Jan 25, 2019

The ICJ has issued “A primer on international human rights law and standards on the right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief” in which the organization outlines and analyses international human rights law and standards relevant to the right to freedom of religion or belief.

The primer is part of a series of ICJ publications on this theme.

The right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief is a wide-ranging right encompassing a large number of distinct, and yet interrelated entitlements.

International human rights law provides for and guarantees the right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief broadly, encompassing the right to freedom of thought and personal convictions in all matters, and protecting the profession and practice of different kinds of beliefs, whether theistic, non-theistic or atheistic, and the freedom not to disclose one’s religion or belief.

International law also guarantees and protects the right not to have a religious confession.

Among other things, the Primer describes in detail certain key aspects of the right to freedom of religion or belief, including the freedom to adopt, change or renounce a religion or belief; the right to manifest a religion or belief; as well as the relationship between the right to freedom of religion or belief and other human rights, including the principle of non-discrimination, and the right to freedom of expression.

Finally, the primer concludes with a number of recommendations addressed to States in light of its analysis of international human rights law and standards on the right to freedom of religion or belief.

Download

To download the Executive Summary in English, click here.

To download the full primer in English, click here.

To download the full primer in Burmese, click here.

Dec 10, 2018 | Multimedia items, News, Video clips

Today, 10 December 2018 marks the 70th anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Developed as a universal standard setting out the rights to be enjoyed by everyone, the elaboration of the UDHR was one of the first actions undertaken by the newly established UN in carrying out its human rights mandate.

The UN Charter, forged after the ravages of the Second World War, places advancement of human rights as a core purpose and principle of the UN.

Over the past 70 years, the UN and regional human rights systems have taken the UDHR as the benchmark in developing the impressive normative architecture that constitutes the present day basis of international human rights law and standards.

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) was founded in 1952, only four years after the UDHR, with a mission to advance the rule of law and legal protection of human rights. Most of the international legal human framework at that time had still not yet been developed. The founding members of the ICJ believed that the lofty human rights principles enunciated in the UDHR needed to be transformed into hard and enforceable legal obligations incumbent on all States. From its founding, the ICJ worked to develop treaties and other standards aimed to make the enjoyment of human rights real for people, and not merely aspirational.

According to Sam Zarifi, Secretary General of the ICJ, “The ICJ’s biggest contribution to the international legal framework is still to bring together jurists from around the world to defend the rule of law and the universality of human rights at the global and local level.”

“Many now established global legal instruments have the fingerprints of the ICJ all over them. Crucial regional frameworks in the African, European, and American regions were developed with the deep and sustained involvement of the ICJ, as were the creation of the post of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the International Criminal Court,” said Sam Zarifi.

The UDHR has not only inspired the work of human rights defenders, but has also been foundational for the general acceptance of the notion of human rights around the world.

From 1948 until the end of the twentieth century, there has generally been a continuous upward trajectory towards the advancement of human rights, even if there have been many pitfalls along the way.

The notion that people have rights is now universally accepted and known by people. At the Vienna Conference on Human Rights in 1993, all States of the world not only reaffirmed their commitment to the UDHR, but also agreed that “the universal nature of these rights and freedoms is beyond question.”

Over the years, there have certainly been major shortcomings in the push to achieve the realization of the human rights for all.

Some of the extreme examples include armed conflicts replete with crimes against humanity, war crimes and even genocide, followed by a failure to hold perpetrators accountable.

And there remains extreme poverty in parts of the world marked by a thorough neglect of economic and social rights.

Despite these shortfalls in implementation, it remains the case that human rights have been accepted as a key component in addressing humanity’s problems in the 70 years since the adoption of the UDHR.

“Over the years, more and more States have ratified human rights treaties, more States have incorporated human rights in their domestic law, and more courts have started to enforce human rights. At the grass roots law level, more organizations have demanded human rights as an entitlement and not just as an aspiration,” explains Ian Seiderman, Legal and Policy Director of the ICJ.

Despite, this long term trend in advancement of human rights, there are warning signs that progress is slowing and in some places has even reversed particularly in the past decade.

“We are now seeing a very strong pushback against human rights proclaimed in the UDHR from countries around the world,” says Ian Seiderman.

“Some of the pressures have come from the security angle, where even States that previously championed rights insist that rights protection must cede to security interest. More recently there has been a rise in populist authoritarian governments that don’t even pay lip service to human rights anymore. And many States have also turned their backs on the commitment to protect the most marginalized and vulnerable, such as refugees and migrants,” he adds.

Roberta Clarke, Chair of the ICJ Executive Committee:

At the normative level, there remains the notable gap in the international legal protection from transnational corporations and other business that abuse human rights and the reticence of many States to participate in good faith in the efforts at the UN to close this gap with a new business and human rights treaty.

