Mar 20, 2015 | Advocacy, Non-legal submissions

Today, the ICJ made a submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Myanmar.

The submission brings to the attention of the members of the Human Rights Council’s Working Group issues concerning:

- The independence of the judiciary and legal profession;

- The lack of legislation adequately protecting human rights and the environment;

- Discriminatory laws targeting women and minorities; and,

- The writ of habeas corpus.

Myanmar-UPR-Advocacy-2015-ENG

Mar 3, 2015 | News

Myanmar’s parliament must reject or extensively revise a series of proposed laws that would entrench already widespread discrimination and risk fuelling further violence against religious minorities, Amnesty International and the ICJ said today.

A package of four laws described as aimed to “protect race and religion” – currently being debated in parliament – include provisions that are deeply discriminatory on religious and gender grounds.

They would force people to seek government approval to convert to a different religion or adopt a new religion and impose a series of discriminatory obligations on non-Buddhist men who marry Buddhist women.

“Myanmar’s parliament must reject these grossly discriminatory laws which should never have been tabled in the first place. They play into harmful stereotypes about women and minorities, in particular Muslims, which are often propagated by extremist nationalist groups,” said Richard Bennett, Amnesty International’s Asia-Pacific Director.

“If these drafts become law, they would not only give the state free rein to further discriminate against women and minorities, but could also ignite further ethnic violence,” he added.

The draft laws have been tabled at a time of a disturbing rise in ethnic and religious tensions, as well as ongoing systematic discrimination against women, in Myanmar.

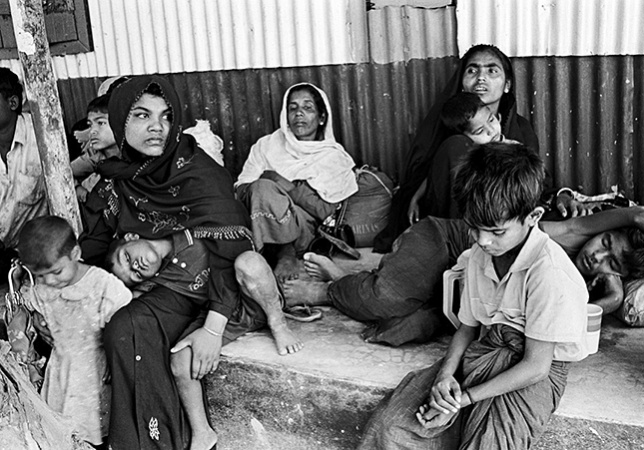

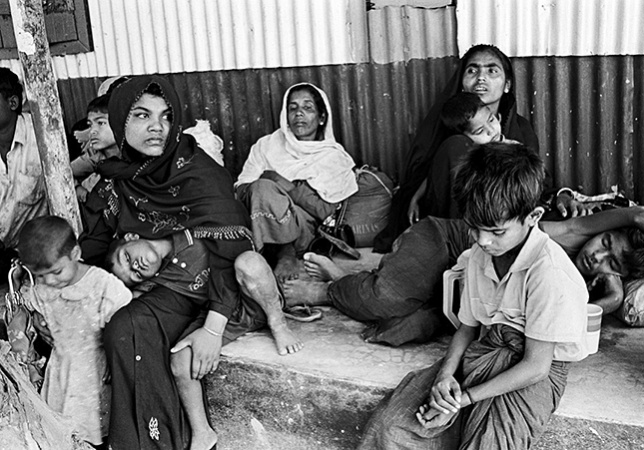

In this context, where minority groups – and in particular the Rohingya (photo) – face severe discrimination in law, policy and practice, the draft laws could be interpreted to target women and specific communities identified on a discriminatory basis.

“The passage of these laws would not only jeopardize the ability of ethnic and religious minorities in Myanmar to exercise their rights, it could be interpreted as signalling government acquiescence, or even assent, to discriminatory actions,” said Sam Zarifi, ICJ’s Asia Director. “The introduction of these discriminatory bills is distracting from the many serious political and economic issues facing Myanmar today.”

Of the four draft laws, two – the Religious Conversion Bill and the Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage Bill – are inherently flawed and should be rejected completely.

The remaining two – the Monogamy Bill and the Population Control Healthcare Bill – need serious revision and the inclusion of adequate safeguards against all forms of discrimination before being considered, let alone adopted.

