation with the legal profession, commit to improving legal education in Myanmar by bolstering standards of admission to law school, law school curricula, and instruction and assessment of students.

Contact:

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Asia-Pacific Regional Director, (Bangkok), t:+66 807819002 e-mail: sam.zarifi(a)icj.org

Craig Knowles, ICJ Media & Communications, (Bangkok), t:+66 819077653, e-mail: knocraig(a)gmail.com

Myanmar-Right to Counsel-publications-report-2013-ENG (download full text in pdf)

MYANMAR-Right to Counsel-Publications-report-2015-BUR (Burmese version in pdf)

Nov 26, 2013 | News

The ICJ is calling on the Malaysian Government to immediately drop the criminal charge against human rights defender Lena Hendry for screening the film ‘No Fire Zone: the Killing Fields of Sri Lanka.’

The case has been fixed for case management and the defence lawyers filed an application to set aside, permanently stay or quash the charges against Lena Hendry.

“Subjecting Lena Hendry to criminal prosecution simply for screening a documentary violates her rights and contravenes Malaysia’s obligations to uphold freedom of expression,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia-Pacific Regional Director.

On 3 July 2013, Pusat Komas, a Malaysian human rights advocacy organization where Lena Hendry works, and Kuala Lumpur and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall Civil Right Committee (KLSCAH CRC) screened the film “No Fire Zone”, a documentary on the war crimes and human rights abuses allegedly committed at the end of the Sri Lankan civil war in 2009.

Immediately following the screening, 30 officers from the Malaysian Ministry of Home Affairs and the police entered the hall and recorded the identity of all persons who attended the event.

The authorities then arrested Lena Hendry and two colleagues, Anna Har and Arul Prakash, and interrogated them for three hours at Dang Wangi police station.

On 19 September 2013, Lena Hendry was charged under section 6(1)(b) of the Film Censorship Act 2002 for showing a film that had not been approved by the Board of Censors.

If found guilty, she could be fined up to RM30,000 (approximately USD 9,322) and sentenced to up to three years imprisonment.

“The Malaysian government told the UN Human Rights Council during its universal periodic review that it maintains a ‘strong commitment to the rule of law, to upholding respect for human rights, and…widening the democratic space”, said Sam Zarifi. “That commitment is inconsistent with prosecuting human rights defenders for disseminating documentary human rights information.”

Under international law and standards, Malaysia must respect the right to freedom of expression of all persons, including the right to seek and impart information of all kinds.

In the case of human rights defenders, the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders imposes a special duty on States not only to respect this right, but also to protect those who exercise this right through their exposure of human rights violations.

The ICJ calls on the Malaysian Government to safeguard freedom of expression and uphold the right of individuals to expose and disseminate information on human rights questions, including the documentation of human rights abuses.