This backlash has only redoubled the ICJ’s commitment to fight for the values originally imagined by the writers of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The ICJ and its individual Commissioners remain heavily involved in the development of human rights standards and their implementation based on the UDHR and a part of the larger human rights movement.

The ICJ continues to work to adopt human rights law to changing conditions in the modern world, develops the human rights capacities of lawyers and judges in all parts of the world, undertakes legal advocacy internationally and in many countries, and provides legal tools for human rights practitioners.

Robert Goldman, ICJ President:

On the 70th anniversary of the UDHR, it is critically important to recall why the UDHR was established in the first place, especially in light of the current regression of human rights development around the world.

The preamble of the UDHR reminds us that “ disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind.”

But more critically, it also insists that addressing these and other acts of inhuman rights require that human rights be protected by the rule of law.

This will be the ICJ’s continuing mission.

Nov 22, 2018

Under its Global Redress and Accountability Initiative, the ICJ has launched its 2018 update to Practitioners’ Guide No 2, outlining the international legal principles governing the right to a remedy and reparation for victims of gross human rights violations and abuses by compiling international jurisprudence on the issues of reparations.

The Guide is aimed at practitioners who may find it useful to have international sources at hand for their legal, advocacy, social or other work.

Amongst revisions to the Guide, the 2018 update includes new sections on terminology and on non-discrimination;updated sections on the notions of ‘collective victims’, ‘collective rights’, the rights of ‘groups of individuals’; additional references to the work of the Committeeon the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and the Committee on the Rights of the Child; an updated section on remedies for unlawful detention, including references to the 2015 UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on Habeas Corpus; and updates on gender-based violence and on violations occurring in the context of business activities.

The Guide first recalls the States’ general duty to respect, protect, ensure and promote human rights, particularly the general duty of the State and the general consequences flowing from gross human rights violations (Chapter 1).

It then defines who is entitled to reparation: victims are, of course, the first beneficiaries of reparations, but other persons also have a right to reparation under certain circumstances (Chapter 2).

The Guide goes on to address the right to an effective remedy, the right to a prompt, thorough, independent and impartial investigation and the right to truth (Chapters 3-4).

It then addresses the consequences of gross human rights violations, i.e. the duty of the State to cease the violation if it is ongoing and to guarantee that no further violations will be committed (Chapter 6). It continues by describing the different aspects of the right to reparation, i.e. the right to restitution, compensation, rehabilitation and satisfaction (Chapter 7).

While the duty to prosecute and punish perpetrators of human rights violations is not necessarily part of the reparation as such, it is so closely linked to the victim’s right to redress and justice that it must be addressed in this Guide (Chapter 8).

Frequent factors of impunity, such as trials in military tribunals, amnesties or comparable measures and statutes of limitations for crimes under international law are also discussed (Chapter 9).

The guide is now also available in Turkish.

Download

Universal-Right to a Remedy-Publications-Reports-Practitioners’ Guides-2018-ENG (full text in English, PDF)

Universal-Right-to-a-Remedy-Publications-Reports-Practitioners-Guides-2018-TR [1] (full text in Turkish, PDF)

Universal-Right-to-a-Remedy-Publications-Reports-Practitioners-Guides-2018-THA (full text in Thai, PDF)

Oct 24, 2018 | News

The ICJ started its 60th anniversary in Geneva with an evening gala hosted by Ambassador Julian Braithwaite, at his residence on 18 October 2018. A moving speech by Sir Nicolas Bratza (photo), ICJ Commissioner and Executive Committee member, on the importance of the defence of the rule of law opened the evening.

It was followed by a magnificent concert by Menuhin Academy virtuoso, violinist Vasyl Zatsikha. A magical evening.

The speech of Sir Nicolas Bratza

“I feel very privileged to have been asked to say a few words by way of introduction to the speech of the Secretary General of the ICJ.

May I begin by expressing on behalf of us all the warmest thanks to the British Ambassador for hosting this very special celebration of the 60th anniversary of the ICJ in its home in Geneva.

Anniversaries are always important occasions and never more so than when they mark a milestone in the life of a remarkable organization that has throughout its existence worked tirelessly to safeguard the rule of law and human rights and that has done so, in particular, by protecting and defending the independence of judges and lawyers.

My association with the ICJ has been relatively brief but for many years I have admired its work from afar, as a member of the European Commission of Human Rights for five years and as a judge of the Strasbourg Court, for fourteen.

The Court and the ICJ share the common purpose – to protect the fundamental principles of democracy, the rule of law and human rights.

Without the independent and impartiality of judges, both national and international, those principles would be meaningless and might as well have been written on water.

With the alarming growth of populism in countries across the world, the threats to the independence of the judiciary are regrettably as real today as they have been at any time.