These bills do not accord with international human rights law and standards, including Myanmar’s legal obligations as a state party to the UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Amnesty International and the ICJ have conducted a legal analysis of the four laws and have found that:

- The Religious Conversion Bill stipulates that anyone who wants to convert to a different faith will have to apply through a state-governed body, in clear violation of the right to choose one’s own religion. It would establish local “Registration Boards”, made up of government officials and community members who would “approve” applications for conversion. It is unclear whether and how the bill applies to non-citizens, in particular the Rohingya minority, who are denied citizenship in Myanmar. Given the alarming rise of religious tensions in Myanmar, authorities could abuse this law and further harass minorities

- The Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage Bill explicitly and exclusively targets and regulates the marriage of Buddhist women with men from another religion. It blatantly discriminates on both religious and gender grounds, and feeds into widespread stereotypes that Buddhist women are “vulnerable” and that their non-Buddhist husbands will seek to forcibly convert them. The bill discriminates against Buddhist women as well as against non-Buddhist men who face significantly more burdens than Buddhist men should they marry a Buddhist woman.

- The Population Control Healthcare Bill – ostensibly aimed at improving living standards among poor communities – lacks human rights safeguards. The bill establishes a 36-month “birth spacing” interval for women between child births, though it is unclear whether or how women who violate the law would be punished. The lack of essential safeguards to protect women who have children more frequently potentially creates an environment that could lead to forced reproductive control methods, such as coerced contraception, forced sterilization or abortion.

- The Monogamy Bill introduces new provisions that could constitute arbitrary interference with one’s privacy and family – including by criminalizing extra-marital relations – instead of clarifying or consolidating existing marriage and family laws.

Contact

In Bangkok – Sam Zarifi, ICJ Regional Director for Asia and the Pacific, sam.zarifi(a)icj.org; m +66807819002

In London – Olof Blomqvist, Amnesty International Asia-Pacific Press Officer, olof.blomqvist(a)amnesty.org; t: +44 20 7413 5871, m +44 790 4397 956

An extensive legal analysis of the laws by Amnesty International and the ICJ can be found here:

Myanmar-Reject discriminatory race and religion draft laws-Advocacy-2015-ENG (full text in PDF)

Feb 9, 2015 | News

Myanmar should continue working with all stakeholders, including affected communities and civil society, to promote a legal framework that balances investors’ needs with human rights, said the ICJ today.

The call comes as the government enters a critical phase of establishing its new law governing investments in the resource-rich country.

“This is a critical moment for the economic development of Myanmar. The laws it implements now will shape investment, economic development and, in turn, human rights for the foreseeable future,” said Daniel Aguirre, ICJ International Legal Advisor. “It is imperative that drafting is not rushed and that laws take into account international human rights laws and standards.”

ICJ has been working directly with Myanmar’s Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (DICA), as well as with Myanmar civil society, on investment law and their potential impact on the human rights of all people in Myanmar.

The International Finance Corporation, in support of DICA, has produced a Draft Investment Law designed to consolidate the Foreign Investment Law (2012) and the Myanmar Citizen Investment Law (2013) to create a level playing field for both local and foreign investors. DICA has now opened the process to civil society consultation.

ICJ conducted a workshop with DICA on bilateral investment treaties in July of 2014. In November, the ICJ submitted feedback on the Draft Investment Law providing expert analysis and flagging issues of concern.

An initial consultation on the Draft Investment Law took place on 29 January 2015. The ICJ along with other civil society organizations met with the IFC and DICA.

“The ICJ is encouraged by DICA’s willingness to consult civil society, including international non-governmental organizations, and hear concerns about investment laws and their potential to curtail important regulations designed to protect, promote and fulfill human rights,” said Aguirre. “The ICJ looks forward to formal engagement in a consultation process that will include both national and international civil society.”

The ICJ remains concerned that the Draft Investment Law establishes significant rights for investors without protecting the rights of those affected by business activity.

The Draft Investment Law would require investors to follow national laws without acknowledging that the existing national legal framework does not adequately protect human rights or provide remedies for those whose rights have been violated.

Furthermore, the Draft Investment Law does not establish or protect Myanmar’s ‘right to regulate’ to protect human rights or other social or environmental needs.

Investment law should indicate Myanmar’s obligation to enact necessary regulations for the protection of human rights, including economic and social rights such as the right to health, in the future in order to avoid legal disputes when adopting these regulations.

“The Draft Investment Law’s proposed legal framework would provide all investors the right to be consulted and challenge any new national law or regulation that may impact their profits,” said Aguirre. “This framework would allow businesses to challenge government policies aimed at addressing legitimate needs within the country, and it could create a regulatory chilling effect in which Myanmar’s government would find itself in the troubling position of evaluating whether the passage of new social policies would lead to costly lawsuits from investors.”