In the international Court of which I was a member, judges are nominated by the States from which they are drawn.

But they are in no sense representatives of those States and are not infrequently faced with having to decide cases, sometimes cases of acute sensitivity, against their own countries.

The pressures on judges of the Court are often intense and there are notorious examples where the courage shown by a judge in maintaining his or her rigorous independence has come at a cost, the judge being punished by not being renominated by the State, by returning to the country at the end of their mandate without employment or means of livelihood, or by being unable to return safely to their home at all.

But if the position of the international judge is difficult enough, that of the national judge in certain States, including member States of the Council of Europe, is far worse, their independence and security, both physical and professional, being under constant threat.

In the 1990s and in the early years of this century, the signs were promising. One was able to witness a slow but steady improvement in adherence to the rule of law on the part of new democracies.

This was in no small measure due to the work of organizations such as the ICJ which, through its writings, seminars and training of judges and lawyers worldwide, did so much to strengthen and support judicial independence and to expose the most flagrant examples of abuse and undermining of that independence.

I regret to say that in more recent years the landscape has become much darker, with open and insidious attacks on members of the judiciary, the arbitrary removal of judges from their posts and measures taken to curtail the powers of judges and courts or to undermine their authority and independence.

In my official visits to member States as President of the Strasbourg Court, I met several judges who voiced their deep concern about the steps being taken both by the legislature and the executive to compromise their independence and to diminish their authority. It is not only in the new democracies that such a phenomenon has become apparent.

There has been a growing trend in many parts of Europe to undermine the standing and authority of the judiciary by outspoken attacks on judges for unpopular decisions, by members of the executive, by parliamentarians and by the media.

It is these challenges to judicial independence and to the rule of law that make the role of the ICJ and the continued support of the diplomatic community not only more relevant but more vital than they have ever been.

It is with pride and pleasure that I wish the ICJ a very happy anniversary on this its first 60 years of life in this great city.

But I combine this with a fervent hope that, with the support of us all, the ICJ is able to continue its extraordinary work for the next 60 years and far beyond. The protection of the rule of law and human rights depend on it.”

Oct 23, 2018 | Multimedia items, News, Video clips

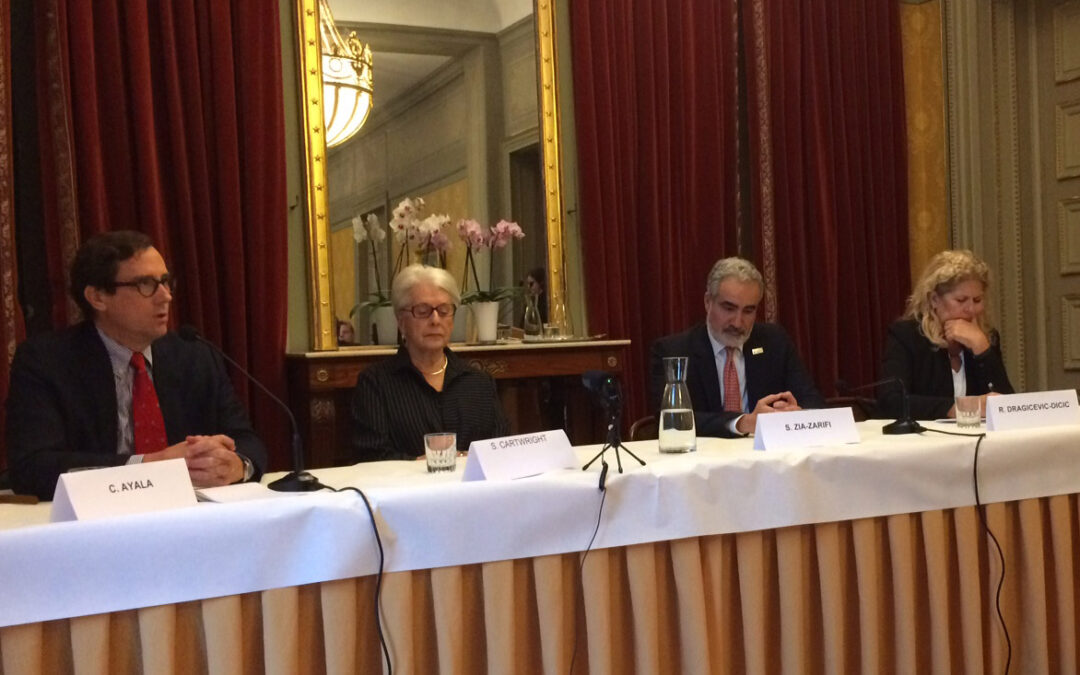

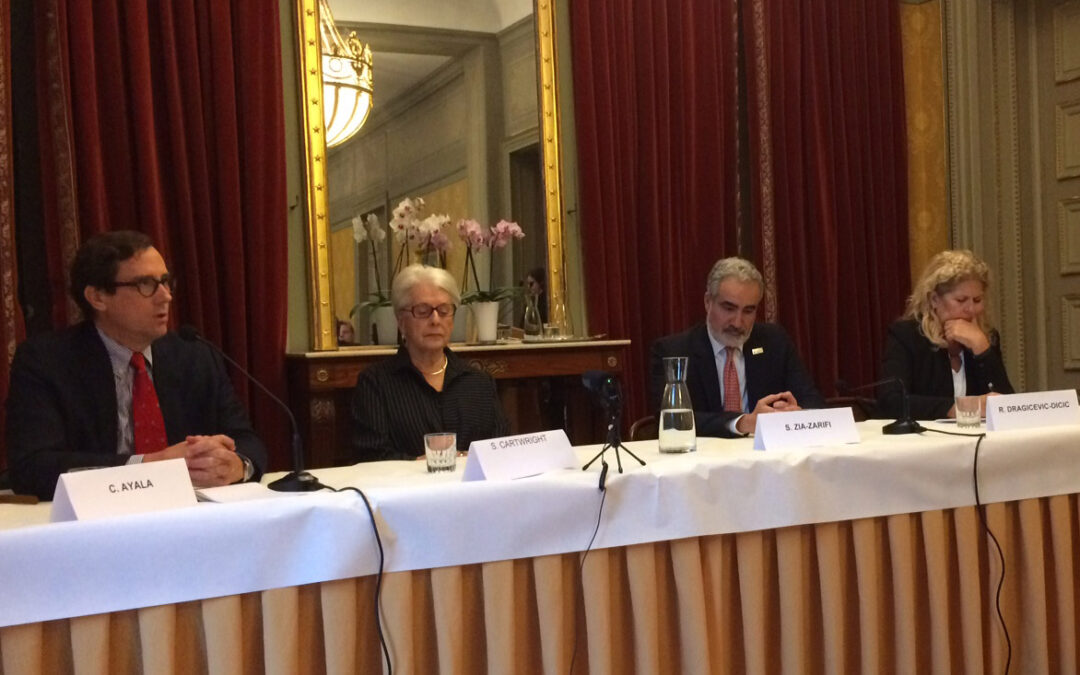

At an event at the city’s Palais Eynard, prominent ICJ Commissioners discussed the supremacy of the Rule of Law and also why it is important to be in Geneva. Watch the video.

The Executive Committee (ExCo), representing the whole Commission of Jurists, participated in the event.

Sam Zarifi, ICJ Secretary General, opened the event by reiterating the importance for the ICJ to be headquartered in Geneva, not only for the UN and international community but also for the city’s and canton’s legal and human rights community.

“It is absolutely clear that we live at a moment in the world when lawyers, judges, jurists are under attack and it is important for the legal community across the world, regardless of borders, regardless of languages, regardless of legal systems, to come together to defend the notion of the rule of law and defend the security and well-being of lawyers and jurists around the world.”

Carlos Ayala, ICJ’s Vice-President, said the ICJ was a unique organization working in the field of the Rule of Law, not as an isolated notion but within the framework of Human Rights and democracy.

He explained how the ICJ is structured and working around the world and insisted on the impact the ICJ is having through its activities.

He said that the organization’s legal outputs were used to have an impact on the overall human rights situations, cases, court decisions, and in training judges, lawyers, prosecutors and others.

Radmila Dragicevic-Dicic, also ICJ’s Vice-President, insisted on how it is important to share experiences about human rights issues and finding solutions to protect different rights.

She gave her personal example of being a judge in former Yugoslavia and Serbia to show how with tenacity and courage one can help establish an independent judiciary even in some of the hardest situations.

She testified how she was helped by the ICJ and Switzerland in her fight for justice.

“If you fight for independence of judges and lawyers in your country, you fight for judges and lawyers everywhere,” she added.

Dame Silvia Cartwright, ICJ Commissioner and ExCo member from New Zealand, was the first woman appointed to the High Court in New Zealand and she was also Governor General of New Zealand.

She said that she was privileged to come from a country that has always promoted and protected the Rule of Law but that unfortunately many recent examples showed that this endorsement could change overnight.

Very active in the fight for women’s rights she said how through her professional work she realized the terrible impact that the Khmer Rouge’s regime in Cambodia and civil war in Sri Lanka had on women.

“Generally speaking I’m quite pessimistic because I think we have reached another stage of the cycle that seems to occur every couple of generations where we are heading towards a more fascist world. So this is the time when human rights must be protected when we must fight to maintain the norms we have struggled for so long,” she said.

Watch the full event here:

https://www.facebook.com/ridhglobal/videos/335212527229422/