“The draft Law as currently formulated runs the risk of hindering progressive regulation to protect human rights in Myanmar,” said Aguirre. “The ICJ is encouraged that DICA has begun meeting with non-governmental groups and believes that an effective and meaningful consultation will help address key concerns about the Draft Investment Law. The ICJ looks forward to working with the Myanmar Government, with the IFC, and with all other concerned groups in order to promote a law that balances investors’ needs with human rights.”

Feb 5, 2015 | News

Myanmar must follow through on promising efforts to improve the independence and accountability of its legal system, and particularly its judiciary, said the ICJ today at the launch of one of its landmark book in Yangon.

The ICJ launched today the Myanmar language version of its Practitioners’ Guide to the Independence and Accountability of Judges, Lawyers and Prosecutors.

“The judiciary in Myanmar has taken important steps towards asserting its independence from the other branches of government, but we heard repeatedly from the judiciary that they still face significant obstacles in this regard,” said Wilder Tayler, ICJ’s Secretary-General.

The book launch wrapped a series of discussions regarding judicial ethics and the rule of law with the Supreme Court of the Union of Myanmar, as well as with the parliamentary Committee on Rule of Law and Tranquility.

The ICJ’s Practitioners’ Guide n°1 is the first of its kind to be published in the Myanmar language providing detailed references to international and comparative standards on the independence and accountability of judges and lawyers.

“The Supreme Court emphasized its belief that an independent judiciary plays a key role in ensuring access to justice and the protection of human rights, but with independence must come accountability,” Tayler added. “The Myanmar judiciary must be accountable not just in deciding cases according to the law and facts, but also as a separate and equal branch of the government, and ultimately, to the people of Myanmar.”

In the course of its discussions at an earlier workshop in Naypyidaw, the ICJ was repeatedly told that the judiciary is trying to address challenges to its institutional independence, as well as the independence of individual judges.

Corruption, which remains a serious problem throughout all social sectors, including the judiciary, interferes with the judiciary’s ability to provide a remedy for human rights violations and bringing perpetrators to justice.

Undue influence by powerful political and economic actors continues to hamper the push for greater trust and credibility for the judiciary among the general public.

“As we heard at the workshop, at all levels of the system, from the Supreme Court to the Townships, a lack of resources, poor working conditions and low remunerations contribute to an environment where the temptations of corruption, or outside pressure, undermine judicial independence and impartiality,” said Tayler.

“We also heard strong support from all levels of the judiciary for establishing a judicial code of conduct that incorporates international standards and best practices in response to the demands of the people of Myanmar for more rule of law. Producing such a code, and implementing it, would go a long way toward increasing the judiciary’s independence and accountability,” he added.

Wilder Tayler was joined by a senior panel of international legal experts on judicial integrity, including three ICJ Commissioners: Justice Azhar Cachalia of the Supreme Court of Appeals of South Africa, Justice Radmila Dicic of the Supreme Court of Serbia, and retired Justice Ketil Lund of the Supreme Court of Norway.

Feb 3, 2015 | Multimedia items, News, Video clips

On video, ICJ Commissioner Azhar Cachalia and ICJ Asia & Pacific Regional Director Sam Zarifi, talk about a workshop with the Supreme Court of the Union of Myanmar. In parallel with this event, the ICJ met with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

The ICJ’s workshop with the Supreme Court of the Union of Myanmar was on the subject of judicial ethics and the rule of law, while at the meeting with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, discussions covered the ICJ’s focus in Myanmar to support the judiciary in taking important steps towards asserting its independence from other branches of government; and to overcome significant individual and institutional obstacles, such as undue influence by the Executive in politically sensitive and criminal cases, corruption and a lack of resources.

Daw Suu and her colleagues shared information about the Rule of law Centres being initiated as a step towards building the capacity of local legal practitioners and contributing to rule of law reforms in Myanmar.

The ICJ delegation was led by Secretary-General Wilder Tayler, and included Asia & Pacific Regional Director Sam Zarifi, ICJ Commissioners Justices Azhar Cachalia, Ketil Lund and Radmila Dicic, International Legal Advisers Vani Sathisan and Daniel Aguirre and National Legal Adviser Kyawmin San.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is the Chairperson of the Lower House Committee for Rule of Law, Peace and Tranquility in the Myanmar Parliament and Chairperson of the National League for Democracy, and members of her Committee. She was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991.

Justice Azhar Cachalia, ICJ Commissioner and Chair of ICJ’s Executive Committee, talks about his participation in, and contribution to, an ICJ workshop with the Supreme Court of Myanmar.

Sam Zarifi, Director of ICJ’s Asia & Pacific Programme talks about ICJ’s workshop with the Supreme Court of Myanmar